First Confirmed Breeding Record of Eurasian Sparrowhawk Accipiter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accipiters.Pdf

Accipiters The northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) are the Alaskan representatives of a group of hawks known as accipiters, with short, rounded wings (short in comparison with other hawks) and long tails. The third North American accipiter, the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is not found in Alaska. Both native species are abundant in the state but not commonly seen, for they spend the majority of their time in wooded habitats. When they do venture out into the open, the accipiters can be recognized easily by their “several flaps and a glide” style of flight. General Description: Adult northern goshawks are bluish- gray on the back, wings, and tail, and pearly gray on the breast and underparts. The dark gray cap is accented by a light gray stripe above the red eye. Like most birds of prey, female goshawks are larger than males. A typical female is 25 inches (65 cm) long, has a wingspread of 45 inches (115 cm) and weighs 2¼ pounds (1020 g) while the average male is 19½ inches (50 cm) in length with a wingspread of 39 inches (100 cm) and weighs 2 pounds (880 g). Adult sharp-shinned hawks have gray backs, wings and tails (males tend to be bluish-gray, while females are browner) with white underparts barred heavily with brownish-orange. They also have red eyes but, unlike goshawks, have no eyestrip. A typical female weighs 6 ounces (170 g), is 13½ inches (35 cm) long with a wingspread of 25 inches (65 cm), while the average male weighs 3½ ounces (100 g), is 10 inches (25 cm) long and has a wingspread of 21 inches (55 cm). -

Our Recent Bird Surveys

Breeding Birds Survey at Germantown MetroPark Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Accipiter cooperii hawk, Cooper's Corvus brachyrhynchos crow, American Accipiter striatus hawk, sharp shinned Cyanocitta cristata jay, blue Aegolius acadicus owl, saw-whet Dendroica cerulea warbler, cerulean Agelaius phoeniceus blackbird, red-winged Dendroica coronata warbler, yellow-rumped Aix sponsa duck, wood Dendroica discolor warbler, prairie Ammodramus henslowii sparrow, Henslow's Dendroica dominica warbler, yellow-throated Ammodramus savannarum sparrow, grasshopper Dendroica petechia warbler, yellow Anas acuta pintail, northern Dendroica pinus warbler, pine Anas crecca teal, green-winged Dendroica virens warbler, black-throated Anas platyrhynchos duck, mallard green Archilochus colubris hummingbird, ruby-throated Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bobolink Ardea herodias heron, great blue Dryocopus pileatus woodpecker, pileated Asio flammeus owl, short-eared Dumetella carolinensis catbird, grey Asio otus owl, long-eared Empidonax minimus flycatcher, least Aythya collaris duck, ring-necked Empidonax traillii flycatcher, willow Baeolphus bicolor titmouse, tufted Empidonax virescens flycatcher, Acadian Bombycilla garrulus waxwing, cedar Eremophia alpestris lark, horned Branta canadensis goose, Canada Falco sparverius kestrel, American Bubo virginianus owl, great horned Geothlypis trichas yellowthroat, common Buteo jamaicensis hawk, red-tailed Grus canadensis crane, sandhill Buteo lineatus hawk, red-shouldered Helmitheros vermivorus warbler, worm-eating -

