Rush Common & Brixton Hill Conservation Area Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Freehold Development Site with Planning Permission for 5 Apartments View More Information

CGI of proposed Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Freehold development site with planning permission for 5 apartments View more information... Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Home Description Location Planning Terms View all of our instructions here... III III • Vacant freehold plot • Sold with planning permission for 5 apartments • Contemporary 3 storey block • Well-located close by to Crystal Palace ‘triangle’ and Railway Station • OIEO £950,000 F/H DESCRIPTION An opportunity to acquire a freehold development site sold with planning permission for the erection for a 3 storey block comprising 5 apartments (2 x studio, 2 x 2 bed & 1 x 3 bed). LOCATION Positioned on Beardell Street the property is located in the heart of affluent Crystal Palace town centre directly adjacent to the popular Crystal Palace ‘triangle’ which offers an array of independent shops, restaurants and bars mixed in with typical high street amenities. In terms of transport, the property is located 0.5 miles away from Crystal Palace Station which provides commuters with National Rail services to London Bridge, London Victoria, West Croydon, and Beckenham Junction and London Overground services between Highbury and Islington (via New Cross) and Whitechapel. E: [email protected] W: acorncommercial.co.uk 120 Bermondsey Street, 1 Sherman Road, London SE1 3TX Bromley, Kent BR1 3JH T: 020 7089 6555 T: 020 8315 5454 Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Home Description Location Planning Terms View all of our instructions here... III III PLANNING The property has been granted planning permission by Lambeth Council (subject to S106 agreement which has now been agreed) for the ‘Erection of 3 storey building plus basement including a front lightwell to provide 5 residential units, together with provision of cycle stores, refuse/recycling storages and private gardens.’ Under ref: 18/00001/FUL. -

Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Subject Guide 1 – Records Relating to Inclosure Issue no. 19 July 2020 Contents Introduction 1 Organisation of List 2 Alphabetical List of Townships 2 A 2 B 2 C 3 D 4 E 4 F 4 G 4 H 5 I 5 K 5 L 5 M 6 N 6 O 6 R 6 S 7 T 7 U 8 W 8 Introduction Inclosure (occasionally spelled “enclosure”) refers to a reorganisation of scattered land holdings by mutual agreement of the owners. Much inclosure of Common Land, Open Fields and Moor Land (or Waste), formerly farmed collectively by the residents on behalf of the Lord of the Manor, had taken place by the 18th century, but the uplands of County Durham remained largely unenclosed. Inclosures, to consolidate land-holdings, divide the land (into Allotments) and fence it off from other usage, could be made under a Private Act of Parliament or by general agreement of the landowners concerned. In the latter case the Agreement would be Enrolled as a Decree at the Court of Chancery in Durham and/or lodged with the Clerk of the Peace, the senior government officer in the County, so may be preserved in Quarter Sessions records. In the case of Parliamentary Enclosure a Local Bill would be put before Parliament which would pass it into law as an Inclosure Act. The Acts appointed Commissioners to survey the area concerned and determine its distribution as a published Inclosure Award. -

Lambeth College

Further Education Commissioner assessment summary Lambeth College October 2016 Contents Assessment 3 Background 3 Assessment Methodology 4 The Role, Composition and Operation of the Board 4 The Clerk to the Corporation 4 The Executive Team 5 The Qualify of Provision 5 Student Numbers 5 The College's Financial Position 6 Financial Forecasts beyond 2015/2016 6 Capital Developments 6 Financial Oversight by the Board 6 Budget-setting Arrangements 7 Financial Reporting 7 Audit 7 Conclusions 7 Recommendations 8 2 Assessment Background The London Borough of Lambeth is the second largest inner London Borough with a population of 322,000 (2015 estimate). It has experienced rapid population growth, increasing by over 50,000 in the last 10 years up until 2015. There are five key town centers: Brixton, Clapham and Stockwell, North Lambeth (Waterloo, Vauxhall, Kennington), and Norwood and Streatham. Lambeth is the 5th most deprived Borough in London. One in five of the borough’s residents work in jobs that pay below the London Living Wage. This is reflected by the fact that nearly one in four (24%) young people live in families who receive tax credits. Major regeneration developments and improvements are underway for Waterloo and Vauxhall and the Nine Elms Regeneration project which will drive the transformation of these areas. Lambeth College has three main campuses in the borough, based in Clapham, Brixton and Vauxhall. Approximately a quarter of the student cohort in any given academic year are 16‐18 learners. In addition to this, there is also a significantly growing proportion of 16-18 learners on Apprenticeship programmes, moderate numbers on workplace‐training provision for employers and school link programmes which are offered to relatively smaller learner volumes. -

