Texas Tech Law Review Shell Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Media Guide

2019 MEDIA GUIDE WWW.UTAHUTES.COM | @UTAHBASEBALL 1 2019 MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS TEAM INFORMATION Table of Contents 2 On May 23, 2018, the NCAA Committee on Infractions released its statement on the two Level Quick Facts 3 II violations sanctioned against the University of Utah baseball program. The violations are Covering the Utes/Media Information 4 related to impermissible practice and coaching activities by a non-coaching staff member. 2019 Schedule 5 2019 Roster/Pronunciation Guide 6-7 Starting in 2014-15, a sport-specific staff member, who was not designated as one of the four permissible coaches, engaged in impermissible on-field instruction. Specifically, the 2019 UTAH BASEBALL OUTLOOK staff member provided instruction to catchers, threw batting practice, and occasionally hit 2018 Season Outlook 9-10 baseballs to pitchers for fielding practice. This continued through the 2016-17 academic year. 2018 Opponents 11-13 As a result, the Utah baseball program exceeded the number of permissible coaches. UTAH BASEBALL COACHING STAFF After initiating an internal investigation, Utah turned over information to the NCAA. The Head Coach Bill Kinneberg 15-17 institution and the NCAA collaborated to finalize the investigation. Utah self-imposed three Associate Head Coach Mike Crawfod 18 penalties, which include: a $5,000 financial penalty, a reduction in countable athletically Assistant Coach Jay Brossman 19 related activities for the 2018 baseball season, and a suspension of the head coach for the Director of Operations Sydney Jones 20 first 25% of the 2018 baseball season. Volunteer Assistant Parker Guinn 20 Utah Athletic Administration 20 In addition to the aforementioned penalties, the NCAA applied a one-year probationary period and imposed public reprimand and censure. -

The University of Utah

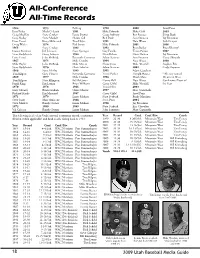

All-Conference All-Time Records 1964 1973 Ed Iorg 1990 2000 Jared Pena Jerry Fisher Mark Colerick 1981 Mike Edwards Mike Goff 2005 Craig MacKay Steve Cowley Lance Brewer Craig Sudbury Brit Pannier Doug Beck Gary Shelby Steve Marlow Shawn Gill Rob Beck Sam Swenson Jay Brossman Dave Varvel Kerry Milkovich Tim Hayes 1991 Nate Weese Josh Cooper Doug Wasko 1974 Phil Strom Mike Edwards 2001 2006 1965 Steve Cowley 1982 1992 Ryan Bailey Ryan Khoury* Duane Freeman Jeff Johnson Steve Springer Guy Fowlks Travis Palmer 2007 Steve Radulovich Gerry LeFavor 1984 Clint Kelson Chris Shelton Jay Brossman Dave Varvel John McBride Fernando Carmona Adam Sessions Sam Swenson Corey Shimada 1967 1975 Mike Dandos 1994 Nate Weese 2008 Mike Beyler John McBride Mike Moore Shane Jones Mike Westfall Stephen Fife Steve Radulovich 1976 Chris Schultis Adam Sessions 2002 Cody Guymon 1968 Scott Moffitt 1985 1995 Adam Castelton Tom Kilgore Gary Vincent Fernando Carmona Travis Parker Donald Hawes * Khoury named 1969 1977 Mike Dandos 1996 Mitch Maio Mountain West Tom Kilgore Nate Ellington Ed McCarter Danny Bell Nate Weese Conference Player of Frank King Jim Lyman Brian Williams Casey Child Mike Westfall the Year. 1970 1978 1986 Travis Flint 2003 Gary Cleverly Brian Graham Chris Schultis 1997 Matt Ciaramella Richard Hardy Jim Maynard 1987 Casey Child Jared Pena 1971 1979 Lance Madsen Nate Forbush Brady Martinez Steve Jones Marc Amicone 1988 Scott Pratt 2004 Steve Marlow Randy Gomez Lance Madsen 1998 Jay Brossman 1972 1980 1989 Nate Forbush Eric Chevalier Val Cahoon Randy Gomez Lance Madsen John Summers Matt Ciaramella The following is a look at Utah’s record, conference record, conference Year Record Conf. -

