Behavior and Songs of Hybrid Parasitic Finches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species List

Mozambique: Species List Birds Specie Seen Location Common Quail Harlequin Quail Blue Quail Helmeted Guineafowl Crested Guineafowl Fulvous Whistling-Duck White-faced Whistling-Duck White-backed Duck Egyptian Goose Spur-winged Goose Comb Duck African Pygmy-Goose Cape Teal African Black Duck Yellow-billed Duck Cape Shoveler Red-billed Duck Northern Pintail Hottentot Teal Southern Pochard Small Buttonquail Black-rumped Buttonquail Scaly-throated Honeyguide Greater Honeyguide Lesser Honeyguide Pallid Honeyguide Green-backed Honeyguide Wahlberg's Honeyguide Rufous-necked Wryneck Bennett's Woodpecker Reichenow's Woodpecker Golden-tailed Woodpecker Green-backed Woodpecker Cardinal Woodpecker Stierling's Woodpecker Bearded Woodpecker Olive Woodpecker White-eared Barbet Whyte's Barbet Green Barbet Green Tinkerbird Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird Yellow-fronted Tinkerbird Red-fronted Tinkerbird Pied Barbet Black-collared Barbet Brown-breasted Barbet Crested Barbet Red-billed Hornbill Southern Yellow-billed Hornbill Crowned Hornbill African Grey Hornbill Pale-billed Hornbill Trumpeter Hornbill Silvery-cheeked Hornbill Southern Ground-Hornbill Eurasian Hoopoe African Hoopoe Green Woodhoopoe Violet Woodhoopoe Common Scimitar-bill Narina Trogon Bar-tailed Trogon European Roller Lilac-breasted Roller Racket-tailed Roller Rufous-crowned Roller Broad-billed Roller Half-collared Kingfisher Malachite Kingfisher African Pygmy-Kingfisher Grey-headed Kingfisher Woodland Kingfisher Mangrove Kingfisher Brown-hooded Kingfisher Striped Kingfisher Giant Kingfisher Pied -

Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 162 Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species Robert B. Payne Museum of Zoology The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN May 26, 1982 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum techniques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109. MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 162 Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species Robert B. -

The Gambia: a Taste of Africa, November 2017

Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 A Tropical Birding “Chilled” SET DEPARTURE tour The Gambia A Taste of Africa Just Six Hours Away From The UK November 2017 TOUR LEADERS: Alan Davies and Iain Campbell Report by Alan Davies Photos by Iain Campbell Egyptian Plover. The main target for most people on the tour www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 Red-throated Bee-eaters We arrived in the capital of The Gambia, Banjul, early evening just as the light was fading. Our flight in from the UK was delayed so no time for any real birding on this first day of our “Chilled Birding Tour”. Our local guide Tijan and our ground crew met us at the airport. We piled into Tijan’s well used minibus as Little Swifts and Yellow-billed Kites flew above us. A short drive took us to our lovely small boutique hotel complete with pool and lovely private gardens, we were going to enjoy staying here. Having settled in we all met up for a pre-dinner drink in the warmth of an African evening. The food was delicious, and we chatted excitedly about the birds that lay ahead on this nine- day trip to The Gambia, the first time in West Africa for all our guests. At first light we were exploring the gardens of the hotel and enjoying the warmth after leaving the chilly UK behind. Both Red-eyed and Laughing Doves were easy to see and a flash of colour announced the arrival of our first Beautiful Sunbird, this tiny gem certainly lived up to its name! A bird flew in landing in a fig tree and again our jaws dropped, a Yellow-crowned Gonolek what a beauty! Shocking red below, black above with a daffodil yellow crown, we were loving Gambian birds already. -

Rock Firefinch Lagonosticta Sanguinodorsalis and Its Brood Parasite, Jos Plateau Indigobird Vidua Maryae, in Northern Cameroon Michael S