Issue 193 Dec 2005/Jan 2006 £1.00

CAATnews 75% OF ARMS DEALS WOULD NOT HAVE HAPPENED WITHOUT OUR HELP Issue 193 11 Goodwin Street, London N4 3HQ Dec 2005/Jan 2006 Tel: 020 7281 0297 Fax: 020 7281 4369 £1.00 Email: [email protected] Website: www.caat.org.uk CAATnews IN THIS ISSUE... Editor Melanie Jarman [email protected] Legal Consultant Glen Reynolds Proofreader Rachel Vaughan Design Richie Andrew Contributors Bristol CAAT, Kathryn Busby, Beccie D’Cunha, Ann Feltham, Nicholas Gilby, Anna Jones, Mike Lewis, James O’Nions, Ian Prichard, South Essex CAAT. Thank you also to our dedicated team of CAATnews stuffers. Printed by Russell Press on 100% recycled paper using only post consumer de-inked waste. Copy deadline for the next issue is 12 January 2006. We shall be posting it the week beginning 26 January 2006. Content of most website references are also available in print – contact CAAT National Gathering – see page 6 PATRICK DELANEY the CAAT office. Contributors to CAATnews express Countdown to DESO 3 their own opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of CAAT as an organisation. Contributors retain Arms Trade Shorts 4–5 copyright of all work used. CAAT was set up in 1974 and is a broad coalition of groups and News and updates 6 individuals working for the reduction and ultimate abolition of the Local campaign news and views 7 international arms trade, together with progressive demilitarisation within arms-producing countries. Cover story: DESO 8–9 Campaign Against Arms Trade 11 Goodwin Street, London N4 3HQ Feature: Arms trade treaty 10 tel: 020 7281 0297 fax: 020 7281 4369 email: [email protected] Reed campaign 11 web: www.caat.org.uk If you use Charities Aid Foundation cheques and would like to help TREAT Parliamentary 12 (Trust for Research and Education on Arms Trade), please send CAF Clean investment campaign 13 cheques, payable to TREAT, to the office. -

Demography Factsheet

Demography factsheet: Lambeth: - “a diverse and changing population” May 2017 Key facts: This profile provides a snapshot of the population of Lambeth 4,590 births (2015) Lambeth resident population 2016 - 327,582 1,440 deaths (2015) Large proportion - 5th most densely (44%) are young adults, populated local authority age 20-39 years in England and Wales Small proportion – 31% of population (8%) are older adults, live in areas of age 65 plus high deprivation Ethnically diverse: 44th most deprived 3 in 5 describe their local authority in ethnicity as other than England (of 326) white British 9th most deprived High turnover: local authority in 40,000 people leave the London borough, and over 40,000 others move to the borough every year One third of families with children are in receipt of benefits Copies of this, and other public health profiles are available from the Lambeth JSNA website: www.lambeth.gov.uk Population structure by age and sex Source: GLA, 2015 based housing-led pop. projections, Feb '17 release (Lambeth & Gr.London); ONS 2014 based SNPP (England) Copies of this, and other public health profiles are available from the Lambeth JSNA website: www.lambeth.gov.uk Population structure by ward • Larkhall has the greatest ward • Bishop’s has the lowest ward population (19,133) population (10,066) *Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding Source: GLA, 2015 based housing-led pop. projections, Feb '17 release (Lambeth & Gr.London); ONS 2014 based SNPP (England) Copies of this, and other public health profiles are available from the Lambeth JSNA website: www.lambeth.gov.uk Population Structure by ward The table shows the count of individuals within each age band for every Lambeth ward. -

