Could Cleveland Have Kept the Browns by Exercising Its Eminent Domain Power? Steven R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Modell (1925-2012)

ART MODELL (1925-2012) Art Modell, whose remarkable 43-year NFL career made him a regular finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, died today of natural causes at Johns Hopkins Hospital at the age of 87. Former Ravens president David Modell issued this statement: “Sadly, I can confirm that my father died peacefully of natural causes at four this morning. My brother John Modell and I were with him when he finally rejoined the absolute love of his life, my mother Pat Modell, who passed away last October. “’Poppy’ was a special man who was loved by his sons, his daughter-in-law Michel, and his six grandchildren. Moreover, he was adored by the entire Baltimore community for his kindness and generosity. And, he loved Baltimore. He made an important and indelible contribution to the lives of his children, grandchildren and his entire community. We will miss him.” As owner of both the Cleveland Browns (1961-1995) and the Baltimore Ravens (1996-2003), Modell directed teams that produced 28 winning seasons, 28 playoff games, two NFL Championships (1964 and 2000), three other appearances in NFL title contests (1965, ’68 and ’69), and four visits (1986, ’87, ’89 and 2000) to AFC Championships. A key figure in launching Monday Night Football, Modell chaired the NFL’s Television Committee for 31 years, setting the standard for rights’ fees for professional sports and TV networks. He was the only elected NFL president (1967-69) and he was Chairman of the Owners’ Labor Committee, which negotiated the NFL’s first collective bargaining unit with the players. -

2019 Media Guide

2019 MEDIA GUIDE WWW.UTAHUTES.COM | @UTAHBASEBALL 1 2019 MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS TEAM INFORMATION Table of Contents 2 On May 23, 2018, the NCAA Committee on Infractions released its statement on the two Level Quick Facts 3 II violations sanctioned against the University of Utah baseball program. The violations are Covering the Utes/Media Information 4 related to impermissible practice and coaching activities by a non-coaching staff member. 2019 Schedule 5 2019 Roster/Pronunciation Guide 6-7 Starting in 2014-15, a sport-specific staff member, who was not designated as one of the four permissible coaches, engaged in impermissible on-field instruction. Specifically, the 2019 UTAH BASEBALL OUTLOOK staff member provided instruction to catchers, threw batting practice, and occasionally hit 2018 Season Outlook 9-10 baseballs to pitchers for fielding practice. This continued through the 2016-17 academic year. 2018 Opponents 11-13 As a result, the Utah baseball program exceeded the number of permissible coaches. UTAH BASEBALL COACHING STAFF After initiating an internal investigation, Utah turned over information to the NCAA. The Head Coach Bill Kinneberg 15-17 institution and the NCAA collaborated to finalize the investigation. Utah self-imposed three Associate Head Coach Mike Crawfod 18 penalties, which include: a $5,000 financial penalty, a reduction in countable athletically Assistant Coach Jay Brossman 19 related activities for the 2018 baseball season, and a suspension of the head coach for the Director of Operations Sydney Jones 20 first 25% of the 2018 baseball season. Volunteer Assistant Parker Guinn 20 Utah Athletic Administration 20 In addition to the aforementioned penalties, the NCAA applied a one-year probationary period and imposed public reprimand and censure. -

Players on Art Modell

PLAYERS ON ART MODELL Former Broncos and Ravens TE Shannon Sharpe: “Mr. Modell was one of the main reasons I came to Baltimore. I remember when I met him. He flew down to see me, and we flew back up to Baltimore together, and he learned so much about me and my family, and I learned about him as a man. I remember his words so vividly: He said, ‘Ozzie, get this deal done,’ and that was the start of something beautiful. “One of my favorite moments in the NFL was when he spoke to us in the locker room after the Super Bowl victory. He said, ‘This is the proudest day of my life; you guys make me proud.’ And then he started to break down. That touched me. You could not only see the emotion from him and from all of us in that room, you could feel it. Knowing how long he had been in the NFL and how many great players he had been around, it was such a great feeling to give him something that he wanted for so long. We all wanted it for him! “You see how close he was with his boys and how much he loved his wife, and he brought that atmosphere to the Ravens. He always had something positive to say, always had a joke to make you smile. I still picture him on his golf cart watching every practice, no matter what the weather was like. We were all in it together. The sport you see on TV today and what the NFL means to our society is in large part due to Mr. -

