Potentially Vulnerable Species: Animals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surveys for Dun Skipper (Euphyes Vestris) in the Harrison Lake Area, British Columbia, July 2009

Surveys for Dun Skipper (Euphyes vestris) in the Harrison Lake Area, British Columbia, July 2009 Report Citation: Parkinson, L., S.A. Blanchette, J. Heron. 2009. Surveys for Dun Skipper (Euphyes vestris) in the Harrison Lake Area, British Columbia, July 2009. B.C. Ministry of Environment, Ecosystems Branch, Wildlife Science Section, Vancouver, B.C. 51 pp. Cover illustration: Euphyes vestris, taken 2007, lower Fraser Valley, photo by Denis Knopp. Photographs may be used without permission for non-monetary and educational purposes, with credit to this report and photographer as the source. The cover photograph is credited to Denis Knopp. Contact Information for report: Jennifer Heron, Invertebrate Specialist, B.C. Ministry of Environment, Ecosystems Branch, Wildlife Science Section, 316 – 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, V6T 1Z1. Phone: 604-222-6759. Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements Fieldwork was conducted by Laura Parkinson and Sophie-Anne Blanchette, B.C. Conservation Corps Invertebrate Species at Risk Crew. Jennifer Heron (B.C. Ministry of Environment) provided maps, planning and guidance for this project. The B.C. Invertebrate Species at Risk Inventory project was administered by the British Columbia Conservation Foundation (Joanne Neilson). Funding was provided by the B.C. Ministry of Environment through the B.C. Conservation Corp program (Ben Finkelstein, Manager and Bianka Sawicz, Program Coordinator), the B.C. Ministry of Environment Wildlife Science Section (Alec Dale, Manager) and Conservation Framework Funding (James Quayle, Manager). Joanne Neilson (B.C. Conservation Foundation) was a tremendous support to this project. This project links with concurrent invertebrate stewardship projects funded by the federal Habitat Stewardship Program for species at risk. -

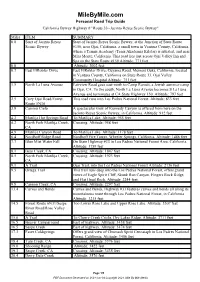

Campground East of Highway

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide California Byway Highway # "Route 33--Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Start of Jacinto Reyes Start of Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, at the Junction of State Route Scenic Byway #150, near Ojai, California, a small town in Ventura County, California, where a Tennis Academy (Tenis Akademia Kilatas) is situated, and near Mira Monte, California. This road lies just across Ojai Valley Inn and Spa on the State Route #150 Altitude: 771 feet 0.0 Altitude: 3002 feet 0.7 East ElRoblar Drive East ElRoblar Drive, Cuyama Road, Meiners Oaks, California, located in Ventura County, California on State Route 33, Ojai Valley Community Hospital Altitude: 751 feet 1.5 North La Luna Avenue Fairview Road goes east-north to Camp Ramah, a Jewish summer camp in Ojai, CA. To the south, North La Luna Avenue becomes S La Luna Avenue and terminates at CA State Highway 150. Altitude: 797 feet 2.5 Cozy Ojai Road/Forest This road runs into Los Padres National Forest. Altitude: 833 feet Route 5N34 3.9 Camino Cielo A spectacular view of Kennedy Canyon is offered from here on the Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, in California. Altitude: 912 feet 4.2 Matilija Hot Springs Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 955 feet 4.2 North Fork Matilija Creek, Crossing. Altitude: 958 feet CA 4.9 Matilija Canyon Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 1178 feet 6.4 Nordhoff Ridge Road Nordhoff Fire Tower, Wheeler Springs, California. Altitude: 1486 feet 7.7 Blue Mist Water Fall On State Highway #33 in Los Padres National Forest Area, California. -

Richard F. Ambrose

CURRICULUM VITAE RICHARD F. AMBROSE Department of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health Institute of the Environment and Sustainability (310) 825-6144 University of California FAX (310) 794-2106 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. 1982 University of California, Los Angeles. B.S. 1975 University of California, Irvine. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2000-present Professor Department of Environmental Health Sciences Institute of the Environment and Sustainability (joint appointment 2008-present) University of California, Los Angeles 1998-2011 Director Environmental Science and Engineering Program, UCLA 1992-2000 Associate Professor Department of Environmental Health Sciences, UCLA 1985-1997 Assistant (1985-1991) and Associate (1991-97) Research Biologist Marine Science Institute University of California, Santa Barbara 1983-1984 Postdoctoral Fellow Department of Biological Sciences Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C., Canada V5A 1S6 1982 Visiting Lecturer Department of Biology, UCLA RESEARCH Major Research Interests Restoration ecology, especially for coastal marine and estuarine environments Relationship between ecosystem health and human health Urban ecology, including ecological aspects of sustainable water management Coastal ecology, including ecology of coastal wetlands and estuaries Interface between environmental biology and resource management policy Richard F. Ambrose - page 2 Research Grants and Contracts, R.F. Ambrose - Principal Investigator Marine Review Committee, Inc. A study of mitigation -

