AIDA DE 2018Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Schadstoff-Sammlung 2021 (Fahrplan)

Mobile Schadstoff-Sammlung 2021 (Fahrplan) Frühjahr Herbst Ort Straße / Platz Uhrzeit 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Neuenkirchen Schützenplatz 10:15-11:45 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Brochdorf Parkplatz Schützenhaus 12:00-12:15 Gefahrstoffsymbole 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Schwalingen vor ehem. Gasthaus von Fintel 12:30-13:00 Es handelt sich um Zeichen, 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Sprengel Nähe Landgasthaus zur Sprengeler Mühle 14:00-14:15 die auf gefährliche Inhalts- 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Schülern Sportplatz, Alter Schulweg 14:30-14:45 stoffe hinweisen. Diese 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Hemsen/Langeloh Kleinsporthalle Hemsen, Hemsener Weg 15:00-15:15 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Wolterdingen Friedhof 15:45-16:30 zum Beispiel auf den 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Soltau, Friedrichseck Freizeitverein Friedrichseck 16:45-17:15 26.04.2021 01.11.2021 Harber Feuerwehrgerätehaus 17:30-18:00 Behältern von Farben, Frühjahr Herbst Ort Straße / Platz Uhrzeit Lacken und Lösungsmitteln. 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Wietzendorf Kampstraße, LBAG 10:15-11:30 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Reiningen Gasthaus Brammer 11:45-12:00 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Trauen Pommernweg Ecke Soldiner Str. 12:45-13:15 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Oerrel Feuerwehrgerätehaus 13:30-14:00 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Breloh Feuerwehrgerätehaus 14:30-15:15 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Munster Parkpl. Grundschule Hanloh, Alvermanns Grund 15:30-17:30 27.04.2021 02.11.2021 Ilster/Alvern/Töpingen Parkplatz Heidkrug, an der B 71 17:45-18:00 umweltgefährlich Frühjahr Herbst Ort Straße / Platz Uhrzeit 28.04.2021 03.11.2021 Wintermoor Kreuzung Am Sportplatz / Vor den -

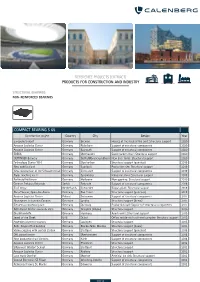

Reference List Construction and Industry

REFERENCE PROJECTS (EXTRACT) PRODUCTS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY STRUCTURAL BEARINGS NON-REINFORCED BEARINGS COMPACT BEARING S 65 Construction project Country City Design Year Europahafenkopf Germany Bremen Houses at the head of the port: Structural support 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Paderborn Support of structural components 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Bayreuth Support of structural components 2020 EDEKA Germany Oberhausen Supermarket chain: Structural support 2020 OETTINGER Brewery Germany Gotha/Mönchengladbach New beer tanks: Structural support 2020 Technology Center YG-1 Germany Oberkochen Structural support (punctual) 2019 New nobilia plant Germany Saarlouis Production site: Structural support 2019 New construction of the Schwaketenbad Germany Constance Support of structural components 2019 Paper machine no. 2 Germany Spremberg Industrial plant: Structural support 2019 Parkhotel Heilbronn Germany Heilbronn New opening: Structural support 2019 German Embassy Belgrade Serbia Belgrade Support of structural components 2018 Bio Energy Netherlands Coevorden Biogas plant: Structural support 2018 NaturTheater, Open-Air-Arena Germany Bad Elster Structural support (punctual) 2018 Amazon Logistics Center Poland Sosnowiec Support of structural components 2017 Novozymes Innovation Campus Denmark Lyngby Structural support (linear) 2017 Siemens compressor plant Germany Duisburg Production hall: Support of structural components 2017 DAV Alpine Centre swoboda alpin Germany Kempten (Allgäu) Structural support 2016 Glasbläserhöfe -