Japanese Sparrowhawk Tsumi

Bird Research News Vol.2 No.2 2005. 2.10. Japanese Sparrowhawk Tsumi (Jpn) Accipiter gularis but the many individuals of the northern areas are observed to Morphology and classification move south in the autumn. The population that breeds in the Yaeyama Islands, southern Japan is classified as a distinct subspe- Classification: Accipitriformes Accipitridae cies, Ryukyu Tsumi A. g. iwasakii. Total length: ♂ 265mm ♀ 304mm Wing length: ♂ 168.51 ± 8.35mm ♀ 192.21 ± 7.13mm Habitat: Tail length: ♂ 123.5 ± 4.33mm ♀ 143.22 ± 6.61mm In Japan they occur in the woodlands in plains and mountains and Culmen length: ♂ 11.1 ± 0.34mm ♀ 13.5 ± 1.13mm even in cities. Since they nest in an isolated tree in a logged-over Tarsus length: ♂ 43-48mm ♀ 52-57mm Weight: ♂ 90g ♀ 135.8g Life history Lengths of natural wing, tail and beak (mean ± SD) are based on Hirano & Endo (unpublished data). Total length and weight are from Enomoto (1941). incubation Appearance: Male upperparts are dark gray tinged with blue and underparts are pairing period pale reddish brown from the chest to flank. The reddish brown nest building brooding vary between individuals from almost white to red brown. Eyes are laying period family period after fledging black with red tint. Legs are yellow. In the female, on the other Breeding system: hand, upperparts are dark gray and underparts are off-white with Monogamous. Extra-pair copulation is observed on rare occasions dark brown lateral bars. Eyes are yellow. Both sexes of juveniles (Ueta & Hirano 1999). have dark brown upperparts with thick brown bars on the chest and belly. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Review of the Conflict Between Migratory Birds and Electricity Power Grids in the African-Eurasian Region

CMS CONVENTION ON Distribution: General MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/Inf.10.38/ Rev.1 SPECIES 11 November 2011 Original: English TENTH MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Bergen, 20-25 November 2011 Agenda Item 19 REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION (Prepared by Bureau Waardenburg for AEWA and CMS) Pursuant to the recommendation of the 37 th Meeting of the Standing Committee, the AEWA and CMS Secretariats commissioned Bureau Waardenburg to undertake a review of the conflict between migratory birds and electricity power grids in the African-Eurasian region, as well as of available mitigation measures and their effectiveness. Their report is presented in this information document and an executive summary is also provided as document UNEP/CMS/Conf.10.29. A Resolution on power lines and migratory birds is also tabled for COP as UNEP/CMS/Resolution10.11. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION Funded by AEWA’s cooperation-partner, RWE RR NSG, which has developed the method for fitting bird protection markings to overhead lines by helicopter. Produced by Bureau Waardenburg Boere Conservation Consultancy STRIX Ambiente e Inovação Endangered Wildlife Trust – Wildlife & Energy Program Compiled by: Hein Prinsen 1, Gerard Boere 2, Nadine Píres 3 & Jon Smallie 4. -

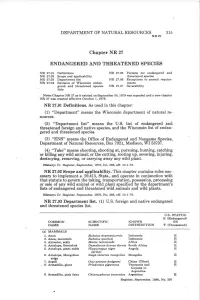

Endangered and Threatened Species

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 315 NR27 Chapter NR 27 ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES NR 27.01 Definitions NR 27 .05 Permits for endangered and NR 27.02 Scope end applicability threatened species NR 27.03 Department list NR 27 .06 Exceptions to permit require NR 27.04 Revision of Wisconsin endan ments gered and threatened species NR 27.07 Severability lists Note: Chapter NR 27 es it existed on September 30, 1979 was repealed and a new chapter NR 27 was created effective October 1, 1979. NR 27.01 Definitions. As used in this chapter: (1) "Department" means the Wisconsin department of natural re sources. (2) "Department list" means the U.S. list of endangered and threatened foreign and native species, and the Wisconsin list of endan gered and threatened species. (3) "ENS" means the Office of Endangered and Nongame Species, Department of Natural Resources, Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. (4) "Take" means shooting, shooting at, pursuing, hunting, catching or killing any wild animal; or the cutting, rooting up, severing, injuring, destroying, removing, or carrying away any wild plant. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.02 Scope and applicability. This chapter contains rules nec essary to implement s. 29.415, Stats., and operate in conjunction with that statute to govern the taking, transportation, possession, processing or sale of any wild animal or wild plant specified by the department's lists of endangered and threatened wild animals and wild plants. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.03 Department list. -

