Labour Courts in Europe: Proceedings of a Meeting Organised by The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional/Judicial Resistance to European Law in Iceland. Sovereignty and Constitutional Identity Vs. Access to Justice Under the EEA Agreement

Constitutional/judicial resistance to European Law in Iceland. Sovereignty and constitutional identity vs. access to justice under the EEA Agreement Professor M. Elvira MENDEZ-PINEDO1 Abstract In the context of occasional constitutional resistance to international and European Union (EU) law in other countries, we find a similar tension in Iceland vis-à-vis the European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement and the Icelandic constitutional/statutory domestic system (EEA Act 2/1993). The authority and effectiveness of EEA law seem disregarded with negative consequences for the judicial protection of individual rights. The EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) sent official letters to Iceland in 2015, 2016 and 2017. In its view, in too many recent cases, the Supreme Court has discarded and set aside validly implemented EEA law in order to give precedence to conflicting Icelandic law. In some cases, individuals have no proper remedy to exercise their European rights (State liability for judicial breaches of EEA law not admissible). It is uncertain at this time whether actions for infringement of EEA law will be brought by ESA to the EFTA Court. This study reviews this sort of judicial, legislative and/or constitutional resistance to EEA law in Iceland and argues that the use of concepts such as sovereignty (public international law) and constitutional identity (EU law) can never justify the denial of access to justice and effective judicial protection under the EEA Agreement. Keywords: Iceland, European Economic Area law, constitutional resistance, access to justice. JEL Classification: K10, K33, K40 1. Introduction The European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement2 extends the internal market and other EU policies to three non-EU neighbouring countries. -

Report of the Working Party on the Review of the Labour Tribunal

CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION .............................................................1 I. Establishment of the Working Party ................................................1 II. Background ......................................................................................1 III. The Work of the Working Party .......................................................2 IV. Scope of the Review.........................................................................3 V. The Report........................................................................................3 CHAPTER TWO – THE SET-UP, PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE OF THE LABOUR TRIBUNAL .......................................................................4 I. The Set-Up of the Tribunal ..............................................................4 A. Registry..................................................................................4 B. Tribunal Officers....................................................................4 C. Presiding Officers ..................................................................5 II. The Staffing and Location of the Tribunal.......................................6 III. Jurisdiction of the Tribunal ..............................................................6 IV. Processing of Claims in the Tribunal ...............................................8 A. Filing Claims..........................................................................8 B. Inquiries by Tribunal Officers................................................8 C. Hearings in -

Mimetic Evolution. New Comparative Perspectives on the Court of Justice of the European Union in Its Federal Judicial Architecture

Mimetic Evolution. New Comparative Perspectives on the Court of Justice of the European Union in its Federal Judicial Architecture Leonardo Pierdominici Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Laws of the European University Institute Florence, 29 February 2016 European University Institute Department of Law Mimetic Evolution. New Comparative Perspectives on the Court of Justice of the European Union in its Federal Judicial Architecture Leonardo Pierdominici Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Laws of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Loïc Azoulai, European University Institute Prof. Bruno De Witte, European University Institute Prof. Giuseppe Martinico, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna - Pisa Prof. Laurent Pech, Middlesex University London ©Title Leonardo Name Pierdominici,Surname, Institution 2015 Title Name Surname, Institution No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of Law – LL.M. and Ph.D. Programmes I Leonardo Pierdominici certify that I am the author of the work “Mimetic Evolution. New Comparative Perspectives on the Court of Justice of the European Union in its Federal Judicial Architecture” I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. -

