The Emergence of Self-Organizing E-Commerce Ecosystems in Remote Villages in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

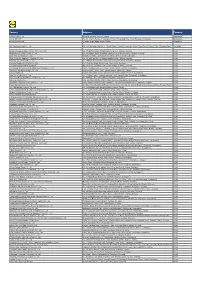

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Effectiveness of Live Poultry Market Interventions on Human Infection with Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus, China Wei Wang,1 Jean Artois,1 Xiling Wang, Adam J

RESEARCH Effectiveness of Live Poultry Market Interventions on Human Infection with Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus, China Wei Wang,1 Jean Artois,1 Xiling Wang, Adam J. Kucharski, Yao Pei, Xin Tong, Victor Virlogeux, Peng Wu, Benjamin J. Cowling, Marius Gilbert,2 Hongjie Yu2 September 2017) as of March 2, 2018 (2). Compared Various interventions for live poultry markets (LPMs) have with the previous 4 epidemic waves, the 2016–17 fifth emerged to control outbreaks of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in mainland China since March 2013. We assessed wave raised global concerns because of several char- the effectiveness of various LPM interventions in reduc- acteristics. First, a surge in laboratory-confirmed cas- ing transmission of H7N9 virus across 5 annual waves es of H7N9 virus infection was observed in wave 5, during 2013–2018, especially in the final wave. With along with some clusters of limited human-to-human the exception of waves 1 and 4, various LPM interven- transmission (3,4). Second, a highly pathogenic avi- tions reduced daily incidence rates significantly across an influenza H7N9 virus infection was confirmed in waves. Four LPM interventions led to a mean reduction Guangdong Province and has caused further human of 34%–98% in the daily number of infections in wave 5. infections in 3 provinces (5,6). The genetic divergence Of these, permanent closure provided the most effective of H7N9 virus, its geographic spread (7), and a much reduction in human infection with H7N9 virus, followed longer epidemic duration raised concerns about an by long-period, short-period, and recursive closures in enhanced potential pandemic threat in 2016–17. -

List of Business Partners and Factories – October 2020

Otto Group – List of business partners and factories – October 2020 This list contains business partners (only private labels) as well as the final production factories, which have been active for the Otto Group companies bonprix, Otto, myToys, Heine, Schwab and/or Witt. A business partner/factory is considered active if it has been active within the past 12 months and remains active as of the date the list is created. Only factories that are located in so-called risk countries according to the amfori BSCI classification are included. The Otto Group also produces in non-risk countries, e.g. the EU. All factory related information is based on data that suppliers share with Otto Group companies. The list is updated regularly but not on a daily basis. Type of Supplier Name Country City Factory Address Type of Social Audit/Certificate Business Partner 3S IMPORT & EXPORT SHIJIA CO., LTD China Shijiazhuang n.a. n.a. Business Partner A&R MODEN GMBH Germany Loerrach n.a. n.a. Business Partner A.KUDRESOVO FIRMA Lithuania Kaunas n.a. n.a. Business Partner AANYA DESIGNS MANUFACTURERS & EXPORTERS India Moradabad n.a. n.a. Business Partner AB KAUNO BALDAI Lithuania Kaunas n.a. n.a. Business Partner ABG24 Spolka z ograniczona odpowiedzialnosic (0010053817) Poland Lodz n.a. n.a. Business Partner ACTONA COMPANY A/S Denmark Holstebro n.a. n.a. Business Partner ADALTEKS LTD Bulgaria Sofia n.a. n.a. Business Partner ADAM EXPORTS SYNTHOFINE IND. ESTATE, B (0020010395) India Mumbai n.a. n.a. Business Partner ADIYAMAN DENIZ TEKSTIL SAN VE DIS TIC. -

