An Examination of Male to Female Transgender Sex Workers' Experiences Within the Health Care and Social Service Systems in San Francisco, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transgender Representation on American Narrative Television from 2004-2014

TRANSJACKING TELEVISION: TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION ON AMERICAN NARRATIVE TELEVISION FROM 2004-2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Kelly K. Ryan May 2021 Examining Committee Members: Jan Fernback, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Ron Becker, External Member, Miami University ABSTRACT This study considers the case of representation of transgender people and issues on American fictional television from 2004 to 2014, a period which represents a steady surge in transgender television characters relative to what came before, and prefigures a more recent burgeoning of transgender characters since 2014. The study thus positions the period of analysis as an historical period in the changing representation of transgender characters. A discourse analysis is employed that not only assesses the way that transgender characters have been represented, but contextualizes American fictional television depictions of transgender people within the broader sociopolitical landscape in which those depictions have emerged and which they likely inform. Television representations and the social milieu in which they are situated are considered as parallel, mutually informing discourses, including the ways in which those representations have been engaged discursively through reviews, news coverage and, in some cases, blogs. ii To Desmond, Oonagh and Eamonn For everything. And to my mother, Elaine Keisling, Who would have read the whole thing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the research and writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance, and therefore offer many thanks. To my Dissertation Chair, Jan Fernback, whose feedback on my writing and continued support and encouragement were invaluable to the completion of this project. -

Barriers, Boundaries, and Borders: an Investigation Into Transgender Experiences

Title Page Barriers, Boundaries, and Borders: An Investigation into Transgender Experiences within Medical Institutions by Madison T. Scull Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2019 Submitted to the Undergraduate Faculty of University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Membership Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE This thesis was presented by Madison T. Scull It was defended on April 5, 2019 and approved by Julie Beaulieu, PhD, Lecturer, University of Pittsburgh Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program Lisa Brush, PhD, Professor, University of Pittsburgh Department of Sociology Natalie Kouri-Towe, PhD, Assistant Professor, Concordia University Simone de Beauvoir Institute & Womens Studies Thesis Advisor: Lester Olson, PhD, Chair and Professor, University of Pittsburgh Department of Communication ii Copyright © by Madison T. Scull 2019 iii Abstract Barriers, Boundaries, and Borders: An Investigation into Transgender Experiences within Medical Institutions Madison T. Scull, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2019 As a population that has been often dismissed, neglected, discriminated against, and abused by medical institutions, the relationship between the transgender community and medicine has remained shrouded in silence until recent history. As a result of being forced to contend with transphobia, violence, and erasure, the transgender community in the United States suffers from tangible health -

The Experiences of Transgender Female Sex Workers Within Their Families, Occupation, and the Healthcare System

THE EXPERIENCES OF TRANSGENDER FEMALE SEX WORKERS WITHIN THEIR FAMILIES, OCCUPATION, AND THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM. SHELLEY ANN VICKERMAN Degree: M.A. Research Psychology Department: Psychology Supervisor: Mr Umesh Bawa Co-Supervisor: Prof Brian Eduard van Wyk A mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Arts in Psychology in the Department of Psychology University of the Western Cape Bellville 2018. Keywords: Transgender; sex work; HIV; violence; discrimination; stigma; poverty; heteronormativity; gender; intersectional feminism http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ Abstract There is a dearth of scholarly literature surrounding transgender female sex workers (TFSW) within South Africa. Their voices are often marginalised and not adequately heard in the literature and in a society that generally views gender as a fundamental element of the self, determining their subject positions against binaried heteronormative gender ideals. This process of the ‘othering’ of TFSW, is exacerbated by the moralistic judging of their occupation of sex work. This has left many TFSWs vulnerable to emotional abuse such as being socially stigmatised, discriminated against and socially isolated. The literature further echoes vulnerability to physical violence, such as hate crimes, rape, heightened HIV infection, homelessness, police brutality and murder. The current study aimed to explore the subjective experiences of TFSW within their families, occupations and the healthcare system within the Cape Town metropole, South Africa. The study was framed within an intersectional feminist epistemological position, highlighting intersecting identities that marginalise groups of people. Informant driven sampling was used in the case of this study where a total of eleven participants were individually interviewed using a semi-structed approach – interviews ranged from 35-90 minutes. -

