Itzhak Perlman Violinist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

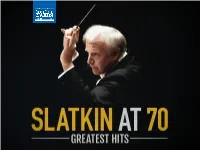

Leonard Slatkin at 70: the DSO's Music Director Was Born for The

Leonard Slatkin at 70: The DSO’s music director was born for the podium By Lawrence B. Johnson Some bright young musicians know early on that they want to be a conductor. Leonard Slatkin, who turned 70 Slatkin at 70: on September 1, had a more specific vision. He believed himself born to be a music director. Greatest Hits “First off, it was pretty clear that I would go into conducting once I had the opportunity to actually lead an orchestra,” says Slatkin, music director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra since 2008 and occupant of the same post with the Orchestre National de Lyon since 2011. “The study process suited my own ethic and, at least for me, I felt relatively comfortable with the technical part of the job.” “But perhaps more important, I knew that I would also be a music director. Mind you, this is a very different job from just getting on the podium and waving your arms. The decision making process and the ability to shape a single ensemble into a cohesive whole, including administration, somehow felt natural to me.” Slatkin arrived at the DSO with two directorships already under his belt – the Saint Louis Symphony (1979-96) and the National Symphony in Washington, D.C. (1996-2008) – and an earful of caution about the economically distressed city and the hard-pressed orchestra to which he was being lured. But it was a challenge that excited him. “Almost everyone warned me about the impending demise of the orchestra,” the conductor says. “A lot of people said that I should not take it. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

Leonard Bernstein

TuneUp! TuneUSaturday, October 18th, 2008 p! New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concert® elcome to a new season of Young People’s Concerts! Throughout history, there have been special times when music flowered in specific cities—Capitals of Music—that for a while W became the center of the musical world. Much of the music we know today comes from these times and places. But how did these great flowerings of music happen? That’s what we’ll find out this year as we discover the distinctive sounds of four of these Capitals. And where better to start than right here in New York? After the Second World War, our city became a cultural capital of the world. Leonard Bernstein—who became Music Director of the New York Philharmonic 50 years ago this fall—defined music in New York in his roles as composer, conductor, and teacher. So what was it like in New York back then? Let’s find out from a child of that time—Leonard Bernstein’s BERNSTEIN’S NEW YORK daughter Jamie! THE PROGRAM: BERNSTEIN “The Great Lover” from On the Town COPLAND “Skyline” from Music for a Great City (excerpt) GERSHWIN “I Got Rhythm” from Girl Crazy BERNSTEIN “America” from West Side Story Suite No. 2 COPLAND Fanfare for the Common Man Jamie Bernstein, host BERNSTEIN On the Waterfront Symphonic Suite (excerpt) Delta David Gier, conductor SEBASTIAN CURRIER “quickchange” from Microsymph Tom Dulack, scriptwriter and director BERNSTEIN Overture to Candide 1 2 3 5 4 CAN YOU IDENTIFY EVERYTHING IN AND AROUND LEONARD BERNSTEIN’S NEW YORK STUDIO? LOOK ON THE BACK PAGE TO SEE WHETHER YOU’RE RIGHT. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Our History 1971-2018 20 100 Contents

OUR HISTORY 1971-2018 20 100 CONTENTS 1 From the Founder 4 A Poem by Aaron Stern 6 Our Mission 6 Academy Timeline 8 Academy Programs 22 20 Years in Pictures 26 20 Years in Numbers 26 Where We’ve Worked 27 20th Anniversary Events 28 20th Anniversary Images Send correspondence to: Laura Pancoast, Development Coordinator 133 Seton Village Road Santa Fe, NM 87508 [email protected] ON THE COVER & LEFT: Academy for the Love of Learning photo © Kate Russell 20 YEARS of the Academy for the Love of Learning Copyright © 2018 Academy for the Love of Learning, Inc. 2018 has been a very special year, as it marks the 20th anniversary of FROM THE FOUNDER the Academy’s official founding in 1998. 2018 is also, poignantly and coincidentally, the 100th anniversary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth. Lenny, as I knew him, the great musician, the 20th century giant with whom, in 1986, I conceived the Academy, was one of the first people with whom I engaged in dialogue about “this thing,” as he called it, just before proposing that we call our “thing” the Academy for the Love of Learning. “Why that name?”, I asked – and he said: “because you believe that if we truly open ourselves to learning, it will liberate us and bring us home, individually and collectively. So, the name is perfect, because the acronym is ALL!” I resisted it at first, but soon came to realize that the name indeed was perfect. This and other prescient dialogues have helped us get to where we are today – a thriving, innovative organization. -