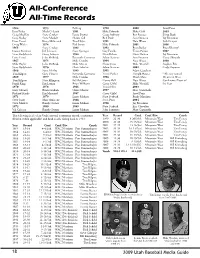

The University of Utah

All-Conference All-Time Records 1964 1973 Ed Iorg 1990 2000 Jared Pena Jerry Fisher Mark Colerick 1981 Mike Edwards Mike Goff 2005 Craig MacKay Steve Cowley Lance Brewer Craig Sudbury Brit Pannier Doug Beck Gary Shelby Steve Marlow Shawn Gill Rob Beck Sam Swenson Jay Brossman Dave Varvel Kerry Milkovich Tim Hayes 1991 Nate Weese Josh Cooper Doug Wasko 1974 Phil Strom Mike Edwards 2001 2006 1965 Steve Cowley 1982 1992 Ryan Bailey Ryan Khoury* Duane Freeman Jeff Johnson Steve Springer Guy Fowlks Travis Palmer 2007 Steve Radulovich Gerry LeFavor 1984 Clint Kelson Chris Shelton Jay Brossman Dave Varvel John McBride Fernando Carmona Adam Sessions Sam Swenson Corey Shimada 1967 1975 Mike Dandos 1994 Nate Weese 2008 Mike Beyler John McBride Mike Moore Shane Jones Mike Westfall Stephen Fife Steve Radulovich 1976 Chris Schultis Adam Sessions 2002 Cody Guymon 1968 Scott Moffitt 1985 1995 Adam Castelton Tom Kilgore Gary Vincent Fernando Carmona Travis Parker Donald Hawes * Khoury named 1969 1977 Mike Dandos 1996 Mitch Maio Mountain West Tom Kilgore Nate Ellington Ed McCarter Danny Bell Nate Weese Conference Player of Frank King Jim Lyman Brian Williams Casey Child Mike Westfall the Year. 1970 1978 1986 Travis Flint 2003 Gary Cleverly Brian Graham Chris Schultis 1997 Matt Ciaramella Richard Hardy Jim Maynard 1987 Casey Child Jared Pena 1971 1979 Lance Madsen Nate Forbush Brady Martinez Steve Jones Marc Amicone 1988 Scott Pratt 2004 Steve Marlow Randy Gomez Lance Madsen 1998 Jay Brossman 1972 1980 1989 Nate Forbush Eric Chevalier Val Cahoon Randy Gomez Lance Madsen John Summers Matt Ciaramella The following is a look at Utah’s record, conference record, conference Year Record Conf. -

Why Venue Owners Need to Consider the Importance of Flexibility in Sponsorship Agreements

March-April 2018 l Volume 2, Issue 6 Route To: ____/____/____/____ How the law affects the sports facilities industry and the The Lasting Legacy of Art Modell Felt As Columbus Crew Seeks To Set Sail for Austin By Scott Andresen, of Andresen & rience, the Ohio state legislature enacted Associates, P.C. Ohio Revised Code §9.6 a year later on THIS ISSUE June 20, 1996. Officially titled Restrictions The Lasting Legacy of Art he Move. on owner of professional sports team that Modell Felt As Columbus T While that phrase may have very uses a tax-supported facility, the law is Crew Seeks To Set Sail little import throughout the sporting world less-than-affectionately known as the “Art for Austin 1 generally, it has had a lasting impact in state Modell Law.” The law states as follows: NCAA Fallout from NC of Ohio that is still being felt 23 years later. No owner of a professional sports team Bathroom Bill Taints College The Move refers to the decision by team that uses a tax-supported facility for most Sports Landscape 1 owner Art Modell to move his Cleveland of its home games and receives financial Browns team to Baltimore during the 1995 assistance from the state or a political sub- Re-examining Steep Spectator Seating 2 NFL season. Subsequent litigation seeking division thereof shall cease playing most to prevent The Move (see City of Cleveland of its home games at the facility and begin Winning the Gold: Why v. Cleveland Browns, et al., Cuyahoga playing most of its home games elsewhere Venue Owners Need to County Court of Common Pleas Case No. -

