PDF Ver. Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activities of the Center for American Studies, 2018

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NANZAN REVIEW OF AMERICAN STUDIES Volume 40 (2018): 139-143 Activities of the Center for American Studies, 2018 [Activities Mainly Sponsored by the Center for American Studies] Lecture Meeting Main Sponsor: Center for American Studies Joint Sponsor: The International Association for North American Ethnic Studies, Nagoya American Studies Association Date: February 25th, 2018 Time: 14:00―17:00 Venue: Conference Room 51 and 52, 5th Floor, Building Q Speaker: Jennifer L. Barker (Associate Professor, Bellarmine University) Title: Early American Movies: 1920s to 1950s Jennifer L. Barker Commemorative Photo Lecture Meeting Main Sponsor: Center for American Studies Joint Sponsor: Department of British and American Studies and Nagoya American Studies Association Date: July 14th, 2018 Time: 14:00―17:00 Venue: Conference Room 51 and 52, 5th Floor, Building Q Speaker: Michael K. Honey (Professor, University of Washington Tacoma) Title: Revisiting M.L. King’s Last Crusade 139 Michael K. Honey Commemorative Photo Lecture Meeting Main Sponsor: Center for American Studies Joint Sponsor: Center for Asia-Pacific Studies, Graduate School of International Area Studies and Nagoya American Studies Association Date: October 1st, 2018 Time: 17:00―19:00 Venue: Conference Room 51 and 52, 5th Floor, Building Q Speaker: Bruce Cumings (Professor, University of Chicago) Title: The Nuclearization and Denuclearization of Korea Bruce Cumings Commemorative Photo [Activities Co-sponsored by -

Japan Ryugaku Awards Special

6 | The Japan Times | Monday, November 30, 2020 Japan Ryugaku Awards special (Sponsored content) Schools lauded for COVID-19 response, support The number of international students At that time, many students at Japanese ties and Japanese language schools, as well ments, Takushoku University received Japan’s education. pass level N2 of the JLPT before enter- enrolled in Japanese universities and voca- language schools returned to their home as affiliated business representatives. the east grand prize, while the west grand The pandemic has severely disrupted ing a program conducted in Japanese. But tional schools is on the rise. In May 2019, countries. Since then, Japanese language This year, 176 Japanese language schools prize went to the University of Market- Japanese-language schools, which play some educators observe that students this number stood at 312,214, up from schools have selected award recipients submitted 469 votes to select 50 institu- ing and Distribution Sciences. In the cat- an important role in preparing students who have passed this exam may still have 164,000 in 2011, and the number of students based on numerous criteria. Providing tions across five categories: vocational egory for private science departments, to enroll in vocational schools and uni- trouble understanding their instructors who chose to work in Japan after graduat- easy-to-understand materials, establishing schools, private liberal arts departments, Tokyo University of Science received the versities. According to surveys conducted and classmates. Japanese language schools ing has more than doubled since 2013. separate tracks for international students, private science departments, public east grand prize and Kindai University, by Japanese language schools, approxi- generally teach their curriculum over two Supporting this influx of international simplifying application procedures and universities and graduate schools. -

Aichi Prefecture

Coordinates: 35°10′48.68″N 136°54′48.63″E Aichi Prefecture 愛 知 県 Aichi Prefecture ( Aichi-ken) is a prefecture of Aichi Prefecture Japan located in the Chūbu region.[1] The region of Aichi is 愛知県 also known as the Tōkai region. The capital is Nagoya. It is the focus of the Chūkyō metropolitan area.[2] Prefecture Japanese transcription(s) • Japanese 愛知県 Contents • Rōmaji Aichi-ken History Etymology Geography Cities Towns and villages Flag Symbol Mergers Economy International relations Sister Autonomous Administrative division Demographics Population by age (2001) Transport Rail People movers and tramways Road Airports Ports Education Universities Senior high schools Coordinates: 35°10′48.68″N Sports 136°54′48.63″E Baseball Soccer Country Japan Basketball Region Chūbu (Tōkai) Volleyball Island Honshu Rugby Futsal Capital Nagoya Football Government Tourism • Governor Hideaki Ōmura (since Festival and events February 2011) Notes Area References • Total 5,153.81 km2 External links (1,989.90 sq mi) Area rank 28th Population (May 1, 2016) History • Total 7,498,485 • Rank 4th • Density 1,454.94/km2 Originally, the region was divided into the two provinces of (3,768.3/sq mi) Owari and Mikawa.[3] After the Meiji Restoration, Owari and ISO 3166 JP-23 Mikawa were united into a single entity. In 187 1, after the code abolition of the han system, Owari, with the exception of Districts 7 the Chita Peninsula, was established as Nagoya Prefecture, Municipalities 54 while Mikawa combined with the Chita Peninsula and Flower Kakitsubata formed Nukata Prefecture. Nagoya Prefecture was renamed (Iris laevigata) to Aichi Prefecture in April 187 2, and was united with Tree Hananoki Nukata Prefecture on November 27 of the same year. -

