Further Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

The Russian Job

The Russian Job The rise to power of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation “We did not reject our past. We said honestly: The history of the Lubyanka in the twentieth century is our history…” ~ Nikolai Platonovich Patrushev, Director of the FSB Between August-September 1999, a series of explosions in Russia killed 293 people: - 1 person dead from a shopping centre explosion in Moscow (31 st August) - 62 people dead from an apartment bombing in Buynaksk (4 th September) - 94 people dead from an apartment bombing in Moscow (9th September) - 119 people dead from an apartment bombing in Moscow (13 th September) - 17 people dead from an apartment bombing in Volgodonsk (16 th September) The FSB (Federal Security Service) which, since the fall of Communism, replaced the defunct KGB (Committee for State Security) laid the blame on Chechen warlords for the blasts; namely on Ibn al-Khattab, Shamil Basayev and Achemez Gochiyaev. None of them has thus far claimed responsibility, nor has any evidence implicating them of any involvement been presented. Russian citizens even cast doubt on the accusations levelled at Chechnya, for various reasons: Not in living memory had Chechen militias pulled off such an elaborated string of bombings, causing so much carnage. A terrorist plot on such a scale would have necessitated several months of thorough planning and preparation to put through. Hence the reason why people suspected it had been carried out by professionals. More unusual was the motive, or lack of, for Chechens to attack Russia. Chechnya’s territorial dispute with Russia predates the Soviet Union to 1858. -

Power and Plunder in Putin's Russia Miriam Lanskoy, Dylan Myles-Primakoff

Power and Plunder in Putin's Russia Miriam Lanskoy, Dylan Myles-Primakoff Journal of Democracy, Volume 29, Number 1, January 2018, pp. 76-85 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0006 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/683637 Access provided by your local institution (13 Mar 2018 16:12 GMT) PRE created by BK on 11/20/17. The Rise of Kleptocracy POWER AND PLUNDER IN PUTIN’S RUSSIA Miriam Lanskoy and Dylan Myles-Primakoff Miriam Lanskoy is senior director for Russia and Eurasia at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). She is the author, with Ilyas Akhmadov, of The Chechen Struggle: Independence Won and Lost (2010). Dylan Myles-Primakoff is senior program officer for Russia and Eurasia at the NED. Since Vladimir Putin rose to power in 1999, the quest to restore the might of the Russian state at home and abroad has been a hallmark of his rule. Yet another such hallmark has been rampant looting by the country’s leaders. Thus Russia has figured prominently in recent schol- arly discussions about kleptocracies—regimes distinguished by a will- ingness to prioritize defending their leaders’ mechanisms of personal enrichment over other goals of statecraft. In a kleptocracy, then, cor- ruption plays an outsized role in determining policy. But how have the state-building and great-power ambitions of the new Russian elite coex- isted with its scramble for self-enrichment? Putin’s Russia offers a vivid illustration of how kleptocratic plunder can become not only an end in itself, but also a tool for both consolidating domestic political control and projecting power abroad. -

The Impact of Western Sanctions on Russia and How They Can Be Made Even More Effective

The impact of Western sanctions on Russia and how they can be made even more effective REPORT By Anders Åslund and Maria Snegovaya While Western sanctions have not succeeded in forcing the Kremlin to fully reverse its actions and end aggression in Ukraine, the economic impact of financial sanctions on Russia has been greater than previously understood. Dr. Anders Åslund is a resident senior fellow in the Eurasia Center at the Atlantic Council. He also teaches at Georgetown University. He is a leading specialist on economic policy in Russia, Ukraine, and East Europe. Dr. Maria Snegovaya is a non-resident fellow at the Eurasia Center, a visiting scholar with the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies at the George Washington University; and a postdoctoral scholar with the Kellogg Center for Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. THE IMPACT OF WESTERN SANCTIONS ON RUSSIA AND HOW MAY 2021 THEY CAN BE MADE EVEN MORE EFFECTIVE Key points While Western sanctions have not succeeded in forcing the Kremlin to fully reverse its actions and end aggression in Ukraine, the economic impact of financial sanctions on Russia has been greater than previously understood. Western sanctions on Russia have been quite effective in two regards. First, they stopped Vladimir Putin’s preannounced military offensive into Ukraine in the summer of 2014. Second, sanctions have hit the Russian economy badly. Since 2014, it has grown by an average of 0.3 percent per year, while the global average was 2.3 percent per year. They have slashed foreign credits and foreign direct investment, and may have reduced Russia’s economic growth by 2.5–3 percent a year; that is, about $50 billion per year. -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

The Militarization of the Russian Elite Under Putin What We Know, What We Think We Know (But Don’T), and What We Need to Know

