SERBIAN‐ITALIAN RELATIONS: History and Modern Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (Excepts)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts) Citation: “Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts),” October 22, 1962, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Italian Senate Historical Archives [the Archivio Storico del Senato della Repubblica]. Translated by Leopoldo Nuti. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115421 Summary: The few excerpts about Cuba are a good example of the importance of the diaries: not only do they make clear Fanfani’s sense of danger and his willingness to search for a peaceful solution of the crisis, but the bits about his exchanges with Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Carlo Russo, with the Italian Ambassador in London Pietro Quaroni, or with the USSR Presidium member Frol Kozlov, help frame the Italian position during the crisis in a broader context. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Italian Contents: English Translation The Amintore Fanfani Diaries 22 October Tonight at 20:45 [US Ambassador Frederick Reinhardt] delivers me a letter in which [US President] Kennedy announces that he must act with an embargo of strategic weapons against Cuba because he is threatened by missile bases. And he sends me two of the four parts of the speech which he will deliver at midnight [Rome time; 7 pm Washington time]. I reply to the ambassador wondering whether they may be falling into a trap which will have possible repercussions in Berlin and elsewhere. Nonetheless, caught by surprise, I decide to reply formally tomorrow. I immediately called [President of the Republic Antonio] Segni in Sassari and [Foreign Minister Attilio] Piccioni in Brussels recommending prudence and peace for tomorrow’s EEC [European Economic Community] meeting. -

Lettera Da San G Iorgio

CONTACTS PROGRAMMES (MARCH – AUGUST 2016) PATRONS FRIENDS OF SAN GIORGIO Fondazione Virginio Bruni Tedeschi Giorgio Lettera da San Marco Brunelli Pentagram Stiftung Rolex Institute Year XVIII, number 34. Six-monthly publication. March – August 2016 Giannatonio Guardi, Neptune, detail, private collection Spedizione in A.P. Art. 2 Comma 20/c Legge 662/96 DCB VE. Tassa pagata / Taxe perçue CONTACTS PROGRAMMES (MARCH – AUGUST 2016) PATRONS FRIENDS OF SAN GIORGIO Fondazione Virginio Bruni Tedeschi Giorgio Lettera da San Marco Brunelli Pentagram Stiftung Rolex Institute Year XVIII, number 34. Six-monthly publication. March – August 2016 Giannatonio Guardi, Neptune, detail, private collection Spedizione in A.P. Art. 2 Comma 20/c Legge 662/96 DCB VE. Tassa pagata / Taxe perçue 16 FEB VENICE, ISLAND OF SAN GIORGIO MAGGIORE 23 APR, 21 MAY, 25 JUN VENICE, ISLAND OF SAN GIORGIO MAGGIORE LETTERA DA SAN GIORGIO CONTACTS International Conference Paolo Venini and His Furnace Concert Series e Complete Beethoven String Quartets PUBLISHED BY SECRETARY’S OFFICE ISTITUTO DI STORIA DELL’ARTE INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD 1 MAR – 31 DIC VENICE, ISLAND OF SAN GIORGIO MAGGIORE 25 – 30 APR VENICE, ISLAND OF SAN GIORGIO MAGGIORE Fondazione Giorgio Cini onlus tel. +39 041 2710229 – fax +39 041 5223563 Luca Massimo Barbero, director Maurice Aymard e Replica Project International Workshop and Symposium Accademia Monteverdi Isola di San Giorgio Maggiore, 1 [email protected] Secretary’s oce: tel. +39 041 2710230 – +39 041 2710239 Brenno Boccadoro 30124 Venezia fax +39 041 5205842 Steven Feld PRESS OFFICE 3-10-17 MAR VENICE, ISLAND OF SAN GIORGIO MAGGIORE 2 – 4 MAY VENICE, ISLAND OF SAN GIORGIO MAGGIORE tel. -