Nagoya University Profile 2019

NAGOYA 曇 NAGOYA UNIVERSITY UNIくERSITY Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya、464-8601, Japan Phone: +81-52-789-2044 PROFILE 2019 http://en.nagoya-u.ac.jp/ PROFILE NAGOYA UNIVERSITY 2019 .. (P も .. • . . ‘ . � / 4, "" "・ .. : 戸 “ 鼻 · ^鴫 . F .7• ・ , 鳥 / ` y-..ら 99 '1 ; ‘り 0 ♦ 9•i 9 t 1 ▲ ぃ, • · り 、1.9ー ・鳴 ‘. ー ぶ '“a , 'l , .' .I ;- /“ � ぃ ァ ' 4 、 ..... n 一ー ,ー -;., .9 b し. . i― . 胃 " _ . ‘ Iけ 偏・ ト”" t 贔 0 The Nagoya University Academic Charter In recognition of the unique role of seats of learning and 3) Nagoya University shall promote international academic their historical and social missions, this document co-operation and the education of international students. It establishes the guiding principles for scholarship at Nagoya will contribute to educational and cultural exchange with University. Nagoya University maintains a culture of free other countries, especially those in Asia. and open-minded academic endeavor and aspires to contribute to the prosperity and happiness of all people through research and education in those fields studying 3 Fundamental Policies: human beings, society, and the natural world. Above all, it Research and Education System aims to foster the harmonious development of humanity 1) Nagoya University shall study the humanities, society, and science, to conduct advanced research, and to provide and nature from an inclusive viewpoint, respond to an education that encompasses the full range of the contemporary issues, and change and enrich its education humanities, the social sciences, and the natural sciences. and research system to generate new values and a body of To these ends, we outline below the goals and guidelines knowledge based on humanitarian values. -

![No.204 (English) [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3278/no-204-english-pdf-1013278.webp)

No.204 (English) [Pdf]

ISSN 2188-109X 一般社団法人 大 学 英 語 教 育 学 会 ―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――― March 2019 The Japan Association of College English Teachers No.204 ―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――― Contents Foreword (Naoko Ozeki) 1 Report from the Committee of 4 Report from Headquarters 2 Academic Affairs Reports from Chapters 5 Foreword Naoko Ozeki Vice-President of JACET Director, Committee of Academic Publication (Meiji University) To JACET members and supporters, Recently, JACET has been going through changes in terms of its evaluation of papers JACET publishes influential articles in the submitted to the JACET Journal and JACET JACET Journal, JACET International International Convention Selected Papers. One of Convention Selected Papers, and JAAL in JACET the most noticeable changes is the area of Proceedings, each of which is published annually, globalization. For example, since we have and provides an incentive for both researchers and established affiliations with various organizations instructors to do further research and improve such as JALT (Japan), AILA (international), their practice. ALAK (Korea), ETA-ROCK (Taiwan), and JACET 通信―――――――――――――――<1>―――――――――――――――――3189 RELC (Singapore), we have invited international of APA format will be a requirement for having a plenary speakers and guest speakers to our paper accepted in JACET publications. We are international conferences and summer seminars. looking forward to reading your future We have also invited these speakers to write submissions to our journals. articles about the topics they talked about at the conferences for the JACET Journals and Selected Papers. We hope that those who could not Report from the JACET Headquarters participate in the conferences or summer seminars will be able to share the main ideas and insights of Secretary General these speakers’ presentations by reading their Yukinari Shimoyama articles. -