Tijuana River Valley Existing Conditions Report

Climate Understanding & Resilience in the River Valley Tijuana River Valley Existing Conditions Report Prepared by the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve for the CURRV project’s Stakeholder Working Group Updated April 14, 2014 This project is funded by a grant from the Coastal and Ocean Climate Applications Program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Program Office. Also, supported in part by a grant from the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS) Science Collaborative. 1 Table of Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Figures ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Resources and Geography ........................................................................................................................... 6 Climate ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Topography & Floodplain ....................................................................................................................... 6 Hydrology .............................................................................................................................................. -

Philmont Butterflies

PHILMONT AREA BUTTERFLIES Mexican Yellow (Eurema mexicana) Melissa Blue (Lycaeides melissa) Sleepy Orange (Eurema nicippe) Greenish Blue (Plebejus saepiolus) PAPILIONIDAE – Swallowtails Dainty Sulfur (Nathalis iole) Boisduval’s Blue (Icaricia icarioides) Subfamily Parnassiinae – Parnassians Lupine Blue (Icaricia lupini) Rocky Mountain Parnassian (Parnassius LYCAENIDAE – Gossamer-wings smintheus) Subfamily Lycaeninae – Coppers RIODINIDAE – Metalmarks Tailed Copper (Lycaena arota) Mormon Metalmark (Apodemia morma) Subfamily Papilioninae – Swallowtails American Copper (Lycaena phlaeas) Nais Metalmark (Apodemia nais) Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) Lustrous Copper (Lycaena cupreus) Old World Swallowtail (Papilio machaon) Bronze Copper (Lycaena hyllus) NYMPHALIDAE – Brush-footed Butterflies Anise Swallowtail (Papilio zelicaon) Ruddy Copper (Lycaena rubidus) Subfamily Libytheinae – Snout Butterflies Western Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio rutulus) Blue Copper (Lycaena heteronea) American Snout (Libytheana carinenta) Pale Swallowtail (Papilio eurymedon) Purplish Copper (Lycaena helloides) Two-tailed Swallowtail (Papilio multicaudatus) Subfamily Heliconiinae – Long-wings Subfamily Theclinae – Hairstreaks Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) PIERIDAE – Whites & Sulfurs Colorado Hairstreak (Hypaurotis crysalus) Subfamily Pierinae – Whites Great Purple Hairstreak (Atlides halesus) Subfamily Argynninae – Fritillaries Pine White (Neophasia menapia) Southern Hairstreak (Fixsenia favonius) Variegated Fritillary (Euptoieta claudia) Becker’s White (Pontia -

Biological Conservation 228 (2018) 310–318

Biological Conservation 228 (2018) 310–318 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Multi-scale effects of land cover and urbanization on the habitat suitability of an endangered toad T ⁎ Michael L. Tregliaa, , Adam C. Landonb,c,1, Robert N. Fisherd, Gerard Kyleb, Lee A. Fitzgeralda a Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections, Applied Biodiversity Science Program, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2258, USA b Human Dimensions of Natural Resources Lab, Department of Recreation, Parks, and Tourism Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2261, USA c Water Management and Hydrological Science Program, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-3408, USA d U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, San Diego Field Station, San Diego, CA, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Habitat degradation, entwined with land cover change, is a major driver of biodiversity loss. Effects of land cover Watersheds change on species can be direct (when habitat is converted to alternative land cover types) or indirect (when Structural equation model land outside of the species habitat is altered). Hydrologic and ecological connections between terrestrial and California aquatic systems are well understood, exemplifying how spatially disparate land cover conditions may influence Arroyo toad aquatic habitats, but are rarely examined. We sought to quantify relative effects of land cover at two different but Anaxyrus californicus interacting scales on habitat suitability for the endangered arroyo toad (Anaxyrus californicus). Based on an Anthropogenic development ff Riparian areas existing distribution model for the arroyo toad and available land cover data, we estimated e ects of land cover along streams and within entire watersheds on habitat suitability using structural equation modeling. -