2019 Media Guide

WINNIPEG GOLDEYES 2019 MEDIA GUIDE WINNIPEG GOLDEYES 2019 SCHEDULE MAY JULY SEPTEMBER SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1234 10:00AM 1 4:00PM 2 7:00PM 3 7:00PM 4 7:00PM 5 7:00PM 6 6:00PM 1 1:00PM 2 1:00PM OPEN HOUSE FAR FAR FAR STP STP STP SF SF 5678 6:00PM 9 6:00PM 10 6:00PM 11 2:00PM 7 1:00PM 8 7:00PM 9 7:05PM 10 7:05PM 11 7:05PM 12 7:05PM 13 7:05PM FAR FAR FAR FAR STP STP LIN LIN LIN STP STP 2019 AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OPPONENTS 12 6:05PM 13 7:05PM 14 7:05PM 15 16 7:05PM 17 7:05PM 18 7:05PM 14 5:05PM 15 16 7:00PM 17 7:00PM 18 6:00PM 19 7:05PM 20 7:05PM CHI - CHICAGO DOGS (North Division) FOD CLE - CLEBURNE RAILROADERS (South Division) LIN KC KC TEX TEX TEX STP SF SF SF KC KC GOLF FAR - FARGO-MOORHEAD REDHAWKS (North Division) 19 2:05PM 20 7:06PM 21 7:06PM 22 1:05PM 23 24 7:00PM 25 6:00PM 21 1:05PM 22 23 24 7:00PM 25 7:00PM 26 7:00PM 27 6:00PM GAR - GARY SOUTHSHORE RAILCATS (North Division) KC - KANSAS CITY T-BONES (South Division) TEX CLE CLE CLE KC KC KC ALL-STAR TEX TEX TEX FAR STP LIN - LINCOLN SALTDOGS (South Division) 26 1:00PM 27 28 7:00PM 29 7:00PM 30 11:00AM 31 7:05PM 28 1:00PM 29 30 7:10PM 31 12:10PM MIL - MILWAUKEE MILKMEN (North Division) SC - SIOUX CITY EXPLORERS (South Division) KC GAR GAR GAR SF FAR GAR GAR SF - SIOUX FALLS CANARIES (South Division) STP - ST. -