Asylum-Seekers Become the Nation's Scapegoat

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 14 Number 2 Volume 14, Numbers 2 & 3, 1993 Article 7 1993 TURMOIL IN UNIFIED GERMANY: ASYLUM-SEEKERS BECOME THE NATION'S SCAPEGOAT Patricia A. Mollica Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mollica, Patricia A. (1993) "TURMOIL IN UNIFIED GERMANY: ASYLUM-SEEKERS BECOME THE NATION'S SCAPEGOAT," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 14 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol14/iss2/ 7 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. TURMOIL IN UNIFIED GERMANY: ASYLUM-SEEKERS BECOME THE NATION'S SCAPEGOAT I. INTRODUCTION On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, symbolizing the end of a divided German state. The long dreamed-of unification finally came to its fruition. However, the euphoria experienced in 1989 proved ephemeral. In the past four years, Germans have faced the bitter ramifications of unity. The affluent, capitalist West was called on to assimilate and re-educate the repressed communist East. Since unification, Easterners have been plagued by unemployment and a lack of security and identity, while Westerners have sacrificed the many luxuries to which they have grown accustomed. A more sinister consequence of unity, however, is the emergence of a violent right-wing nationalist movement. Asylum- seekers and foreigners have become the target of brutal attacks by extremists who advocate a homogenous Germany. -

Hannover Hbf – Soltau (Han) – Hamburg-Harburg RB38

Hamburg Buxtehude Cuxhaven HarHarr RB38 Winsen (Luhe) Lüneburg Bchhol Nordheide Uelzen Bremen Suerhop Holm-Seppensen Büsenbachtal Handeloh RB38 Wintermoor HVV - Hamburger Verkehrsverbund Hannover Hbf – Soltau (Han) – Hamburg-Harburg Schneverdingen RB38 Wolterdingen (Han) Hamburg Buxtehude Soltau Nord Hamburg-Harburg Cuxhaven RB38 HarHarr Bus von Soltau Sola Han nach Bispingen RB38 Dorfmark Buchholz (Nordheide) Winsen (Luhe) Suerhop Lüneburg Bchhol Nordheide Uelzen Tarifausweitung des HVV ab 15.12.2019: Holm-Seppensen Walsrode Bad Fallingbostel Bremen Der HVV wird größer und gilt künftig bis Uelzen, Büsenbachtal Suerhop Soltau und Cuxhaven. Handeloh Holm-Seppensen Hodenhagen Dadurch verändern sich die Zonen und Ringe RB38 Büsenbachtal NEU HVV-Einzel-, Wintermoor Handeloh RB38 auf der Strecke der RB38 an den Bahnhöfen Tages- und Zeit- Wolterdingen, Soltau Nord und Soltau (Han). karten Ring E Schneverdingen RB38 Wintermoor NEU HVV-Einzel-, Wolterdingen (Han) Schwarmstedt • Verschiebung von Ring E nach F Tages- und Zeit- Schneverdingen karten Ring F Soltau Nord • Veränderung der Zonen-Nummern: Wolter- Lindwedel dingen, Soltau Nord und Soltau (Han) 838 -> Wolterdingen (Han) RB38 Soltau (Han) NEU HVV-Einzel-, Mellendorf 1028 Dorfmark Tages- und Zeit- Soltau Nord karten Ring F Bitte lassen Sie Ihre Zeitkarte ggf. in einer der Bus von Soltau Walsrode Bad Fallingbostel Hannover Sola Han nach Bispingen RB38 Servicestellen oder Ihr ProfiTicket bei Ihrem Dorfmark Flughafen Arbeitgeber ändern. Weitere Informationen un- Tarifinfos:Hodenhagen anenhaen -