Description of Source Water System

CHAPTER 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE SOURCE WATER SYSTEM 2.0 Description of the Source Water System During the last 100 years, the CSD’s water system has evolved into a very complex system. It is now estimated to serve a population of 1.4 million people spread out over 370 square miles (Table 2.1). The CSD treats imported raw water and local runoff water at three City WTPs which have a combined capacity of 378 MGD. The CSD treats water by conventional technologies using coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation, filtration and disinfection. Recently, all CSD water treatment plants have been modified to provide for the addition of fluoride to the potable water supply. To ensure safe and palatable water quality, the CSD collects water samples at its reservoirs, WTPs, and throughout the treated water storage and distribution system. The CSD’s use of local and imported water to meet water demand is affected by availability, cost, and water resource management policies. Imported water availability decreases the need to carry over local water for dry years in City reservoirs. CSD policy is to use local water first to reduce imported water purchases; this policy runs the risk of increased dependence on imported water during local droughts. Table 2.1 - City of San Diego General Statistics Population (2010) 1,301,621 Population (Estimated 2014) 1,381,069 Population percent change 6.1 Land Area Square Miles 370 Population Density per Square Mile 3733 Water Distribution Area Square Miles 403 Number of Service Connections (2015) 279,102 2.1 Water Sources (Figure 2.1) Most of California's water development has been dictated by the multi-year wet/dry weather cycles. -

Section 5 References

Section 5 References 5.0 REFERENCES Akçakaya, H. R. and J. L. Atwood. 1997. A habitat-based metapopulation model of the California Gnatcatcher. Conservation Biology 11:422-434. Akçakaya, H.R. 1998. RAMAS GIS: Linking landscape data with population viability analysis (version 3.0). Applied Biomathematics, Setaauket, New York. Anderson, D.W. and J.W. Hickey. 1970. Eggshell changes in certain North American birds. Ed. K. H. Voous. Proc. (XVth) Inter. Ornith. Congress, pp 514-540. E.J. Brill, Leiden, Netherlands. Anderson, D.W., J.R. Jehl, Jr., R.W. Risebrough, L.A. Woods, Jr., L.R. Deweese, and W.G. Edgecomb. 1975. Brown pelicans: improved reproduction of the southern California coast. Science 190:806-808. Atwood, J.L. 1980. The United States distribution of the California black-tailed gnatcatcher. Western Birds 11: 65-78. Atwood, J.L. 1990. Status review of the California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica). Unpublished Technical Report, Manomet Bird Observatory, Manomet, Massachusetts. Atwood, J.L. 1992. A maximum estimate of the California gnatcatcher’s population size in the United States. Western Birds. 23:1-9. Atwood, J.L. and J.S. Bolsinger. 1992. Elevational distribution of California gnatcatchers in the United States. Journal of Field Ornithology 63:159-168. Atwood, J.L., S.H. Tsai, C.H. Reynolds, M.R. Fugagli. 1998. Factors affecting estimates of California gnatcatcher territory size. Western Birds 29: 269-279. Baharav, D. 1975. Movement of the horned lizard Phrynosoma solare. Copeia 1975: 649-657. Barry, W.J. 1988. Management of sensitive plants in California state parks. Fremontia 16(2):16-20. Beauchamp, R.M. -

Arroyo Toad (Anaxyrus Californicus) Life History, Population Status, Population

Arroyo Toad (Anaxyrus californicus) Life History, Population Status, Population Threats, and Habitat Assessment of Conditions at Fort Hunter Liggett, Monterey County, California A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biology by Jacquelyn Petrasich Hancock December 2009 © 2009 Jacquelyn Petrasich Hancock ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Arroyo Toad (Anaxyrus californicus) Life History, Population Status, Population Threats, and Habitat Assessment of Conditions at Fort Hunter Liggett, Monterey County, California AUTHOR: Jacquelyn Petrasich Hancock DATE SUBMITTED: December 2009 COMMITTEE CHAIR: David Pilliod, PhD COMMITTEE MEMBER: Emily Taylor, PhD COMMITTEE MEMBER: Scott Steinmaus, PhD iii Abstract Arroyo Toad (Anaxyrus californicus) Life History, Population Status, Population Threats, and Habitat Assessment of Conditions at Fort Hunter Liggett, Monterey County, California Jacquelyn Petrasich Hancock The arroyo toad (Anaxyrus californicus) is a federally endangered species found on Fort Hunter Liggett, Monterey County, California. The species was discovered in 1996 and was determined to occupy 26.7 km of the San Antonio River from approximately 2.4 km northwest of the San Antonio Mission de Padua, to the river delta above the San Antonio Reservoir. The construction of the San Antonio Reservoir dam in 1963 isolated this northern population of arroyo toads. Through time, the Fort Hunter Liggett landscape has changed drastically. The land was heavily grazed by cattle until 1991, which considerably reduced vegetation in riparian areas. Military training following acquisition of the land in 1940 far exceeded current allowable training. Fire was used extensively to reduce unfavorable vegetation, and as a result, extreme tree loss occurred through the ranges. -