The Case of Heyang Village

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4423–4442 1932–8036/20170005 The Political Economy and Cultural Politics of Rural Nostalgia in Xi-Era China: The Case of Heyang Village LINDA QIAN University of Oxford, UK This article offers a new theoretical framework to understand nostalgia as a political- economic and a cultural-political discourse in China. Introducing nostalgia as a “structure of feeling” in postreform China, the article analyzes its elevation as a new trope to address the economic and cultural contradictions of capitalistic global integration in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. It then traces the trickling down of nostalgia, from its initial invocation by Xi Jinping to its ideological propagation in major state- media productions and, finally, down to its appropriation and mobilization at the county and village levels. Finally, in grounding the research in Heyang Village, Zhejiang Province, the study demonstrates how, within this discourse of development with “nostalgia in mind,” a contentious enterprise of nostalgic tourism has figured as the centerpiece for rural development plans; Heyang’s future is now entangled in a contextually specific enterprise of the economy of nostalgia. Keywords: Chinese development, cultural heritage, nostalgia, rural tourism, Heyang In 2015, China Central Television’s (CCTV’s) annual Spring Festival Gala featured a song entitled Xiangchou 乡愁 (“Nostalgia”), which spoke of the bittersweet sense of nostalgic longing for the home village. Featured in the visual background were video clips of several villages in contemporary China, still deemed to possess “authentic” qualities of traditional Chinese village culture. CCTV initially shot these clips for the documentary series Jizhu Xiangchou (Nostalgia in Mind), which aired on CCTV-4 in the beginning of that same year. -

SUPPLIER LIST OCTOBER 2019 Cotton on Group - Supplier List 2

SUPPLIER LIST OCTOBER 2019 Cotton On Group - Supplier List _2 REGION SUPPLIER NAME FACTORY NAME SUPPLIER ADDRESS PRODUCT TOTAL % OF % OF % OF TYPE WORKERS FEMALE MIGRANT TEMP WORKERS WORKERS WORKERS BANGLADESH APTECH DESIGN LTD DESIGNER FASHION LTD GOHAILBARI SHIMULIA APPAREL 3422 72% 0% 0% SAVAR DHAKA BANGLADESH APTECH DESIGN LTD Y-FRONTS ACCESSORIES (NEW HOUSE 24, WARD # 01, ARSHINAGOR MAIN ROAD APPAREL 24 0% 0% 0% LOCATION) ARSHINAGOR, KERANIGONJ DHAKA BANGLADESH BELAMY TEXTILES LTD BELAMY TEXTILES LTD KHOWAZ NAGAR, AZIMPARA APPAREL KARNAFULLY CHITTAGONG BANGLADESH BIG BOSS CORPORATION LTD (of aptech BIG BOSS CORPORATION LTD (NEW) APTECH INDUSTRIAL PARK APPAREL group) 30 SHARABO,KASIMPUR GAZIPUR BANGLADESH CLASSIC FASHIONS FOUR DESIGN PVT LTD (NEW) PLOT NO. B-201, 202, BSCIC HOSIERY I/E APPAREL 305 64% 0% 0% SHASONGAON, ENAYETNAGAR, FATULLAH NARAYANGANJ BANGLADESH CLASSIC FASHIONS FOUR DESIGN PVT LTD (TEMPORARY) PLOT NO. B327/328, BSCIC HOSIERY I/E APPAREL 380 60% 0% 0% SHASONGAON, ENAYETNAGAR, FATULLAH NARAYANGANJ BANGLADESH IMPRESS NEWTEX COMPOSITE TEXTILES B2B EXCELLANCE LTD MIRZAPUR PURBAPARA, APPAREL 1355 76% 0% 0% LTD 8 NO. MIRZAPUR MOUZA, GAZIPUR SADAR,GAZIPUR BANGLADESH IMPRESS NEWTEX COMPOSITE TEXTILES IMPRESS NEWTEX COMPOSITE TEXTILES GORAI INDUSTRIAL AREA APPAREL 2124 56% 0% 0% LTD LTD MIRZAPUR TANGAIL BANGLADESH IRIS FABRICS LIMITED IRIS FABRICS LIMITED ZIRANIBAZAR APPAREL 2984 47% 0% 0% KASHIMPUT, JOYDEVPUR GAZIPUR BANGLADESH JERICHO IMEX JERICHO IMEX LTD MONTREE BARI ROAD APPAREL 700 62% 0% 0% SOUTH SHANLA, SHANLA BAZAR -

