Canada Negotiations 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C. Dewar Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes, Volume 53, Number/numéro 1, Winter/hiver 2019, pp. 178-196 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719555 Access provided by Mount Saint Vincent University (19 Mar 2019 13:29 GMT) Journal of Canadian Studies • Revue d’études canadiennes Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent KENNETH C. DEWAR Abstract: This article argues that the lines separating different modes of thought on the centre-left of the political spectrum—liberalism, social democracy, and socialism, broadly speaking—are permeable, and that they share many features in common. The example of Tom Kent illustrates the argument. A leading adviser to Lester B. Pearson and the Liberal Party from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Kent argued for expanding social security in a way that had a number of affinities with social democracy. In his paper for the Study Conference on National Problems in 1960, where he set out his philosophy of social security, and in his actions as an adviser to the Pearson government, he supported social assis- tance, universal contributory pensions, and national, comprehensive medical insurance. In close asso- ciation with his philosophy, he also believed that political parties were instruments of policy-making. Keywords: political ideas, Canada, twentieth century, liberalism, social democracy Résumé : Cet article soutient que les lignes séparant les différents modes de pensée du centre gauche de l’éventail politique — libéralisme, social-démocratie et socialisme, généralement parlant — sont perméables et qu’ils partagent de nombreuses caractéristiques. -

Hill Times, Health Policy Review, 17NOV2014

TWENTY-FIFTH YEAR, NO. 1260 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2014 $4.00 HEARD ON THE HILL BUZZ NEWS HARASSMENT Artist paints Queen, other prominent MPs like ‘kings, queens in their people, wants a national portrait gallery little domains,’ contribute to ‘culture of silence’: Clancy BY LAURA RYCKEWAERT “The combination of power and testosterone often leads, unfortu- n arm’s-length process needs nately, to poor judgment, especially Ato be established to deal in a system where there has been with allegations of misconduct no real process to date,” said Nancy or harassment—sexual and Peckford, executive director of otherwise—on Parliament Hill, Equal Voice Canada, a multi-par- say experts, as the culture on tisan organization focused on the Hill is more conducive to getting more women elected. inappropriate behaviour than the average workplace. Continued on page 14 NEWS HARASSMENT Campbell, Proctor call on two unnamed NDP harassment victims to speak up publicly BY ABBAS RANA Liberal Senator and a former A NDP MP say the two un- identifi ed NDP MPs who have You don’t say: Queen Elizabeth, oil on canvas, by artist Lorena Ziraldo. Ms. Ziraldo said she got fed up that Ottawa doesn’t have accused two now-suspended a national portrait gallery, so started her own, kind of, or at least until Nov. 22. Read HOH p. 2. Photograph courtesy of Lorena Ziraldo Liberal MPs of “serious person- al misconduct” should identify themselves publicly and share their experiences with Canadians, NEWS LEGISLATION arguing that it is not only a ques- tion of fairness, but would also be returns on Monday, as the race helpful to address the issue in a Feds to push ahead on begins to move bills through the transparent fashion. -

The NDP's Approach to Constitutional Issues Has Not Been Electorally

Constitutional Confusion on the Left: The NDP’s Position in Canada’s Constitutional Debates Murray Cooke [email protected] First Draft: Please do not cite without permission. Comments welcome. Paper prepared for the Annual Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association, June 2004, Winnipeg The federal New Democratic Party experienced a dramatic electoral decline in the 1990s from which it has not yet recovered. Along with difficulties managing provincial economies, the NDP was wounded by Canada’s constitutional debates. The NDP has historically struggled to present a distinctive social democratic approach to Canada’s constitution. Like its forerunner, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the NDP has supported a liberal, (English-Canadian) nation-building approach that fits comfortably within the mainstream of Canadian political thought. At the same time, the party has prioritized economic and social polices rather than seriously addressing issues such as the deepening of democracy or the recognition of national or regional identities. Travelling without a roadmap, the constitutional debates of the 80s and 90s proved to be a veritable minefield for the NDP. Through three rounds of mega- constitutional debate (1980-82, 1987-1990, 1991-1992), the federal party leadership supported the constitutional priorities of the federal government of the day, only to be torn by disagreements from within. This paper will argue that the NDP’s division, lack of direction and confusion over constitution issues can be traced back to longstanding weaknesses in the party’s social democratic theory and strategy. First of all, the CCF- NDP embraced rather than challenged the parameters and institutions of liberal democracy. -