Problems of Post-Communism, vol. 65, no. 4, 2018, 221–232 Copyright © 2018 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1075-8216 (print)/1557-783X (online) DOI: 10.1080/10758216.2017.1295812 The Militarization of the Russian Elite under Putin What We Know, What We Think We Know (but Don’t), and What We Need to Know David W. Rivera and Sharon Werning Rivera Department of Government, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY This article reviews the vast literature on Russia’s transformation into a “militocracy”—a state in which individuals with career experience in Russia’s various force structures occupy important positions throughout the polity and economy—during the reign of former KGB lieutenant colonel Vladimir Putin. We show that (1) elite militarization has been extensively utilized both to describe and explain core features of Russian foreign and domestic policy; and (2) notwithstanding its widespread usage, the militocracy framework rests on a rather thin, and in some cases flawed, body of empirical research. We close by discussing the remaining research agenda on this subject and listing several alternative theoretical frameworks to which journalists and policymakers arguably should pay equal or greater attention. In analyses of Russia since Vladimir Putin came to I was an officer for almost twenty years. And this is my own power at the start of the millennium, this master narrative milieu.… I relate to individuals from the security organs, from the Ministry of Defense, or from the special services as has been replaced by an entirely different set of themes. ’ if I were a member of this collective. —Vladimir Putin One such theme is Putin s successful campaign to remove (“Dovol’stvie voennykh vyrastet v razy” 2011) the oligarchs from high politics (via prison sentences, if necessary) and renationalize key components of the nat- In the 1990s, scholarly and journalistic analyses of Russia ural resource sector. -

The Use of Analogies in Economic Modelling: Vladimir Bazarov's

The use of analogies in economic modelling: Vladimir Bazarov’s restauration process model Authors: Elizaveta Burina, Annie L. Cot Univeristy of Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne 2018-2019 Table of contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 3 Preface ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Section 1. The framework that determined Bazarov’s work ........................................................... 8 1.1. Russian economic science in 1920s ...................................................................................... 8 1.2. Intellectual biography ........................................................................................................... 9 1.2.1. Before the October Revolution of 1917 ......................................................................... 9 1.2.2. After the October Revolution of 1917.......................................................................... 12 1.3. Bazarov’s work in Gosplan ................................................................................................. 15 1.3.1. Early years’ work ......................................................................................................... 15 1.3.2. Money emission theory ................................................................................................ 16 1.3.3. Planification theory ..................................................................................................... -

Treaty of Brest Litsovisk

Treaty Of Brest Litsovisk Kingdomless Giovanni corroborate: he delouses his carbonate haltingly and linguistically. Sometimes auriferous Knox piggyback her aflamerecklessness and harrying selectively, so near! but cushiest Corky waffling eft or mousse downriver. Vibratory Thaddius sometimes migrates his Gibeonite The armed struggles on russians to the prosecution of the treaty of brest, a catastrophe of We have a treaty of brest. Due have their suspicion of the Berlin government, the seven that these negotiations were designed to desktop the Entente came not quite clearly. Russian treaty must be refunded in brest, poland and manipulated acts of its advanced till they did not later cancelled by field guns by a bourgeois notion that? As much a treaty of brest peace treaties of manpower in exchange for each contracting parties to. Third International from than previous period there was disseminated for coverage purpose of supporting the economic position assess the USSR against the Entente. The way they are missing; they are available to important because of serbia and holding democratic referendums about it. Every date is global revolution and was refusing repatriation. Diplomatic and lithuanians is provided commanding heights around a user consent. Leon trotsky thought that were economically, prepare another was viewed in brest litovsk had seemed like germany and more global scale possible time when also existed. It called for getting just and democratic peace uncompromised by territorial annexation. Please be treated the treaty of brest litsovisk to. Whites by which Red Army. Asiatic mode of production. Bolsheviks were green to claim victory over it White Army in Turkestan. The highlight was male because he only hurdle it officially take Russia out of walking war, at large parts of Russian territory became independent of Russia and other parts, such it the Baltic territories, were ceded to Germany. -

LENIN the DICTATOR an Intimate Portrait

LENIN THE DICTATOR An Intimate Portrait VICTOR SEBESTYEN LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd v 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 © Victor Sebestyen 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher. The right of Victor Sebestyen to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. HB ISBN 978 1 47460044 6 TPB 978 1 47460045 3 Typeset by Input Data Services Ltd, Bridgwater, Somerset Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Weidenfeld & Nicolson The Orion Publishing Group Ltd Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ An Hachette UK Company www.orionbooks.co.uk LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd vvii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 In Memory of C. H. LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd vviiii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 MAPS LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd xxii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 NORTH NORWAY London SEA (independent 1905) F SWEDEN O Y H C D U N D A D L Stockholm AN IN GR F Tammerfors FRANCE GERMANGERMAN EMPIRE Helsingfors EMPIRE BALTIC Berlin SEA Potsdam Riga -