Producent Adres Land

*Deze lijst bevat alle 'non-food' leveranciers die producten aan Lidl hebben geleverd in de periode tussen 1 maart 2019 en 29 februari 2020. Producent Adres Land 3W Home Fashion Heyuan Co., Ltd. Mingzhu Industrial Park, Heyuan West Road, Chuangye South Road, Heyuan, Guangdong China A.B Sales Corp. (A Unit Of Satyam Creations (Pvt) Ltd.) Plot No. 1642, Zone -09, Kolkata Leather Complex, Bantala, 24 Parganas (South), Kolkatta, West Bengal India AB Apparels Ltd. No. 225 Singair Road, Tetuljhora, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Above & Beyond Co., Ltd. Plot No. 116/A, 116/B, Settmu (10) Street, Myay Taing Block No. 42, Industrial Zone (1), Shwe Pyi Thar Township, Yangon Myanmar Ador Composite Ltd. 1, C&B Bazar, Gilarchala, Sreepur, Gazipur, Bd Gazipur District, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Advanced Composite Textile Ltd. Kashor Masterbari, Bhaluka, Mymensingh, Sylhet Bangladesh Afroze Textile Industries (Pvt) Ltd. Plot C-8, Scheme 33, S.I.T.E., Super Highway, Karachi, Sindh Pakistan Afroze Textile Industries (Pvt) Ltd. LA-1/A, Block 22, F.B. Area, Karachi, Sindh Pakistan Ahmed Fashions 34/1, Darus Salam Road, Dhaka Bangladesh Ai Qi Fujian Shoes Plastic Co., Ltd. Meiling Street, Shuanggou Industrial District, Sichuan, Jinjiang, Fujian China Al Hadi Textile (Pvt) Ltd. D-12 Site Super Highway Industrial Area, Karachi, Sindh Pakistan Alpine Clothings Polpithigama (Pvt) Ltd. Andarayaya, Polpithigama Sri Lanka Alpine Clothings Yapahuwa (Pvt) Ltd. Anuradhapura Road, Uduweriya, North Western Sri Lanka AMG Factory Ltd. Plot No. 51 & 52, Myay Taing Block No. 25, Shwe Lin Ban Industrial Zone, Hlaing Thar Yar Township, Yangon Myanmar Andy Accessory Co., Ltd. -

SUPPLIER LIST AUGUST 2019 Cotton on Group - Supplier List 2

SUPPLIER LIST AUGUST 2019 Cotton On Group - Supplier List _2 COUNTRY FACTORY NAME SUPPLIER ADDRESS STAGE TOTAL % OF % OF % OF TEMP WORKERS FEMALE MIGRANT WORKER WORKERS WORKER CHINA NINGBO FORTUNE INTERNATIONAL TRADE CO LTD RM 805-8078 728 LANE SONGJIANG EAST ROAD SUP YINZHOU NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO QIANZHEN CLOTHES CO LTD OUCHI VILLAGE CMT 104 64% 75% 6% GULIN TOWN, HAISHU DISTRICT NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA XIANGSHAN YUFA KNITTING LTD NO.35 ZHENYIN RD, JUEXI STREET CMT 57 60% 88% 12% XIANGSHAN COUNTY NINGBO CITY, ZHEJIANG CHINA SUNROSE INTERNATIONAL CO LTD ROOM 22/2 227 JINMEI BUILDING NO 58 LANE 136 SUP SHUNDE ROAD, HAISHU DISTRICT NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO HAISHU WANQIANYAO TEXTILE CO LTD NO 197 SAN SAN ROAD CMT 26 62% 85% 0% WANGCHAN INDUSTRIAL ZONE NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA ZHUJI JUNHANG SOCKS FACTORY DAMO VILLAGE LUXI NEW VILLAGE CMT 73 38% 66% 0% ZHUJI CITY ZHEJIANG CHINA SKYLEAD INDUSTRY CO LIMITED LAIMEI INDUSTRIAL PARK SUP CHENGHAI DISTRICT, SHANTOU CITY GUANGDONG CHINA CHUANGXIANG TOYS LIMITED LAIMEI INDUSTRIAL PARK CMT 49 33% 90% 0% CHENGHAI DISTRICT SHANTOU, GUANGDONG CHINA NINGBO ODESUN STATIONERY & GIFT CO LTD TONGJIA VILLAGE, PANHUO INDUSTRIAL ZONE SUP YINZHOU DISTRICT NINGBO CITY, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO ODESUN STATIONERY & GIFT CO LTD TONGJIA VILLAGE, PANHUO INDUSTRIAL ZONE CMT YINZHOU DISTRICT NINGBO CITY, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO WORTH INTERNATIONAL TRADE CO LTD RM. 1902 BUILDING B, CROWN WORLD TRADE PLAZA SUP NO. 1 LANE 28 BAIZHANG EAST ROAD NINGBO ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGHAI YUEMING METAL PRODUCT CO LTD NO. 5 HONGTA ROAD -