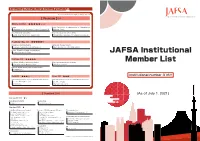

JAFSA Institutional Member List

Supporting Member(Social Business Partners) 43 ※ Classified by the company's major service [ Premium ](14) Diamond( 4) ★★★★★☆☆ Finance Medical Certificate for Visa Immunization for Studying Abroad Western Union Business Solutions Japan K.K. Hibiya Clinic Global Student Accommodation University management and consulting GSA Star Asia K.K. (Uninest) Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation Platinum‐Exe( 3) ★★★★★☆ Marketing to American students International Students Support Takuyo Corporation (Lighthouse) Mori Kosan Co., Ltd. (WA.SA.Bi.) Vaccine, Document and Exam for study abroad Tokyo Business Clinic JAFSA Institutional Platinum( 3) ★★★★★ Vaccination & Medical Certificate for Student University management and consulting Member List Shinagawa East Medical Clinic KEI Advanced, Inc. PROGOS - English Speaking Test for Global Leaders PROGOS Inc. Gold( 2) ★★★☆ Silver( 2) ★★★ Institutional number 316!! Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Access Nextage Co.,Ltd Doorkel Co.,Ltd. DISCO Inc. Mynavi Corporation [ Standard ](29) (As of July 1, 2021) Standard20( 2) ★☆ Study Abroad Information Housing・Hotel Keibunsha MiniMini Corporation . Standard( 27) ★ Study Abroad Program and Support Insurance / Risk Management /Finance Telecommunication Arc Three International Co. Ltd. Daikou Insurance Agency Kanematsu Communications LTD. Australia Ryugaku Centre E-CALLS Inc. Berkeley House Language Center JAPAN IR&C Corporation Global Human Resources Development Fuyo Educations Co., Ltd. JI Accident & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. JTB Corp. TIP JAPAN Fourth Valley Concierge Corporation KEIO TRAVEL AGENCY Co.,Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. Originator Co.,Ltd. OKC Co., Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Medical Service Co.,Ltd. WORKS Japan, Inc. Ryugaku Journal Inc. Sanki Travel Service Co.,Ltd. Housing・Hotel UK London Study Abroad Support Office / TSA Ltd. -

Conference Program Ver.1.4

Ver. 1.4 MHS2016 2016 International Symposium on Micro-NanoMechatronics and Human Science (From Micro & Nano Scale Systems to Robotics & Mechatronics Systems) Symposium on “Hyper Bio Assembler for 3D Cellular System Innovation” Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, MEXT, Japan Symposium on “Understanding brain plasticity on body representations to promote their adaptive functions” Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, MEXT, Japan Nov. 28 - 30, 2016, Nagoya, Japan November 28 (Mon) Location: Noyori Conference Hall Opening Remarks Conference Room 1 Chairperson: Fumihito Arai, Nagoya University 09:00-9:20 Prof. Toshio Fukuda, Meijo University, Japan (Honorary Chair) Prof. Tatsuo Arai, Osaka University, Japan (General Co-Chairs) Prof. Fumihito Arai, Nagoya University, Japan (General Co-Chair) Prof. Jun Ota, The University of Tokyo, Japan (General Co-Chair) Plenary Talk Conference Room 1 Chairperson: Fumihito Arai, Nagoya University 09:20-10:10 Plenary Talk 1 Microengineered Devices for Cells, Tissues and Organs Prof. Nancy Allbritton, Department of Biomedical Engineering, North Carolina State University, USA 10:10-10:20 Coffee Break Chairperson: Tatsuo Arai, Osaka University 10:20-11:10 Plenary Talk 2 Nanogel Techtonics for Biomedical Application Prof. Kazunari Akiyoshi, Department of Polymer Chemistry, Kyoto University, Japan 1 Ver. 1.4 Chairperson: Seiichi Hata, Nagoya University 11:10-12:00 Plenary Talk 3 Engineering Perfusable Blood and Lymphatic Vessels for Organ-on-Chip Platforms Prof. Noo Li Jeon, School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Seoul National University, Korea 12:00-13:00 Lunch 2 Ver. 1.4 Poster session I Poster Area(1st floor) Chairperson: Yasushi Mae, Osaka University Seiichi Hata, Nagoya University Yasuhisa Hasegawa, Nagoya University 13:00-14:00 MP-01 An Approach to Object Recognition for a Power Distribution Line Maintenance Robot. -