Quaderni D'italianistica : Revue Officielle De La Société Canadienne

ANGELO PRINCIPE CENTRING THE PERIPHERY. PRELIMINARY NOTES ON THE ITALLVN CANADL\N PRESS: 1950-1990 The Radical Press From the end of the Second World War to the 1980s, eleven Italian Canadian radical periodicals were published: seven left-wing and four right- wing, all but one in Toronto.' The left-wing publications were: II lavoratore (the Worker), La parola (the Word), La carota (the Carrot), Forze nuove (New Forces), Avanti! Canada (Forward! Canada), Lotta unitaria (United Struggle), and Nuovo mondo (New World). The right-wing newspapers were: Rivolta ideale (Ideal Revolt), Tradizione (Tradition), // faro (the Lighthouse or Beacon), and Occidente (the West or Western civilization). Reading these newspapers today, one gets the impression that they were written in a remote era. The socio-political reality that generated these publications has been radically altered on both sides of the ocean. As a con- sequence of the recent disintegration of the communist system, which ended over seventy years of East/West confrontational tension, in Italy the party system to which these newspapers refer no longer exists. Parties bear- ing new names and advancing new policies have replaced the older ones, marking what is now considered the passage from the first to the second Republic- As a result, the articles on, or about, Italian politics published ^ I would like to thank several people who helped in different ways with this paper. Namely: Nivo Angelone, Roberto Bandiera, Damiano Berlingieri, Domenico Capotorto, Mario Ciccoritti, Elio Costa, Celestino De luliis, Odoardo Di Santo, Franca lacovetta, Teresa Manduca, Severino Martelluzzi, Roberto Perin, Concetta V. Principe, Guido Pugliese, Olga Zorzi Pugliese, and Gabriele Scardellato. -

Forced Labour in Serbia Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944

Forced Labour in Serbia Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944 edited by: Sanela Schmid Milovan Pisarri Tomislav Dulić Zoran Janjetović Milan Koljanin Milovan Pisarri Thomas Porena Sabine Rutar Sanela Schmid 1 Project partners: Project supported by: Forced Labour in Serbia 2 Producers, Consumers and Consequences . of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944 This collection of scientific papers on forced labour during the Second World War is part of a wider research within the project "Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour - Serbia 1941-1944", which was implemented by the Center for Holocaust Research and Education from Belgrade in partnership with Humboldt University, Berlin and supported by the Foundation "Remembrance, Responsibility and Future" in Germany. ("Stiftung Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft" - EVZ). 3 Impressum Forced Labour in Serbia Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour 1941-1944 Published by: Center for Holocaust Research and Education Publisher: Nikola Radić Editors: Sanela Schmid and Milovan Pisarri Authors: Tomislav Dulić Zoran Janjetović Milan Koljanin Milovan Pisarri Thomas Porena Sabine Rutar Sanela Schmid Proofreading: Marija Šapić, Marc Brogan English translation: Irena Žnidaršić-Trbojević German translation: Jovana Ivanović Graphic design: Nikola Radić Belgrade, 2018. Project partners: Center for Holocaust Research and Education Humboldt University Berlin Project is supported by: „Remembrance, Responsibility And Future“ Foundation „Stiftung Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft“ - EVZ Forced Labour in Serbia 4 Producers, Consumers and Consequences . of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944 Contents 6 Introduction - Sanela Schmid and Milovan Pisarri 12 Milovan Pisarri “I Saw Jews Carrying Dead Bodies On Stretchers”: Forced Labour and The Holocaust in Occupied Serbia 30 Zoran Janjetović Forced Labour in Banat Under Occupation 1941 - 1944 44 Milan Koljanin Camps as a Source of Forced Labour in Serbia 1941 - 1944 54 Photographs 1 62 Sabine Rutar Physical Labour and Survival. -

Arve Faucigny Genevois Albanais Pays Du Rhône » a Été Scindé

Crédit : BlancRibotSavoiephotoMont / ARVE FAUCIGNY GENEVOIS Edition 2021 Dans l’économie touristique de Savoie Mont Blanc, le secteur Arve - Faucigny - Genevois - Albanais - Pays du Rhône, représente : • 4% des lits touristiques • 7% des emplois liés au tourisme • 4% de la fréquentation ski nordique en journées skieurs CAPACITE D’ACCUEIL Source : Observatoire SMBT 2020 nombre de lits CARACTERISTIQUES DU TERRITOIRE • Superficie : 1 316 km² • 130 communes • 337 738 habitants (source : INSEE 2018) • Soit 27% de la population de Savoie Mont Blanc et 41% de la population du département de Haute-Savoie • Taux d’évolution annuel : +2,5% pour la période 1999-2018 Evolution de la population résidente • 58 800 lits touristiques (9 705 structures) • 4% de la capacité d’accueil de Savoie Mont Blanc • 8% de la capacité d’accueil de la Haute-Savoie • 20% sont des lits marchands (12 000 lits) • L’hôtellerie représente 43% de l’offre marchande • Les campings constituent le second type d’’établissements avec 2 200 lits (18% des lits marchands) Le mode de comptage des lits touristiques (en particulier non marchands) ayant été modifié, la comparaison avec les données des années antérieures n’est pas réalisable. Chiffres disponibles au 30/06/2021 1/7 FREQUENTATION DES HEBERGEMENTS MARCHANDS : L’HOTELLERIE Source : INSEE - DGE NB1 : en 2019, l’INSEE a modifié les modalités de l’enquête hôtellerie entraînant une rupture de série statistique. Les données ont été recalculées depuis 2012. Les séries publiées antérieurement ne doivent pas être comparées à cette nouvelle série. NB2 : en 2020, la crise sanitaire a impacté l’ouverture des établissements et suspendu le déroulement des enquêtes de fréquentation de l’INSEE. -