Shop Direct Factory List Dec 17

FTE No. Factory Name Factory Address Country Sector % M workers (BSQ) BAISHIQING CLOTHING First and Second Area, Donghaian Industrial Zone, Shenhu Town, Jinjiang China CHINA Garments 148 35% (UNITED) ZHUCHENG TIANYAO GARMENTS CO., LTD Zangkejia Road, Textile & Garment Industrial Park, Longdu Subdistrict, Zhucheng City, Shandong Province, China CHINA Garments 332 19% ABHIASMI INTERNATIONAL PVT. LTD Plot No. 186, Sector 25 Part II, Huda, Panipat-132103, Haryana India INDIA Home Textiles 336 94% ABHITEX INTERNATIONAL Pasina Kalan, GT Road Painpat, 132103, Panipat, Haryana, India INDIA Homewares 435 99% ABLE JEWELLERY MFG. LTD Flat A9, West Lianbang Industrial District, Yu Shan xi Road, Panyu, Guangdong Province, China CHINA Jewellery 178 40% ABLE JEWELLERY MFG. LTD Flat A9, West Lianbang Industrial District, Yu Shan xi Road, Panyu, Guangdong Province, China HONG KONG Jewellery 178 40% AFROZE BEDDING UNIT LA-7, Block 22, Federal B Area, Karachi, Pakistan PAKISTAN Home Textiles 980 97% AFROZE TOWEL UNIT Plot No. C-8, Scheme 33, S. I. T.E, Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan PAKISTAN Home Textiles 960 97% AGEME TEKSTIL KONFEKSIYON INS LTD STI (1) Sari Hamazli Mah, 47083 Sok No. 3/2A, Seyhan, Adana, Turkey TURKEY Garments 350 41% AGRA PRODUCTS LTD Plot 94, 99 NSEZ, Phase 2, Noida 201305, U. P., India INDIA Jewellery 377 100% AIRSPRUNG BEDS LTD Canal Road, Canal Road Industrial Estate, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, BA14 8RQ, United Kingdom UK Furniture 398 83% AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495 Balitha, Shah Belishwer, Dhaamrai, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 5305 56% AL RAHIM Plot A-188, Site Nooriabad, Pakistan PAKISTAN Home Textiles 1350 100% AL-KARAM TEXTILE MILLS PVT LTD Ht-11, Landhi Industrial Area, Karachi. -

Global Factory List As of August 3Rd, 2020

Global Factory List as of August 3rd, 2020 Target is committed to providing increased supply chain transparency. To meet this objective, Target publishes a list of all tier one factories that produce our owned-brand products, national brand products where Target is the importer of record, as well as tier two apparel textile mills and wet processing facilities. Target partners with its vendors and suppliers to maintain an accurate factory list. The list below represents factories as of August 3rd, 2020. This list is subject to change and updates will be provided on a quarterly basis. Factory Name State/Province City Address AMERICAN SAMOA American Samoa Plant Pago Pago 368 Route 1,Tutuila Island ARGENTINA Angel Estrada Cla. S.A, Buenos Aires Ciudad de Buenos Aires Ruta Nacional N 38 Km. 1,155,Provincia de La Rioja AUSTRIA Tiroler Glashuette GmbH Werk: Schneegattern Oberosterreich Lengau Kobernauserwaldstrase 25, BAHRAIN WestPoint Home Bahrain W.L.L. Al Manamah (Al Asimah) Riffa Building #1912, Road # 5146, Block 951,South Alba Industrial Area, Askar BANGLADESH Campex (BD) Limited Chittagong zila Chattogram Building-FS SFB#06, Sector#01, Road#02, Chittagong Export Processing Zone,, Canvas Garments (Pvt.) Ltd Chittagong zila Chattogram 301, North Baizid Bostami Road,,Nasirabad I/A, Canvas Building Chittagong Asian Apparels Chittagong zila Chattogram 132 Nasirabad Indstrial Area,Chattogram Clifton Cotton Mills Ltd Chittagong zila Chattogram CDA plot no-D28,28-d/2 Char Ragmatia Kalurghat, Clifton Textile Chittagong zila Chattogram 180 Nasirabad Industrial Area,Baizid Bostami Road Fashion Watch Limited Chittagong zila Chattogram 1363/A 1364 Askarabad, D.T. Road,Doublemoring, Chattogram, Bangladesh Fortune Apparels Ltd Chittagong zila Chattogram 135/142 Nasirabad Industrial Area,Chattogram KDS Garment Industries Ltd. -