20 Lc 39 2635 Hr 1444

20 LC 39 2635 House Resolution 1444 By: Representative Howard of the 124th A RESOLUTION 1 Honoring the life and memory of Ms. Jessye Norman and dedicating an interchange in her 2 memory; and for other purposes. 3 WHEREAS, Ms. Jessye Norman was born on September 15, 1945, in Augusta, Georgia, the 4 beloved daughter of Janie King Norman and Silas Norman; and 5 WHEREAS, after graduating from Lucy C. Laney High School, Ms. Norman earned a 6 bachelor's degree from Howard University and a master's degree from the University of 7 Michigan; and 8 WHEREAS, a renowned opera singer, Ms. Norman performed Deborah, L'Africaine, and Le 9 Nozze di Figaro for the Deutsche Oper Berlin opera company; and 10 WHEREAS, in 1982, she performed Oedipus Rex and Dido and Aeneas with the Opera 11 Company of Philadelphia; and 12 WHEREAS, other notable performances include the 100th anniversary season with the 13 Metropolitan Opera and appearances with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Lyric 14 Opera of Chicago; and 15 WHEREAS, in 2002, she established the Jessye Norman School of Arts, a tuition-free after 16 school arts program in Augusta; and 17 WHEREAS, her remarkable talents have been recognized with five Grammy Awards, 18 including a Lifetime Achievement Award; and 19 WHEREAS, it is abundantly fitting and proper that this remarkable and distinguished 20 Georgian be recognized appropriately by dedicating an interchange in her memory. H. R. 1444 - 1 - 20 LC 39 2635 21 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED AND ENACTED BY THE GENERAL 22 ASSEMBLY OF GEORGIA that the interchange between Interstate 20 and Washington 23 Road in Richmond County is dedicated as the Jessye Norman Memorial Interchange. -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

825646078936.Pdf

ITZHAK PERLMAN LIVE IN THE FIDDLER’S HOUSE plays familiar Jewish melodies arranged by Dov Seltzer 25 Bukovina 212 (Trad. arr. Alpert/Bern) 4.30 1 A Yiddishe Mamme 6.48 26 Lekho Neraneno (Trad. arr. Brave Old World) 5.00 2 As der Rebbe Elimelech is gevoyrn asoi freylach * 5.51 27 Doina Naftule (Trad. arr. Bjorling) 2.43 3 Reyzele * 4.10 28 A Hora mit Branfn (Trad. arr. Bjorling) 3.24 4 Oif’n Pripetchik brennt a feier’l 4.05 29 Healthy Baby Girl (Suigals) 2.16 5 Doyna * 3.39 30 Golem Tants (London) 1.49 6 Rozhinkes mit Mandelen 5.37 31 Honga Encore (Trad. arr. London) 1.35 7 Oif’n Weyg steyt a Boim 5.25 32 Nign (Sklamberg) 5.31 8 A Dudele * 4.50 33 Bulgars/The Kiss (Trad. arr. The Klezmatics/London) 5.07 9 Viahin soll ich geyn? 4.54 34 Meton Nign/In the Sukke 6.02 35 Sholom Aleykhem 4.33 36 Khaiterma 2.55 ITZHAK PERLMAN violin 37 Andy’s Ride 2.55 ISRAEL ZOHAR clarinet* 38 A Heymischer Bulgar/Wedding Dance (Trad. arr. Ellstein) 3.14 Israel Philharmonic Orchestra/Dov Seltzer 39 Kale Bazetsn (Seating the Bride)/Khusidl (Hasidic Dance) 4.30 (Trad. arr. Tarras) 40 Fun Tashlikh 3.01 IN THE FIDDLER’S HOUSE 41 A Yingele fun Poyln (A Young Man from Poland)/ 4.59 Di Mame iz Gegangen in Mark Arayn (Mother Went to Market) 10 Reb Itzik’s Nign * 6.01 42 Processional — (Trad. arr. Netzky and ‘Klezcorps’) 12.16 ‡ 11 Simkhes Toyre Time 3.22 Klezmer Suite — (Trad. -

