The Effect of Reorganization Proceedings on Security Interests: the Position Under English and U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judgment Claims in Receivership Proceedings*

JUDGMENT CLAIMS IN RECEIVERSHIP PROCEEDINGS* JOHN K. BEACH Connecticuf Supreme Court of Errors In view of the importance of the subject it is unfortunate that so few of the reported cases on equitable receiverships of corporations have dealt in any comprehensive way with the principles underlying the administrating of the fund for the benefit of creditors. The result is that controversy has outstripped authoritative decision, and the subject is unsettled. To this generalization an exception must be noted in respect of the special topic of the application of current rail- way income to current expenses, before the payment of mortgage 1 indebtedness. On another disputed topic, the provability of imma.ure claims, the law, or at least the right principle of decision, has been settled, by the notable opinion of Judge Noyes in Pennsylvania Steel Company v. New York City Railway Company,2 followed and rein- forced by that of Mr. Justice Holmes in William Filene'sSons Company v. Weed.' Notwithstanding these important exceptions, the dearth of authority on the general subject is such that Judge Noyes refers to a case cited in his opinion as "almost the only case in which rules have "been formulated with respect to the provability of claims against "insolvent corporations."4 Upon the particular phase of the subject here discussed, the decisions are to some extent in conflict, and no attempt seems to have been made in text books or decisions to examine the question in the light of principle. Black, for example, dismisses the subject by saying it. is generally conceded that a receiver and the corporation whose property is under his charge "are so far in privity that a judgment against the * This paper deals only with judgments against the defendant in the receiver- ship, regarded as evidence of the validity and amount of the judgment creditor's claims for dividends to be paid out of the fund in the receiver's hands. -

Self-Represented Creditor

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS A GUIDE FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED CREDITOR IN A BANKRUPTCY CASE June 2014 Table of Contents Subject Page Number Legal Authority, Statutes and Rules ....................................................................................... 1 Who is a Creditor? .......................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the Bankruptcy Process from the Creditor’s Perspective ................... 2 A Creditor’s Objections When a Person Files a Bankruptcy Petition ....................... 3 Limited Stay/No Stay ..................................................................................................... 3 Relief from Stay ................................................................................................................ 4 Violations of the Stay ...................................................................................................... 4 Discharge ............................................................................................................................. 4 Working with Professionals ....................................................................................................... 4 Attorneys ............................................................................................................................. 4 Pro se ................................................................................................................................................. -

CVA" Stands for a Number of Things, Including "Cerebro

COMPANY VOLUNTARY ARRANGEMENTS Michael Howlin, Q.C. Hastie Stable, Edinburgh 1. Introduction 1.1 The abbreviation "CVA" stands for a number of things, including "cerebro- vascular accident" (i.e., a stroke), "Creative Video Associations" (a company which recycles videotape), an organisation called "Croydon Voluntary Action", "credit value adjustment" (or indeed "counterparty valuation adjustment") in the context of banking, and a device known as a "controlled valve actuator". It also stands for "company voluntary arrangement", which is the subject-matter of this talk. 1.2 Recent high-profile examples of CVAs include those proposed by (the late) JJB Sports (for the second time), Blacks, Clinton Cards, PT McWilliams (a Northern Ireland engineering company), Oddbins (no explanation needed), Carvill Group (a Northern Ireland construction company) and McTavish 2 Ramsay, the Dundee door manufacturers. Even more recently, we have had the failed Glasgow Rangers CVA and CVAs for Travelodge and Fitness First. 2. The General Statutory Background 2.1 CVAs were created by the Insolvency Act 1986, which devoted all of seven sections to them. Since 2003, they have been governed by slightly expanded primary statutory provisions1 and a new Schedule (Schedule A1) to which I shall return shortly. There are also provisions in Part I of the Insolvency (Scotland) Rules 1986, as amended. 2.2 Section 1(1) defines a voluntary arrangement simply as "a composition in satisfaction of [the company's] debts or a scheme of arrangement of its affairs2". In practice, a CVA is a very flexible affair, the details of which will vary from case to case. Examples of what can be achieved by a CVA include: (1) unconditional foregiveness of debts, or certain classes of debts; (2) pro rata reduction (or partial reduction) of liabilities, or certain classes of liabilities; (3) other variations of liabilities (e.g. -

