Welsh Mines Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welsh Bulletin

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF THE BRITISH ISLES WELSH BULLETIN Editors: R. D. Pryce & G. Hutchinson No. 76, June 2005 Mibora minima - one oftlle earliest-flow~ring grosses in Wales (see p. 16) (Illustration from Sowerby's 'English Botany') 2 Contents CONTENTS Editorial ....................................................................................................................... ,3 43rd Welsh AGM, & 23rd Exhibition Meeting, 2005 ............................ " ............... ,.... 4 Welsh Field Meetings - 2005 ................................... " .................... " .................. 5 Peter Benoit's anniversary; a correction ............... """"'"'''''''''''''''' ...... "'''''''''' ... 5 An early observation of Ranunculus Iriparlitus DC. ? ............................................... 5 A Week's Brambling in East Pembrokeshire ................. , ....................................... 6 Recording in Caernarfonshire, v.c.49 ................................................................... 8 Note on Meliltis melissophyllum in Pembrokeshire, v.c. 45 ....................................... 10 Lusitanian affinities in Welsh Early Sand-grass? ................................................... 16 Welsh Plant Records - 2003-2004 ........................... " ..... " .............. " ............... 17 PLANTLIFE - WALES NEWSLETTER - 2 ........................ " ......... , ...................... 1 Most back issues of the BSBI Welsh Bulletin are still available on request (originals or photocopies). Please enquire before sending cheque -

RUNNER's “Alaska 2003 World WORLD Trophy Winning Shoe” PRODUCT of the YEAR 2003

, PB TRAINER - £55.00 £ _ .... The perfect off road shoe ideal for fell running, V ^ , orienteering and cross-country. The outsoie is the Walsh pyramid type, which has a reputation \ PB XTREME - £60.00 l worldwide for its unbeatable grip and a 14mm »\(SIZES 3-13 INC Vs SIZES) K m'ciso^e for extra cushioning. ^ \ Same high specification as PB Trainer but U upper constructed in ^ exclusive use of \ lightweight tear resistant xymid material to give 1 cross weave nylon, for tm | additional’support, J unbeatable strength. For I protection and additional support and durability to the toe, ^^^protection velon has been ^ ^ ^ h e e l and instep. Excellent v . Tadded around the toe, heel and • ’’“ to r more aggressive terrain. t| -J mstep. Manufactured on specially designed lasts to give that perfect fit. An ideal all-round training or race shoe. JNR PB TRAINER - £40.00 (SIZES 1, 2, 3 and 31/s) PB RACER - £55.00 (SIZES 3-13 INC Va SIZES) Same high specification as PB Trainer except A lightweight pure racing shoe ideal for fell k with a 100mm lightweight midsole and made \ racing, orienteering and cross-country. Similar V ^ p » ^ » ^ o n the junior PB last. Excellent to the PB Trainer except with lighter ^ ^ "" ^ ^ sta rte r for all junior ^ * " T Bl^ ^ * w .w eish t materials 10mm ‘ * \enthusiasts. I midsole and constructed I on a last developed for j performance racing to give -X that track shoe feei. ^ ^ ^ ^ S u p e r b pure racing shoe for j jjwnite performance 1 SWOOP ) WAS £60.00 J NOW £40.00 SWOOP 2 - £60.00 /// (SIZES 10, 101/a, 11 and '(SIZES 4-12 INC 121/a) 1/2 SIZES) ^ ■ ^ w F ell running shoe for the Serious off-road racer and | jlk e e n fellrunner. -

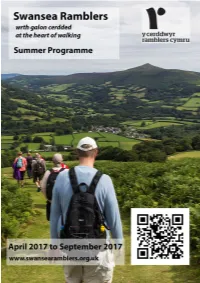

17Th Programme – Swansea Ramblers We Offer Short & Long Walks All Year Around and Welcome New Walkers to Try a Walk with U

17th Programme – Swansea Ramblers We offer short & long walks all year around and welcome new walkers to try a walk with us. 1 Front Cover Photograph: Table Mountain with view of Sugar Loaf v14 2 Swansea Ramblers’ membership benefits & events We have lots of walks and other events during the year so we thought you may like to see at a glance the sort of things you can do as a member of Swansea Ramblers: Programme of walks: We have long, medium & short walks to suit most tastes. The summer programme runs from April to September and the winter programme covers October to March. The programme is emailed & posted to members. Should you require an additional programme, this can be printed by going to our website. Evening walks: These are about 2-3 miles and we normally provide these in the summer. Monday Short walks: We also provide occasional 2-3 mile daytime walks as an introduction to walking, usually on a Monday. Saturday walks: We have a Saturday walk every week that is no more than 6 miles in length and these are a great way to begin exploring the countryside. Occasionally, in addition to the shorter walk, we may also provide a longer walk. Sunday walks: These alternate every other week between longer, harder walking for the more experienced walker and a medium walk which offers the next step up from the Saturday walks. Weekday walks: These take place on different days and can vary in length. Most are published in advance but we also have extra weekday walks at short notice. -

