Conservation and Sustainability Management of Forest in Shimoga - Need for Policy Interventions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report

Karnataka Tourism Vision group 2014 report KARNATAKA TOURISM VISION GROUP (KTVG) Recommendations to the GoK: Jan 2014 Task force KTVG Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report 1 FOREWORD Tourism matters. As highlighted in the UN WTO 2013 report, Tourism can account for 9% of GDP (direct, indirect and induced), 1 in 11 jobs and 6% of world exports. We are all aware of amazing tourist experiences globally and the impact of the sector on the economy of countries. Karnataka needs to think big, think like a Nation-State if it is to forge ahead to realise its immense tourism potential. The State is blessed with natural and historical advantage, which coupled with a strong arts and culture ethos, can be leveraged to great advantage. If Karnataka can get its Tourism strategy (and brand promise) right and focus on promotion and excellence in providing a wholesome tourist experience, we believe that it can be among the best destinations in the world. The impact on job creation (we estimate 4.3 million over the next decade) and economic gain (Rs. 85,000 crores) is reason enough for us to pay serious attention to focus on the Tourism sector. The Government of Karnataka had set up a Tourism Vision group in Oct 2013 consisting of eminent citizens and domain specialists to advise the government on the way ahead for the Tourism sector. In this exercise, we had active cooperation from the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Mr. R.V. Deshpande; Tourism Secretary, Mr. Arvind Jadhav; Tourism Director, Ms. Satyavathi and their team. The Vision group of over 50 individuals met jointly in over 7 sessions during Oct-Dec 2013. -

Shimoga District at a Glance

FOREWORD Groundwater is an essential component of the environment and economy. It sustains the flow in our rivers and plays an important role in maintaining the fragile ecosystems. The groundwater dependence of agrarian states like Karnataka is high. Recent studies indicate that 26 percent of the area of Karnataka State is under over exploited category and number of blocks is under critical category. In view of the growing concerns of sustainability of ground water sources, immediate attention is required to augment groundwater resources in stressed areas. Irrigated agriculture in the state is putting additional stress on the groundwater system and needs proper management of the resources. Central Ground Water Board is providing all technical input for effective management of ground water resources in the state. The groundwater scenario compiled on administrative divisions gives a better perspective for planning various ground water management measures by local administrative bodies. With this objective, Central Ground Water Board is publishing the revised groundwater information booklet for all the districts of the state. I do appreciate the efforts of Dr. K.Md.Najeeb, Regional Director and his fleet of dedicated Scientists of South Western Region, Bangalore for bringing out this booklet. I am sure these brochures will provide a portrait of the groundwater resources in each district for planning effective management measures by the administrators, planners and the stake holders. Dr. S. C. Dhiman PREFACE Ground water contributes to about eighty percent of the drinking water requirements in the rural areas, fifty percent of the urban water requirements and more than fifty percent of the irrigation requirements of the nation. -

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile WESTERN GHATS & SRI LANKA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT WESTERN GHATS REGION FINAL VERSION MAY 2007 Prepared by: Kamal S. Bawa, Arundhati Das and Jagdish Krishnaswamy (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology & the Environment - ATREE) K. Ullas Karanth, N. Samba Kumar and Madhu Rao (Wildlife Conservation Society) in collaboration with: Praveen Bhargav, Wildlife First K.N. Ganeshaiah, University of Agricultural Sciences Srinivas V., Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning incorporating contributions from: Narayani Barve, ATREE Sham Davande, ATREE Balanchandra Hegde, Sahyadri Wildlife and Forest Conservation Trust N.M. Ishwar, Wildlife Institute of India Zafar-ul Islam, Indian Bird Conservation Network Niren Jain, Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation Jayant Kulkarni, Envirosearch S. Lele, Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment & Development M.D. Madhusudan, Nature Conservation Foundation Nandita Mahadev, University of Agricultural Sciences Kiran M.C., ATREE Prachi Mehta, Envirosearch Divya Mudappa, Nature Conservation Foundation Seema Purshothaman, ATREE Roopali Raghavan, ATREE T. R. Shankar Raman, Nature Conservation Foundation Sharmishta Sarkar, ATREE Mohammed Irfan Ullah, ATREE and with the technical support of: Conservation International-Center for Applied Biodiversity Science Assisted by the following experts and contributors: Rauf Ali Gladwin Joseph Uma Shaanker Rene Borges R. Kannan B. Siddharthan Jake Brunner Ajith Kumar C.S. Silori ii Milind Bunyan M.S.R. Murthy Mewa Singh Ravi Chellam Venkat Narayana H. Sudarshan B.A. Daniel T.S. Nayar R. Sukumar Ranjit Daniels Rohan Pethiyagoda R. Vasudeva Soubadra Devy Narendra Prasad K. Vasudevan P. Dharma Rajan M.K. Prasad Muthu Velautham P.S. Easa Asad Rahmani Arun Venkatraman Madhav Gadgil S.N. Rai Siddharth Yadav T. Ganesh Pratim Roy Santosh George P.S. -