VERMILION VOR ORT 000 000 00 Fachinformation 00 60 60 00 0 000 50 50 59 59

0 3300000 3350000 3400000 3450000 3500000 3550000 3600000 3650000 3700000 3750000 3800000 3850000 3900000 3950000 00 000 00 00 61 61 000 50 60 6050000 VERMILION VOR ORT 000 000 00 Fachinformation 00 60 60 0 00 000 50 50 59 59 Information zum Vorhaben Erdgaserkundung im Raum Bad Fallingbostel 0 000 Region Heidekreis 00 590000 59 Energieregion Niedersachsen: Heimisches Erdgas für eine zuverlässige Versorgung 0 0 00 50 Niedersachsen spielt bei der Deckung des Gasbedarfs in Deutschland eine zen- 585000 58 trale Rolle: Über 95 % des bundesweit produzierten Erdgases stammen aus Nieder- 0 sachsen. Damit trägt das Land ganz wesentlich zur sicheren Energieversorgung in 0 00 00 Deutschland und der Region bei. Abb. 1 zeigt die bekannten Erdgas- und Erdöllager580000 - 58 stätten in Niedersachsen. 0 0 00 50 Erdgasförderung in der Region Heidekreis 575000 57 Abb. 1 Erdgas- und Erdölfelder in Niedersachsen 0 In der Region Heidekreis wird bereits seit mehr als 50 Jahren Erdgas gefördert und Staatsgrenze Erdgaslagerstätten 0 00 00 sie verfügt noch heute über reiche Erdgasvorkommen. Seit Beginn der ersten Bohr-570000 Niedersachsen Erdöllagerstätten 57 aktivitäten im Jahr 1906 wurden im Landkreis 456 Bohrungen abgeteuft, davon 99 3300000 3350000 3400000 3450000 3500000 3550000 3600000 3650000 3700000 3750000 3800000 3850000 3900000 3950000 Allgemein Kohlenwasserstoff Felder 0840 0 Ablenkungen Untertage, die man Obertage nicht sieht. Etwa 300 dieser Bohrungen Kilometer Staatsgrenze Gas KohlenwasserstoffBommelsen Z1 Felder Niedersachen NÖl sind Erdölbohrungen, die übrigen Erdgasbohrungen. Größere Funde reichen von Bundesländer Visselhövedein Norddeutschland dem Erdölfeld Hansa im Jahr 1942 bis zum Erdgasfeld Idsingen im Jahr 1996. Weite- Soltau Date: 2017/03/16 Edited by: P.-F. -

Libellenkartierung Im Landkreis Deggendorf (Niederbayern)

©Ges. deutschspr. Odonatologen e.V.; download www.libellula.org/libellula/ und www.zobodat.at Libellula 13 (1/2), 9-31 1994 Libellenkartierung im Landkreis Deggendorf (Niederbayern) Bahram Gharadjedaghi eingegangen: 31. August 1993 Summary In the district Deggendorf, Lower Bavaria, 39 dragonfly species have been found. Evidence of 36 species comes from a mapping of 48 research areas in the district in 1990 as well as from the analysis of recent observations of other persons. 19 species are important for nat ure conservation in the district. 21 of the recorded species are listed in the Bavarian List of Endangered Species, two of them are irregular guests in Bavaria. The investigated area is comparatively species-rich with regard to dragonflies, but there are clear differences in the diverse parts of the district. Especially the gravel pits and dead arms of the Isar and the Danube are suitable biotopes for dragonflies, many species, amongst them endangered ones, are quiet abundant, e.g. the Erythromma-spec- ies. The occurence of Gomphus vulgatissimus in these parts is of great importance, while at the mostly natural low-mountain streams the presence of the very endangered Ophiogomphus cecilia is of special interest. In the more agricultural south-west range of the district only few dragonfly-habitats and remarkable species are found. The state of the dragonfly-populations with regard to the different species is shown. The causes for the endangerment of dragonflies in the district and the necessary protective measures are given and discussed. Keywords: dragonfly habitats, district survey, germany, bavarian forest, danube river, endangered species, protection. -

Jugendherberge Bad Fallingbostel Bad Fallingbostel Per Bahn: Mit Der Bahn Erreichen Sie Den Bahnhof in Liethweg 1 Auf Zu Löns Und Löwen! Bad Fallingbostel

051.15.1404_HP_Fallingbostel_051.15._HP_BadFallingbostel 29.10.15 17:22 Seite 2 Willkommen in NIEDERSACHSEN Lüneburg Workshop, Tagung, Entspannung! Mitglied werden, Werte fördern! Hitzacker Für Tagungen halten wir Overheadprojektor, Leinwand, Jugendherbergen stehen allen offen – Menschen jeden Alters, Bispingen Beamer, Flipchart, Pinnwand, Fernsehgerät, DVD-Player und jeder ethnischen Herkunft und Weltanschauung, sind herzlich Uelzen einen Moderationskoffer bereit. Im großen Mehrzweckraum willkommen. Voraussetzung ist lediglich eine gültige DJH- Bad Fallingbostel Müden steht ein Klavier bereit, zur Abend- Mitgliedskarte bzw. DJH-Gruppenkarte. Mitglied werden Sie in oder Abschlussdisco kommt allen DJH-Geschäftsstellen und Jugendherbergen. So stehen Hankensbüttel unsere Musikanlage zum Ihnen nicht nur die deutschen Jugendherbergen und Youth Einsatz. Hostels weltweit offen, Sie unterstützen auch die völkerver- Celle bindende Idee des DJH. Mardorf Das große Außengelände lädt ein zu Spaß und Hannover Wolfsburg Weitere Informationen bekommen Sie unter: Spiel mit Tischtennis, www.djh-niedersachsen.de · Telefon 0511 16402-37 Braunschweig Beachvolleyballfeld und Hildesheim schönem Spielplatz. Fahr- Hameln Schöningen zeuge, Spielgeräte und Bodenwerder Sandspielzeug können gern Goslar entliehen werden. Hahnenklee Torfhaus Silberborn Braunlage Gute Reise, guten Appetit! Bad Sachsa Nach erholsamer Nacht mundet das reichhaltige Frühstücks- Göttingen büffet vorzüglich. Bei Halb- und Vollpension sind die Büffets Hann. Münden ebenfalls abwechslungsreich -