Variation in the Procoracoid Foramen in the Accipitridae

Z6f Riv. Hal. Orn., Milano, 57 (3-4): 161-184, 15-XII-19B7 STORRS L. OLSON (*) VARIATION IN THE PROCORACOID FORAMEN IN THE ACCIPITRIDAE Abstract. — The procoracoid foramen of the eoracoid is present in the great majority of genera of Accipitridae. It may be nearly or completely absent in indivi- duals of Circus and Harpagus, the taxonomic significance of which is uncertain. The procoracoid foramen is invariably absent in the genus Accipiter, although the con- dition is still unknown in Erythrotriorchis and Megatriorchis which have sometimes been synonymized with Accipiter. The presence of a well developed procoracoid fo- ramen in Urotriorchis suggests that this genus may not be as closely related to Accipiter as has been assumed. Riassunto. — Variazione nel forame procoracoideo degli Accipitridae. II forame procoracoideo del coraeoide e presente nella maggioranza del generi degli Accipitridi. Esso puo essere quasi o completamente assente in individui di Circus e di Harpagus, fatto dal significato tassonomico incerto. II forame procora- coideo e invariabilmente assente nel genere Accipiter, sebbene tale condizione sia an- cora sconosciuta per i generi Erythrotriorchis e Megatriorchis, a volte posti in sino- nimia con Accipiter. La presenza di un forame procoracoideo ben sviluppato in Uro- triorchis suggerisce che questo genere possa non essere cosi strettamente affine ad Accipiter, come e stato ritenuto. Anatomical characters that may be of use in defining natural sub- divisions of the large and complex family Accipitridae are much to be desired, as, for example, the fused condition of the phalanges of the inner toe (OLSON 1982). Another feature that shows significant variation in the family is the procoracoid process of the eoracoid, the condition of which is worth documenting not just for systematic information but also for purposes of identification of archeological and paleontological materials. -

Over-Ocean Raptor Migration in a Monsoon Regime: Spring and Autumn 2007 on Sangihe, North Sulawesi, Indonesia

FO@9TA"+ -0 %-00(35 '0*E''> Over-ocean raptor migration in a monsoon regime: spring and autumn 2007 on Sangihe North Su!a"esi Indonesia FRANCESCO $ERMI, GEORGE !2 ?OUNG, AGUS SALIM, WESLEY ,ANGIMANGEN and MARK SCHELLEKENS Buring spring and autumn -00) we carried out full season raptor migration counts on !angihe "sland, "ndonesia2 "n autumn, -;0,-'* migratory raptors were recorded2 Chinese !parrowhaw6 Accipiter soloensis comprised appro8imately (8C of the flight2 The count results indicate that the largest movements of this species towards the wintering grounds of eastern "ndonesia occur along the East Asian Oceanic Flyway, and not the Continental Flyway as previously thought2 /oth spring and autumn migrations occurred in the face of monsoon headwinds2 The relationship between migrant counts and day to day variation in wind direction in !angihe differed between the two seasons2 &ore migrants were counted during crosswind conditions in spring when their route ta6es them along closely spaced islands than during similar conditions in autumn, when they run the ris6 of being blown off course during longer over water legs2 Bisplacement over the sea by crosswinds coupled with records from other islands point to the e8istence of an additional and heretofore un6nown eastern route, involving longer water crossings, between &indanao and the northern &oluccas via the Talaud "slands2 <e gathered evidence that Chinese !parrowhaw6 behave nomadically during the non breeding season, following local food abundances of seasonal insect outbrea6s induced -

