UNICEF Lake Chad Basin Cholera Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

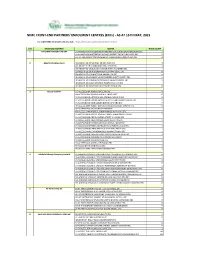

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Report of the Technical Committee Om

REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS FOR THE APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE January 2000 Contents: Volume I: Main Report Chapter One: Preliminary Matters Preamble Terms of Reference Modus Operandi Chapter Two: Consideration of Various Sections of the Constitution in Relation to Application of Sharia A. Section 4(6) B. Section 5(2) C. Section 6(2) D. Section 10 E. Section 38 F. Section 275(1) G. Section 277 Chapter Three: Observations and Recommendations 1. General Observations 2. Specific Recommendations 3. General Recommendations Conclusion Appendix A: List of all the Groups, Associations, Institutions and Individuals Contacted by the Committee Volume II: Verbatim Proceedings Zone 1: Funtua: Funtua, Bakori, Danja, Faskari, Dandume and Sabuwa Zone 2: Malumfashi: Malumfashi, Kafur, Kankara and Musawa Zone 3: Dutsin-Ma: Dutsin-Ma, Danmusa, Batsari, Kurfi and Safana Zone 4: Kankia: Kankia, Ingawa, Kusada and Matazu Zone 5: Daura: Daura, Baure, Zango, Mai’adua and Sandamu Zone 6: Mani: Mani, Mashi, Dutsi and Bindawa Zone 7: Katsina: Katsina, Kaita, Rimi, Jibia, Charanchi and Batagarawa 1 Ostien: Sharia Implementation in Northern Nigeria 1999-2006: A Sourcebook: Supplement to Chapter 2 REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE VOLUME I: MAIN REPORT CHAPTER ONE Preamble The Committee was inaugurated on the 20th October, 1999 by His Excellency, the Governor of Katsina State, Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’adua, at the Council Chambers, Government House. In his inaugural address, the Governor gave four point terms of reference to the Committee. He urged members of the Committee to work towards realising the objectives for which the Committee was set up. -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 37 (31 January 2021)

FLASH REPORT #37: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria Nigeria 25 - 31 JANUARY 2021 Casualties: Movement Trigger: 160 Individuals 9 Individuals Armed attacks OVERVIEW The crisis in Nigeria’s North Central and North West zones, which involves long-standing tensions between NIGER REPUBLIC ethnic and religious groups; attacks by criminal Kaita Mashi Mai'adua Jibia groups; and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and Katsina Daura Zango Dutsi Faskari Batagarawa Mani Rimi Safana grand larceny along major highways) led to a fresh Batsari Baure Bindawa wave of population displacement. 134 Kurfi Charanchi Ingawa Sandamu Kusada Dutsin-Ma Kankia Following these events, a rapid assessment was Katsina Matazu conducted by DTM (Displacement Tracking Matrix) Dan Musa Jigawa Musawa field staff between 25 and 31 January 2021, with the Kankara purpose of informing the humanitarian community Malumfashi Katsina Kano Faskari Kafur and government partners in enabling targeted Bakori response. Flash reports utilise direct observation and Funtua Dandume Danja a broad network of key informants to gather represen- Sabuwa tative data and collect information on the number, profile and immediate needs of affected populations. NIGERIA Latest attacks affected 160 individuals, including 14 injuries and 9 fatalities, in Makurdi LGA of Benue State and Faskari LGA of Katsina State. The attacks caused Kaduna people to flee to neighbouring localities. SEX (FIG. 1) Plateau Federal Capital Territory 39% Nasarawa X Affected Population 61% Male Makurdi International border Female 26 State Guma Agatu Benue Makurdi LGA Apa Gwer West Tarka Oturkpo Gwer East Affected LGAs Gboko Ohimini Konshisha Ushongo The map is for illustration purposes only. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