Members and Sponsors

LOWER SAXONY NETWORK OF RENEWABLE RESOURCES MEMBERS AND SPONSORS The 3N registered association is a centre of expertise which has the objective of strengthening the various interest groups and stakeholders in Lower Saxony involved in the material and energetic uses of renewable resources and the bioeconomy, and supporting the transfer of knowledge and the move towards a sustainable economy. A number of innovative companies, communities and institutions are members and supporters of the 3N association and are involved in activities such as the production of raw materials, trading, processing, plant technology and the manufacturing of end products, as well as in the provision of advice, training and qualification courses. The members represent the diversity of the sustainable value creation chains in the non-food sector in Lower Saxony. 3 FOUNDING MEMBER The Lower Saxony Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Con- Contact details: sumer Protection exists since the founding of the state of Niedersächsches Ministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz Lower Saxony in 1946. Calenberger Str. 2 | 30169 Hannover The competences of the ministry are organized in four de- Contact: partments with the following emphases: Ref. 105.1 Nachwachsende Rohstoffe und Bioenergie Dept 1: Agriculture, EU farm policy (CAP), agricultural Dr. Gerd Höher | Theo Lührs environmental policy Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dept 2: Consumer protection, animal health, animal Further information: www.ml.niedersachsen.de protection Dept 3: Spatial planning, regional development, support Dept 4: Administration, law, forests Activities falling under the general responsibility of the ministry are implemented by specific authorities as ‘direct’ state administration. -

Female Genital Mutilation & Asylum in the European Union

© UNHCR / J. Oatway 2009 FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION & ASYLUM IN THE EUROPEAN UNION A Statistical Update (March 2014)* Female genital mutilation is a human rights violation Female genital mutilation (FGM) includes procedures that [My Grandma] caught hold of me and gripped intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs my upper body. Two other women held my legs apart. for non-medical reasons. This harmful traditional practice is The man, who was probably an itinerant traditional most common in the western, eastern, and north-eastern circumciser from the blacksmith clan, picked up a pair regions of Africa; in some countries in Asia and the Middle of scissors. […] Then the scissors went down between East; and among migrant and refugee communities from my legs and the man cut off my inner labia and clitoris. these areas in Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and A piercing pain shot up between my legs, indescribable, the United States of America. and I howled. Then came the sewing: the long, blunt needle clumsily pushed into my bleeding outer labia, FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human my loud and anguished protests. [… My sister] Haweya rights of women and girls. The practice also violates a was never the same afterwards. She had nightmares, person’s rights to health, security and physical integrity; the and during the day began stomping off to be alone. My right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading once cheerful, playful little sister changed. Sometimes treatment; and the right to life when the procedure results in she just stared vacantly at nothing for hour.” death. -

Moving Beyond Crisis: Germany's New Approaches to Integrating

MOVING BEYOND CRISIS: GERMANY’S NEW APPROACHES TO INTEGRATING REFUGEES INTO THE LABOR MARKET By Victoria Rietig TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION MOVING BEYOND CRISIS Germany’s New Approaches to Integrating Refugees into the Labor Market By Victoria Rietig October 2016 Acknowledgments The author is grateful to the many experts in Berlin and Dresden who shared their expertise and time in interviews and email exchanges to inform this analysis—their contributions were invaluable. Thanks also go to Meghan Benton and Maria Vincenza Desiderio, Senior Policy Analysts at the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) and MPI Europe, who improved this report through their thoughtful review and comments on earlier drafts, and to Michelle Mittelstadt and the MPI Communications Team for their skillful edits. This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an MPI initiative, for its sixteenth plenary meeting, held in Toronto in June 2016. The meeting’s theme was “The Other Side of the Asylum and Resettlement Coin: Investing in Refugees’ Success along the Migration Continuum,” and this report was among those that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/ transatlantic. © 2016 Migration Policy Institute. -