What a Creditor Needs to Know About Liquidating an Insolvent BVI Company

What a creditor needs to know about liquidating GUIDE an insolvent BVI company Last reviewed: October 2020 Contents Introduction 3 When is a company insolvent? 3 What is a statutory demand? 3 Written request for payment 3 Is it essential to serve a statutory demand? 3 What must a statutory demand say? 3 Setting aside a statutory demand 4 How may a company be put into liquidation? 4 Qualifying resolution 4 Appointment 4 Liquidator's powers 4 Court order 5 Who may apply? 5 Application 5 Debt should be undisputed 5 When does a company's liquidation start? 5 What are the consequences of a company being put into liquidation? 5 Assets do not vest in liquidator 5 Automatic consequences 5 Restriction on execution and attachment 6 Public documents 6 Other consequences 6 Effect on contracts 6 How do creditors claim in a company's liquidation? 7 Making a claim 7 Currency 7 Contingent debts 7 Interest 7 Admitting or rejecting claims 7 What is a creditors' committee? 7 Establishing the committee 7 2021934/79051506/1 BVI | CAYMAN ISLANDS | GUERNSEY | HONG KONG | JERSEY | LONDON mourant.com Functions 7 Powers 8 What is the order of distribution of the company's assets? 8 Pari passu principle 8 Excluded assets 8 Order of application 8 How are secured creditors affected by a company's liquidation? 8 General position 8 Liquidator challenge 8 Claiming in the liquidation 8 Who are preferential creditors? 9 Preferential creditors 9 Priority 9 What are the claims of current and past shareholders? 9 Do shareholders have to contribute towards the company's debts? -

How Should Property Be Valued in a Cram Down?

Mercer Law Review Volume 49 Number 3 Article 16 5-1998 How Should Property Be Valued In a Cram Down? Mark E. Beatty Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr Part of the Bankruptcy Law Commons Recommended Citation Beatty, Mark E. (1998) "How Should Property Be Valued In a Cram Down?," Mercer Law Review: Vol. 49 : No. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr/vol49/iss3/16 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Mercer Law School Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mercer Law Review by an authorized editor of Mercer Law School Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comments How Should Property Be Valued In a Cram Down? I. INTRODUCTION One of the most intriguing topics in bankruptcy law is the valuation of property in cram down cases, specifically Chapter 13 cases. This article will first present and discuss the different methods of valuation employed by the circuit courts before Associates Commercial Corp. v. Rash (Rash II)' was decided by the Supreme Court and the reasoning behind these methods. The next section will discuss the opinion in Rash and the chosen method of valuation in Chapter 13 cram down cases. The third section will discuss the implications of the decision in Rash. The Article will conclude with a proposed solution to the problems presented by the decision. 1. 117 S. Ct. 1879 (1997). 891 892 MERCER LAW REVIEW [Vol. 49 II. THE CIRcurr COURTS A. -

UK (England and Wales)

Restructuring and Insolvency 2006/07 Country Q&A UK (England and Wales) UK (England and Wales) Lyndon Norley, Partha Kar and Graham Lane, Kirkland and Ellis International LLP www.practicallaw.com/2-202-0910 SECURITY AND PRIORITIES ■ Floating charge. A floating charge can be taken over a variety of assets (both existing and future), which fluctuate from 1. What are the most common forms of security taken in rela- day to day. It is usually taken over a debtor's whole business tion to immovable and movable property? Are any specific and undertaking. formalities required for the creation of security by compa- nies? Unlike a fixed charge, a floating charge does not attach to a particular asset, but rather "floats" above one or more assets. During this time, the debtor is free to sell or dispose of the Immovable property assets without the creditor's consent. However, if a default specified in the charge document occurs, the floating charge The most common types of security for immovable property are: will "crystallise" into a fixed charge, which attaches to and encumbers specific assets. ■ Mortgage. A legal mortgage is the main form of security interest over real property. It historically involved legal title If a floating charge over all or substantially all of a com- to a debtor's property being transferred to the creditor as pany's assets has been created before 15 September 2003, security for a claim. The debtor retained possession of the it can be enforced by appointing an administrative receiver. property, but only recovered legal ownership when it repaid On default, the administrative receiver takes control of the the secured debt in full. -