GEF Prodoc TRI Cameroon 28 02 18

International Union for the Conservation of Nature Country: Cameroon PROJECT DOCUMENT Project Title: Supporting Landscape Restoration and Sustainable Use of local plant species and tree products (Bambusa ssp, Irvingia spp, etc) for Biodiversity Conservation, Sustainable Livelihoods and Emissions Reduction in Cameroon BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT The Republic of Cameroon has a diverse ecological landscape, earning her the title “Africa in Miniature”. The southern portions of Cameroon’s forests are part of the Congo Basin forest ecosystem, the second largest remaining contiguous block of rainforest on Earth, after the Amazon. In addition to extensive Mangrove belts, Cameroon also holds significant portions of the Lower Guinea Forest Ecosystems and zones of endemism extending into densely settled portions of the Western Highlands and Montagne forests. The North of the country comprising the Dry Sudano-Sahelian Savannah Zones is rich in wildlife, and home to dense human and livestock populations. Much of the population residing in these areas lives in extreme poverty. This diversity in biomes makes Cameroon one of the most important and unique hotspots for biodiversity in Africa. However, human population growth, migrations, livelihoods strategies, rudimentary technologies and unsustainable land use for agriculture and small-scale forestry, energy and livestock, are contributing to biodiversity loss and landscape degradation in Cameroon. Despite strong institutional frameworks, forest and environmental policies/legislation, and a human resource capital, Cameroon’s network of biomes that include all types of forests, tree-systems, savannahs, agricultural mosaics, drylands, etc., are progresively confronted by various forms of degradation. Degradation, which is progressive loss of ecosystem functions (food sources, water quality and availability, biodversity, soil fertility, etc), now threatens the livelihoods of millions of Cameroonians, especially vulnerable groups like women, children and indigenous populations. -

House of Reps Order Paper Thursday 15 July, 2021

121 FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY (2019–2023) THIRD SESSION NO. 14 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Thursday 15 July 2021 1. Prayers 2. National Pledge 3. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 4. Oaths 5. Messages from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Messages from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 7. Messages from Other Parliament(s) (if any) 8. Other Announcements (if any) 9. Petitions (if any) 10. Matters of Urgent Public Importance 11. Personal Explanation PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Federal College of Education (Technical) Aghoro, Bayelsa State (Establishment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1429) (Hon. Agbedi Yeitiemone Frederick) - First Reading. 2. National Eye Care Centre, Kaduna (Establishment, Etc) Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1439) (Hon. Pascal Chigozie Obi) - First Reading. 3. Electronic Government (e-Government) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1432) (Hon. Sani Umar Bala) - First Reading. 4. Federal Medical Centre Zuru (Establishment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1443) (Hon. Kabir Ibrahim Tukura) - First Reading. 5. National Centre for Agricultural Mechanization Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021(HB. 1445) (Hon. Sergius Ogun) - First Reading. 122 Thursday 15 July 2021 No. 14 6. Industrial Training Fund Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1447) (Hon. Patrick Nathan Ifon) - First Reading. 7. Fiscal Responsibility Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1534) (Hon. Satomi A. Ahmed) - First Reading. 8. Federal Highways Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1535) (Hon. Satomi A. Ahmed) - First Reading. 9. Border Communities Development Agency (Establishment) Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. 1536) (Hon. Satomi A. Ahmed) - First Reading. 10. Borstal Institutions and Remand Centres Act (Amendment) Bill, 2021 (HB. -

Analysis of Crime in Katsina Metropolitan Area, Katsina State

ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE, NIGERIA BY Ahmed Barde, ABDULLAHI B.Sc (A.B.U. Zaria) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN REMOTE SENSING AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA NOVEMBER, 2018 ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE, NIGERIA BY Ahmed Barde, ABDULLAHI B.Sc (A.B.U. Zaria) P16PSGS8540 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN REMOTE SENSING AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA NOVEMBER, 2018 ii DECLARATION I declare that this project research titled‟ “ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE NIGERIA” Wasconducted by me under the supervision of DR. A.K Usman and DR.B. AkpuDepartment of Geography and Environmental Management and it is a record of my own work and has not been submitted for the award of Masters Degree, diploma or any other qualification in any other institution. All information and excerpts from the work of any other has been acknowledged by means of references. ABDULLAHI AHMED BARDE ______________________ ___________________ Signature Date iii CERTIFICATION This dissertation entitled “ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE NIGERIA” meets the regulations governing the award of masters‟ degree of Remote Sensing and GIS of Ahmadu Bello University and approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. -

Deforestation Trends in the Congo Basin Reconciling Economic Growth and Forest Protection