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

Taith Gerdded Cwm Hengae

Nodweddion Diddorol Points of Interest A Bu Aberllefenni yn A Aberllefenni was a sanctuary for many evacuees lloches i lawer o during the Second World War. In the 1980’s a film faciwîs yn ystod yr Ail called ‘Gwenoliaid’ (The Swallows) was filmed here, Ryfel Byd. Ffilmiwyd y depicting the lives of evacuees from London. ffilm ‘Gwenoliaid’ yma B Aberllefenni Slate Quarry is one of the oldest yn yr 1980au, gan working quarries in Wales. It operated on an bortreadu bywydau i t industrial basis from 1810 and employed 190 people n faciwîs o Lundain. e V at its peak. The quarry ceased extraction in 2002, k c i B N Chwarel Aberllefenni although some surface work continues today. The e r u yw un o’r chwareli t slate mill is still in operation and dresses Welsh c i P hynaf sydd ar waith / slate for domestic and industrial use. The bell on n u l L yng Nghymru. Bu’n the roof of the old quarry office would ring at the © gweithredu ar sail beginning and end of every working day. e a g n e H m w ddiwydiannol ers 1810, ac ar ei anterth C All around is slate waste. Slate from Aberllefenni C cyflogai 190 o bobl. Peidiodd y cloddio yn 2002, er was considered to be ‘the best in North Wales’. d e d d r e G h t i a bod peth gwaith yn parhau ar y wyneb hyd heddiw. However not all the material extracted was good T Mae’r felin lechi’n dal i weithio ac yn naddu llechi quality, so waste slate was dumped along the Cymru at ddefnydd domestig a diwydiannol. -

Property Portfolio, Aberllefenni, Corris, Mid-Wales

Property Portfolio, Aberllefenni, Corris, Mid-Wales Dafydd Hardy are delighted to offer this realistically priced portfolio of properties close to Corris, Mid-Wales. This unique investment opportunity comprises a portfolio of 16 residential properties, together with parcels of hillside and lowland agricultural land. Priced realistically for quick sale thus offering an excellent investment opportunity providing income as well as the possibility of increased property value growth, this portfolio is mainly located in the historic location of Aberllefenni, set high above the Dyfi Valley in this rural area of mid-Wales. The village of Aberllefenni is surrounded by beautiful countryside amidst the wooded slopes of the Dyfi Forest. The surrounding Dyfi Forest and Cader Idris mountain range are a mecca for walking, climbing, mountain biking, canoeing, birdwatc hing and fishing. Close by are scenic narrow gauge railways, King Arthur's Labyrinth underground adventure, and various museums. Within travelling distance by car are lovely seaside villages including delightful Aberdovey, the beaches at Barmouth and Fairbourne and the historic market towns of Machynlleth and Dolgellau. Corris, is some 2 miles distant on the A487, with the market town of Machynlleth approximately 7 miles distant. A regular bus service connects the village of Aberllefenni with Machynlleth, and with Dolgellau, which is a similar distance to the north. Property Portfolio, Aberllefenni, Corris, Mid-Wales The village of Aberllefenni, which stands on a national cycle route and the ancient Sarn Helen Walkway, nestles amidst the wooded slopes of the beautiful Dyfi Forest, close to the peac eful foothills of the Cader Idris mountain range. The surrounding area is a paradise for outdoor enthusiasts and is renowned for m ountain biking and canoeing whilst Mount Cader Idris provides wonderful climbing and walking. -

