Fisherman Without a Boat: Observations on the Contemporary Clans' System in Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Socio-Cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women's

A Socio-cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women’s Perception of and Responses to HIV and AIDS from the Two Selected Tribes in Rural Fiji Tabalesi na Dakua,Ukuwale na Salato Ms Litiana N. Tuilaselase Kuridrani MBA; PG Dip Social Policy Admin; PG Dip HRM; Post Basic Public Health; BA Management/Sociology (double major); FRNOB A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Population Health Abstract This thesis reports the findings of the first in-depth qualitative research on the socio-cultural perceptions of and responses to HIV and AIDS from the two selected tribes in rural Fiji. The study is guided by an ethnographic framework with grounded theory approach. Data was obtained using methods of Key Informants Interviews (KII), Focus Group Discussions (FGD), participant observations and documentary analysis of scripts, brochures, curriculum, magazines, newspapers articles obtained from a broad range of Fijian sources. The study findings confirmed that the Indigenous Fijian women population are aware of and concerned about HIV and AIDS. Specifically, control over their lives and decision-making is shaped by changes of vanua (land and its people), lotu (church), and matanitu (state or government) structures. This increases their vulnerabilities. Informants identified HIV and AIDS with a loss of control over the traditional way of life, over family ties, over oneself and loss of control over risks and vulnerability factors. The understanding of HIV and AIDS is situated in the cultural context as indigenous in its origin and required a traditional approach to management and healing. -

The Case for Lau and Namosi Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali

ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI MASILINA TUILOA ROTUIVAQALI ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce Copyright © 2012 by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali School of Accounting & Finance Faculty of Business & Economics The University of the South Pacific September, 2012 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature………………………………. Date……………………………… Name: Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali Student ID No: S00001259 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mrs. Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali. Signature……………………………… Date………………………………... Name: Michael Millin White Designation: Professor in Accounting DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my beloved daughters Adi Filomena Rotuisolia, Adi Fulori Rotuisolia and Adi Losalini Rotuisolia and to my niece and nephew, Masilina Tehila Tuiloa and Malakai Ebenezer Tuiloa. I hope this thesis will instill in them the desire to continue pursuing their education. As Nelson Mandela once said and I quote “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this thesis owes so much from the support of several people and organisations. -

Tuesday-27Th November 2018

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DAILY HANSARD TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 [CORRECTED COPY] C O N T E N T S Pages Minutes … … … … … … … … … … 10 Communications from the Chair … … … … … … … 10-11 Point of Order … … … … … … … … … … 11-12 Debate on His Excellency the President’s Address … … … … … 12-68 List of Speakers 1. Hon. J.V. Bainimarama Pages 12-17 2. Hon. S. Adimaitoga Pages 18-20 3. Hon. R.S. Akbar Pages 20-24 4. Hon. P.K. Bala Pages 25-28 5. Hon. V.K. Bhatnagar Pages 28-32 6. Hon. M. Bulanauca Pages 33-39 7. Hon. M.D. Bulitavu Pages 39-44 8. Hon. V.R. Gavoka Pages 44-48 9. Hon. Dr. S.R. Govind Pages 50-54 10. Hon. A. Jale Pages 54-57 11. Hon. Ro T.V. Kepa Pages 57-63 12. Hon. S.S. Kirpal Pages 63-64 13. Hon. Cdr. S.T. Koroilavesau Pages 64-68 Speaker’s Ruling … … … … … … … … … 68 TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 The Parliament resumed at 9.36 a.m., pursuant to adjournment. HONOURABLE SPEAKER took the Chair and read the Prayer. PRESENT All Honourable Members were present. MINUTES HON. LEADER OF THE GOVERNMENT IN PARLIAMENT.- Madam Speaker, I move: That the Minutes of the sittings of Parliament held on Monday, 26th November 2018, as previously circulated, be taken as read and be confirmed. HON. A.A. MAHARAJ.- Madam Speaker, I beg to second the motion. Question put Motion agreed to. COMMUNICATIONS FROM THE CHAIR Welcome I welcome all Honourable Members to the second sitting day of Parliament for the 2018 to 2019 session. -