Vellacott V Saskatoon Starphoenix Group Inc. 2012 SKQB

QUEEN'S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN Citation: 2012 SKQB 359 Date: 2012 08 31 Docket: Q.B.G. No. 1725 I 2002 Judicial Centre: Saskatoon IN THE COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN JUDICIAL CENTRE OF SASKATOON BETWEEN: MAURICE VELLACOTT, Plaintiff -and- SASKATOON STARPHOENIX GROUP INC., DARREN BERNHARDT and JAMES PARKER, Defendants Counsel: Daniel N. Tangjerd for the plaintiff Sean M. Sinclair for the defendants JUDGMENT DANYLIUKJ. August 31,2012 Introduction [1] The cut-and-thrust of politics can be a tough, even vicious, business. Not for the faint of heart, modem politics often means a participant's actions are examined - 2 - under a very public microscope, the lenses of which are frequently controlled by the media. While the media has obligations to act responsibly, there is no corresponding legal duty to soothe bruised feelings. [2] The plaintiff seeks damages based on his allegation that the defendants defamed him in two newspaper articles published in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix newspaper on March 4 and 5, 2002. The defendants state the words complained of were not defamatory and, even if they were, that they have defences to the claim. [3] To better organize this judgment, I have divided it into the following sections: Para~raphs Facts 4-45 Issues 46 Analysis 47- 115 1. Are the words complained of defamatory? 47-73 2. Does the defence of responsible journalism avail the defendants? 74-83 3. Does the defence of qualified privilege avail the defendants? 84-94 4. Does the defence of fair comment avail the defendants? 95- 112 5. Does the defence of consent avail the defendants? 113 6. -

Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy

Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy Annual Report 2019–20 2 munk school of global affairs & public policy About the Munk School Table of Contents About the Munk School ...................................... 2 Student Programs ..............................................12 Research & Ideas ................................................36 Public Engagement ............................................72 Supporting Excellence ......................................88 Faculty and Academic Directors .......................96 Named Chairs and Professorships....................98 Munk School Fellows .........................................99 Donors ...............................................................101 1 munk school of global affairs & public policy AboutAbout the theMunk Munk School School About the Munk School The Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy is a leader in interdisciplinary research, teaching and public engagement. Established in 2010 through a landmark gift by Peter and Melanie Munk, the School is home to more than 50 centres, labs and teaching programs, including the Asian Institute; Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies; Centre for the Study of the United States; Centre for the Study of Global Japan; Trudeau Centre for Peace, Conflict and Justice and the Citizen Lab. With more than 230 affiliated faculty and more than 1,200 students in our teaching programs — including the professional Master of Global Affairs and Master of Public Policy degrees — the Munk School is known for world-class faculty, research leadership and as a hub for dialogue and debate. Visit munkschool.utoronto.ca to learn more. 2 munk school of global affairs & public policy About the Munk School About the Munk School 3 munk school of global affairs & public policy 2019–20 annual report 3 About the Munk School Our Founding Donors In 2010, Peter and Melanie Munk made a landmark gift to the University of Toronto that established the (then) Munk School of Global Affairs. -

Annual Report (August 23, 2019 / 12:00:07) 114887-1 Munkschool-2018-19Annualreport.Pdf .2

(August 23, 2019 / 12:00:06) 114887-1_MunkSchool-2018-19AnnualReport.pdf .1 Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy 2018–19 Annual Report (August 23, 2019 / 12:00:07) 114887-1_MunkSchool-2018-19AnnualReport.pdf .2 The Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy The Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy at the University of Toronto is a leader in interdisciplinary research, teaching and public engagement. Established as a school in 2010 through a landmark gift by Peter and Melanie Munk, the Munk School is now home to 58 centres, labs and programs, including the Asian Institute; Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies; Centre for the Study of the United States; Trudeau Centre for Peace, Conflict and Justice and the Citizen Lab. With more than 230 affiliated faculty and nearly 1,200 students in our teaching programs, including the Master of Global Affairs and Master of Public Policy degrees, the Munk School is known in Canada and internationally for its research leadership, exceptional teaching programs and as a space for dialogue and debate. Visit munkschool.utoronto.ca to learn more. (August 23, 2019 / 12:00:07) 114887-1_MunkSchool-2018-19AnnualReport.pdf .3 Education in Action A place where students and teachers come together to understand and address some of the world’s most complex challenges. Where classrooms extend from our University of Toronto campus around the globe. Research Leadership Attracting top scholars. Examining challenging problems and promising opportunities. Bridging disciplines and building global networks. Public Engagement An essential space for discussion and debate. We invite scholars, practitioners, public figures and the wider community to join us in discussing today’s challenges and tomorrow’s solutions. -