Violence, Belonging, and Potentiality in Transgender Latina Sexual Economies Andrea Bolivar Washington University in St

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2018 We are a Fantasia: Violence, Belonging, and Potentiality in Transgender Latina Sexual Economies Andrea Bolivar Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bolivar, Andrea, "We are a Fantasia: Violence, Belonging, and Potentiality in Transgender Latina Sexual Economies" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1512. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1512 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Anthropology Dissertation Examination Committee: Shanti Parikh, Chair Bret Gustafson, Co-Chair Rebecca Lester Jeffrey McCune Gina Pérez “We Are a Fantasía: Violence, Belonging, and Potentiality in Transgender Latina -

The 11 Annual Transgender Day of Remembrance

The 11th Annual Transgender Day of Remembrance The Transgender Day of Remembrance was set aside to memorialize those who were killed due to anti-transgender hatred or prejudice. The event is held in November to honor Rita Hester, whose murder on November 28, 1998 kicked off the “Remembering Our Dead” web project and a San Francisco candlelight vigil in 1999. Rita Hester’s murder – like most anti-transgender murder cases – has yet to be solved. Every November, we at UCR recognize and honor these individuals with this poster display. To date, there are more than 400 documented cases of individuals dying because of violence against transgender people. For additional information on the Transgender Day of Remembrance or transgender identities check out some of these websites: www.transgenderdor.org www.gpac.org www.transgenderlaw.org www.nctequality.org www.imatyfa.org www.trans-academics.org For additional information at UCR, come into the LGBT Resource Center in 245 Costo Hall or visit www.out.ucr.edu to check out these resources: Trans/Intersex Allies Program Transgender-themed books, videos & DVDs – Available for check out by students, faculty, and staff. The Annual Transgender Day of Remembrance We set aside this day to memorialize those have been killed due to anti-transgender hatred or prejudice. Although not every person represented during the Day of Remembrance self-identified as transgender — that is, as a transsexual, cross-dresser, or otherwise gender- variant — each was a victim of violence based on bias against transgender people. The Transgender Day of Remembrance raises public awareness of hate crimes against transgender people, and publicly mourns and honors the lives of our brothers and sisters who might otherwise be forgotten. -

“We Need a Law for Liberation” Gender, Sexuality, and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey

“We Need a Law for Liberation” Gender, Sexuality, and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-316-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2008 1-56432-316-1 “We Need a Law for Liberation” Gender, Sexuality, and Human Rights in a Changing Turkey Glossary of Key Terms........................................................................................................ 1 I. Summary...................................................................................................................... 3 Visibility and Violence .................................................................................................... 3 Key Recommendations ..................................................................................................10 Methods........................................................................................................................12 II. Background: Imposing Gender: Identities and Histories..............................................14 III. Living in Fear: Harassment and Abuses against Gay Men ........................................... -

Shadow Report to the Cedaw Committee on the Situation of Female Sex Workers in Mexico 2018

SHADOW REPORT TO THE CEDAW COMMITTEE ON THE SITUATION OF FEMALE SEX WORKERS IN MEXICO 2018 INTRODUCTION Asociación en Pro Apoyo a Servidores (APROASE A.C.), together with Tamaulipas VIHda Trans, A.C., members of the Global Network of Sex Work Project (NSWP) and la Plataforma Latinoamericana de Personas que ejercen el Trabajo Sexual (PLAPERTS) developed this Shadow Report to highlight the situation of female sex workers in Mexico and the diverse forms of discrimination they face before the CEDAW Committee. APROASE, A.C. is an organization with 30 years of experience advocating for the human rights of female sex workers, constituted, operated and directed by and for sex workers in Mexico, with national and international reach through human rights projects. Tamaulipas VIHda Trans, operating mainly in the north of the country, is an organization that has more than 20 years of experience advocating for the rights of transgender sex workers, with experience in regional projects in Mexico. METHODOLOGY The objective of this report is to inform the CEDAW committee about the different forms of violence, stigma and discrimination that we, cisgender and transgender female sex workers (TS) in Mexico experience. The CEDAW articles selected to reflect the violence cisgender and transgender female sex workers in Mexico face are the following: Article 1: Discrimination Article 3: Fulfillment of basic rights and fundamental freedoms Article 6: Trafficking and exploitation of prostitution Article 12: Health and family planning services (Right to Health) Article 15: Equality before the law A questionnaire, based on the aforementioned articles, was developed and used to conduct focus groups1 with female sex workers. -