2020 Brochure

NAGOYA SKY JAPANESE LANGUAGE SCHOOL 名古屋SKY⽇本語学校 CONTACT US 13-22, 1-chome, Shinsakae, Naka-ward, Nagoya city, Aichi prefecture, Japan TEL: (+81)52-252-0120 ADMISSIONS PLEASE CHECK OUR WEBSITE: http://www.nagoya-sky.co.jp/ (JP/ ENG) OR E-mail us on: [email protected] SCHOOL INFORMATION LOCATION Our school is in central Nagoya (Naka ward) where most of the cultural properties and historical sites are located. Nagoya is also known as the 3rd largest city in Japan which is geographically in between Osaka and Tokyo. "Shinsakae" is where Nagoya SKY Japanese language school locates, and where students can access to varieties of facilities (supermarkets, medical center, city hall, libraries, shopping center etc.). SCHOOL COURSE & PROGRAMS Nagoya SKY Japanese language school has a total of four different courses per year. January admission ( One-year and three months course.) April admission (Two years intensive course.) July admission (One-year and nine months intensive course.) October admission (One and a half years intensive course.) For admission information please check our website or contact us by checking "page 3". Extracurricular programs for regular students. Two days (overnight) field trip for graduating students. etc. LIST OF NATIONALITIES OF REGULAR STUDENTS (2020) UKRAINE NEPAL BANGLADESH SRI LANKA MYAMAR INDONESIA VIET NAM EXTRA CURRICULAR ACTIVITIES NAGOYA CASTLE JAPANESE CULTURE EVENT HAMAMATSU (SHIZUOKA) SHIRAKAWA (GIFU) ADMISSIONS INTENSIVE LANGUAGE COURSES Requirements/ Qualifications (Applications from abroad) 12 years academic completion 【Admission process】 150 hours Japanese course completion Biodata screenings (documents) N5 level or above Japanese proficiency Interview (NAT-TEST, JLPT, J-TEST required) Certificate of Eligibility (COE) application Financially stable guarantor (parents) *Only applicants who passed admission can apply for the certificate of eligibility. -

Mechanical Engineering Letters Associate Editor SMM Masahiro ARAI

Mechanical Engineering Letters Associate Editor SMM Masahiro ARAI (Nagoya University), Yoshinobu SHIMAMURA (Shizuoka University), Kenji HIROHATA (Toshiba Corp.), Dai OKUMURA (Osaka University), Kohji MINOSHIMA (Osaka University), Takahiro KUBO (Toshiba Corp.), Hiroshi NOGUCHI (Kyusyu University), Katsuyoshi KONDOH (Osaka University), Yukio MIYASHITA (Nagaoka University of Technology), Kazuhiro OGAWA (Tohoku University), Hiroki AKASAKA (Tokyo Institute of Technology), Yoshiaki AKINIWA (Yokohama National University), Wataru NAKAO (Yokohama National University), Msaatake OHMIYA (Keio University), Toru IKEDA (Kagoshima University), Tadahiro SHIBUTANI (Yokohama National University), Hironori TOMYOH (Tohoku University), Seiichi HATA (Nagoya University), Susume TAKAHASHI (Nihon University), Satoshi KOBAYASHI (Tokyo Metropolitan University), Junpei SAKURAI (Nagoya University), Satoshi YONEYAMA (Aoyama Gakuin University), Osamu KUWAZURU (Fukui University), Fumio NARITA (Tohoku University), Takenobu SAKAI (Saitama University), Atsushi HOSOI (Waseda Univeristy), Yoji OKABE (The Univeristy of Tokyo), Shiro BIWA (Kyoto University), Tetsuya MATSUDA (University of Tsukuba), Yuko AONO (Tokyo Institute of Technology), Ryo MATSUMOTO (Osaka University), Takayuki TOKOROYAMA (Nagoya University), Hiroyuki Kousaka (Gifu University), Tetsuhide SHIMIZU (Tokyo Metropolitan University), Kazuhiro SUGA (Kogakuin University) TEP Fumiteru AKAMATSU (Osaka University), Shoji TSUSHIMA (Osaka University), Hidenori KOSAKA (Tokyo Institute of Technology), Naoki SHIKAZONO -