Ionawr 2012 Rhif 375

Caryl yn y neuadd... Tud 4 Ionawr 2012 Rhif 375 tud 3 tud 8 tud 11 tud 12 Pobl a Phethe Calennig Croesair Y Gair Olaf Blwyddyn Newydd Dda mewn hetiau amrywiol yn dilyn arweinydd yn gwisgo lliain wen a phen ceffyl wedi ei greu o papier mache! Mawr yw ein diolch i’r tîm dan gyfarwyddid Ruth Jen a Helen Jones a fu wrthi’n creu’r Fari’n arbennig ar ein cyfer – roedd hi’n werth ei gweld! Bu Ruth, Helen a’r tîm hefyd yn brysur ar y dydd Mercher cyn Nos Galan yn cynnal gweithdy yn y Neuadd, lle roedd croeso i unrhyw un daro draw i greu het arbennig i’w gwisgo ar y noson. Bu’r gweithdy’n brysur, ac mi gawson gyfl e i weld ffrwyth eu llafur ar y noson - amrywiaeth o hetiau o bob siap a maint wedi eu llunio o papier mache a fframiau pren. Wedi cyrraedd nôl i’r Neuadd cafwyd parti arbennig. Fe ymunwyd â ni gan y grãp gwerin A Llawer Mwy a fu’n ein diddanu gyda cherddoriaeth gwerin a dawnsio twmpath. O dan gyfarwyddid gwych y grãp mi ddawnsiodd mwyafrif y gynulleidfa o leiaf un cân! Mwynhawyd y twmpath yn fawr iawn gan yr hen a’r ifanc fel ei gilydd, ac roedd yn gyfl e gwych i ddod i nabod bobl eraill ar Dawnsio gwerin yn y Neuadd Goffa i ddathlu’r Calan y noson. Mi aeth y dawnsio a’r bwyta a ni Cafwyd Nos Galan tra gwahanol yn Nhal-y-bont eleni! Braf oedd at hanner nos, pan y gweld y Neuadd Goffa dan ei sang ar 31 Rhagfyr 2011 pan ddaeth tywysodd Harry James pentrefwyr a ffrindiau ynghñd er mwyn croesawi’r fl wyddyn ni i’r fl wyddyn newydd, newydd. -

Let's Electrify Scranton with Welsh Pride Festival Registrations

Periodicals Postage PAID at Basking Ridge, NJ The North American Welsh Newspaper® Papur Bro Cymry Gogledd America™ Incorporating Y DRYCH™ © 2011 NINNAU Publications, 11 Post Terrace, Basking Ridge, NJ 07920-2498 Vol. 37, No. 4 July-August 2012 NAFOW Mildred Bangert is Honored Festival Registrations Demand by NINNAU & Y DRYCH Mildred Bangert has dedicated a lifetime to promote Calls for Additional Facilities Welsh culture and to serve her local community. Now that she is retiring from her long held position as Curator of the By Will Fanning Welsh-American Heritage Museum she was instrumental SpringHill Suites by Marriott has been selected as in creating, this newspaper recognizes her public service additional Overflow Hotel for the 2012 North by designating her Recipient of the 2012 NINNAU American Festival of Wales (NAFOW) in Scranton, CITATION. Read below about her accomplishments. Pennsylvania. (Picture on page 3.) This brand new Marriott property, opening mid-June, is located in the nearby Montage Mountain area and just Welsh-American Heritage 10 minutes by car or shuttle bus (5 miles via Interstate 81) from the Hilton Scranton and Conference Center, the Museum Curator Retires Festival Headquarters Hotel. By Jeanne Jones Jindra Modern, comfortable guest suites, with sleeping, work- ing and sitting areas, offer a seamless blend of style and After serving as curator of the function along with luxurious bedding, a microwave, Welsh-American Heritage for mini-fridge, large work desk, free high-speed Internet nearly forty years, Mildred access and spa-like bathroom. Jenkins Bangert has announced Guest suites are $129 per night (plus tax) and are avail- her retirement. -

Y Tincer Ebrill

PAPUR BRO GENAU’R-GLYN, MELINDWR, TIRYMYNACH, TREFEURIG A’R BORTH PRIS 75c | Rhif 398 | Ebrill 2017 Mwy o Lansio prosiect t.12 Steddfod Anrhegu t.14 t.7 Tegwyn Llwyddiant! Lluniau Arvid Parry Jones Parry Arvid Lluniau Dau frawd o Gapel Bangor yn ennill dydd Sadwrn – Morgan Jac Lewis – dwy wobr gyntaf yn yr unawd a’r llefaru Bl 1 a 2 a Ava-Mae Griffiths, 3ydd ar lefaru Owen Jac Roberts , Rhydyfelin – cyntaf ar y Iestyn Dafydd Lewis - trydydd yn y Llefaru (Blwyddyn 3-4) nos Wener canu a’r llefaru Blwyddyn 3 a 4 dydd Sadwrn Bl 1 a 2. Academi Gerdd y Lli fu’n cystadlu ar y nos Wener Y Tincer | Ebrill 2017 | 398 dyddiadurdyddiadur Sefydlwyd Medi 1977 Rhifyn Mai - Deunydd i law: Mai 5 Dyddiad cyhoeddi: Mai 17 Aelod o Fforwm Papurau Bro Ceredigion EBRILL 30 Nos Sul Gŵyl Merêd gyda MAI 19 Nos Wener Rasus moch yn Neuadd ISSN 0963-925X Glanaethwy, Dai Jones, Gwenan Pen-llwyn, Capel Bangor o 7-10.00 dan Gibbard a Meinir Gwilym ym Mhafiliwn ofal Emlyn Jones dan nawdd Cymdeithas GOLYGYDD – Ceris Gruffudd Pontrhydfendigaid am 7.30. Rhieni Athrawon yr ysgol. Rhos Helyg, 23 Maesyrefail, Penrhyn-coch MAI 4 Dydd Iau Etholiadau Cyngor Sir a Chynghorau Tref a Chymuned MAI 20 Dydd Sadwrn Bedwen Lyfrau yng ( 828017 | [email protected] Nghanolfan y Celfyddydau TEIPYDD – Iona Bailey MAI 5 Nos Wener Cyngerdd gan Aber CYSODYDD – Elgan Griffiths (627916 Opera: Cyfarwyddwr Cerdd a Chyfeilydd : MEHEFIN 24 Dydd Sadwrn Taith flynyddol GADEIRYDD A THREFNYDD CYFEILLION Alistar Aulde, yn Eglwys Dewi Sant, Capel Cymdeithas y Penrhyn i Dde Ceredigion Y TINCER – Bethan Bebb Bangor am 7.30. -