Rock Firefinch Lagonosticta sanguinodorsalis and its brood parasite, Jos Plateau Indigobird Vidua maryae, in northern Cameroon Michael S. L. Mills L’Amarante de roche Lagonosticta sanguinodorsalis et son parasite, le Combassou de Jos Vidua maryae, au nord du Cameroun. L’Amarante de roche Lagonosticta sanguinodorsalis est une espèce extrêmement locale seulement connue avec certitude, avant 2005, des flancs de collines rocheuses et herbeuses au nord du Nigeria. Récemment, plusieurs observations au nord du Cameroun indiquent que sa répartition est plus étendue ; ces observations sont récapitulées ici. Le Combassou de Jos Vidua maryae est un parasite de l’Amarante de roche et était supposé être endémique au Plateau de Jos du Nigeria. L’auteur rapporte une observation de mars 2009 dans le nord du Cameroun de combassous en plumage internuptial, qui imitaient les émissions vocales de l’Amarante de roche. Des sonogrammes de leurs imitations du hôte sont présentés, ainsi que des sonogrammes de cris de l’Amarante de roche. Comme il est peu probable qu’une autre espèce de combassou parasiterait un amarante aussi local, il est supposé que ces oiseaux représentent une population auparavant inconnue du Combassou de Jos dans le nord du Cameroun. ock Firefinch Lagonosticta sanguinodorsalis umbrinodorsalis, but differs from these species R was described only 12 years ago, from the in having a reddish back in the male. The Jos Plateau in northern Nigeria (Payne 1998). combination of a blue-grey bill, reddish back and It belongs to the African/Jameson’s Firefinch grey crown in the male is diagnostic. Uniquely, L. rubricata / rhodopareia clade of firefinches Rock Firefinch was discovered by song mimicry (Payne 2004), and is similar to African Firefinch, of its brood parasite, Jos Plateau Indigobird Vidua Mali Firefinch L. -

Senegal and Gambia

BIRDING AFRICA THE AFRICA SPECIALISTS Senegal and Gambia 2019 Tour Report Vinaceous Black-faced Firefi nch Text by tour leader Michael Mills Photos by Gus Mills SUMMARY ESSENTIAL DETAILS Our first trip to Senegal and Gambia was highly successful and netted a Dates 16 Jan: Full day in the Kedougou area seeing Mali good selection of localised and rarely-seen specials. For this private trip we Firefinch.. ran a flexible itinerary to target a small selection of tricky species. In Senegal 11-23 January 2019 17 Jan: Early departure from Kedougou. Lunch Savile's Bustard was the last African bustard for the entire party, and was at Wassadou Camp. Evening boat trip on Gambia Birding Africa Tour Report Tour Africa Birding seen well both at the Marigots and in the Kaolack area. Other Senegalese Leaders River with Adamawa Turtle Dove and Egyptian Report Tour Africa Birding Plover.. highlights included Western Red-billed Hornbill, Sahel Paradise Whydah Michael Mills assisted by Solomon Jallow in full breeding plumage, Little Grey Woodpecker, Mali Firefinch, Egyptian 18 Jan: Morning at Wassadou Camp, before driving to Gambia. Afternoon around Bansang with Plover and African Finfoot. Large numbers of waterbirds at Djoudj and the Participants Exclamatory Paradise Whydah in full plumage. Marigots were memorable too. Julian Francis and Gus Mills 19 Jan: Early departure from Bansang, driving to Tendaba for lunch via north bank. Afternoon at Tendaba seeing Bronze-winged Courser. Itinerary 20 Jan: Early morning on the Bateling Track seeing 11 Jan: Dakar to St Louis. Afternoon at the Marigots, Yellow Penduline Tit, White-fronted Black Chat, hearing Savile's Bustard. -

GHANA MEGA Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials Th St 29 November to 21 December 2011 (23 Days)

GHANA MEGA Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials th st 29 November to 21 December 2011 (23 days) White-necked Rockfowl by Adam Riley Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader David Hoddinott RBT Ghana Mega Trip Report December 2011 2 Trip Summary Our record breaking trip total of 505 species in 23 days reflects the immense birding potential of this fabulous African nation. Whilst the focus of the tour was certainly the rich assemblage of Upper Guinea specialties, we did not neglect the interesting diversity of mammals. Participants were treated to an astonishing 9 Upper Guinea endemics and an array of near-endemics and rare, elusive, localized and stunning species. These included the secretive and rarely seen White-breasted Guineafowl, Ahanta Francolin, Hartlaub’s Duck, Black Stork, mantling Black Heron, Dwarf Bittern, Bat Hawk, Beaudouin’s Snake Eagle, Congo Serpent Eagle, the scarce Long-tailed Hawk, splendid Fox Kestrel, African Finfoot, Nkulengu Rail, African Crake, Forbes’s Plover, a vagrant American Golden Plover, the mesmerising Egyptian Plover, vagrant Buff-breasted Sandpiper, Four-banded Sandgrouse, Black-collared Lovebird, Great Blue Turaco, Black-throated Coucal, accipiter like Thick- billed and splendid Yellow-throated Cuckoos, Olive and Dusky Long-tailed Cuckoos (amongst 16 cuckoo species!), Fraser’s and Akun Eagle-Owls, Rufous Fishing Owl, Red-chested Owlet, Black- shouldered, Plain and Standard-winged Nightjars, Black Spinetail, Bates’s Swift, Narina Trogon, Blue-bellied Roller, Chocolate-backed and White-bellied Kingfishers, Blue-moustached, -