2019 Media Guide

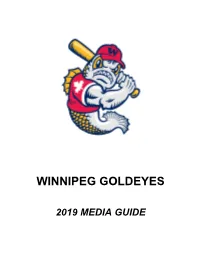

WINNIPEG GOLDEYES 2019 MEDIA GUIDE WINNIPEG GOLDEYES 2019 SCHEDULE MAY JULY SEPTEMBER SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1234 10:00AM 1 4:00PM 2 7:00PM 3 7:00PM 4 7:00PM 5 7:00PM 6 6:00PM 1 1:00PM 2 1:00PM OPEN HOUSE FAR FAR FAR STP STP STP SF SF 5678 6:00PM 9 6:00PM 10 6:00PM 11 2:00PM 7 1:00PM 8 7:00PM 9 7:05PM 10 7:05PM 11 7:05PM 12 7:05PM 13 7:05PM FAR FAR FAR FAR STP STP LIN LIN LIN STP STP 2019 AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OPPONENTS 12 6:05PM 13 7:05PM 14 7:05PM 15 16 7:05PM 17 7:05PM 18 7:05PM 14 5:05PM 15 16 7:00PM 17 7:00PM 18 6:00PM 19 7:05PM 20 7:05PM CHI - CHICAGO DOGS (North Division) FOD CLE - CLEBURNE RAILROADERS (South Division) LIN KC KC TEX TEX TEX STP SF SF SF KC KC GOLF FAR - FARGO-MOORHEAD REDHAWKS (North Division) 19 2:05PM 20 7:06PM 21 7:06PM 22 1:05PM 23 24 7:00PM 25 6:00PM 21 1:05PM 22 23 24 7:00PM 25 7:00PM 26 7:00PM 27 6:00PM GAR - GARY SOUTHSHORE RAILCATS (North Division) KC - KANSAS CITY T-BONES (South Division) TEX CLE CLE CLE KC KC KC ALL-STAR TEX TEX TEX FAR STP LIN - LINCOLN SALTDOGS (South Division) 26 1:00PM 27 28 7:00PM 29 7:00PM 30 11:00AM 31 7:05PM 28 1:00PM 29 30 7:10PM 31 12:10PM MIL - MILWAUKEE MILKMEN (North Division) SC - SIOUX CITY EXPLORERS (South Division) KC GAR GAR GAR SF FAR GAR GAR SF - SIOUX FALLS CANARIES (South Division) STP - ST. -

Home Run Baseballs and Taxation, an Open Stance: How a H.R

HOME RUN BASEBALLS AND TAXATION, AN OPEN STANCE: HOW A H.R. CAN BE I.R.D. by Kelly A. Moore*and Adam J. Poe* I. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 79 II. HOME RUN BASEBALLS AS GROSS INCOME ...................... 81 III. RECENT HISTORY OF HOME RUN BASEBALL TAXATION.................85 IV. PROPOSAL-NONRECOGNITION AND IRD ................... 88 V. TRANSFER TAX CONSIDERATIONS ........... ................... 92 VI. CONCLUSION .......................................... ...... 95 I. INTRODUCTION A home run hitter steps to the plate. The pitcher peers into the catcher, who signals for a fastball. The pitcher gets set, winds up, and releases the baseball. Crack! As the baseball sails toward the right field bleachers, a fan sees it coming towards him. Dropping his beer, fighting the crowd, and risking injury, the fan catches the home run baseball. Returning to his seat, the fan imagines how great the baseball will look on his mantle and how this souvenir will become a family heirloom. Unbeknownst to the fan, the baseball may be cognizable as gross income under the Internal Revenue Code (Code)-he may have to pay an uncertain and possibly substantial amount of income tax, even though he has not received any extra cash or other liquid asset with which to do so. And to think, he dropped his $8 beer for this. In 2007, Matt Murphy faced such an uncertainty when he caught Barry Bonds' 756th career home run. With that home run, Bonds eclipsed Hank Aaron as Major League Baseball's all-time home run leader. Despite his stated desire to keep the baseball as a family heirloom, Murphy auctioned off the baseball for $752,467 to generate liquidity to pay the anticipated income tax liability.' Including the value of home run baseballs in gross income has been the subject of fierce debate.2 Murphy's experience is only among the most * Assistant Professor, University of Toledo College of Law. -