“MY LIFE IS TOO DARK to SEE the LIGHT” a Survey of the Living Conditions of Transgender Female Sex Workers in Beijing and Shanghai

“MY LIFE IS TOO DARK TO SEE THE LIGHT” A Survey of the Living Conditions of Transgender Female Sex Workers in Beijing and Shanghai C Based on research in Beijing and Shanghai, China this report focuses on the daily life, working conditions, access to services, and legal frameworks for transgender female sex workers in China. Transgender female sex workers face a broad array of discrimination in social and policy frameworks, preventing this highly marginalized group’s access to a wide spectrum of services and legal protections. They experience amplifed stigma due to both their gender identity and their profession. Isolated and often humiliated when seeking public services, particularly in health care settings, has also led many to self-medicate and engage in dangerous transitioning practices, including on self-administered hormone use. In China, transgender people do not necessarily face outright legal penalties, but the absence of non- discrimination laws and lack of enforcement of overarching policies on non-discriminatory access to healthcare and HIV related services, means they are left without efective protection. As sex work is illegal in China, transgender sex workers are further oppressed by the police and, due to social and other factors, engage in high risk activities that put them at increased risk of HIV and STD infection. The research for this report illuminates that the community of female presenting sex workers is very complex and includes men who have sex with men, transgender individuals, and transsexuals. Their vulnerabilities to HIV and their varied health needs need to be carefully assessed, strategically targeted, and addressed. As China is in the process of drafting a new HIV/AIDS action plan for 2016-2020, now is a good opportunity to develop a specifc strategy on HIV prevention and care for the transgender community. -

Mama Cash's Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 Contents 04 Because feminist 43 Programme partnerships activism works • Count Me In! Consortium • An introduction from • Global Alliance for Green and Mama Cash’s Board Co-Chairs Gender Action and Executive Director • CreatEquality 06 Grantmaking and 49 Learning, monitoring accompaniment and evaluation • Body portfolio 50 Partnerships and • Money portfolio communications • Voice portfolio • Opportunity portfolio • Accompaniment portfolio 53 Mama Cash’s • Spark portfolio contribution to change 33 Strengthening • Highlights of our 2018 goals women’s funds and accomplishments 37 Influencing the 56 Mama Cash’s donor community contributors in 2018 38 Special initiative: 57 Annual accounts 2018 Red Umbrella Fund • Organisational report • Board report • Financial report 95 Credits Annual Report 2018 Contents — 2 Since 1983, Mama Cash has awarded €66,294,955 to women’s, girls’, trans and intersex people’s groups worldwide. we have a vision ... Every woman, girl, trans and intersex person has the power and resources to participate fully and equally in creating a peaceful, just and sustainable world. we are on a mission ... Courageous women’s, girls’, trans and intersex grants to women’s, girls’, trans and intersex people’s people’s human rights organisations worldwide need human rights organisations, and helps to build the funding and supportive networks in order to grow and partnerships and networks needed to successfully transform their communities. Mama Cash mobilises defend and advance women’s, girls’, trans and resources from individuals and institutions, makes intersex people’s human rights globally. our values lead the way... Embracing diversity in our organisation Committed to being accountable, to evaluating and and among our partners. -

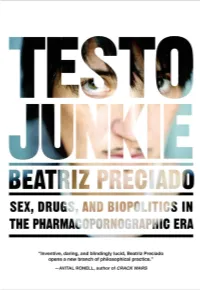

Testo Junkie Is a Key Text to Comprehend the Deep Interconnectedness of Sex and Drugs Today.”