Is Fiji Ready for a Free Press

VOLUME 17. No.1I/MAY, 2012 ISSN 1029-7316 Pageant scrutiny by EDWARD TAVANAVANUA and PARIJATA GURDAYAL scheduled for the panel to view and assess the contestants. Hoerder, who has experience as HE Miss World Fiji 2012 Pageant is under a Miss Hibiscus judge, said the fact that they scrutiny following a plethora of allegations, only had one meeting with the contestants including that the winner was pre-deter- T was extremely irregular. The assessment also mined well before the judging panel deliberated. was confined to their life story or experiences. Although the pageant concluded about two Blake has since confirmed in a press state- weeks ago, the Miss World Organisation has ment that no judging criteria or points system yet to add the winner of the Fiji franchise, was used to judge the contestants. Torika Watters, to the list of winners on its official “If you are asked to be a judge for Miss World, website. The organisation has yet to respond to then you should come with the mindset of hear- queries e-mailed to it last week. Extra ing genuine stories and not with the expecta- Fiji franchise director Andhy Blake refused requests tions of age, point’s tabulation,” he said. yards for an in-person interview. When asked over the phone He added that based on this fact that no judging whether Watters had been accepted into the interna- or points system was employed, any allegations of pay off tional competition, he said “it’s a surprise”. judging being rigged are false. He also declined to comment on whether the funds “I gave my own personal opin- raised from a charity ball, which was held to create ions on whoever I saw fitting for awareness on mental health, had been given to St Giles the title without influencing the Hospital. -

The Diversity of Fijian Polities

7 The Diversity of Fijian Polities An overall discussion of the general diversity of traditional pan-Fijian polities immediately prior to Cession in 1874 will set a wider perspective for the results of my own explorations into the origins, development, structure and leadership of the yavusa in my three field areas, and the identification of different patterning of interrelationships between yavusa. The diversity of pan-Fijian polities can be most usefully considered as a continuum from the simplest to the most complex levels of structured types of polity, with a tentative geographical distribution from simple in the west to extremely complex in the east. Obviously I am by no means the first to draw attention to the diversity of these polities and to point out that there are considerable differences in the principles of structure, ranking and leadership between the yavusa and the vanua which I have investigated and those accepted by the government as the model. G.K. Roth (1953:58–61), not unexpectedly as Deputy Secretary of Fijian Affairs under Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, tended to accord with the public views of his mentor; although he did point out that ‘The number of communities found in a federation was not the same in all parts of Fiji’. Rusiate Nayacakalou who carried out his research in 1954, observed (1978: xi) that ‘there are some variations in the traditional structure from one village to another’. Ratu Sukuna died in 1958, and it may be coincidental that thereafter researchers paid more emphasis to the differences I referred to. Isireli Lasaqa who was Secretary to Cabinet and Fijian Affairs was primarily concerned with political and other changes in the years before and after independence in 1970. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Wansolwara, September 2011, 16(2)

Volume 16, No. 2 SEPTEMBER, 2011 Wansolwara An independent student newspaper and online publication Youth fund Report moots regional initiative to resolve lack of progress with the opportunities to associations to address the to the formal curriculum and by PARIJATA GURDAYAL propose projects that have a various youth issues. involve working closely with THERE is a need for a regional strong community focus. “Specifi c projects could be partners in the community, youth fund to provide youths “The absence of available funded to improve female and such as local government and with the needed resources to resources is a major reason male access to higher levels of church groups, it noted. INSIGHT address their issues. for the lack of progress at the education or basic literacy, or An alternative was for the This was one of the recom- regional country level in ad- providing more educational projects to be proposed and FORESTS are vital for the mendations in the State of Pa- dressing youth issues,” it said. or livelihood opportunities run by youth-led associations security of Pacifi c Island cifi c Youth 2011: Opportuni- The report proposes a for young people with HIV & that involve school leavers. ties and Obstacles report that system for addressing this gap AIDS, or physical or mental “The creation of links be- nations. Is enough being was released by the Secretar- through a regional agency such disabilities,” it said. tween communities should be iat of the Pacifi c Community as the SPC to set up a regional To attain a stronger commu- an important focus to lift the done to protect it? (SPC) and the United Nations youth challenge fund. -

Govt Investment Brings Better Teaching Experience

WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 6, 2019 l 16 PAGES l ISSUE 22 VOL 10 l WWW.FIJI.GOV.FJ j Fijij FocusDISCIPLINED TOP FIJIAN ENVOY TELLS SERVICES OF EDUCATION REMEMBER FALLEN 6 EMPOWERMENT SAVING 12 DAYLIGHT NOV 10, 2019 COMRADES Govt investment brings better teaching experience Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama with Nabukaluka District School students after opening the newly-built teacher’s quarters in Naitasiri. Photo: EMI KOROITANOA EDUCATION EMI KOROITANOA their own well-being, teachers can focus on The Head of Government said an unprece- maritime regions as their facilities –includ- REVOLUTIONtheir work in the classroom,” he said. dented $13.8 million has been allocated to- ing teachers’ quarters – were noticeably HE education revolution in Fiji is on Prime Minister Bainimarama, while open- wards location allowances for primary and shabbier than schools in urban areas,” PM track as the Government continues ing the newly-built teacher’s quarters at secondary teachers in remote areas. Bainimarama said. Tto invest in infrastructure to improve Nabukaluka District School in Naitasiri In the current budget cycle, Fijian Govern- “On top of that, the allowance we paid to not just learning but the teaching experi- recently, said those days of poor working ment has included early childhood educa- remote teachers was much lower than to- ence as well. conditions have been brought to an end by tion (ECE) teachers in the initiative for the day. As a result, life was made unduly dif- This as Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimara- Fijian Government. first time with an allocation of $500,000 for ficult for rural teachers and the top teaching ma opened a series of teachers’ quarters in This new energy, he said, will be felt by their location allowances. -