Of the UGC Act 1956 (2014-15)

List of Colleges included Under 2(f) & 12(b) of the UGC Act 1956 (2014-15) Sl.No Name of the College Inclusion of college under Status of the College 2(f) 12(b) Government First Grade College, 01 Bapujinagar, Shimoga - 577 201. 2(f) 12(b) Government Acharya Tulsi National Commerce Affiliated 02 College, Mahaveer Circle, 2(f) 12(b) Balraj Urs Road, Shimoga-577 201. (Permanent) Sahyadri Arts & Commerce College, 03 Vidyanagar, 2(f) 12(b) Constituent Shimoga - 577 203. Sahyadri Science College, Constituent 04 Vidyanagar, 2(f) 12(b) Shimoga - 577 203. (Autonomous) D.V.S. Arts & Science College, Affiliated 05 Shimoga - 577 201. 2(f) 12(b) (Permanent) D.V.S. Evening College, Affiliated 06 Sri Basaveshwara Circle, 2(f) _ Sir M.V.Road, Shimoga-577 201. (Temporary) Kamala Nehru Memorial National Arts, Commerce & Science College 2(f) 12(b) Affiliated 07 for Women, Post Box No.66, (Permanent) K.T.Shamaiahgowda Road, Shimoga - 577 201. S.R.Nagappa Shetty Memorial 08 National College of Applied Sciences, Affiliated 2(f) 12(b) (Permanent) Balraj Urs Road, Shimoga - 577 201. Edurite College of Administration & Management Studies, First Floor, 2(f) _ 09 Affiliated Chikkanna Complex, Gandhinagar, (Temporary) Shimoga - 577 201. Sri Maruthi First Grade College, Affiliated 10 Holalur - 577 216, Shimoga District. _ 2(f) (Temporary) Government First Grade College, _ 11 Hosamane, Bhadravathi - 577 301. 2(f) Government Sir M.V.Government Science College, Bommanakatte, 12 2(f) 12(b) Affiliated Bhadravathi - 577 301, (Permanent) Shimoga District. ...2 -2- Sir M.V. Government College of Arts & Commerce, New Town, 2(f) 12(b) Government 13 Bhadravathi -577 301, (Permanent) Shimoga District. -

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 1 T B Dam DB NCL 3x2750 7.950 2 Bhadra LBC CB 2.000 3 Devraya CB 0.500 4 Gokak Fall ROR 2.500 5 Gokak Mills CB 1.500 6 Himpi CB CB 7.200 7 Iruppu fall ROR 5.000 8 Kattepura CB 5.000 9 Kattepura RBC CB 0.500 10 Narayanpur CB 1.200 11 Shri Ramadevaral CB 0.750 12 Subramanya CB 0.500 13 Bhadragiri Shimoga CB M/S Bhadragiri Power 4.500 14 Hemagiri MHS Mandya CB Trishul Power 1x4000 4.000 19.08.2005 15 Kalmala-Koppal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x400 0.400 1990 16 Sirwar Belagavi CB KPCL 1x1000 1.000 24.01.1990 17 Ganekal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x350 0.350 19.11.1993 18 Mallapur Belagavi DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 29.11.1992 19 Mani dam Raichur DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 24.12.1993 20 Bhadra RBC Shivamogga CB KPCL 1x6000 6.000 13.10.1997 21 Shivapur Koppal DB BPCL 2x9000 18.000 29.11.1992 22 Shahapur I Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1300 1.300 18.03.1997 23 Shahapur II Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1301 1.300 18.03.1997 24 Shahapur III Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1302 1.300 18.03.1997 25 Shahapur IV Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1303 1.300 18.03.1997 26 Dhupdal Belagavi CB Gokak 2x1400 2.800 04.05.1997 AHEC-IITR/SHP Data Base/July 2016 141 S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 27 Anwari Shivamogga CB Dandeli Steel 2x750 1.500 04.05.1997 28 Chunchankatte Mysore ROR Graphite India 2x9000 18.000 13.10.1997 Karnataka State 29 Elaneer ROR Council for Science and 1x200 0.200 01.01.2005 Technology 30 Attihalla Mandya CB Yuken 1x350 0.350 03.07.1998 31 Shiva Mandya CB Cauvery 1x3000 3.000 10.09.1998 -