Deforestation Trends in the Congo Basin Reconciling Economic Growth and Forest Protection WORKING PAPer 2 | Logging Nina Doetinchem Carole Megevand with Loic Braune Hari Dulal APRIL 2013 Deforestation Trends in the Congo Basin Reconciling Economic Growth and Forest Protection WORKING PAPer 2 | Logging Nina Doetinchem Carole Megevand with Loic Braune Hari Dulal APRIL 2013 Working Paper 2: Logging iii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMEntS .........................................................................v ACRONYMS................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 1 chaPTER 1. LOGGinG ActiVitiES in thE CONGO BASin .................................. 3 Export-oriented Industrial Logging Sector ................................................... 4 Contribution to economic growth and employment .................................... 4 Significant progress on sustainable forest management ................................. 5 Industrial timber production ............................................................ 8 The booming informal sector .......................................................... 12 A long overlooked sector .......................................................... 12 An unregulated sector that does not capture its full socioeconomic potential ...... 13 …and generates great pressures on natural forests ................................ 14 Unmet domestic demand ........................................................ -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 26 June 2020

FLASH REPORT: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria. Nigeria 22 - 26 JUNE 2020 Aected Population: Casualties: Movement Trigger: 2,349 Individuals 3 Individuals Armed attacks OVERVIEW Maikwama 219 The crisis in Nigeria’s North Central and North West zones, which involves long-standing Dandume tensions between ethnic and linguis�c groups; a�acks by criminal groups; and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and grand larceny along major highways) led to fresh wave of popula�on displacement. Kaita Mashi Mai'adua Jibia Shinkafi Katsina Daura Zango Dutsi Batagarawa Mani Safana Latest a�acks affected 2,349 individuals, includ- Zurmi Rimi Batsari Baure Maradun Bindawa Kurfi ing 18 injuries and 3 fatali�es, in Dandume LGA Bakura Charanchi Ingawa Jigawa Kaura Namoda Sandamu Katsina Birnin Magaji Kusada Dutsin-Ma Kankia (Katsina) and Bukkuyum LGA (Zamfara) between Talata Mafara Bungudu Matazu Dan Musa 22 - 26 June, 2020. The a�acks caused people to Gusau Zamfara Musawa Gummi Kankara flee to neighboring locali�es. Bukkuyum Anka Tsafe Malumfashi Kano Faskari Kafur Gusau Bakori A rapid assessment was conducted by field staff Maru Funtua Dandume Danja to assess the impact on people and immediate Sabuwa needs. ± GENDER (FIG. 1) Kaduna X Affected PopulationPlateau 42% Kyaram 58% Male State Bukkuyum 2,130 Female Federal Capital Territory LGA Nasarawa Affected LGAs The map is for illustration purposes only. The depiction and use of boundaries, geographic names and related data shown are not warranted to be error free nor do they imply judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or accpetance of such boundaries by MOST NEEDED ASSISTANCE (FIG. -

2018/2019 Annual School Census Report

Foreword Successful education policies are formed and supported by accurate, timely and reliable data, to improve governance practices, enhance accountability and ultimately improve the teaching and learning process in schools. Considering the importance of robust data collection, the Planning, Research and Statistics (PRS) Department, Katsina State Ministry of Education prepares and publishes the Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of both Public and Private Schools on an annual basis. This is in compliance with the National EMIS Policy and its implementation. The Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of 2018-2019 is the outcome of the exercise conducted between May and June 2019, through a rigorous activities that include training Head Teachers and Teachers on School Records Keeping; how to fill ASC questionnaire using school records; data collection, validation, entry, consistency checks and analysis. This publication is the 13th Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of all Schools in the State. In line with specific objectives of National Education Management Information System (NEMIS), this year’s ASC has obtained comprehensive and reliable data where by all data obtained were from the primary source (the school’s head provide all data required from schools records). Data on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) of basic education and post basic to track the achievement of the State Education Sector Operational Plan (SESOP) as well as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); feed data into the National databank to strengthen NEMIS for national and global reporting. The report comprises of educational data pertaining to all level both public and private schools ranging from pre-primary, primary, junior secondary and senior secondary level. -