Queen's Bench for Saskatchewan

QUEEN’S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN Citation: 2012 SKQB 359 Date: 20120831 Docket: Q.B.G.No. 1725/2002 Judicial Centre: Saskatoon IN THE COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN JUDICIAL CENTRE OF SASKATOON BETWEEN: MAURICE VELLACOTT, Plaintiff - and - SASKATOON STARPHOENIX GROUP INC., DARREN BERNFIARDT and JAMES PARKER, Defendants Counsel: Daniel N. Tangjerd for the plaintiff Sean M. Sinclair for the defendants JUDGMENT DANYLIUK J. August 31, 2012 Introduction [1] The cut-and-thrust of politics can be a tough, even vicious, business. Not for the faint of heart, modern politics often means a participant’s actions are examined -2- under a very public microscope, the lenses of which are frequently controlled by the media. While the media has obligations to act responsibly, there is no corresponding legal duty to soothe bruised feelings. [2] The plaintiff seeks damages based on his allegation that the defendants defamed him in two newspaper articles published in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix newspaper on March 4 and 5,2002. The defendants state the words complained of were not defamatory and, even if they were, that they have defences to the claim. [3] To better organize this judgment, I have divided it into the following sections: [tern Paragraphs Facts 4 - 45 Issues 46 Analysis 47 - 115 1. Are the words complained of defamatory? 47 - 73 2. Does the defence of responsible journalism avail the defendants? 74 - 83 3. Does the defence of qualified privilege avail the defendants? 84 - 94 4. Does the defence of fair comment avail the defendants? 95- 112 5. Does the defence of consent avail the defendants? 113 6. -

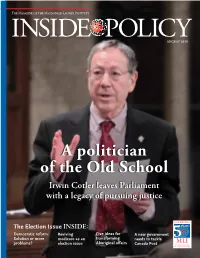

The August 2015 Issue of Inside Policy

AUGUST 2015 A politician of the Old School Irwin Cotler leaves Parliament with a legacy of pursuing justice The Election Issue INSIDE: Democratic reform: Reviving Five ideas for A new government Solution or more medicare as an transforming needs to tackle problems? election issue Aboriginal affairs Canada Post PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley, byCrowley, the Managing Macdonald-LaurierManaging Director,Director, [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames Anderson,Managing Anderson, Editor ManagingManaging and Editor, Editor,Communications Inside Inside Policy Policy Director Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:writers: Editor, Inside Policy Past contributors ThomasThomas S. AxworthyS. Axworthy ContributingAndrewAndrew Griffith writers: BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. AxworthyDonald Barry Laura Dawson Stanley H. HarttCarin Holroyd Mike Priaro Peggy Nash DonaldThomas Barry S. Axworthy StanleyAndrew H. GriffithHartt BenjaminMike PriaroPerrin Mary-Jane Bennett Elaine Depow Dean Karalekas Linda Nazareth KenDonald Coates Barry PaulStanley Kennedy H. Hartt ColinMike Robertson Priaro Carolyn BennettKen Coates Jeremy Depow Paul KennedyPaul Kennedy Colin RobertsonGeoff Norquay Massimo Bergamini Peter DeVries Tasha Kheiriddin Benjamin Perrin Brian KenLee Crowley Coates AudreyPaul LaporteKennedy RogerColin Robinson Robertson Ken BoessenkoolBrian Lee Crowley Brian -

Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA THE FUTURE ROLE OF THE GOVERNMENT IN AGRICULTURE Report of the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food Charles Hubbard, M.P. Chair June 2002 The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Evidence of Committee public meetings is available on the Internet http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Public Works and Government Services Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 THE FUTURE ROLE OF THE GOVERNMENT IN AGRICULTURE Report of the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food Charles Hubbard, M.P. Chair June 2002 STANDING COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE AND AGRI-FOOD CHAIR Charles Hubbard, M.P. Miramichi, New Brunswick VICE-CHAIRS Murray Calder, M.P. Dufferin—Peel—Wellington—Grey, Ontario Howard Hilstrom, M.P. Selkirk—Interlake, Manitoba MEMBERS David L. Anderson, M.P. Cypress Hills—Grasslands, Saskatchewan Rick Borotsik, M.P. Brandon—Souris, Manitoba Garry Breitkreuz, M.P. Yorkton—Melville, Saskatchewan Claude Duplain, M.P. Portneuf, Quebec Mark Eyking, M.P. Sydney—Victoria, Nova Scotia Marcel Gagnon, M.P. Champlain, Quebec Rick Laliberte, M.P. Churchill River, Saskatchewan Larry McCormick, M.P. -