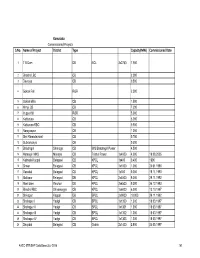

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

Final Project Completion Report

CEPF SMALL GRANT FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Organization Legal Name: Wildlife Information Liaison Development Society (WILDS) Promoting coordinated civil society action for biodiversity Project Title: conservation in the Malnad-Kodagu Corridor of the Western Ghats. Date of Report: 02-August-2015 Report Author and Contact Mr. Anup B Prakash Information CEPF Region: Western Ghats (Sahyadri-Konkan corridor) CEPF Strategic Direction: 1 Enable action by diverse communities and partnerships to ensure conservation of key biodiversity areas and enhance connectivity in the corridors. Grant Amount: $ 19,989.08 Project Dates: 1st September 2013 to 31st December 2014 Implementation Partners for this Project (please explain the level of involvement for each partner): 1. National Center for Biological Sciences, Bangalore – Technical support. Including providing review of proposal and feedback on planned activities – mainly on social surveys and GIS related work. 2. Agumbe rainforest research station, Agumbe – Logistical support including subsidized stay and vehicle from Apr 2014 to Oct 2014. Helped in identifying local people involved in various capacities in conservation related activities and conducted camps in conjunction with the project. Main project partner for the project in Shimoga district. 3. Agumbe Vikas Manch – a citizen’s collective in Agumbe provided manpower throughout the project and helped in organizing and setting up workshops for the forest department and villagers. 4. Poorna Pragna School, Udupi district – Dr. Ananthram Madhyastha for guidance on local contacts and feedback on activities 5. Malathi river protection front, Teerthahalli: Organized once-in-two month meetings between local activists in Teerthahalli taluk. 6. Kodachadri Jeep drivers’ association, Hosanagara Taluk: provided free-of-cost transport to local group during ground-truthing activity and also helped in setting up non-timber forest product co-operative in village forests in Hosanagara taluk 7. -

Bird Diversity of the Sharavathy Landscape, Karnataka Sahas Barve & Rekha Warrier

BARVE & WARRIER: Sharavathy landscape 57 Bird diversity of the Sharavathy landscape, Karnataka Sahas Barve & Rekha Warrier Barve, S., & Warrier, R., 2013. Bird diversity of the Sharavathy landscape, Karnataka. Indian BIRDS 8 (3): 57–61. Sahas Barve, A 503 Ascona, Raheja Gardens, Teen Haat Naka, LBS Marg, Thane- 400604, Maharashtra, India. Email: [email protected] Rekha Warrier, B-3/14, New Vivek.coop.hsg.soc, Shreenagar Estate, Goregaon (west), Mumbai 400062. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received on 4 April 2011. Abstract We present a description of the avifauna recorded during a survey of the Sharavathy area, central Western Ghats, Karnataka. The survey was carried out between November 2008 and March 2010. The major habitats available in the landscape are described along with a brief note on important bird records from the area. A total of 215 species were sighted during the survey of which 15 are endemic to the Western Ghats. Four ‘Near-threatened,’ and one ‘Vulnerable’ species, as per IUCN threat category, were recorded. A complete checklist of species recorded from the area is also given along with their respective relative abundance levels recorded during the survey. Introduction The Western Ghats are a “biodiversity hot spot” characterised by high diversity and endemicity (Myers et al. 2000). The altitudinal and rainfall gradients have created an array of habitat types all along the ghats, from dry deciduous forests in the north, to wet evergreen and stunted montane forests in the south. The geographically isolated evergreen forests of this region have many bird species in common with north-eastern India and the greater Oriental Region. -