Idyllwild $31,220 Tuesday, Aug

Summer Concer llwild t Seri 75¢ Idy Your es (Tax Included) Needs Help! Total needed $32,420 As of Idyllwild $31,220 Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2016 Idyllwild’s Only Newspaper Send Donations to: Idyllwild Tow n Crıer Summer Concerts Inc. P.O. Box ALMOST ALL THE NEWS — PART OF THE TIME ... ONLINE ALL THE TIME AT IDYLLWILDTOWNCRIER.COM 1542, Idyllwild, CA 92549-1542 VOL. 71 NO. 35 IDYLLWILD, CA THURS., SEPTEMBER 1, 2016 Labor Day Yard Sale Local students’ Treasure Map, pg. 18 performance NEWS on state tests: Horse trapped in ravine rescued after excellent and two days, page 2 improving Idyllwild Brewpub BY JP CRUMRINE plans ‘green’ NEWS EDITOR operations, pg. 6 Last week, the California Department of Education released the results of the second California Assessment Cal Fire, Riverside County Fire Department, the U.S. Forest Ser- of Student Performance and Progress, and once again, IFPD parcel measure vice, the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department and members of the Idyllwild School’s performance was better than state- on November ballot, Horse & Animal Rescue Team coordinated the rescue and recovery of a Forest Service volunteer’s horse who slid down a steep ravine wide or districtwide averages. page 7 in the Apple Canyon area. The horse is shown above, still sedated “We did well, scoring higher than Riverside County after it was airlifted (see inset photo, left). Read more on page 2. [students] in every grade level,” said Idyllwild School PHOTOS COURTESY RIVERSIDE COUNTY ANIMAL SERVICES Principal Matt Kraemer. “And we were above Hemet On The Town district average.” At Idyllwild, grades three through eight were tested. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Euphyes Scudder (Hesperiidae)

JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY Volume 47 1993 Number 4 Journal of the Lepidopterists Society 47(4), 1993, 261-278 PHYLOGENY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF EUPHYES SCUDDER (HESPERIIDAE) JOHN A. SHUEyl Great Lakes Environmental Center, 739 Hastings, Traverse City, Michigan 49684 ABSTRACT. The 20 species of Euphyes were analyzed phylogenetically and were found to fall into four monophyletic species groups, each of which is defined by one or more apomorphic characters. The peneia group contains Euphyes peneia (Godman), E. eberti Mielke, E. leptosema (Mabille), E. fumata Mielke, E. singularis (Herrich-Schiiffer), and E. cornelius (Latreille). The subferruginea group contains E. subferruginea Mielke, E. antra Evans, and E. cherra Evans. The dion group contains E. dion (Edwards), E. dukesi (Lindsey), E. bayensis Shuey, E. pilatka (Edwards), E. berryi (Bell), and E. con spicua (Edwards). The vestris group contains E. vestris (Boisduval), E. chamuli Freeman, E. bimacula (Grote and Robinson), and E arpa (Boisduval and Leconte). Euphyes ampa Evans could not be placed confidently w .nin this framework. Geographic distribution of each speci~s group suggests that exchange between South America and North America took place at least twice. The two Caribbean Basin species (E. singularis, E. cornelius) share a common ancestor with E. peneia, a species found in Central and South America. This suggests a vicariant event involving Central America and the Greater Antilles. The dion and vestris groups show strong patterns of alJopatric differentiation, suggesting that the isolation and subsequent differentiation of peripheral populations has played an important role in the development of the extant species. Additional key words: evolution, cladistics, wetlands, vicariance biogeography, pop ulation differentiation. -

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Macroparasite Study of Cypriniform fishes in the Santa Clara Drainage Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3kp0q16j Author Murray, Max DeLonais Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Macroparasite Study of Cypriniform fishes in the Santa Clara Drainage A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Biology by Max DeLonais Murray 2019 © Copyrite by Max DeLonais Murray 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Macroparasite Study of Cypriniform fishes in the Santa Clara Drainage by Max DeLonais Murray Master of Science in Biology University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Donald G. Buth, Chair Several species of fishes have been introduced into the Santa Clara River system in southern California, including Catostomus santaanae (Santa Ana sucker), Catostomus fumeiventris (Owens sucker), Gila orcutti (arroyo chub), and Pimephales promelas (fathead minnow). These species are known to inhabit similar ecological niches but little is known about their associated parasite fauna. Two C. fumeiventris, 35 C. santaanae, 63 hybrid catostomids, 214 G. orcutti, and 18 P. promelas were collected and necropsied in the summers of 2017 and 2018. Nine macroparasite taxa were harvested including seven native, and two nonnative parasites Schyzocotyle acheilognathi (Asian fish tapeworm) and Lernaea cyprinacea (anchor worm). Prevalence and intensity of parasites were not related to the genetic history of these catostomids. This is the first host-association record for G. orcutti with Gyrodactylus sp., S. acheilognathi, ii diplostomid metacercariae, Rhabdochona sp, Contracaecum sp., and larval acuariid cysts and for P.