2Nd-Admission-List-CSE-2021.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SOFTWARE ENGINEERING SECOND ADMISSION LIST 2020/2021 ACADEMIC SESSION S/N NAME JAMB NO LG STATE REMARK 1 ZAKARI SANI 21109851CA KANKIA KATSINA 2 ABDULLAHI USMAN 21108346EA BATAGARAWA KATSINA 3 NURADDEEN SHAFI'U ABDULLAHI 21118540IF KATSINA KATSINA 4 MU'AZU IBRAHIM GAFAI 21008910IF KATSINA KATSINA 5 MUKHTAR AMMAR 21021462CF KATSINA KATSINA 6 NURA IBRAHIM SHU'AIBU 21114941DA KATSINA KATSINA 7 USMAN MUHAMMAD 21124251DA KATSINA KATSINA 8 ABDULRAHIM IMRANA 21134389HA KATSINA KATSINA 9 ABDULLAHI NASIR 21108913FF KATSINA 10 ABDULLAHI USMAN 21108346EA RIMI KATSINA 11 ABDULKADIR YUSUF 21116697IF KURFI KATSINA 12 KABIR SURAJO 21124632CF RIMI KATSINA 13 HUSSAINI ALAMIN DANHAIRE 21125594GA MUSAWA KATSINA 14 USMAN SULAIMAN BALA 21109826FA FASKARI KATSINA 15 KHADIJA IBRAHIM 21110114DF MALUMFASHI KATSINA 16 DAHIRU ABUBAKAR TANKURI 21113099CF JIBIA KATSINA 17 HUSSAINI ABBAS ADAMU 21115778CF MATAZU KATSINA 18 AHMAD ARAFAT 21108787CA RIMI KATSINA 19 SANI ABDULLAHI HALLIRU 21109304JF KANKARA KATSINA 20 ABUBAKAR ABDULRASHID 21106628IA JIBIA KATSINA 21 BABANGIDA MU'AZU ALMUSTAPHA 21108659JA KATSINA KATSINA 22 MUSA SALAHUDDEEN 21109378BA BAKORI KATSINA 23 ZAINAB IMAM MUHAMMAD 21128654FF KANKIA KATSINA 24 IDRIS ABDULLAHI 21109387GA MATAZU KATSINA 25 DAHIRU IS'HAQ 21136785GA KATSINA KATSINA 26 DAHIRU ABUBAKAR RAFUKKA 21107101JA KATSINA KATSINA 27 AMINU IBRAHIM 21108454HA KATSINA KATSINA 28 IBRAHIM FATIMA 21118613AF KATSINA KATSINA 29 BISHIR YSUF SHEHU 21115880IF KATSINA KATSINA 30 TANIMU ABDULGANIYU HASSAN 22198263DF RIMI KATSINA 31 ABBAS -

Mise En Page 1

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. National Human Development Report Inclusive growth and human development The role of human capital SUMMARY I PREFACE III ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS VI HIGHLIGHTS IX Y BOX IX FIGURES X TABLES XII R EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XIV GENERAL INTRODUCTION : AN OVERVIEW 1 CHAPTER 1: UNDERSTANDING THE LINKS BETWEEN ECONOMIC GROWTH AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 7 a 1.1. THE CONCEPT OF ECONOMIC GROWTH 7 1.2. THE CONCEPT OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: OVERVIEW AND TRENDS 11 1.3. THE LINK BETWEEN GROWTH AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 14 m CHAPTER 2: THE ROLE OF HUMAN CAPITAL IN ECONOMIC GROWTH 16 2.1. THE CONCEPT OF HUMAN CAPITAL: CONTENT AND FACETS 16 2.2. STYLISIZED FACTS OF HUMAN CAPITAL IN CAMEROON 25 2.3. THE LINK BETWEEN HUMAN CAPITAL AND ECONOMIC GROWTH IN CAMEROON: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS 45 m CHAPTER 3: HUMAN CAPITAL AT VARIOUS STEPS TO ECONOMIC GROWTH IN CAMEROON 47 3.1. FIRST PHASE (1960-1986): A STRONG AND REDISTRIBUTED ECONOMIC GROWTH 48 u 3.2. SECOND PHASE (1987-1994): ECONOMIC DOWNTURN AND DEGRADATION OF HUMAN CAPITAL 50 3.3. THIRD PHASE (1995-2012): GROWTH RECOVERY AND POVERTY REDUCTION WITH IMPROVMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 53 S CHAPTER 4: ECONOMIC GROWTH PROSPECTS AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 66 4.1 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK OF CAMEROON BY 2020 66 4.2. EVOLUTION AND OVERALL PUBLIC EXPENDITURE IN TERMS OF HUMAN CAPITAL 69 4.3. GROWTH SIMULATION MODEL ON HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 72 4.4. IMPACT OF ECONOMIC GROWTH ON HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: BASELINE SCENARIO 73 4.5. ALTERNATIVE SCENARIOS 75 CHAPTER 5: SOCIO-ECONOMIC RECOMMENDATIONS 81 5.1.