Western Ghats

Western Ghats From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "Sahyadri" redirects here. For other uses, see Sahyadri (disambiguation). Western Ghats Sahyadri सहहदररद Western Ghats as seen from Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu Highest point Peak Anamudi (Eravikulam National Park) Elevation 2,695 m (8,842 ft) Coordinates 10°10′N 77°04′E Coordinates: 10°10′N 77°04′E Dimensions Length 1,600 km (990 mi) N–S Width 100 km (62 mi) E–W Area 160,000 km2 (62,000 sq mi) Geography The Western Ghats lie roughly parallel to the west coast of India Country India States List[show] Settlements List[show] Biome Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests Geology Period Cenozoic Type of rock Basalt and Laterite UNESCO World Heritage Site Official name: Natural Properties - Western Ghats (India) Type Natural Criteria ix, x Designated 2012 (36th session) Reference no. 1342 State Party India Region Indian subcontinent The Western Ghats are a mountain range that runs almost parallel to the western coast of the Indian peninsula, located entirely in India. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is one of the eight "hottest hotspots" of biological diversity in the world.[1][2] It is sometimes called the Great Escarpment of India.[3] The range runs north to south along the western edge of the Deccan Plateau, and separates the plateau from a narrow coastal plain, called Konkan, along the Arabian Sea. A total of thirty nine properties including national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserve forests were designated as world heritage sites - twenty in Kerala, ten in Karnataka, five in Tamil Nadu and four in Maharashtra.[4][5] The range starts near the border of Gujarat and Maharashtra, south of the Tapti river, and runs approximately 1,600 km (990 mi) through the states of Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu ending at Kanyakumari, at the southern tip of India. -

002 Adyanadka D.NO.492/2A, KEPU VILLAGE, ADYANADKA

Sl. Address No. SOL ID Branch Name Contact email id D.NO.492/2A, KEPU VILLAGE, 002 Adyanadka 9449595621 [email protected] 1 ADYANADKA Sri Krishna Upadhyaya Complex, 003 Airody 9449595625 [email protected] 2 NH66, Near Bus Stand, Sasthana Plot No. 1185, First Floor, Srinivas 005 Almel Nilaya, Indi Road, Near APMC, 9449595573 [email protected] 3 Almel TAPOVANA COMPLEX, SHIRAL 006 Anavatti KOPPA - HANGAL ROAD, 9449595401 [email protected] 4 ANAVATTI Ground Floor, Bharath Complex, 007 Arehalli 9449595402 [email protected] 5 Belur Road, Arehalli 6 009 Arsikere-Main LAKSHMI, B.H.ROAD, ARSIKERE 9449595404 [email protected] “Ganesh Ram Arcade”, No.213, B 010 Ayanur 9449595520 [email protected] 7 H Road, Ayanur Ist FLOOR, LOURDES COMPLEX, 011 Amtady AMTADY, LORETTO POST, 9449595624 [email protected] 8 AMTADY, BANTWAL TALUK. RAMAKRISHNA NILAYA, POST 012 Aikala 9449595622 [email protected] 9 KINNIGOLI, AIKALA Door No. 1/89(11), SY. No. 78/12, Old SY No. 78/4P2, “Sinchana Complex”, Ground Floor, 013 Amasebail 9449595626 [email protected] Amasebail Siddapura Road, Amasebail Village, Kundapura 10 Taluk, Udupi District – 576227 OPP.PUSHPANJALI TALKIES, 014 Agali 8500801827 [email protected] 11 MADAKASIRA ROAD, AGALI. GROUND FLOOR, NO.47/1, SRI 015 Aladangady LAXMI NILAYA, MAIN ROAD, ANE 9449595623 [email protected] 12 MAHAL, ALADANGADY Ist FLOOR, DURGA Udupi-Adi 016 INTERNATIONAL BUILDING, 9449595595 [email protected] Udupi 13 UDUPI-MALPE ROAD, UDUPI BUILDING1(817), OPP.HOTEL Goa-Alto 017 O'COQUEIRO, PANAJI-MAPUSA 9423057235 [email protected] Porvorim 14 HIGH WAY, ALTO PORVORIM SUJATHA COMPLEX, MANIPAL Udupi- 018 CROSS ROAD, AMBAGILU- 9448463283 [email protected] Ambagilu 15 UDUPI CTS No.