The Relocation of the Cleveland Browns

The Cultural Nexus of Sport and Business: The Relocation of the Cleveland Browns Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew David Linden, B.A. Graduate Program in Education and Human Ecology The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Melvin L. Adelman, Advisor Dr. Sarah K. Fields Copyright by Andrew David Linden 2012 Abstract On November 6, 1995, Arthur Modell announced his intention to transfer the Cleveland Browns to Baltimore after the conclusion of the season. Throughout the ensuing four months, the cities of Cleveland and Baltimore, along with Modell, National Football League (NFL) officials and politicians, battled over the future of the franchise. After legal and social conflicts, the NFL and Cleveland civic officials agreed on a deal that allowed Modell to honor his contract with Baltimore and simultaneously provided an NFL team to Cleveland to begin play in 1999. This settlement was unique because it allowed Cleveland to retain the naming rights, colors, logo, and, most significantly, the history of the Browns. This thesis illuminates the cultural nexus between sport and business. A three chapter analysis of the cultural meanings and interpretations of the Browns‘ relocation, it examines the ways in which the United States public viewed the economics of professional team sport in the United States near the turn of the twenty-first century and the complex relationship between the press, sports entrepreneurs and community. First, Cleveland Browns‘ fan letters from the weeks following Modell‘s announcement along with newspaper accounts of the ―Save Our Browns‖ campaign convey that the reaction of Cleveland‘s populace to Modell‘s announcement was tied to their antipathy toward the city‘s negative national notoriety and underscored their feelings toward the city‘s urban ii decline in the late 1990s. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 4/21/2020 Boston Bruins Edmonton Oilers 1183213 Bruce Cassidy believes Bruins’ ‘structure’ will be a benefit 1183243 Ryan Mantha's potential Oilers career never had a chance when (if) play resumes 1183244 Discount forward options the Oilers could pursue in free 1183214 The 2011 Bruins are reuniting Tuesday to watch their agency Stanley Cup clincher 1183245 ‘He was one in a million’: Colby Cave’s wife, Emily, opens 1183215 Bruins coach Bruce Cassidy making the most of his down up about her loss time 1183246 ‘Oh my God, Edmonton’s picking first’: An oral history of 1183216 Bruins Breakdown: Jaroslav Halak has been a great the 2015 NHL draft lottery addition 1183217 Bruce Cassidy says pause in NHL season hasn't changed Los Angeles Kings Bruins' goal 1183247 WEBSTER’S LEGACY LEAVES LASTING IMPACT: “HE 1183218 This week in Bruins playoff history: Lake Placid trip LOVED THE GAME, BUT HE LOVED PEOPLE” sparked Stanley Cup run in 2011 1183219 This Date in Bruins History: Boston beats rivals in high- Montreal Canadiens scoring games 1183248 Jeff Petry and P.K. Subban feed hospital workers, save 1183220 Entire 2011 Bruins team to reunite for Stanley Cup Game some jobs along the way 7 watch party 1183221 If hockey is to return this year, captains’ practices may Nashville Predators prove essential 1183249 Will the Predators try to re-sign Mikael Granlund and Craig 1183222 My favorite player: Rob Zamuner Smith? Can they? 1183223 Shinzawa: How I’d improve the NHL if I were commissioner New Jersey Devils 1183250 Position-by-position: NJ Devils have depth on wings but Buffalo Sabres few impact players 1183224 Sabres' No. -