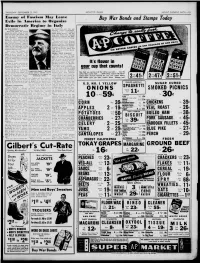

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

Refractory Migrants. Fascist Surveillance on Italians in Australia 1922-1943

Refractory Migrants. Fascist Surveillance on Italians in Australia 1922-1943 by Gianfranco Cresciani Gianfranco Cresciani emigrated University of New South Wales in from Trieste to Sydney in 1962. He 2005, in recognition of worked for EPT, the Ethnic Affairs “distinguished eminence in the field Commission and the Ministry for of history”. In 2004 the Italian the Arts of the NSW Government Government awarded him the on cultural and migration issues. In honour of Cavaliere Ufficiale 1989 and 1994 he was member of dell‟Ordine al Merito for facilitating the Australian Delegation re- cultural exchanges between Italy negotiating with the Italian and Australia. He has produced Government the Italo-Australian books, articles, exhibitions and Cultural Agreement. Master of Arts radio and television programs in (First Class Honours) from Sydney Australia and Italy on the history of University in 1978. Doctor of Italian migration to Australia. Letters, honoris causa, from the There are exiles that gnaw and others that are like consuming fire. There is a heartache for the murdered country… - Pablo Neruda We can never forget what happened to our country and we must always remind those responsible that we know who they are. - Elizabeth Rivera One of the more salient and frightening aspects of European dictatorships during the Twentieth Century, in their effort to achieve totalitarian control of 8 their societies, was the grassroots surveillance carried out by their state security organisations, of the plots and machinations of their opponents. Nobody described better this process of capillary penetration in the minds and conditioning of the lives of people living under Communist or Fascist regimes than George Orwell in his book Nineteen Eighty-Four (1), published in 1949 and warning us on the danger of Newspeak, Doublethink, Big Brother and the Thought Police. -

Emancipation in St. Croix; Its Antecedents and Immediate Aftermath

N. Hall The victor vanquished: emancipation in St. Croix; its antecedents and immediate aftermath In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 58 (1984), no: 1/2, Leiden, 3-36 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl N. A. T. HALL THE VICTOR VANQUISHED EMANCIPATION IN ST. CROIXJ ITS ANTECEDENTS AND IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH INTRODUCTION The slave uprising of 2-3 July 1848 in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, belongs to that splendidly isolated category of Caribbean slave revolts which succeeded if, that is, one defines success in the narrow sense of the legal termination of servitude. The sequence of events can be briefly rehearsed. On the night of Sunday 2 July, signal fires were lit on the estates of western St. Croix, estate bells began to ring and conch shells blown, and by Monday morning, 3 July, some 8000 slaves had converged in front of Frederiksted fort demanding their freedom. In the early hours of Monday morning, the governor general Peter von Scholten, who had only hours before returned from a visit to neighbouring St. Thomas, sum- moned a meeting of his senior advisers in Christiansted (Bass End), the island's capital. Among them was Lt. Capt. Irminger, commander of the Danish West Indian naval station, who urged the use of force, including bombardment from the sea to disperse the insurgents, and the deployment of a detachment of soldiers and marines from his frigate (f)rnen. Von Scholten kept his own counsels. No troops were despatched along the arterial Centreline road and, although he gave Irminger permission to sail around the coast to beleaguered Frederiksted (West End), he went overland himself and arrived in town sometime around 4 p.m. -