National Risk Assessment

2019 National Risk Assessment Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing National Commissioner of the Icelandic Police 1 April 2019 National Risk Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Table of Contents Preface Infrastructure Legal environment, police services, and monitoring Methodology Consolidated conclusions Risk classification summary Predicate offences Cash Company operations Financial market Specialists Gambling Trade and services Other Terrorist financing References 2 Preface Iceland is probably not the first country coming to mind when most people discuss money laundering and terrorist financing. In an increasingly globalised world, however, Iceland is nowhere near safe against the risks that money laundering and terrorist financing entail. Nor is it exempt from a duty to take appropriate and necessary measures to prevent such from thriving in its area of influence. In September 1991, Iceland entered into collaboration with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which is an international action group against money laundering and terrorist financing. FATF has issued instructions on the measures member states shall take in response to the threat stemming from money laundering and terrorist financing. FATF's instructions have become global guidelines. For example, the European Union's directives have been in accordance with these guidelines. By joining FATF, Iceland obligated itself to coordinating its legislation with the action group's instructions. Regarding this, FATF's evaluation in 2017-2018 revealed various weaknesses in the Icelandic legislation. Iceland began responding, which, for example, entailed legalising the European Union's 4th Anti-money Laundering Directive. In accordance with the requirements following from FATF Recommendation no. 1, the above directive assumes that all member states shall carry out a risk assessment of the main threats and weaknesses stemming from money laundering and terrorist financing within the areas each member state controls. -

The European Protection Order for Victims > Criminal Judicial Cooperation and Gender-Based Violence

Información ORGANISING COMMITTEE Palau de Pineda UIMP courses in Valencia are 4 Plaza del Carmen, 4 Manuel de Lorenzo Segrelles, Bar Association of Valencia. 46003 Valencia validated by elective credits International Congress Gemma Gallego Sánchez, Judge, former member of the General Tel. +34 963 108 020 / 019 / 018 in public universities Fax: +34 963 108 017 of the Valencian Community. Council of the Judiciary of Spain. Administrative Secretary opening hours*: Check with the home Elena Martínez García, Senior Lecturer of Procedural Law, University 10,00 - 13,30 h. university the number of Thursday: credits recognised of Valencia. 16,30 - 18,00 h. The European Protection Order for Laura Román, Senior Lecturer of Constitutional Law, Rovira i Virgili * CLOSED AUGUST 1st TO 24th Victims University, Epogender porject. The registration gives the The registration period for the congress right to obtain Criminal judicial cooperation and gender-based is o p e n until the b e g inning o f the s e m ina r a certificate of attendance while places are still available. (a tte n d a n c e violence SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE at more than 85% of Registration fees: Beatriz Belando Garín, Senior Lecturer of Administrative Law, sessions). University of Valencia. - 75 euros (55 euros academic fees + 20 euros secretary fees) for students Christoph Burchard, Lecturer, Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, enroled in all the universities of the Germany. Valencian Community. Directors: Elisabet Cerrato, Lecturer of Procedural Law, Rovira i Virgili University, - 108 euros (88 euros academic fees Teresa Freixes Sanjuán Epogender project. + 20 euros secretary fees) for students Elena Martínez García Laura Ervo, Professor of Procedural Law, Örebro University, Sweden. -

Resolving Individual Labour Disputes: a Comparative Overview

Resolving Individual Labour Disputes A comparative overview Edited by Minawa Ebisui Sean Cooney Colin Fenwick Resolving individual labour disputes Resolving individual labour disputes: A comparative overview Edited by Minawa Ebisui, Sean Cooney and Colin Fenwick International Labour Office, Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2016 First published 2016 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Ebisui, Minawa; Cooney, Sean; Fenwick, Colin F. Resolving individual labour disputes: a comparative overview / edited by Minawa Ebisui, Sean Cooney, Colin Fenwick ; International Labour Office. - Geneva: ILO, 2016. ISBN 978-92-2-130419-7 (print) ISBN 978-92-2-130420-3 (web pdf ) International Labour Office. labour dispute / labour dispute settlement / labour relations 13.06.6 ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Commdh(2005)10 Original Version