Home Run Baseballs and Taxation, an Open Stance: How a H.R

HOME RUN BASEBALLS AND TAXATION, AN OPEN STANCE: HOW A H.R. CAN BE I.R.D. by Kelly A. Moore*and Adam J. Poe* I. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 79 II. HOME RUN BASEBALLS AS GROSS INCOME ...................... 81 III. RECENT HISTORY OF HOME RUN BASEBALL TAXATION.................85 IV. PROPOSAL-NONRECOGNITION AND IRD ................... 88 V. TRANSFER TAX CONSIDERATIONS ........... ................... 92 VI. CONCLUSION .......................................... ...... 95 I. INTRODUCTION A home run hitter steps to the plate. The pitcher peers into the catcher, who signals for a fastball. The pitcher gets set, winds up, and releases the baseball. Crack! As the baseball sails toward the right field bleachers, a fan sees it coming towards him. Dropping his beer, fighting the crowd, and risking injury, the fan catches the home run baseball. Returning to his seat, the fan imagines how great the baseball will look on his mantle and how this souvenir will become a family heirloom. Unbeknownst to the fan, the baseball may be cognizable as gross income under the Internal Revenue Code (Code)-he may have to pay an uncertain and possibly substantial amount of income tax, even though he has not received any extra cash or other liquid asset with which to do so. And to think, he dropped his $8 beer for this. In 2007, Matt Murphy faced such an uncertainty when he caught Barry Bonds' 756th career home run. With that home run, Bonds eclipsed Hank Aaron as Major League Baseball's all-time home run leader. Despite his stated desire to keep the baseball as a family heirloom, Murphy auctioned off the baseball for $752,467 to generate liquidity to pay the anticipated income tax liability.' Including the value of home run baseballs in gross income has been the subject of fierce debate.2 Murphy's experience is only among the most * Assistant Professor, University of Toledo College of Law. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 4/21/2020 Boston Bruins Edmonton Oilers 1183213 Bruce Cassidy believes Bruins’ ‘structure’ will be a benefit 1183243 Ryan Mantha's potential Oilers career never had a chance when (if) play resumes 1183244 Discount forward options the Oilers could pursue in free 1183214 The 2011 Bruins are reuniting Tuesday to watch their agency Stanley Cup clincher 1183245 ‘He was one in a million’: Colby Cave’s wife, Emily, opens 1183215 Bruins coach Bruce Cassidy making the most of his down up about her loss time 1183246 ‘Oh my God, Edmonton’s picking first’: An oral history of 1183216 Bruins Breakdown: Jaroslav Halak has been a great the 2015 NHL draft lottery addition 1183217 Bruce Cassidy says pause in NHL season hasn't changed Los Angeles Kings Bruins' goal 1183247 WEBSTER’S LEGACY LEAVES LASTING IMPACT: “HE 1183218 This week in Bruins playoff history: Lake Placid trip LOVED THE GAME, BUT HE LOVED PEOPLE” sparked Stanley Cup run in 2011 1183219 This Date in Bruins History: Boston beats rivals in high- Montreal Canadiens scoring games 1183248 Jeff Petry and P.K. Subban feed hospital workers, save 1183220 Entire 2011 Bruins team to reunite for Stanley Cup Game some jobs along the way 7 watch party 1183221 If hockey is to return this year, captains’ practices may Nashville Predators prove essential 1183249 Will the Predators try to re-sign Mikael Granlund and Craig 1183222 My favorite player: Rob Zamuner Smith? Can they? 1183223 Shinzawa: How I’d improve the NHL if I were commissioner New Jersey Devils 1183250 Position-by-position: NJ Devils have depth on wings but Buffalo Sabres few impact players 1183224 Sabres' No. -

2018 Event Information

2018 Event Information Event Partners www.BaseballCoachesClinic.com www.BaseballCoachesClinic.com January 2018 Dear Coach, Welcome to the 15th annual Mohegan Sun World Baseball Coaches’ Convention! We are excited to have you here. Our mission is to provide you with the very best in coaching education; and once again this year, we have secured the best clinicians and designed a curriculum that addresses all levels of play and a range of coaching areas. Here are a couple of clinic notes for 2018: - Again this year, we will offer you post-event access to video of our Thursday and Friday clinic sessions (close to 30 sessions!), so that you can refresh your memory or watch sessions you may have missed. See the postcard in your registration gift bag for the special promo code, which will enable you to purchase all sessions at a greatly discounted rate. We are confident you'll find these videos highly valuable. - To most conveniently provide you with the latest event information, we offer an event app that features the clinic schedule, a list of exhibitors, a digital version of the event handout and much more. Search Baseball Coaches Convention in the app stores. If you'd like to receive real-time event updates and news, please allow us to push event notifications to your device of choice. - We will offer a Talking Baseball Panel Discussion on Friday evening from 5:45PM - 7PM in Break-Out 1. Our panelists will discuss the game today and share past experiences, provide insights into what and who motivated them, and finish by taking questions from the audience. -