HCS — History of Classical Scholarship

ISSN: 2632-4091 History of Classical Scholarship www.hcsjournal.org ISSUE 1 (2019) Dedication page for the Historiae by Herodotus, printed at Venice, 1494 The publication of this journal has been co-funded by the Department of Humanities of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology of Newcastle University Editors Lorenzo CALVELLI Federico SANTANGELO (Venezia) (Newcastle) Editorial Board Luciano CANFORA Marc MAYER (Bari) (Barcelona) Jo-Marie CLAASSEN Laura MECELLA (Stellenbosch) (Milano) Massimiliano DI FAZIO Leandro POLVERINI (Pavia) (Roma) Patricia FORTINI BROWN Stefan REBENICH (Princeton) (Bern) Helena GIMENO PASCUAL Ronald RIDLEY (Alcalá de Henares) (Melbourne) Anthony GRAFTON Michael SQUIRE (Princeton) (London) Judith P. HALLETT William STENHOUSE (College Park, Maryland) (New York) Katherine HARLOE Christopher STRAY (Reading) (Swansea) Jill KRAYE Daniela SUMMA (London) (Berlin) Arnaldo MARCONE Ginette VAGENHEIM (Roma) (Rouen) Copy-editing & Design Thilo RISING (Newcastle) History of Classical Scholarship Issue () TABLE OF CONTENTS LORENZO CALVELLI, FEDERICO SANTANGELO A New Journal: Contents, Methods, Perspectives i–iv GERARD GONZÁLEZ GERMAIN Conrad Peutinger, Reader of Inscriptions: A Note on the Rediscovery of His Copy of the Epigrammata Antiquae Urbis (Rome, ) – GINETTE VAGENHEIM L’épitaphe comme exemplum virtutis dans les macrobies des Antichi eroi et huomini illustri de Pirro Ligorio ( c.–) – MASSIMILIANO DI FAZIO Gli Etruschi nella cultura popolare italiana del XIX secolo. Le indagini di Charles G. Leland – JUDITH P. HALLETT The Legacy of the Drunken Duchess: Grace Harriet Macurdy, Barbara McManus and Classics at Vassar College, – – LUCIANO CANFORA La lettera di Catilina: Norden, Marchesi, Syme – CHRISTOPHER STRAY The Glory and the Grandeur: John Clarke Stobart and the Defence of High Culture in a Democratic Age – ILSE HILBOLD Jules Marouzeau and L’Année philologique: The Genesis of a Reform in Classical Bibliography – BEN CARTLIDGE E.R. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message After the Oath*

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message after the Oath* At the general assembly of the House of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic, on Wednesday, 12 March 1946, the President of the Republic read the following message: Gentlemen: Right Honourable Senators and Deputies! The oath I have just sworn, whereby I undertake to devote myself, during the years awarded to my office by the Constitution, to the exclusive service of our common homeland, has a meaning that goes beyond the bare words of its solemn form. Before me I have the shining example of the illustrious man who was the first to hold, with great wisdom, full devotion and scrupulous impartiality, the supreme office of head of the nascent Italian Republic. To Enrico De Nicola goes the grateful appreciation of the whole of the people of Italy, the devoted memory of all those who had the good fortune to witness and admire the construction day by day of the edifice of rules and traditions without which no constitution is destined to endure. He who succeeds him made repeated use, prior to 2 June 1946, of his right, springing from the tradition that moulded his sentiment, rooted in ancient local patterns, to an opinion on the choice of the best regime to confer on Italy. But, in accordance with the promise he had made to himself and his electors, he then gave the new republican regime something more than a mere endorsement. The transition that took place on 2 June from the previ- ous to the present institutional form of the state was a source of wonder and marvel, not only by virtue of the peaceful and law-abiding manner in which it came about, but also because it offered the world a demonstration that our country had grown to maturity and was now ready for democracy: and if democracy means anything at all, it is debate, it is struggle, even ardent or * Message read on 12 March 1948 and republished in the Scrittoio del Presidente (1948–1955), Giulio Einaudi (ed.), 1956. -

Bassin Albanais – Annecien

TABLEAU I : BASSIN ALBANAIS – ANNECIEN COLLEGES COMMUNES ET ECOLES René Long ALBY -SUR -CHERAN ; ALLEVES ; CHAINAZ -LES -FRASSES ; CHAPEIRY ; CUSY ; GRUFFY ; HERY -SUR -ALBY ; MURES ; SAINT - ALBY-SUR-CHERAN SYLVESTRE ; VIUZ-LA-CHIESAZ Les Balmettes ANNECY - Annecy : groupes scolaires Vaugelas, La Prairie, Quai Jules Philippe (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil ANNECY- ANNECY Départemental ou collège) ANNECY- Annecy : groupes scolaires Carnot, La Plaine (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège) , Le Raoul Blanchard Parmelan (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Les Romains, Quai Jules Philippe (selon un ANNECY- ANNECY listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Vallin-Fier (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège) Les Barattes ANNECY- Annecy : groupes scolaires Le Parmelan (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Novel (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège); ANNECY- Annecy-le-Vieux (selon un listing de rues ANNECY- ANNECY-LE-VIEUX précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège); BLUFFY ; MENTHON-SAINT-BERNARD ; TALLOIRES-MONTMIN ; VEYRIER-DU-LAC ANNECY-Annecy : groupes scolaires Vallin-Fier (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), La Plaine Evire (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil Départemental ou collège), Novel (selon un listing de rues précis – cf. Conseil ANNECY- ANNECY-LE-VIEUX Départemental ou