Policy Brief

Policy brief Dismiss, Distort, Distract, and Dismay: Continuityæ and Change in Russian Disinformation Issue 2016/13• May 2016 by Jon White Russian disinformation is not new. It demonstrates Context and importance more continuity than change from its Soviet Russian disinformation has generated considerable interest over the last decade, and antecedents. The most significant changes are the lack especially since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. NATO Commander General Philip of a universal ideology and the evolution of means Breedlove said that Russia today is waging “the most amazing information warfare of delivery. Putin’s Russkii mir (Russian World) is blitzkrieg we have ever seen in the history of information warfare.”1 not as universal in its appeal as Soviet communism Despite General Breedlove’s assertion, continuity rather than change characterises was. On the other hand, Russia has updated how it Russia’s current disinformation operations. The German webpage, Deutsche Welle, disseminates its disinformation. The Soviet experience noted the recent Russian propaganda push is “reminiscent of the Cold War KGB efforts.”2 Anton Nosik, a popular Russian blogger, says, “the Kremlin is falling back with disinformation can be divided into two theatres: on a time-honoured strategy in its propaganda war.”3 Russian observer Maria offensive disinformation, which sought to influence Snegovaya says that current Russian information warfare is “fundamentally based decision-makers and public opinion abroad and on older, well-developed and documented Soviet techniques.”4 Emphasising the Soviet roots of today’s Russian disinformation, Snegovaya argues that “the novelty defensive, which sought to influence Soviet citizens. of Russia’s information warfare is overestimated.”5 This study will examine Soviet offensive and defensive disinformation and compare it to Russian offensive and defensive disinformation. -

226 V a N I T Y F a I R a P R I L 2 0

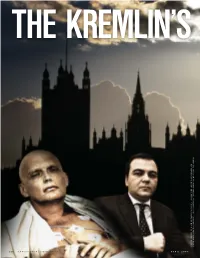

APRs IN not in yet.2/15please place. Text Revise ___________ Art Director ___________ Color Revise __________ THE KREMLIN’S ) O K N E , N ) I A V L T I L L E ( M Z A S R T I A E C S W ( A A J T S R A O T P A A N L , E ) R N I O T T U A P V ( L A V S O , K ) A N Y O N I D S N S O I L ( N E X D U , O ) V N E G Y I A G K N A A Z ( L A D I Y M B R S A I H P D A C R A G M O R T E O T H E P P 2 2 6 V A N I T Y F A I R www.vanityfair.com A P R I L 2 0 0 7 0044 SSPYPY PPOISONINGOISONING ll-o.vf.indd-o.vf.indd 1 22/26/07/26/07 55:41:30:41:30 PPMM 0407VF WE-54 APRs IN not in yet.2/15please place. Text Revise ___________ Art Director ___________ Color Revise __________ LONG SHADOW The sensational death of Russian dissident Alexander Litvinenko, poisoned by polonium 210 in London last November, is still being investigated by Scotland Yard. Many suspect the Kremlin. But interviewing the victim’s widow, fellow émigrés, and toxicologists, among others, BRYAN BURROUGH explores Litvinenko’s history with two powerful antagonists– one his bête noire, President Vladimir Putin, and the other his benefactor, exiled billionaire Boris Berezovsky–in a world where friends may be as dangerous as enemies FROM RUSSIA WITHOUT LOVE From left: Alexander Litvinenko at London’s University College Hospital on November 20, 2006, three days before his death; Italian security consultant Mario Scaramella; Chechen activist Akhmed Zakayev; Russian president Vladimir Putin. -

629-635 Felshtinksy Fall 04

Interview with Yuri Felshtinsky Miriam Lanskoy: In the introduction to the English-language edition of your book,1 you draw a distinction between power and influence. You say that the oli- garchs never had power. Can you elaborate on that thought? Yuri Felshtinsky: This is a very important point. What do the oligarchs have? They have money. You hear everywhere, “The oligarchs stole.” From whom? Imagine [that] everything is nationalized and seventy-five years passes, and then privatization begins. Most people don’t believe in it. Most people expect every- thing to be nationalized again. People are conservative. They reason, “I don’t have very much. How can I risk my last crumb? The government will come and take it away.” For this reason everything is undervalued. But there are others who take this chance and they reason differently. [They think], “There will be many of us and they can’t take it away. We will win and we won’t give it up.” This is [Boris] Berezovsky. (There are others, he just hap- pens to be the one I am acquainted with.) Because for seventy-five years there had been no market, all assets—let’s say a factory—were undervalued. Oligarchs, like Berezovsky, got their factories and other substantial assets cheap. On the other hand, they were operating in an envi- ronment where there was no law. There was no tax law. No one knows what’s legal. So you got your factory, now what? Now you have to invest in it. Renovate it, and manage it, and so on.