September 2018 Factory Name Address Country Department Worker Category Dophil Xafzotaj, Rruga Shjak, Durress Albania Footwear Le

September 2018 Factory Name Address Country Department Worker Category Dophil Xafzotaj, Rruga Shjak, Durress Albania Footwear Less than 1000 workers Ama Syntex Ltd. Plot No. 936 to 939, Vill: Jarun, Kashimpur, Joydebpur, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Apparel Less than 1000 workers A-One (BD) Limited Plot No. 114-120, Depz, Ganakbari, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers Apparel Plus Ltd. (A T S APPARELS LIMITED) Holding No. C-18 Dilan Complex, Chandona Chowrasta, Dhaka Road, Gazipur Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers BD Designs Private Limited Plot No. 48-49, Sector-3, Karnaphuli Epz, Chittagong Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers Continental Garments Ind (Pvt.) Ltd. 8, Dewan Idris Road, Boro Rangamatia, Ashulia, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers Creative Woolwear 3/B Darus Salam Road, Mirpur-1 Dhaka Bangladesh Apparel Less than 1000 workers Dird Composite Textiles Ltd. Shatiabari, Dhaladia, Rajendrapur, Sreepur, Gazipur Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers DNV Clothing Ltd. Plot No. 100-101, Adamjee EPZ, Siddhirgonj, Narayangonj Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers Echotex Ltd. Chandra, Palli Biddut, Kaliakoir, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Apparel 5001- 10,000 workers Fakir Apparels Ltd. A-142-145, B-501-503, BSCIC Industrial Estate, Fatullah, Narayanganj Bangladesh Apparel 5001-10,000 workers Far East Knitting & Dyeing Industries Ltd. Polli Bidut, Purbo Chandra, Shafipur, Kaliakoir, Gazipur Bangladesh Apparel 5001- 10,000 workers Fortis Garments Ltd. Holiding No. 100/1, Block B, Saheed Mosarraf Hossain Road, Purbo Chandora, Sofipur, Kaliakoir, Gazipur Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers Global Outerwear Ltd. 89, Berulia Road, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Apparel 1001- 5000 workers Golden Times Sweater & Dyeing Ltd. Mulaied, Mawna, Chowrasta, Sreepur, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Apparel Less than 1000 workers Hams Garments Ltd. -

Global Sourcing Map Factory List - Bangladesh

Information last updated July 2018 Global Sourcing Map Factory List - Bangladesh Factory Name Address Country Total Men Women Number of Workers Afiya Knitwear Ltd 10/ 2 Durgapur Ashulia Savar Dhaka 1341 Bangladesh 579 288 (49.7)% 291 (50.3)% AKH Apparels Ltd 128 Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1340 Bangladesh 2188 971 (44.4)% 1217 (55.6)% AKH Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah-Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Bangladesh 5418 3000 (55.4)% 2418 (44.6)% Alpha Knitting Wear Limited 888 Shewrapara, 1St & 2Nd Floor Begum Rokeya Shoroni Mirpur Dhaka 1216 Bangladesh 2307 682 (29.6)% 1625 (70.4)% Ananta Denim Technology Ltd Noyabari Kanchpur Sonargaon Narayanganj Bangladesh 4833 2394 (49.5)% 2439 (50.5)% Ananta Huaxiang Ltd 222, 223, H2-H4, Adamjee Epz Shiddirgonj Narayanganj Dhaka Bangladesh 2039 1184 (58.1)% 855 (41.9)% Anowara Knit Composite Ltd Mulaid Mawna Sreepur Gazipur Bangladesh 1979 1088 (55.0)% 891 (45.0)% Apex Lingerie Limited Chandora Kaliakoir Gazipur Bangladesh 3937 2041 (51.8)% 1896 (48.2)% Arunima Sportswear Ltd Dewan Idris Road Zirabo Ashulia Savar Dhaka Bangladesh 4481 2561 (57.2)% 1920 (42.8)% Primark does not own any factories and is selective about the suppliers with whom we work. Every factory which manufactures product for Primark has to commit to meeting internationally recognised standards, before the first order is placed and throughout the time they work with us. The factories featured on Primark’s Global Sourcing Map are Primark’s suppliers’ production sites which represent over 95% of Primark products for sale in Primark stores. A factory is detailed on the Map only after it has produced products for Primark for a year and has become an established supplier.