POSTAKTUELL an Alle Haushalte

POSTAKTUELL an alle Haushalte Jahresbericht 2019 Seite Offenberg, im Februar 2020 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser unseres Jahresberichts, verehrte Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, zum Ende der laufenden Legislaturperiode möchte ich als Bürgermeister namens der Gemeinde Offenberg aber auch persönlich wieder einen Jah- resbericht vorlegen, aus dem die Arbeit der politischen Gemeinde, ihren Gremien, den kommunalen Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeitern sowie das Leben in unseren Ortsteilen des vergangenen Jahres hervorgeht. Im sichtbaren Fokus standen im vergangenen Jahr diverse Bauprojekte der Gemeinde: Die Sanierung und Erweiterung der gemeindlichen Bauhof- halle, die Planung eines neuen Kindergartens zur Erweiterung des Be- treuungsangebots für unsere kleinen Gemeindebürger, die Erschließung neuer Flächen für die Wohnbebauung und auch die interkommunale Zu- S. 28 sammenarbeit zur Sanierung und zum Betrieb der Mettener Kläranlage. Baugebiet „Steinbühl“ Finsing In der Bürgerversammlung im November 2019 konnte eine Vielfalt von Tätigkeiten und Aufgaben unserer Gemeinde vorgestellt werden. Wir wa- ren auch im zurückliegenden Jahr darauf bedacht, zum Wohle der Bür- gerschaft und unserer Gemeinde Entscheidungen zu treffen. Auch bauen wir Stück für Stück die kommunale Infrastruktur aus. Was die Gemeinde selbst betrifft, so haben wir im Rathaus eine neue EDV-Anlage installiert und den Bauhof mit zeitgemäßen Fahrzeugen und Maschinen ausgestat- tet. Die Vereine und Gruppen in der Gemeinde beteiligen sich recht rege am Ferienprogramm und gestalten je für sich ein gesellschaftliches und ansprechendes Vereinsleben. An dieser Stelle darf ich mich bei Ihnen allen für Ihre Unterstützung bedanken. Persönlich darf ich mich für das Vertrauen der letzten Jahre bedanken und freue mich im Rückblick auf die ablaufende Wahlperiode über die gemeindlichen Erfolge und um- gesetzten Projekte. -

Verantwortlicher Herausgeber: Landratsamt Deggendorf

Verantwortlicher Herausgeber: Landratsamt Deggendorf Erscheint nach Bedarf – Zu beziehen beim Landratsamt Deggendorf – Einzelbezugspreis € 1,00 Das Amtsblatt ist auch über das Internet unter www.landkreis-deggendorf.de abrufbar. Nr. 07/2006 Dienstag, 09.05.2006 Inhaltsangabe: Vollzug des Tierseuchengesetzes, der Geflügelpest-Verordnung und der Wildvogel-Geflügelpestschutzverordnung........................................... Seite 72 Verzeichnis der vom Landratsamt Deggendorf genehmigten Bauanträge in der Zeit vom 01.04.2006 bis 30.04.2006........................... Seite 82 Bekanntmachung der Haushaltssatzung des Schulverbandes Hauptschule Plattling für das Haushaltsjahr 2006..................................... Seite 85 Bekanntmachung über die „Bezeichneten Gebiete“ i. S. d. Art. 17 a Bayer. Wassergesetz des Landkreises Deggendorf für die Bereiche der Gemeinden Aholming, Außernzell, Grafling,Grattersdorf, Hengersberg, Hunding, Iggensbach, Künzing, Lalling, Metten, Niederalteich, Oberpöring, Schöllnach, Stephansposching, Wallerfing und Winzer................................................ Seite 87 Bekanntmachung über die Feststellung und Prüfung der Jahresabschlüsse 1997 bis 2001 des Zweckverbandes für Tierkörper- und Schlachtabfallbeseitigung Plattling...................................................... Seite 125 Bekanntmachungen der Sparkasse Deggendorf hier: Aufgebotsverfahren........................................................................... Seite 127 hier: Kraftloserklärung................................................................................