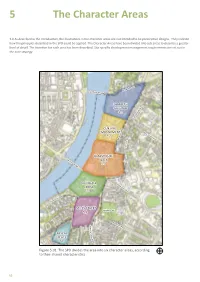

The Character Areas 5

5 The Character Areas 5.0 As described in the Introduction, the illustrations in the character areas are not intended to be prescriptive designs. They indicate how the principles described in the SPD could be applied. The Character Areas have been divided into sub areas to describe a greater level of detail. The intention for each area has been described. Site specific development management requirements are set out in the core strategy. Lambeth Road Lambeth Bridge LAMBETH GATEWAY 5.1 Lambeth Walk CENTRAL embankment Black Prince Road 5.2 Vauxhall Walk Tyers Street GLASSHOUSE Vauxhall Bridge walk 5.3 VauxHALL Harleyford Road Cross 5.4 Nine Elms Lane miles street Vauxhall Park 5.5 Fentiman Road South South Lambet pascal place h R 5.6 oad Figure 5.01. The SPD divides the area into six character areas, according to their shared characteristics 52 5 Figure 5.02. The vision for Vauxhall 53 5.1 Lambeth Gateway Existing Illustrative Road Road Lambeth Palace Lambeth Palace Lambeth Road Lambeth Road Pratt walk Pratt walk Old Paradise Street Old Paradise Street Paradise Gardens Paradise Gardens Street Whitgift Street Newport Street Albert Embankment Newport Street Whitgift Street Lambeth Walk Lambeth High Lambeth Walk Albert Embankment Lambeth High Street Black Prince Road Black Prince Road Fig. 5.10 Fig. 5.11 0 50 Existing Proposed Lambeth Gateway 5.10 Forming the entrance to Vauxhall, the Lambeth Gateway 5.12 The Lambeth Gateway will include: plays a critical role in drawing people from Lambeth Palace • Around 340 new homes and provide at least 630 new Road, Lambeth Road and Lambeth Bridge into the area. -

'Common Rights' - What Are They?

'Common Rights' - What are they? An investigation into rights of passage and rights of land use (or rights of common) Alan Shelley PG Dissertation in Landscape Architecture Cheltenham & Gloucester College of Higher Education April2000 Abstract There is a level of confusion relating to the expression 'common' when describing 'common rights'. What is 'common'? Common is a word which describes sharing or 'that affecting all alike'. Our 'common humanity' may be a term used to describe people in general. When we refer to something 'common' we are often saying, or implying, it is 'ordinary' or as normal. Mankind, in its earliest civilisation formed societies, usually of a family tribe, that expanded. Society is principled on community. What are 'rights'? Rights are generally agreed practices. Most often they are considered ethically, to be moral, just, correct and true. They may even be perceived, in some cases, to include duty. The evolution of mankind and society has its origins in the land. Generally speaking common rights have come from land-lore (the use of land). Conflicts have evolved between customs and the statutory rights of common people (the people of the commons). This has been influenced by Church (Canonical) law, from Roman formation, statutory enclosures of land and the corporation of local government. Privilege, has allowed 'freemen', by various customs, certain advantages over the general populace, or 'common people'. Unfortunately, the term no longer describes a relationship of such people with the land, but to their nationhood. Contents Page Common Rights - What are they?................................................................................ 1 Rights of Common ...................................................................................................... 4 Woods and wood pasture ............................................................................................ -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW OF GREATER LONDON, THE LONDON BOROUGHS AND THE CITY OF LONDON THE BOUNDARIES OF THE LONDON BOROUGHS OF BROMLEY, CROYDON, LAMBETH, LEWISHAM, AND SOUTHWARK IN THE VICINITY OF CRYSTAL PALACE. REPORT NO. 632 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO 632 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN SIR GEOFFREY ELLERTON CMG MBE MEMBERS MR K F J ENNALS CB MR G R PRENTICE MRS H R V SARKANY MR C W SMITH PROFESSOR K YOUNG SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF GREATER LONDON, THE LONDON BOROUGHS AND THE CITY OF LONDON THE BOUNDARIES OF THE LONDON BOROUGHS OF BROMLEY, CROYDON, LAMBETH, LEWI SHAM AND SODTHWARK IN THE VICINITY OF CRYSTAL PALACE COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT AND PROPOSALS INTRODUCTION 1. On 1 April 1987 we announced the start of the review of Greater London, the London Boroughs and the City of London, as part of the programme of reviews we are required to undertake by virtue of section 48(1) of the Local Government Act 1972. We wrote to each of the local authorities concerned. 2. Copies of our letter were sent to the appropriate county, district and parish councils bordering Greater London; the local authority associations; Members of Parliament with constituency interests; and the headquarters of the main political parties. In addition, copies were sent to the Metropolitan Police and to those government departments, regional health authorities, electricity, gas and water undertakings which might have an interest, as well as local television and radio stations serving the Greater London area and to a number of other interested persons and organisations. -

Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History

U N I V E R S I T Y O F O X F O R D Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History Number 26, Nov. 1998 AN ARDUOUS AND UNPROFITABLE UNDERTAKING: THE ENCLOSURE OF STANTON HARCOURT, OXFORDSHIRE1 DAVID STEAD Nuffield College, University of Oxford 1 I owe much to criticism and suggestion from Simon Board, Tracy Dennison, Charles Feinstein, Michael Havinden, Avner Offer, and Leigh Shaw-Taylor. The paper also benefited from comments at the Economic and Social History Graduate Workshop, Oxford University, and my thanks to the participants. None of these good people are implicated in the views expressed here. For efficient assistance with archival enquiries, I am grateful to the staff at the Bodleian Library, Oxford University (hereafter Bodl.), Oxfordshire Archives (OA), the House of Lords Record Office (HLRO), West Sussex Record Office (WSRO), and the Department of Archives and Manuscripts, Reading University. I thank Michael Havinden, John Walton, and the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College for permitting citation of material. Financial assistance from the Economic and Social Research Council is gratefully acknowledged. Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History are edited by: James Foreman-Peck St. Antony’s College, Oxford, OX2 6JF Jane Humphries All Souls College, Oxford OX1 4AL Susannah Morris Nuffield College, Oxford OX1 1NF Avner Offer Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF David Stead Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF papers may be obtained by writing to Avner Offer, Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF email:[email protected] 2 Abstract This paper provides a case study of the parliamentary enclosure of Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire. -