Manyoni Private Game Reserve (Previously Zululand Rhino Reserve)

Manyoni Private Game Reserve (Previously Zululand Rhino Reserve) Gorgeous Bushshrike by Adam Riley BIRD LIST Prepared by Adam Riley [email protected] • www.rockjumperbirding. -

A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi

A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire 2006 Tauraco Research Report No. 8 Tauraco Press, Liège, Belgium A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire 2006 Tauraco Research Report No. 8 Tauraco Press, Liège, Belgium Tauraco Research Report No. 8 (2006) A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi ISBN 2-87225-003-4 Dépôt légal: D/2006/6838/06 Published April 2006 © F. Dowsett-Lemaire All rights reserved. Published by R.J. Dowsett & F. Lemaire, 12 rue Louis Pasteur, Grivegnée, Liège B-4030, Belgium. Other Tauraco Press publications include: The Birds of Malawi 556 pages, 16 colour plates, 625 species distribution maps, Tauraco Press & Aves (Liège, Belgium) Pbk, April 2006, ISBN 2-87225-004-2, £25 A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire CONTENTS An annotated list and life history of the birds of Nyika National Park, Malawi-Zambia ...........................1-64 Notes supplementary to The Birds of Malawi (2006) ..............65-121 Birds of Nyika National Park 1 Tauraco Research Report 8 (2006) An annotated list and life history of the birds of Nyika National Park, Malawi-Zambia by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire INTRODUCTION The Nyika Plateau is the largest montane complex in south-central Africa, with an area of some 1800 km² above the 1800 m contour – above which montane conditions prevail. The scenery is spectacular, with the upper plateau covered by c. 1000 km² of gently rolling Loudetia-Andropogon grassland, dotted about with small patches of low-canopy forest in hollows. Numerous impeded drainage channels support dambos. These high-altitude Myrica-Hagenia forest patches (at 2250-2450 m) are often no more than 1-2 ha in size, and cover about 2-3% of the central plateau. -

Kruger Comprehensive

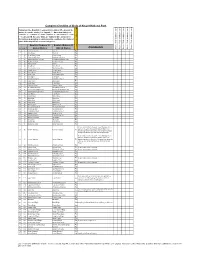

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop -

Song Mimicry and Association of Brood-Parasitic Indigobirds (Vidua) with Dybowski's Twinspot (Eustichospiza Dybowskii)

The Auk 112(3):649-658, 1995 SONG MIMICRY AND ASSOCIATION OF BROOD-PARASITIC INDIGOBIRDS (VIDUA) WITH DYBOWSKI'S TWINSPOT (EUSTICHOSPIZA DYBOWSKII) ROBERT B. PAYNE TMAND LAURA L. PAYNE • •Museumof Zoologyand 2Departmentof Biology,University of Michigan, Ann Arbor,Michigan 48109, USA AI•STRACT.--Apopulation of brood-parasiticCameroon Indigobirds (Viduacamerunensis) in Sierra Leone mimics the songsof its apparent foster species,Dybowski's Twinspot (Eusti- chospizadybowskii). Song mimicry includesthe widespreadsong elementsand phrasesand the major featuresof organizationof song(introductory units, terminal units, repetitionof certain units, and complexity in number of kinds of units in a song) of the twinspots.The songmimicry by indigobirdsof Dybowski'sTwinspots was predictedfrom a hypothesisof the origin of brood-parasiticassociations by colonizationof new foster speciesthat have parentalbehavior and habitatsimilar to their old fosterspecies. Indigobirds (Vidua spp.) now are known to mimic five speciesand generaof estrildidsthat are not firefinches(Lagonosticta spp.), their more commonfoster group. The evolutionarysignificance of songmimicry by indigobird populationsand speciesof severalgenera of estrildid finches,including the twinspot, is that the brood-parasiticindigobirds (Viduaspp.) appear to have associatedwith their fosterspecies through recentcolonizations rather than through ancientcospeciations. Received21 January1994, accepted 2 July 1994. THE AFRICANINDIGOBIRDS (Vidua spp.) are the Viduacospeciated with them and diverged brood-parasiticfinches -