Secured Financing and Priorities Among Creditors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1979 Secured Financing and Priorities among Creditors Anthony T. Kronman Thomas H. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anthony T. Kronman & Thomas H. Jackson, "Secured Financing and Priorities among Creditors," 88 Yale Law Journal 1143 (1979). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Secured Financing and Priorities Among Creditors* Thomas H. Jacksont and Anthony T. Kronmant One of the principal advantages of a secured transaction is the protection it provides against the claims of competing creditors. A creditor asserting a security interest in his debtor's property is likely to find himself in competition with a wide assortment of other claimants. For example, his security interest may be challenged by another creditor with a consensual security interest, by a creditor with a judgment or execution lien, by a creditor claiming a right to the collateral under some general statutory entitlement such as a repair- man's lien, by a seller to or a buyer from the debtor, or by the debtor's trustee in bankruptcy. To a considerable extent, the value of a security interest depends upon the degree to which it insulates the secured party from the claims of the debtor's other creditors.1 Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code contains detailed rules for resolving conflicts between secured creditors and various third parties-rules that tell the secured party what he must do in order to prevent his security interest from being overridden by a competing claimant, or, conversely, what a competitor must do in order to cir- cumvent an existing security interest in the debtor's property. -

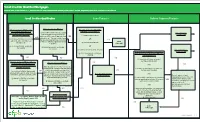

QM Small Creditor Flow Chart

SSmmaallll CCrreeddiittoorr QQuuaalliiffiieedd MMoorrttggaaggeess RReefflleeccttss rruulleess iinn eeffffeecctt oonn MMaarrcchh 11,, 22002211 bbuutt ddooeess nnoott rreefflleecctt aammeennddmmeennttss mmaaddee bbyy tthhee EEccoonnoommiicc GGrroowwtthh,, RReegguullaattoorryy RReelliieeff,, aanndd CCoonnssuummeerr PPrrootteeccttiioonn AAcctt.. Type of Compliance Presumption: SmSmaallll CCrreeddiitotorr QQuuaalliifificcaatitioonn Loan Features Balloon Payment Features Underwriting Points and Fees Portfolio Higher-Priced Loan Did you do ALL of the following?: Did you and your affiliates: Did you and your affiliates who Does the loan have ANY of the Rebuttable Presumption At the time of consummation: are creditors that extended following characteristics?: (1) Consider and verify the consumer’s YES Applies Extend 2,000 or fewer first-lien, closed- Does the loan amount fall within the following covered transactions during the Potential Small debt obligations and income or assets? STOP end residential mortgages that are points-and-fees limits? Was the loan subject to forward last calendar year have: (1) negative amortization; Creditor QM [via § 1026.43(c)(7), (e)(2)(v)]; = Non-Small Creditor QM (QM is presumed to comply subject to ATR requirements in the last YES commitment? AND YES YES = Non-Balloon-Payment QM with ATR requirements if calendar year? You can exclude loans Points-and-fees caps (adjusted annually) Assets below $2 billion (as annually OR AND it’s a higher-priced loan, but YES [§ 1026.43(e)(5)(i)(C), (f)(1)(v)] that you originated and kept in portfolio consumers can rebut the adjusted) at the end of the last STOP If Loan Amount ≥ $100,000, then = 3% of total or that your affiliate originated and kept (2) interest-only features; (2) Calculate the consumer’s monthly presumption by showing calendar year? = Non-QM If $100,000 > Loan Amount ≥ $60,000, then = $3,000 in portfolio. -

Partially Secured Creditors: Their Rights and Remedies Under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act John C

Louisiana Law Review Volume 37 | Number 5 Summer 1977 Partially Secured Creditors: Their Rights and Remedies Under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act John C. Anderson Repository Citation John C. Anderson, Partially Secured Creditors: Their Rights and Remedies Under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act, 37 La. L. Rev. (1977) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol37/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARTIALLY SECURED CREDITORS: THEIR RIGHTS AND REMEDIES UNDER CHAPTER XI OF THE BANKRUPTCY ACT John C. Anderson* Discussions of the rights of secured creditors under the Bankruptcy Act are conspicuous by their absence.' Ironically, the Act speaks the least about those creditors receiving the most.2 In bankruptcy liquidation cases under Chapters I-VII of the Bankruptcy Act, secured claims are entitled to the highest priority, being paid in preference to all other claims and 3 administrative expenses when the security for such claims is liquidated. Since most bankrupt estates are heavily encumbered by mortgages and liens, nearly all of the assets of the estates, after being liquidated, are paid toward secured claims. Accordingly, after the payment of secured debts, administrative expenses and then priority claims, there is usually little or nothing left to pay dividends to unsecured creditors. While there is a paucity of discussion about secured creditors in liquidation proceedings, similar discussions of the rights and remedies of secured creditors in arrangements under Chapter XI of the Bankruptcy Act are virtually nonexistent.4 Once again, secured creditors are integral par- * Member, Baton Rouge Bar. -

Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure May 2018

Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure May 2018 Professor Peter Walton, University of Wolverhampton Chris Umfreville, Aston University Dr Lézelle Jacobs, University of Wolverhampton Commissioned by R3, the insolvency and restructuring trade body, and sponsored by ICAEW This report would not have been possible without the support and guidance of: Allison Broad, Nick Cosgrove, Giles Frampton, John Kelly Bob Pinder, Andrew Tate, The Insolvency Service Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure About R3 R3 is the trade association for the UK’s insolvency, restructuring, advisory, and turnaround professionals. We represent insolvency practitioners, lawyers, turnaround and restructuring experts, students, and others in the profession. The insolvency, restructuring and turnaround profession is a vital part of the UK economy. The profession rescues businesses and jobs, creates the confidence to trade and lend by returning money fairly to creditors after insolvencies, investigates and disrupts fraud, and helps indebted individuals get back on their feet. The UK is an international centre for insolvency and restructuring work and our insolvency and restructuring framework is rated as one of the best in the world by the World Bank. R3 supports the profession in making sure that this remains the case. R3 raises awareness of the key issues facing the UK insolvency and restructuring profession and framework among the public, government, policymakers, media, and the wider business community. This work includes highlighting both policy issues for the profession and challenges facing business and personal finances. 2 Company Voluntary Arrangements: Evaluating Success and Failure Executive Summary • The biggest strength of a CVA is its flexibility. • Assessing the success or failure of CVAs is not straightforward and depends on a number of variables. -

Irish Examinership: Post-Eircom a Look at Ireland's Fastest and Largest

A look at Ireland’s fastest and largest restructuring through examinership and the implications for the process Irish examinership: post-eircom A look at Ireland’s fastest and largest restructuring through examinership and the implications for the process* David Baxter Tanya Sheridan A&L Goodbody, Dublin A&L Goodbody [email protected] The Irish telecommunications company eircom recently successfully concluded its restructuring through the Irish examinership process. This examinership is both the largest in terms of the overall quantum of debt that was restructured and also the largest successful restructuring through examinership in Ireland to date. The speed with which the restructuring of this strategically important company was concluded was due in large part to the degree of pre-negotiation between the company and its lenders before the process commenced. The eircom examinership demonstrated the degree to which an element of pre-negotiation can compliment the process. The advantages of the process, having been highlighted through the eircom examinership, might attract distressed companies from other EU jurisdictions to undertake a COMI shift to Ireland in order to avail of this process. he eircom examinership was notable for both the Irish High Court just 54 days after the companies Tsize of this debt restructuring and the speed in entered examinership. which the process was successfully concluded. In all, This restructuring also demonstrates the advantages €1.4bn of a total debt of approximately €4bn was of examinership as a ‘one-stop shop’: a flexible process written off the balance sheets of the eircom operating that allows for both the write-off of debt and the change companies. -

Summary Rescue Process”

COMPANY LAW REVIEW GROUP REPORT ADVISING ON A LEGAL STRUCTURE FOR THE RESCUE OF SMALL COMPANIES 22 OCTOBER 2020 1 | P a g e Contents Chairperson’s Letter to the Minister for Business, Enterprise and Innovation 4 1. Introduction to the Report 5 1.1. The Company Law Review Group ................................................................... 5 1.2 The Role of the CLRG ...................................................................................... 5 1.3 Policy Development........................................................................................ 5 1.4 Contact information ....................................................................................... 5 2. The Company Law Review Group Membership…………………………………………….….6 2.1 Membership of the Company Law Review Group ............................................ 6 3. The Work Programme ............................................................................................. 8 3.1 Introduction to the Work Programme ............................................................ 8 3.2 Company Law Review Group Work Programme 2018-2020 .............................. 8 3.3 Additional item to the Work Programme ........................................................ 9 3.4 Decision making process of the Company Law Review Group……………… ... ……..9 3.5 Committees of the Company Law Review Group ..... ….………………………………..…9 4. A Rescue Plan for SMEs ............................................................................................... 10 4.1 Introduction ................................................................................................