“ Testo Junkie is a wild ride. Preciado leaves the identity politics of taking T to others, and instead, in the tradition of William S. Burroughs, Kathy Acker, and Jean Genet, s/he conducts a wild textual experiment. The results are spectacular . The gendered body will never be the same again.” —JACK HALBERSTAM, author of THE QUEER ART OF FAILURE “ Beatriz Preciado’s brilliant book oscillates between high theory and the surging rush of testosterone. Flush with elegant theoretical formulations, lascivious sex nar- ratives, and astute histories of gender, Testo Junkie is a key text to comprehend the deep interconnectedness of sex and drugs today.” —JOSÉ ESTEBAN MUÑOZ, author of CRUISING UTOPIA “The ideas in Beatriz Preciado’s pornosophical gem are a thousand curious fingers slipped beneath the underpants of conventional thinking. Teach the sex scenes in your seminars, and read the flights of theory aloud to your latest lover amid a tangle of sweaty sheets.” —SUSAN STRYKER, author of THE TRANSGENDER STUDIES READER “ Testo Junkie is unlike anything I’ve ever read. Beatriz Preciado has produced a volume of work that goes far beyond memoir to create an entirely new way of understanding not only the history of sex, gender, and the body, but of life as we have come to know it. Powerful and disturbing in the most pleasurable way.” —DEL LAGRACE VOLCANO, author of FEMMES OF POWER “ Beatriz Preciado offers an exhilarating and sometimes shattering portrait of how gen- dershapesthewaysweliveandfuckandgrieveandfightandlove.Testo Junkie is a fearless chronicle of the gender revolution currently in progress. Anyone who has a gender—or has dispensed with one—should read this book.” —GAYLE SALAMON, author of ASSUMING A BODY “ Inventive, daring, and blindingly lucid, Beatriz Preciado opens a new branch of phil- osophical practice. -

Trans People in the Criminal Justice System

Trans People in the Criminal Justice System A guide for criminal justice personnel Joshua Mira Goldberg for the Women/Trans Dialogue Planning Committee, the Justice Institute of BC, and the Trans Alliance Society For further information or to order copies of this manual, contact: Shelley Rivkin Director, Centre for Leadership & Community Learning Justice Institute of BC 715 McBride Boulevard, New Westminster, BC V3L 5T4 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.jibc.bc.ca/clcl/ Trans Alliance Society c/o 1170 Bute St, Vancouver, BC V6E 1Z6 Tel: 604-684-9872 Ext. 2044 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.transalliancesociety.org Introduction Acknowledgments This project is a joint initiative of the Women/Trans Dialogue Planning Committee, the Justice Institute of BC, and Trans Alliance Society. As a collaborative effort that involved many communities, there are many people to thank. We thank the members of the Women/Trans Dialogue Planning Committee (W/TDPC) for their leadership in initiating this project. We particularly thank the members of the W/TDPC Project Advisory Team – WG Burnham, Joey Daly, Dean Dubick, Tracy Porteous, and Caroline White – for reviewing the material, providing suggestions and feedback, and otherwise overseeing the development of this information package. Our readers provided invaluable feedback on drafts of the guide, and we thank them (and, where applicable, the organizations they represent) for their efforts: WG Burnham (Trans Alliance Society, Trans/Action, and Women/Trans Dialogue Planning Committee), Monika Chappell (Youthquest!, Pacific DAWN, and December 9 Coalition), H. Aidean Diamond, Romham Padraig Gallacher, Emi Koyama (Community Board Chair, Survivor Project), and Aiyyana Maracle (independent artist and MFA candidate). -

The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers

BRIEFING PAPER The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global Action for Gay Men’s Health and Rights | BRIEFING PAPER | The Homophobia and Transphobia Experienced by LGBT Sex Workers | NSWP Global Network of Sex Work Projects | MPact Global