BEHAVIORAL and GENETIC IDENTIFICATION of a HYBRID VIDUA: MATERNAL ORIGIN and MATE CHOICE in a BROOD-PARASITIC FINCH R�G��� B

The Auk 121(1):156–161, 2004 BEHAVIORAL AND GENETIC IDENTIFICATION OF A HYBRID VIDUA: MATERNAL ORIGIN AND MATE CHOICE IN A BROOD-PARASITIC FINCH Rg B. Pf~1,3 i Mh D. Sx2 1Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA; and 2Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachuse s 02215, USA Agxh.—Hybrid male Vidua were observed in the fi eld and recorded to document host song mimicry. The mtDNA of one male was sequenced to identify the maternal parent. The hybrid males mimicked songs of Melba Finch (Pytilia melba), the usual host of Long-tailed Paradise Whydah (V. paradisaea), but the mtDNA matched that of indigobirds (V. chalybeata or another species), which parasitize and mimic other estrildid fi nches. This combination of song behavior and genetics is consistent with a two-generation history that began with a female indigobird (e.g. V. chalybeata) laying in a Melba Finch nest rather than in a nest of her usual host (e.g. Red-billed Firefi nch [Lagonosticta senegala]). Her daughter, genetically an indigobird, imprinted on her Melba Finch foster parents and then mated with a male paradise whydah mimicking Melba Finch song. She also laid eggs in Melba Finch nests. Her son, the male hybrid carrying his grandmother’s indigobird mtDNA, learned and later mimicked Melba Finch song. Genetic identifi cation of the maternal species origin of this hybrid supports a model of mate choice based on mimetic song in the Vidua fi nches. Received 15 February 2003, accepted 5 October 2003. -

Avaliação Rápida Da Biodiversidade Da Região Da Lagoa Carumbo Rapid Biodiversity Assessment of the Carumbo Lagoon Area

REPÚBLICA DE ANGOLA MINISTÉRIO DO AMBIENTE RELATÓRIO SOBRE A EXPEDIÇÃO EXPEDITION REPORT AVALIAÇÃO RÁPIDA DA BIODIVERSIDADE DA REGIÃO DA LAGOA CARUMBO RAPID BIODIVERSITY ASSESSMENT OF THE CARUMBO LAGOON AREA LUNDA NORTE - ANGOLA REPÚBLICA DE ANGOLA MINISTÉRIO DO AMBIENTE RELATÓRIO SOBRE A EXPEDIÇÃO EXPEDITION REPORT AVALIAÇÃO RÁPIDA DA BIODIVERSIDADE DA REGIÃO DA LAGOA CARUMBO RAPID BIODIVERSITY ASSESSMENT OF THE CARUMBO LAGOON AREA LUNDA NORTE - ANGOLA «Há uma centena de anos, uma mulher havia sido «Hundreds of years ago, a woman had been cast expulsa pelo seu povo e andou longe em busca de out by her people, and had wandered far and wide in refúgio. Ela chegou a uma aldeia ribeirinha, Nacarumbo, search of sanctuary. She came upon a riverside village, no belo vale do rio Luxico e implorou por um lugar para Nacarumbo, in the beautiful valley of the Luxico River, ficar. Os moradores perseguiram-na, mas uma família and begged for a place to stay. The villagers chased ofereceu abrigo. Uma noite ela teve uma visão da vinda her away, but one family eventually took her in. One de uma grande inundação e alertou os moradores night she had a vision of the coming of a great flood, para irem para um lugar mais alto, mas nenhum ouviu. and warned the villagers to move to higher ground, Veio o dilúvio, formando a Lagoa Carumbo e afogou but none listened to her. The flood came, forming toda comunidade. Até hoje os sons e conversas da Lagoa Carumbo, and drowning the whole community. comunidade da aldeia podem ser ouvidos em certas Even to this day, the chatter and village sounds of the ocasiões.