15 Modern-Era Finalists for Hall of Fame Election Announced

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 11, 2013 Joe Horrigan at (330) 588-3627 15 MODERN-ERA FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION ANNOUNCED Four first-year eligible nominees – Larry Allen, Jonathan Ogden, Warren Sapp, and Michael Strahan – are among the 15 modern-era finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Selection Committee meets in New Orleans, La. on Saturday, Feb. 2, 2013. Joining the first-year eligible, are eight other modern-era players, a coach and two contributors. The 15 modern-era finalists, along with the two senior nominees announced in August 2012 (former Kansas City Chiefs and Houston Oilers defensive tackle Curley Culp and former Green Bay Packers and Washington Redskins linebacker Dave Robinson) will be the only candidates considered for Hall of Fame election when the 46-member Selection Committee meets. The 15 modern-era finalists were determined by a vote of the Hall’s Selection Committee from a list of 127 nominees that earlier was reduced to a list of 27 semifinalists, during the multi-step, year-long selection process. Culp and Robinson were selected as senior candidates by the Hall of Fame’s Seniors Committee. The Seniors Committee reviews the qualifications of those players whose careers took place more than 25 years ago. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. The Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee’s 17 finalists (15 modern-era and two senior nominees*) with their positions, teams, and years active follow: • Larry Allen – Guard/Tackle – 1994-2005 Dallas Cowboys; 2006-07 San Francisco 49ers • Jerome Bettis – Running Back – 1993-95 Los Angeles/St. -

2018 Event Information

2018 Event Information Event Partners www.BaseballCoachesClinic.com www.BaseballCoachesClinic.com January 2018 Dear Coach, Welcome to the 15th annual Mohegan Sun World Baseball Coaches’ Convention! We are excited to have you here. Our mission is to provide you with the very best in coaching education; and once again this year, we have secured the best clinicians and designed a curriculum that addresses all levels of play and a range of coaching areas. Here are a couple of clinic notes for 2018: - Again this year, we will offer you post-event access to video of our Thursday and Friday clinic sessions (close to 30 sessions!), so that you can refresh your memory or watch sessions you may have missed. See the postcard in your registration gift bag for the special promo code, which will enable you to purchase all sessions at a greatly discounted rate. We are confident you'll find these videos highly valuable. - To most conveniently provide you with the latest event information, we offer an event app that features the clinic schedule, a list of exhibitors, a digital version of the event handout and much more. Search Baseball Coaches Convention in the app stores. If you'd like to receive real-time event updates and news, please allow us to push event notifications to your device of choice. - We will offer a Talking Baseball Panel Discussion on Friday evening from 5:45PM - 7PM in Break-Out 1. Our panelists will discuss the game today and share past experiences, provide insights into what and who motivated them, and finish by taking questions from the audience. -

High-Scoring Baseball

High-Scoring Baseball Todd Guilliams Human Kinetics Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guilliams, Todd, 1966- High-scoring baseball / Todd Guilliams. p. cm. 1. Baseball--Scorekeeping. I. Title. GV879.G88 2012 796.357--dc23 2012020608 ISBN-10: 1-4504-1619-5 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-4504-1619-1 (print) Copyright © 2013 by Todd Guilliams All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information storage and retrieval system, is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. The web addresses cited in this text were current as of October 2012, unless otherwise noted. Notice: Permission to reproduce the following material is granted to instructors and agencies who have purchased High-Scoring Baseball: pp. 192, 193, 195, 197, 198, 202, 206, 210, 216, and 218. The reproduction of other parts of this book is expressly forbidden by the above copyright notice. Persons or agencies who have not purchased High-Scoring Baseball may not reproduce any material. Acquisitions Editor: Justin Klug; Developmental Editor: Anne Hall; Assistant Editor: Tyler Wolpert; Copyeditor: Bob Replinger; Permissions Manager: Martha Gullo; Graphic Designer: Joe Buck; Graphic Artist: Tara Welsch; Cover Designer: Keith Blomberg; Photograph (cover): Robert Williett/Raleigh News & Observer/MCT via Getty Images; Photographs (interior): Neil Bernstein, © Human Kinetics, unless otherwise noted; photos on pages 3, 15, 27, 43, 53, 83, 103, 125, 145, 161, 175, 199, and 213 courtesy of B. Kevin Smith, www.PhotoCR.com; Photo Asset Manager: Laura Fitch; Visual Production Assistant: Joyce Brumfield; Photo Production Manager: Jason Allen; Art Manager: Kelly Hendren; Associate Art Manager: Alan L.