Honoring Itzhak Perlman

The Trustees of the Westport Library are pleased to present the twenty-second for the evening™ Honoring Itzhak Perlman REMARKS Iain Bruce President, Board of Trustees Bill Harmer Executive Director, Westport Library TRIBUTES AND PERFORMANCES HONORING ITZHAK PERLMAN American String Quartet Peter Winograd, violin Daniel Avshalomov, viola Laurie Carney, violin Wolfram Koessel, cello Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) String Quartet in F Major (1903) IV. Finale: Vif et agité Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904) Piano Quintet No. 2 in A Major, Op. 81 (1887) I. Allegro, ma non tanto Rohan De Silva, pianist A TALK WITH ITZHAK PERLMAN With Andrew C. Wilk, Executive Producer WESTPORT LIBRARY AWARD Presented by Bill Harmer, Executive Director for the evening ™ A Benefit for the Westport Library HONORING ITZHAK PERLMAN Itzhak Perlman rose to fame on the Rohan De Silva Born in Sri Lanka, Rohan Ed Sullivan show, where he performed as a De Silva studied at the Royal Academy child prodigy at just 13 years old. Perlman of Music and at The Juilliard School. He has performed with every major orchestra has collaborated with many of the world’s and at venerable concert halls around the top violinists in recitals, including Pinchas globe. Perlman was granted a Presidential Zukerman, Joshua Bell, Gil Shaham Medal of Freedom by President Obama and Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg. in 2015, the nation’s highest civilian A highly sought after collaborative pianist honor, a Kennedy Center Honor in 2003, and chamber musician, De Silva has a National Medal of Arts by President collaborated for over twenty years with Itzhak Perlman as his Clinton in 2000 and a Medal of Liberty by President Reagan in 1986. -

Bergenpac.Org UPCOMING SHOWS on the TAUB STAGE at BERGENPAC

2019-2020 bergenpac.org UPCOMING SHOWS ON THE TAUB STAGE AT BERGENPAC DECEMBER (CONT.) 2019 The Very Hungry Caterpillar featuring Dream Snow & Other 15 1pm & 4pm OCTOBER Eric Carle Favorites presented by PSE&G 3 8:00pm Vince Neil of Mötley Crüe presented by WDHA 17 7:00pm Lior Suchard: The Israeli Illusionist – ON SALE SOON! 4 8:00pm Steven Wright presented by Johl & Company 20 8:00pm A Christmas Carol The Musical presented by bergenPAC 5 8:00pm Michael Martocci presents Sinatra Meets The Sopranos 21 1pm & 4:30pm A Christmas Carol The Musical presented by bergenPAC 6 1:00pm Jeff Boyer’s Big Bubble Bonanza 22 1:00pm A Christmas Carol The Musical presented by bergenPAC 10 8:00pm Rick Wakeman: Grumpy Old Man Tour 11 8:00pm Explosion de la Salsa de Ayer 2020 JANUARY 13 7:30pm Gin Blossoms: The New Miserable Experience Satisfaction: The International Rolling Stones Tribute Show: 15 7:30pm So You Think You Can Dance Live! 2019 4 8:00pm Paint It Black 16 8:00pm TOTO: 40 Trips Around the Sun; Benzel-Busch Concert Series New Jersey Symphony Orchestra presents Winter Festival: My Fellow Supporters of the Arts, 9 7:30pm 19 8:00pm The Jim Breuer Residency: Comedy, Stories & More Vol. III Mozart’s Don Giovanni Sergio Mendes & Bebel Gilberto: The 60th Anniversary 11 8:00pm The Capitol Steps: The Lyin’ Kings I am excited to share Bergen Performing Art Center’s 2019-20 lineup 20 7:30pm of Bossa Nova with you today. Boasting a variety of headliners, up-and-comers and 12 3:00pm Neil Berg’s 104 Years of Broadway Mystery Science Theater 3000 Live: The Great Cheesy everything in between across the genres, we expect everyone will find 24 8:00pm 17 8:00pm The Simon & Garfunkel Story: A Tribute to Simon & Garfunkel something they love.