High-Scoring Baseball

High-Scoring Baseball Todd Guilliams Human Kinetics Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guilliams, Todd, 1966- High-scoring baseball / Todd Guilliams. p. cm. 1. Baseball--Scorekeeping. I. Title. GV879.G88 2012 796.357--dc23 2012020608 ISBN-10: 1-4504-1619-5 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-4504-1619-1 (print) Copyright © 2013 by Todd Guilliams All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information storage and retrieval system, is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. The web addresses cited in this text were current as of October 2012, unless otherwise noted. Notice: Permission to reproduce the following material is granted to instructors and agencies who have purchased High-Scoring Baseball: pp. 192, 193, 195, 197, 198, 202, 206, 210, 216, and 218. The reproduction of other parts of this book is expressly forbidden by the above copyright notice. Persons or agencies who have not purchased High-Scoring Baseball may not reproduce any material. Acquisitions Editor: Justin Klug; Developmental Editor: Anne Hall; Assistant Editor: Tyler Wolpert; Copyeditor: Bob Replinger; Permissions Manager: Martha Gullo; Graphic Designer: Joe Buck; Graphic Artist: Tara Welsch; Cover Designer: Keith Blomberg; Photograph (cover): Robert Williett/Raleigh News & Observer/MCT via Getty Images; Photographs (interior): Neil Bernstein, © Human Kinetics, unless otherwise noted; photos on pages 3, 15, 27, 43, 53, 83, 103, 125, 145, 161, 175, 199, and 213 courtesy of B. Kevin Smith, www.PhotoCR.com; Photo Asset Manager: Laura Fitch; Visual Production Assistant: Joyce Brumfield; Photo Production Manager: Jason Allen; Art Manager: Kelly Hendren; Associate Art Manager: Alan L. -

Student Activism and American Democracy in Cold War Los Angeles. Kurt Edward Kemper Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Reformers in the Marketplace of Ideas: Student Activism and American Democracy in Cold War Los Angeles. Kurt Edward Kemper Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kemper, Kurt Edward, "Reformers in the Marketplace of Ideas: Student Activism and American Democracy in Cold War Los Angeles." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7273. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7273 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Browns to Baltimore: Franchise Free Agency and the New Economics of the NFL Sanjay Jose' Mullick

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 7 Article 2 Issue 1 Fall Browns to Baltimore: Franchise Free Agency and the New Economics of the NFL Sanjay Jose' Mullick Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Sanjay Jose' Mullick, Browns to Baltimore: Franchise Free Agency and the New Economics of the NFL, 7 Marq. Sports L. J. 1 (1996) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol7/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BROWNS TO BALTIMORE: FRANCHISE FREE AGENCY AND THE NEW ECONOMICS OF THE NFL SANJAY JOSE' MULLICK* I. LEAGUE THINK "We're a group of 28 fat-cat Republicans who vote socialist on football." - Art Modell Owner, Cleveland Browns (former)1 In 1961, when the National Football League (hereinafter "NFL") convened for its owners meeting, it was prepared to endorse a new way of thinking that would change the face of the League, chart the course for the League's future and set an example for all professional sports.2 The NFL's new Commissioner, Pete Rozelle, convinced its founding families, including the Rooneys, Maras and Halases, to cede control of the television broadcast of their teams' games to the League itself. No longer would each team owner negotiate his own separate television contract; rather, the NFL would sell each team's television rights to the networks as a single package. -

7 Principles to Coaching Youth Hitting ® Hitting Philosophy

7 Principles to Coaching Youth Hitting ® Hitting Philosophy Principle 1: Be on Time & Be on Plane ………………………………………. 2 Principle 2: Mindset over Mechanics………………………………………….. 3 Principle 3: Have Rhythm & Timing…………………………………………….. 4 Principle 4: Hunt the Fastball………………………………………………………. 5 Principle 5: Hit with a Game Plan………………………………………………… 6 Principle 6: Mentally & Physically Tough……………………………………. 7 Principle 7: QAB’s over Statistics…………………………………………………. 8 Principle 1: Be on Time & Be on Plane! • Too often we focus on developing the “prettiest” swing. • Doesn’t matter what your swing looks like, if you’re not on time you don’t get to use it!! • Timing should be worked on in the hole & on deck… Not In the Box! • The barrel of the bat needs to be on plane with the pitch as long as possible! Coco Crisp Barrel on Plane Josh Donaldson Barrel on Plane Being on plane gives you more room for error. Timing needs to be done on deck! Principle 2: Mindset Over Mechanics! • Be less concerned with mechanics in the batter’s box and more concerned with competing! • We have to believe in ourselves as hitters! • Stop thinking about what your swing looks like and get in the box and focus on being the toughest hitter on the field! • Be FEARLESS! Principle 3: Have Rhythm & Timing! • To be a successful hitter, you must have consistent rhythm in your swing. • Don’t “Get your foot down early!” • Rhythm and timing are more important than the swing itself, and hitters should have a “Yes, Yes, No” mentality in the batter’s box. • The swing should be smooth and relaxed. -