Rabbit Warrens Report 2013

Medieval and Early Post-Medieval Rabbit Warrens: A Threat-Related Assessment 2013 MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL RABBIT WARRENS: A THREAT-RELATED ASSESSMENT 2013 PRN 105415 One of a group of 4 pillow mounds on high open moorland, near, Rhandirmwyn, Carmarthenshire. Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For Cadw Medieval and Early Post-Medieval Rabbit Warrens: A Threat-Related Assessment 2013 DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO.2013/14 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO.102814 DAT 121 Mawrth 2013 March 2013 MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL RABBIT WARRENS: A THREAT-RELATED ASSESSMENT 2013 Gan / By Fran Murphy, Marion Page & Hubert Wilson Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. -

1 PARC Ref No

PARC Ref No PGW (Gd) 35 (GWY) OS Map 124 Grid Ref SH 627 439 Former County Gwynedd Unitary Authority Gwynedd Community Council Llanfrothen Designations Snowdonia National Park; Listed Buildings: House, gatehouse, two remaining earlier houses (listed as 'two cottages NE of the Parc'), Beudy Newydd all Grade II; Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Primary Reference Numbers 4737 & 4742. Site Evaluation Grade II* Primary reasons for grading The rare survival of exceptional stone-built garden terraces probably of seventeenth-century date, associated with a group of interesting buildings and historical features set within a contemporary small walled park which includes a gatehouse and viewpoint. Clough Williams-Ellis made improvements in the 1950s and 60s. Type of Site Small park with industrial features overlaid, neglected terraced gardens of an early date, buildings of interest. Main Phases of Construction Possibly sixteenth and probably seventeenth century, later twentieth-century additions. SITE DESCRIPTION Parc is an unusual and extremely interesting site hidden away in the foothills to the north-east of the Traeth Mawr plain. The whole site is small, but has great charm, with its secluded setting but wide views, great variety of terrain and vegetation, and the contrast it provides with the steep and craggy slopes around. There are several houses, sited just above the steepest part of the valley of one of the streams, the Maesgwm, and close by are the remains of three small rectangular buildings, probably of medieval date, which represent the only known previous settlement in the area of the park. The choice of site for the post-medieval houses may have been dictated by various practical factors such as the need for shelter and a wish to leave as much of the level ground as possible clear for agricultural purposes. -

IL Combo Ndx V2

file IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE The Quarterly Journal of THE INDUSTRIAL LOCOMOTIVE SOCIETY COMBINED INDEX of Volumes 1 to 7 1976 – 1996 IL No.1 to No.79 PROVISIONAL EDITION www.industrial-loco.org.uk IL COMBO v2 for PDF.doc updated 13-12-2006 INTRODUCTION and ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This “Combo Index” has been assembled by combining the contents of the separate indexes originally created, for each individual volume, over a period of almost 30 years by a number of different people each using different approaches and methods. The first three volume indexes were produced on typewriters, though subsequent issues were produced by computers, and happily digital files had been preserved for these apart from one section of one index. It has therefore been necessary to create digital versions of 3 original indexes using “Optical Character Recognition” (OCR), which has not proved easy due to the relatively poor print, and extremely small text (font) size, of some of the indexes in particular. Thus the OCR results have required extensive proof-reading. Very fortunately, a team of volunteers to assist in the project was recruited from the membership of the Society, and grateful thanks are undoubtedly due to the major players in this exercise – Paul Burkhalter, John Hill, John Hutchings, Frank Jux, John Maddox and Robin Simmonds – with a special thankyou to Russell Wear, current Editor of "IL" and Chairman of the Society, who has both helped and given encouragement to the project in a myraid of different ways. None of this would have been possible but for the efforts of those who compiled the original individual indexes – Frank Jux, Ian Lloyd, (the late) James Lowe, John Scotford, and John Wood – and to the volume index print preparers such as Roger Hateley, who set a new level of presentation which is standing the test of time.