Raptors in the East African Tropics and Western Indian Ocean Islands: State of Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Status

j. RaptorRes. 32(1):28-39 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RAPTORS IN THE EAST AFRICAN TROPICS AND WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS: STATE OF ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION STATUS MUNIR VIRANI 1 AND RICHARD T. WATSON ThePeregrine Fund, Inc., 566 WestFlying Hawk Lane, Boise,1D 83709 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.--Fromour reviewof articlespublished on diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey occurringin Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands,we found most of the information on their breeding biology comesfrom subtropicalsouthern Africa. The number of published papers from the eastAfrican tropics declined after 1980 while those from subtropicalsouthern Africa increased.Based on our KnoM- edge Rating Scale (KRS), only 6.3% of breeding raptorsin the eastAfrican tropicsand 13.6% of the raptorsof the Indian Ocean islandscan be consideredWell Known,while the majority,60.8% in main- land east Africa and 72.7% in the Indian Ocean islands, are rated Unknown. Human-caused habitat alteration resultingfrom overgrazingby livestockand impactsof cultivationare the main threatsfacing raptors in the east African tropics, while clearing of foreststhrough slash-and-burnmethods is most important in the Indian Ocean islands.We describeconservation recommendations, list priorityspecies for study,and list areasof ecologicalunderstanding that need to be improved. I•y WORDS: Conservation;east Africa; ecology; western Indian Ocean;islands; priorities; raptors; research. Aves rapacesen los tropicos del este de Africa yen islasal oeste del Oc•ano Indico: estado del cono- cimiento eco16gicoy de su conservacitn RESUMEN.--Denuestra recopilacitn de articulospublicados sobre aves rapaces diurnas y nocturnasque se encuentran en Africa yen las islasal oeste del Octano Indico, encontramosque la mayoriade la informaci6n sobre aves rapacesresidentes se origina en la regi6n subtropical del sur de Africa. -

A Partial Post-Juvenile Molt and Transitional Plumage in the Shikra (Accipiter Badius) and Grey Frog Hawk ( a Ccipiter Soloensis)

THE JOURNAL OF RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF • THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 34 DECEMBER 2000 NO. 4 J. RaptorRes. 34(4) :249-261 ¸ 2000 The Raptor Research Foundation, Inc. A PARTIAL POST-JUVENILE MOLT AND TRANSITIONAL PLUMAGE IN THE SHIKRA (ACCIPITER BADIUS) AND GREY FROG HAWK ( A CCIPITER SOLOENSIS) MARC HERREMANS AND MICHEL LOUETTE RoyalMuseum for CentralAfrica, Department Zoology, Leuvensesteenweg 13, B-3080 Tervuren,Belgium ABSTRACT.--Molthas been poorly studied in the Accipitridae. Examination of museum specimens showedthat there are three age-relatedplumages in the Shikra (Accipiterbadius) and Grey Frog Hawk (A. soloensis)similar to the pattern known in the Levant Sparrowhawk(A. brevipes).The juvenile plumage with its distinctively-spottedunderside is replacedby a transitionalpost-juvenile plumage during a partial contour molt between 4-10 mo of age. More feathers on the ventral side than on the dorsal side are replaced during this first contour molt, which is arrested at variousstages of incomplete feather replace- ment. Usually, a significantpart of the ventral pattern changesfrom spotted to barred, whereby the barring is on averagemore prominent than in adults. The early development of a transitional post- juvenile plumage might be related to early sex signaling.The adult plumage replacesthe transitional post-juvenileplumage during a completemolt at about one year of age. In the subspeciesA. b.poliopsis of the Shikra, which has almost no sexual dimorphism in the adult plumage, the transitional plumage is uncommon and very poorly developed. KEYWORDS: Shikra;Accipiter badius; Greyb?og Hawk; Accipiter soloensis;Levant Sparrowhawk; Accipiter brevipes;contour molt;, transitional post-juvenile plumage. Muda parcial postjuvenil y de transicionde plumaje en Accipiterbadius y Accipitersoloensis RES0MEN.--Lamuda ha sido poco esmdiada en las Accipitridae. -

Timing and Abundance of Grey-Faced Buzzards Butastur Indicus and Other Raptors on Northbound Migration in Southern Thailand, Spring 2007–2008