15 2006 Results Batting Statistics Pitching

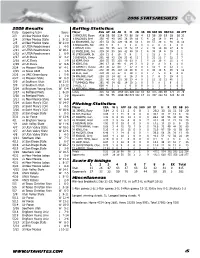

2006 STATS/RESULTS 2006 Results Batting Statistics Date Opposing team Score Player AVG GP GS AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI BB HBP SO SB ATT 2/3 at New Mexico State L 1-4 2 KHOURY, Ryan .438 56 56 224 73 98 18 4 13 56 39 19 28 16 21 2/4 at New Mexico State L 5-12 8 BALDWIN, Bret .358 45 40 165 36 59 16 5 4 28 14 0 44 2 4 2/5 at New Mexico State W 21-9 18 BROSSMAN, Jay .354 56 56 229 46 81 18 1 10 57 30 3 40 11 13 6 NAKAGAMA, Nic .333 3 0 3 1 1 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 2/10 at UTSA Roadrunners L 4-5 1 WELSH, John .326 55 55 221 44 72 17 2 8 41 10 10 37 6 9 2/11 at UTSA Roadrunners W 10-1 22 MOZELESKI, Joe .319 50 50 188 42 60 10 1 4 34 18 4 19 1 1 2/12 at UTSA Roadrunners L 6-9 40 STRINGHAM, Br. .310 15 6 29 5 9 1 1 2 12 3 0 7 0 0 2/17 at UC Davis W 3-2 3 SHIMADA, Corey .301 49 43 136 31 41 11 1 5 31 22 7 32 3 7 2/18 at UC Davis L 1-9 16 KEMP, Erich .300 55 55 210 40 63 9 1 4 23 30 4 31 3 4 2/19 at UC Davis W 9-6 34 KING, Eric .286 17 11 49 6 14 3 0 2 8 8 0 6 0 0 2/24 vs Missouri State W 4-1 33 GARRETT, Clayne .283 30 12 60 7 17 3 0 1 12 4 0 12 1 1 2/25 vs Texas A&M L 1-6 29 KMETKO, Tyler .272 45 36 147 23 40 6 0 4 30 13 6 35 9 12 24 BELL, Josh .270 20 13 37 8 10 1 0 1 7 5 0 6 0 0 2/26 vs UNC Greensboro L 5-6 39 MALONE, Scott .258 28 14 62 4 16 3 0 1 7 6 3 19 0 1 2/27 vs Missouri State W 6-3 10 FRANK, Adam .221 46 40 131 30 29 4 0 2 21 13 12 46 1 2 3/9 at Southern Utah W 11-5 7 TUMMOLO, Mike .161 40 14 62 14 10 2 0 1 5 8 1 8 0 1 3/9 at Southern Utah L 10-12 9 WISE, T.J. -

2014 Lansing Lugnuts Media Guide

2014 Media Guide Table of Contents 2014 Lugnuts Media Guide Great Lakes Loons ................................................31 Lake County Captains ...........................................32 Staff Directory ..........................................................3 South Bend Silver Hawks ......................................33 Co-Owners Tom Dickson and Sherrie Myers ..........4 West Michigan Whitecaps .....................................34 Front Office General Manager Nick Grueser...............................4 Beloit Snappers .....................................................35 Assistant General Manager Nick Brzezinski............4 Burlington Bees .....................................................35 Promotional Schedule .............................................5 Cedar Rapids Kernels ...........................................36 Clinton LumberKings .............................................36 Kane County Cougars ...........................................37 2014 Lugnuts Peoria Chiefs .........................................................37 Quad Cities River Bandits .....................................38 Manager John Tamargo, Jr. .....................................7 Wisconsin Timber Rattlers .....................................38 Hitting Coach Ken Huckaby.....................................7 2014 Lugnuts Pitching Coach Vince Horsman ...............................7 Athletic Trainer Drew MacDonald ............................7 History Justin Atkinson.........................................................8