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS _______________ BUREAU DU COMMISSAIRE AUX DROITS DE L´HOMME Strasbourg, 14 December 2005 CommDH(2005)10 Original version REPORT BY Mr. ALVARO GIL-ROBLES, COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, ON HIS VISIT TO THE REPUBLIC OF ICELAND 4 - 6 JULY 2005 for the attention of the Committee of Ministers and the Parliamentary Assembly CommDH(2005)10 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................3 GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ..................................................................................................4 1. JUDICIARY ....................................................................................................................5 2. PRISON SYSTEM ..........................................................................................................7 3. PRE-TRIAL DETENTION............................................................................................8 4. HUMAN RIGHTS STRUCTURES.............................................................................10 5. TREATMENT OF ASYLUM SEEKERS..........................................................................12 6. INTEGRATION OF FOREIGNERS.................................................................................14 7. GENDER EQUALITY AND VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN ....................................16 8. NON-DISCRIMINATION..................................................................................................18 9. TRAFFICKING -

Report to the Spanish Government on the Visit to Spain Carried out by The

CPT/Inf (2013) 6 Report to the Spanish Government on the visit to Spain carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 31 May to 13 June 2011 The Spanish Government has requested the publication of this report and of its response. The Government’s response is set out in document CPT/Inf (2013) 7. Strasbourg, 30 April 2013 - 2 - CONTENTS Copy of the letter transmitting the CPT’s report............................................................................5 I. INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................6 A. Dates of the visit and composition of the delegation ..............................................................6 B. Establishments visited...............................................................................................................7 C. Consultations held by the delegation.......................................................................................9 D. Co-operation between the CPT and the authorities of Spain ...............................................9 E. Immediate observations under Article 8, paragraph 5, of the Convention .......................10 II. FACTS FOUND DURING THE VISIT AND ACTION PROPOSED ..............................11 A. Law enforcement agencies......................................................................................................11 1. Preliminary remarks ........................................................................................................11 -

Constitutional Bill

Revised translation 11.12.2012 by Anna Yates, certified translator Constitutional Bill for a new constitution for the Republic of Iceland From the majority of the Constitutional and Supervisory Committee (VBj, ÁI, RM, LGeir, MSch, MT). Preamble We, the people of Iceland, wish to create a just society with equal opportunities for everyone. Our different origins enrich the whole, and together we are responsible for the heritage of the generations, the land and history, nature, language and culture. Iceland is a free and sovereign state which upholds the rule of law, resting on the cornerstones of freedom, equality, democracy and human rights. The government shall work for the welfare of the inhabitants of the country, strengthen their culture and respect the diversity of human life, the land and the biosphere. We wish to promote peace, security, well-being and happiness among ourselves and future generations. We resolve to work with other nations in the interests of peace and respect for the Earth and all Mankind. In this light we are adopting a new Constitution, the supreme law of the land, to be observed by all. Chapter I. Foundations Article 1 Form of government Iceland is a Republic governed by parliamentary democracy. 1 Article 2 Source and holders of state powers All state powers spring from the nation, which wields them either directly, or via those who hold government powers. The Althing holds legislative powers. The President of the Republic, Cabinet Ministers and the State government and other government authorities hold executive powers. The Supreme Court of Iceland and other courts of law hold judicial powers. -

How Informal Justice Systems Can Contribute

United Nations Development Programme Oslo Governance Centre The Democratic Governance Fellowship Programme Doing Justice: How informal justice systems can contribute Ewa Wojkowska, December 2006 United Nations Development Programme – Oslo Governance Centre Contents Contents Contents page 2 Acknowledgements page 3 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations page 4 Research Methods page 4 Executive Summary page 5 Chapter 1: Introduction page 7 Key Definitions: page 9 Chapter 2: Why are informal justice systems important? page 11 UNDP’s Support to the Justice Sector 2000-2005 page 11 Chapter 3: Characteristics of Informal Justice Systems page 16 Strengths page 16 Weaknesses page 20 Chapter 4: Linkages between informal and formal justice systems page 25 Chapter 5: Recommendations for how to engage with informal justice systems page 30 Examples of Indicators page 45 Key features of selected informal justice systems page 47 United Nations Development Programme – Oslo Governance Centre Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I am grateful for the opportunity provided by UNDP and the Oslo Governance Centre (OGC) to undertake this fellowship and thank all OGC colleagues for their kindness and support throughout my stay in Oslo. I would especially like to thank the following individuals for their contributions and support throughout the fellowship period: Toshihiro Nakamura, Nina Berg, Siphosami Malunga, Noha El-Mikawy, Noelle Rancourt, Noel Matthews from UNDP, and Christian Ranheim from the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights. Special thanks also go to all the individuals who took their time to provide information on their experiences of working with informal justice systems and UNDP Indonesia for releasing me for the fellowship period. Any errors or omissions that remain are my responsibility alone. -