The Co-Operative Council

The Co-operative Council Sharing power: A new settlement between citizens and the state Lambeth’s proposal to become a Co-operative Council has generated a striking amount of passion, interest and debate over the past year. This new approach to public service delivery aims to reshape the settlement between citizens and the state by handing more power to local people so that a real partnership of equals can emerge. I believe the huge level of interest in our ideas both locally and nationally is driven by a genuine desire to find new and better ways to deliver public services in the 21st century. Although we publish this report at a time of unprecedented Government cuts in funding for local services, ours is not a cuts-driven agenda. I believe that if we do not make this change then the future of public services will be much more uncertain. The Co-operative Council draws inspiration from the values of fairness, accountability and responsibility that have driven progressive politics in this country for centuries. It is about putting the resources of the state at the disposal of citizens so that they can take control of the services they receive and the places where they live. More than just volunteering, it is about finding new ways in which citizens can participate in the decisions that affect their lives. The Co-operative Council is also not just about changing the council, it is about building more co-operative communities and realising that, for too long, the council has stood in the way rather than supported this development. -

Trams in Brixton 1870 - 1951

TRAMS IN BRIXTON 1870 - 1951 Horse Trams Two Acts of Parliament, passed in 1869 and 1870, empowered the Metropolitan Street Tramways Company to construct tramways from the Lambeth end of Westminster Bridge to Brixton and to Clapham. The company got to work quickly; they lost no time in laying down double tracks with rails level with the surface of the road. 2 May 1870 was an important day in Brixton's history. It was the day when the first authorised tramcars operated in London. 1 The new trams ran that day from the Horns Tavern in Kennington Road and along Brixton Road as far as its junction with Stockwell Road. The smart blue tramcars were hauled by two horses. Cars seated 22 persons inside and 24 on the open top deck. The passengers inside sat on red velvet cushions. For top deck passengers were two wooden benches running the length of the tram; these passengers faced outwards. Trams ran every five minutes. The normal fare was a penny a mile but Parliament had required special trams to be run for workmen in the morning and evenings at a halfpenny a mile.2 As soon as the 1870 Act was passed more track laying was rushed on with, and by the end of 1870 trams were in service from the Lambeth end of Westminster Bridge to St Matthew's church, Brixton, and another line ran along Clapham Road to the Swan at Stockwell. During 1871 tramcars had reached the Plough at Clapham, and the Brixton Line had been extended to the junction of Brixton Water Lane. -

Proposed Controlled Parking Zone

Proposed Controlled Parking Zone Zone F – Brixton Hill East l Implementation Issue Date: 31 JULY 2017 Dear Resident/Business The purpose of this leaflet is to let you know the outcome of the statutory consultation carried out in March/April 2017, and to inform you of the Council’s decision on the proposed ‘F’ Controlled Parking Zone (CPZ). All representations received along with officers’ recommendations were presented in a report to be considered by the Council. After careful consideration a decision has been made to proceed with the implementation of the proposed ‘F’ CPZ. The report, the Council’s decision and plans detailing the proposals can be viewed online at www.lambeth.gov.uk/bhcpz. What Happens Next The final Traffic Management Orders (TMOs), which allows the restrictions to be implemented and administered, will be published in the London Gazette and the local newspaper (Lambeth Weekender) shortly. Notices will also be placed on lamp columns in the affected area. Finally, we would like to thank you for your participation in the consultation process and for your feedback. Implementation Works The lining and signing works will be carried out by our contractor CVU (Colas VolkerHighways URS) on behalf of the Council. It is anticipated that the works for the entire area, which includes the new Brixton Hill West Zone ‘D’, Brixton Hill East Zone ‘F’, Tulse Hill Zone ‘H’ extension, Clapham Zone ‘L’ extension and Brixton Hill Zone ‘Q’ extension will start the week commencing 7 August 2017 for a period of 4-6 weeks. The works for your (Zone D) area should take 10 - 15 working days to complete, weather permitting.