Registration of Pesticides and the Competitiveness of Canadian Farmers

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA REGISTRATION OF PESTICIDES AND THE COMPETITIVENESS OF CANADIAN FARMERS Report of the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food Charles Hubbard, M.P. Chair May 2002 The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Public Works and Government Services Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 REGISTRATION OF PESTICIDES AND THE COMPETITIVENESS OF CANADIAN FARMERS Report of the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food Charles Hubbard, M.P. Chair May 2002 STANDING COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE AND AGRI-FOOD CHAIR Charles Hubbard, M.P. Miramichi, New Brunswick VICE-CHAIRS Murray Calder, M.P. Dufferin-Peel-Wellington-Grey, Ontario Howard Hilstrom, M.P. Selkirk—Interlake, Manitoba MEMBERS David L. Anderson, M.P. Cypress Hills—Grasslands, Saskatchewan Rick Borotsik, M.P. Brandon—Souris, Manitoba Garry Breitkreuz, M.P. Yorkton—Melville, Saskatchewan Claude Duplain, M.P. Portneuf, Quebec Mark Eyking, M.P. Sydney—Victoria, Nova Scotia Marcel Gagnon, M.P. Champlain, Quebec Rick Laliberte, M.P. Churchill River, Saskatchewan Larry McCormick, M.P. Hastings—Frontenac—Lennox and Addington, Ontario Dick Proctor, M.P. -

CBC Nir May 12.Indd

THE NDP CHOOSES A NEW LEADER Introduction On March 24, 2012, the members of the only in 2007 that he joined the NDP, Focus federal New Democratic Party chose recruited specifically by Jack Layton to This News in Review story examines the Thomas Mulcair as their new leader. be his Quebec lieutenant. rise of Thomas Mulcair Mulcair took control at an extraordinary Mulcair served Layton well, winning a to the leadership of time. It was less than one year since the seat in a 2007 by-election and becoming the New Democratic NDP had celebrated its best-ever election the architect of the NDP’s 59-seat victory Party (NDP) and how results, winning 102 seats and assuming in Quebec in the 2011 federal election. the NDP is changing the role of Official Opposition. And it In his campaign, Mulcair called for the under Mulcair. We also was only eight months after the death of party to modernize its language and consider the possibility that the rise of the Jack Layton, the NDP’s beloved leader approach to voters. His essential message NDP might result who had led the party to that historic was that the party could not win power in a new political election victory. without changing the way it campaigned. dynamic in the The leadership race was a contest “We did get 4.5 million votes but we ongoing competition between two factions within the NDP: are still far from being able to form a between progressives representatives of the party’s old guard, government,” he argued. -

Canadian Pain Society Conference May 23 – 26, 2007, Ottawa, Ontario

CPS_Abstracts_2007.qxd 27/04/2007 11:43 AM Page 107 ABSTRACTS Canadian Pain Society Conference May 23 – 26, 2007, Ottawa, Ontario COMMUNITY PUBLIC EVENT 8:45 AM – SESSION 101 WEDNESDAY MAY 23, 2007 3 THE NATURE AND NURTURE OF PAIN 6:30 PM – PAIN RELIEF – A BASIC HUMAN RIGHT UNDERSTANDING THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND THE 7:15 PM – PAIN MANAGEMENT AND REGULATORS IMPORTANCE OF GENETICS AND ENVIRONMENT Chair: Ellen Thompson MB BS FRCPC Assistant Professor, University of Ottawa, Department of 1 Anaesthesiology, the Ottawa Hospital, CPM Chronic Pain Chair: David Mann C Eng FIET Management, Ottawa, Ontario, Local Arrangements Committee President FM-CFS Canada, Ottawa, Ontario Chair, 2007 Speakers: Hon Ed Broadbent PhD PC CC, Rocco Gerace MD Speakers: Allan Basbaum PhD FRS Chair, Department of Anatomy, Registrar W.M. Keck Foundation Center for Integrative Neuroscience, BRIEF DESCRIPTION: Conference delegates, pain patients and their University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California families and friends are invited, as well as the physicians caring for them. Jeffrey S Mogil PhD, Department of Psychology and Centre for We extend a particular invitation to physicians who have had concerns Research on Pain, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec about the CPSO and regulatory impact on prescribing pain medications. 1A 8:45 AM – SESSION 102 PAIN RELIEF – A BASIC HUMAN RIGHT Hon Ed Broadbent PhD PC CC 4 Former Leader of the New Democratic Party of Canada, Founding President of the International Centre for Human Rights and TRENDS IN OPIOID RELATED