Indigenous Itaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr

Indigenous iTaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo Illustration by Cecelia Faumuina Author Dr Tarisi Vunidilo Tarisi is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, where she teaches courses on Indigenous museology and heritage management. Her current area of research is museology, repatriation and Indigenous knowledge and language revitalization. Tarisi Vunidilo is originally from Fiji. Her father, Navitalai Sorovi and mother, Mereseini Sorovi are both from the island of Kadavu, Southern Fiji. Tarisi was born and educated in Suva. Front image caption & credit Name: Drua Description: This is a model of a Fijian drua, a double hulled sailing canoe. The Fijian drua was the largest and finest ocean-going vessel which could range up to 100 feet in length. They were made by highly skilled hereditary canoe builders and other specialist’s makers for the woven sail, coconut fibre sennit rope and paddles. Credit: Commissioned and made by Alex Kennedy 2002, collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE011790. Link: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/648912 Page | 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: PREHISTORY OF FIJI .............................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3: ITAUKEI SOCIAL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... -

Fijian Colonial Experience: a Study of the Neotraditional Order Under British Colonial Rule Prior to World War II, by Timothy J

Chapter 4 The new of The more able Fij ian chiefs did not need to fetch up the glory of their ancestors to maintain leadership of their people: they exploited a variety of opportunities open to them within the Fij ian Administration. Ultimately colonial rule itself rested on the loyalty chosen chiefs could still command from their people, and day-to-day village governance, it has been seen, totally depended on them. Far from degenerating into a decadent elite, these chiefs devised a mode of leadership that was neither traditional, for it needed appointment from the Crown, nor purely administrative. Its material rewards came from salary and fringe benefits; its larger satisfactions from the extent to which the peopl e rallied to their leadership and voluntarily participated in the great celebrations of Fijian life , the traditional-type festivals of dance, food and ceremony that proclaimed to all: the people and the chief and the land are one . 'Government-work' had its place, but for chiefs and people there were always 'higher' preoccupations growing out of the refined cultural legacy of the past (albeit the attenuated past) which gave them all that was still distinctively Fij ian in their threatened way of life. This chapter will illuminate the ambiguous mix of constraint and opportunity for chiefly leadership in the colonial context as exercised prior to World War II by some powerful personalities from different status levels in the neotraditional order. Thurston's enthusiastic tax gatherer, Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi , was perhaps the most able of them , and in his happier days was generally esteemed as one of the finest of 'the old school' of chiefs . -

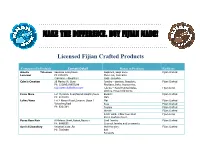

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Filling the Gaps: Identifying Candidate Sites to Expand Fiji's National Protected Area Network

Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20-21 September 2010 Stacy Jupiter1, Kasaqa Tora2, Morena Mills3, Rebecca Weeks1,3, Vanessa Adams3, Ingrid Qauqau1, Alumeci Nakeke4, Thomas Tui4, Yashika Nand1, Naushad Yakub1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 2 National Trust of Fiji 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 4 SeaWeb Asia-Pacific Program This work was supported by an Early Action Grant to the national Protected Area Committee from UNDP‐GEF and a grant to the Wildlife Conservation Society from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (#10‐94985‐000‐GSS) © 2011 Wildlife Conservation Society This document to be cited as: Jupiter S, Tora K, Mills M, Weeks R, Adams V, Qauqau I, Nakeke A, Tui T, Nand Y, Yakub N (2011) Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network. Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20‐21 September 2010. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji, 65 pp. Executive Summary The Fiji national Protected Area Committee (PAC) was established in 2008 under section 8(2) of Fiji's Environment Management Act 2005 in order to advance Fiji's commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA). To date, the PAC has: established national targets for conservation and management; collated existing and new data on species and habitats; identified current protected area boundaries; and determined how much of Fiji's biodiversity is currently protected through terrestrial and marine gap analyses.