1. Japanese National, Public Or Private Universities

1. Japanese National, Public or Private Universities National Universities Hokkaido University Hokkaido University of Education Muroran Institute of Technology Otaru University of Commerce Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Kitami Institute of Technology Hirosaki University Iwate University Tohoku University Miyagi University of Education Akita University Yamagata University Fukushima University Ibaraki University Utsunomiya University Gunma University Saitama University Chiba University The University of Tokyo Tokyo Medical and Dental University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku (Tokyo University of the Arts) Tokyo Institute of Technology Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology Ochanomizu University Tokyo Gakugei University Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology The University of Electro-Communications Hitotsubashi University Yokohama National University Niigata University University of Toyama Kanazawa University University of Fukui University of Yamanashi Shinshu University Gifu University Shizuoka University Nagoya University Nagoya Institute of Technology Aichi University of Education Mie University Shiga University Kyoto University Kyoto University of Education Kyoto Institute of Technology Osaka University Osaka Kyoiku University Kobe University Nara University of Education Nara Women's University Wakayama University Tottori University Shimane University Okayama University Hiroshima University Yamaguchi University The University of Tokushima Kagawa University Ehime -

Stephan Irle

STEPHAN IRLE Computational Sciences and Engineering Division & Chemical Sciences Division Oak Ridge National Laboratory PO Box 2008 Bldg. 8610, Room P-291 Oak Ridge, TN 37831-6493, U.S.A. Phone: +1-865-574-7192 Fax: +1-865-576-4368 E-mail: [email protected] https://www.ornl.gov/staff-profile/stephan-irle PERSONAL • Married, one child. • Citizen of Germany. • Permanent resident of Japan since February 29, 2012. • Former permanent resident of the U.S.A., A# 095-237-730. EDUCATION & TRAINING • Doctor of Philosophy, March 17, 1997. Institute of Theoretical Chemistry and Radiation Chemistry, University of Vienna, Austria Thesis: “Quantum chemical model studies on doped oligothiophenes and oligo(p-phenyls)” Supervisor: Prof. Hans Lischka. • Master of Science (Summa Cum Laude), September 30, 1992. Theoretical Chemistry, University of Siegen, Germany Thesis: “Characterization of Atoms and Chemical Bonds in Molecules by Means of the Electron Density” Supervisor: Prof. W. H. Eugen Schwarz. AWARDS AND HONORS • Funded research contracts from ACS-PRF, NSF, ONR, ORNL Laboratory Directed Research & Developed (LDRD) (U.S.A.); AC21, JSPS, JST, MEXT, NIFS (Japan), ERC (European Union); IAEA (United Nations); and DENSO Corporation (Japan). • Author Profile, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Early View (2017). DOI: 10.1002/anie.201712472 • Award from the NanotechJapan Nanotechnology Platform: “Six Major Results of 2016 from Nanotechnology Platform Japan” (平成28年度利用6大成果賞) for: "The material development of liquid crystal glue that can be exfoliated by light even at high temperature" (高温でも使える、光ではがせる液晶接着材料の開発), February 17, 2017. • Adjunct Professorship, Institute for Computational Science (IACS), Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, U.S.A., October 2015 – September 2018. -

2 Dec. 2019 Meijo University, Nagoya, JAPAN the Asia Color Association (ACA) Is Pleased to Invite You to Nagoya in Japan for ACA2019

Call for Papers The 5th Asia Color Association Conference (ACA2019 Nagoya) 29 Nov. - 2 Dec. 2019 Meijo University, Nagoya, JAPAN The Asia Color Association (ACA) is pleased to invite you to Nagoya in Japan for ACA2019. This Meeting will provide a unique forum, bringing together researchers, academics, students, artists, architects, industrialists, engineers, designers, computer scientists, lighting experts, media professionals, exhibitors and business leaders. It is hoped that attendants can expand knowledge and experience from listening to papers presented, reading posters, appreciating art works, and discussing each other. The theme of ACA2019 is “Color Communications” . Color has the power to change the world and future and it is increased through communications. It’ s just before the Tokyo Olympics will be held in 2020. We anticipate seeing around 200 delegates from all over the Asia and enjoying this conference in “Color Communications” . The fields to cover are listed below but not limited to those. Tokyo Fields and Topics: Kyoto 1. Color vision: Color vision, Color physiology, Color appearance Nagoya 2. Quality of life: Universal color design, Color deficiency, Elderly vision 3. Color psychology: Color culture, Color art, Color aesthetic, Color education, Color experience, Color emotion and preference 4. Color design: Color in product design, Color in fashion, Color environment, Personal color 5. Color application: Color physics and engineering, Color in printing and media, Color in packaging, Color in agriculture, Color in architecture, Urban design 6. Color in health and cosmetics: Color in medicine, Color in food, Color in cosmetics, Color of skin 7. Color technology: Color measurement, Color notation, Color difference, Color light, Color lighting, Color materials 8.