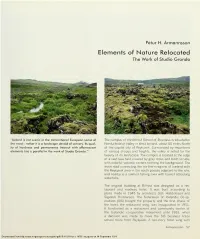

Elements of Nature Relocated the Work of Studio Granda

Petur H. Armannsson Elements of Nature Relocated The Work of Studio Granda "Iceland is not scenic in the conventional European sense of The campus of the Bifrost School of Business is situated in the word - rather it is a landscape devoid of scenery. Its qual- Nordurardalur Valley in West Iceland, about 60 miles North ity of hardness and permanence intercut v/\1\-i effervescent of the capital city of Reykjavik. Surrounded by mountains elements has a parallel in the work of Studio Granda/" of various shapes and heights, the valley is noted for the beauty of its landscape. The campus is located at the edge of a vast lava field covered by gray moss and birch scrubs, w/ith colorful volcanic craters forming the background. The main road connecting the northern regions of Iceland with the Reykjavik area in the south passes adjacent to the site, and nearby is a salmon-fishing river with tourist attracting waterfalls. The original building at Bifrost was designed as a res- taurant and roadway hotel. It was built according to plans made in 1945 by architects Gisli Halldorsson and Sigvaldi Thordarson. The Federation of Icelandic Co-op- eratives (SIS) bought the property and the first phase of the hotel, the restaurant wing, was inaugurated in 1951. It functioned as a restaurant and community center of the Icelandic co-operative movement until 1955, when a decision was made to move the SIS business trade school there from Reykjavik. A two-story hotel wing with Armannsson 57 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/thld_a_00361 by guest on 24 September 2021 hotel rooms was completed that same year and used as In subsequent projects, Studio Granda has continued to a student dormitory in the winter. -

THE PLACE of the EMPLOYMENT COURT in the NEW ZEALAND JUDICIAL HIERARCHY Paul Roth*

233 THE PLACE OF THE EMPLOYMENT COURT IN THE NEW ZEALAND JUDICIAL HIERARCHY Paul Roth* This article considers the status of the Employment Court and its position in the overall court structure in New Zealand. It examines the issue from both an historical and comparative New Zealand legal perspective. Professor Gordon Anderson has written much on the Employment Court and its predecessors. He championed its independent existence as a specialist court1 when it was under sustained attack in the 1990s by the Business Roundtable and New Zealand Employers' Federation (both now absorbed by 2 3 or transformed into different organisations), and by some in the then National government. The * Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Otago. 1 See Gordon Anderson A Specialist Labour Law Jurisdiction? An Assessment of the Business Roundtable's Attack on the Employment Court (Gamma Occasional Paper 5, 1993); Gordon Anderson "Specialist Employment Law and Specialist Institutions" (paper presented to the New Zealand Institute of Industrial Relations Research Seminar on the Future of the Employment Court and the Employment Tribunal, 23 April 1993); Gordon Anderson "The Judiciary, the Court and Appeals" [1993] ELB 90; and Gordon Anderson "Politics, the Judiciary and the Court – Again" [1995] ELB 2. 2 See New Zealand Business Roundtable and New Zealand Employers' Federation A Study of the Labour- Employment Court (December 1992); Colin Howard Interpretation of the Employment Contracts Act 1991 (New Zealand Business Roundtable and New Zealand Employers Federation, June 1996); Bernard Robertson The Status and Jurisdiction of the New Zealand Employment Court (New Zealand Business Roundtable, August 1996); and Charles W Baird "The Employment Contracts Act and Unjustifiable Dismissal: The Economics of an Unjust Employment Tax" (New Zealand Business Roundtable and New Zealand Employers Federation, August 1996).