FORKTAIL 25 (2009): 90–95 Timing and abundance of Grey-faced Buzzards Butastur indicus and other raptors on northbound migration in southern Thailand, spring 2007–2008 ROBERT DeCANDIDO and CHUKIAT NUALSRI We provide the first extensive migration data about northbound migrant raptors in Indochina. Daily counts were made at one site (Promsri Hill) in southern Thailand near the city of Chumphon, from late February through early April 2007–08. We identified 19 raptor species as migrants, and counted 43,451 individuals in 2007 (112.0 migrants/hr) and 55,088 in 2008 (160.6 migrants/hr), the highest number of species and seasonal totals for any spring raptor watch site in the region. In both years, large numbers of raptors were first seen beginning at 12h00, and more than 70% of the migration was observed between 14h00 and 17h00 with the onset of strong thermals and an onshore sea breeze from the nearby Gulf of Thailand. Two raptor species, Jerdon’s Baza Aviceda jerdoni and Crested Serpent Eagle Spilornis cheela, were recorded as northbound migrants for the first time in Asia. Four species composed more than 95% of the migration: Black Baza Aviceda leuphotes (mean 50.8 migrants/hr in 2007–08), Grey-faced Buzzard Butastur indicus (47.5/hr in 2007–08), Chinese Sparrowhawk Accipiter soloensis (22.3/hr in 2007–08), and Oriental Honey-buzzard Pernis ptilorhynchus (7.5/hr in 2007–08). Most (>95%) Black Bazas, Chinese Sparrowhawks and Grey-faced Buzzards were observed migrating in flocks. Grey-faced Buzzard flocks averaged 25–30 birds/ flock. Seasonally, our counts indicate that the peak of the Grey-faced Buzzard migration occurs in early to mid-March, while Black Baza and Chinese Sparrowhawk peak in late March through early April. -

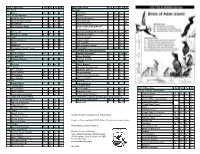

(2007): Birds of the Aleutian Islands, Alaska Please

Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi OSPREYS FINCHES Osprey Ca Ca Ac Brambling I Ca Ca EAGLES and HAWKS Hawfinch I Ca Northern Harrier I I I Common Rosefinch Ca Eurasian Sparrowhawk Ac (Ac) Pine Grosbeak Ca Bald Eagle* C C C C Asian Rosy-Finch Ac Rough-legged Hawk Ac Ca Ca Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch* C C C C OWLS (griseonucha) Snowy Owl I Ca I I Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (littoralis) Ac Short-eared Owl* R R R U Oriental Greenfinch Ca FALCONS Common Redpoll I Ca I I Eurasian Kestrel Ac Ac Hoary Redpoll Ca Ac Ca Ca Merlin Ca I Red Crossbill Ac Gyrfalcon* R R R R White-winged Crossbill Ac Peregrine Falcon* (pealei) U U C U Pine Siskin I Ac I SHRIKES LONGSPURS and SNOW BUNTINGS Northern Shrike Ca Ca Ca Lapland Longspur* Ac-C C C-Ac Ac CROWS and JAYS Snow Bunting* C C C C Common Raven* C C C C McKay's Bunting Ca Ac LARKS EMBERIZIDS Sky Lark Ca Ac Rustic Bunting Ca Ca SWALLOWS American Tree Sparrow Ac Tree Swallow Ca Ca Ac Savannah Sparrow Ca Ca Ca Bank Swallow Ac Ca Ca Song Sparrow* C C C C Cliff Swallow Ca Golden-crowned Sparrow Ac Ac Barn Swallow Ca Dark-eyed Junco Ac WRENS BLACKBIRDS Pacific Wren* C C C U Rusty Blackbird Ac LEAF WARBLERS WOOD-WARBLERS Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Wood Warbler Ac Yellow Warbler Ac Dusky Warbler Ac Blackpoll Warbler Ac DUCKS, GEESE and SWANS Kamchatka Leaf Warbler Ac Yellow-rumped Warbler Ac Emperor Goose C-I Ca I-C C OLD WORLD FLYCATCHERS "HYPOTHETICAL" species needing more documentation Snow Goose Ac Ac Gray-streaked Flycatcher Ca American Golden-plover (Ac) Greater White-fronted Goose I