Mantids of Colorado Fact Sheet No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 It's All Geek to Me: Translating Names Of

IT’S ALL GEEK TO ME: TRANSLATING NAMES OF INSECTARIUM ARTHROPODS Prof. J. Phineas Michaelson, O.M.P. U.S. Biological and Geological Survey of the Territories Central Post Office, Denver City, Colorado Territory [or Year 2016 c/o Kallima Consultants, Inc., PO Box 33084, Northglenn, CO 80233-0084] ABSTRACT Kids today! Why don’t they know the basics of Greek and Latin? Either they don’t pay attention in class, or in many cases schools just don’t teach these classic languages of science anymore. For those who are Latin and Greek-challenged, noted (fictional) Victorian entomologist and explorer, Prof. J. Phineas Michaelson, will present English translations of the scientific names that have been given to some of the popular common arthropods available for public exhibits. This paper will explore how species get their names, as well as a brief look at some of the naturalists that named them. INTRODUCTION Our education system just isn’t what it used to be. Classic languages such as Latin and Greek are no longer a part of standard curriculum. Unfortunately, this puts modern students of science at somewhat of a disadvantage compared to our predecessors when it comes to scientific names. In the insectarium world, Latin and Greek names are used for the arthropods that we display, but for most young entomologists, these words are just a challenge to pronounce and lack meaning. Working with arthropods, we all know that Entomology is the study of these animals. Sounding similar but totally different, Etymology is the study of the origin of words, and the history of word meaning. -

Colour Transcript

Colour Transcript Date: Wednesday, 30 March 2011 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 30 March 2011 Colour Professor William Ayliffe Some of you in this audience will be aware that it is the 150th anniversary of the first colour photograph, which was projected at a lecture at the Royal Institute by James Clerk Maxwell. This is the photograph, showing a tartan ribbon, which was taken using the first SLR, invented by Maxwell’s friend. He took three pictures, using three different filters, and was then able to project this gorgeous image, showing three different colours for the first time ever. Colour and Colour Vision This lecture is concerned with the questions: “What is colour?” and “What is colour vision?” - not necessarily the same things. We are going to look at train crashes and colour blindness (which is quite gruesome); the antique use of colour in pigments – ancient red Welsh “Ladies”; the meaning of colour in medieval Europe; discovery of new pigments; talking about colour; language and colour; colour systems and the psychology of colour. So there is a fair amount of ground to cover here, which is appropriate because colour is probably one of the most complex issues that we deal with. The main purpose of this lecture is to give an overview of the whole field of colour, without going into depth with any aspects in particular. Obviously, colour is a function of light because, without light, we cannot see colour. Light is that part of the electromagnetic spectrum that we can see, and that forms only a tiny portion. -

Wetlands Invertebrates Banded Woollybear(Isabella Tiger Moth Larva)

Wetlands Invertebrates Banded Woollybear (Isabella Tiger Moth larva) basics The banded woollybear gets its name for two reasons: its furry appearance and the fact that, like a bear, it hibernates during the winter. Woollybears are the caterpillar stage of medium sized moths known as tiger moths. This family of moths rivals butterflies in beauty and grace. There are approximately 260 species of tiger moths in North America. Though the best-known woollybear is the banded woollybear, there are at least 8 woollybear species in the U.S. with similar dense, bristly hair covering their bodies. Woollybears are most commonly seen in the autumn, when they are just about finished with feeding for the year. It is at this time that they seek out a place to spend the winter in hibernation. They have been eating various green plants since June or early July to gather enough energy for their eventual transformation into butterflies. A full-grown banded woollybear caterpillar is nearly two inches long and covered with tubercles from which arise stiff hairs of about equal length. Its body has 13 segments. Middle segments are covered with red-orange hairs and the anterior and posterior ends with black hairs. The orange-colored oblongs visible between the tufts of setae (bristly hairs) are spiracles—entrances to the respiratory system. Hair color and band width are highly variable; often as the caterpillar matures, black hairs (especially at the posterior end) are replaced with orange hairs. In general, older caterpillars have more black than young ones. However, caterpillars that fed and grew in an area where the fall weather was wetter tend to have more black hair than caterpillars from dry areas. -

Arthropod Grasping and Manipulation: a Literature Review

Arthropod Grasping and Manipulation A Literature Review Aaron M. Dollar Harvard BioRobotics Laboratory Technical Report Department of Engineering and Applied Sciences Harvard University April 5, 2001 www.biorobotics.harvard.edu Introduction The purpose of this review is to report on the existing literature on the subject of arthropod grasping and manipulation. In order to gain a proper understanding of the state of the knowledge in this rather broad topic, it is necessary and appropriate to take a step backwards and become familiar with the basics of entomology and arthropod physiology. Once these principles have been understood it will then be possible to proceed towards the more specific literature that has been published in the field. The structure of the review follows this strategy. General background information will be presented first, followed by successively more specific topics, and ending with a review of the refereed journal articles related to arthropod grasping and manipulation. Background The phylum Arthropoda is the largest of the phyla, and includes all animals that have an exoskeleton, a segmented body in series, and six or more jointed legs. There are nine classes within the phylum, five of which the average human is relatively familiar with – insects, arachnids, crustaceans, centipedes, and millipedes. Of all known species of animals on the planet, 82% are arthropods (c. 980,000 species)! And this number just reflects the known species. Estimates put the number of arthropod species remaining to be discovered and named at around 9-30 million, or 10-30 times more than are currently known. And this is just the number of species; the population of each is another matter altogether. -

Lesson 3 Life Cycles of Insects

Praying Mantis 3A-1 Hi, boys and girls. It’s time to meet one of the most fascinating insects on the planet. That’s me. I’m a praying mantis, named for the way I hold my two front legs together as though I am praying. I might look like I am praying, but my incredibly fast front legs are designed to grab my food in the blink of an eye! Praying Mantis 3A-1 I’m here to talk to you about the life stages of insects—how insects develop from birth to adult. Many insects undergo a complete change in shape and appearance. I’m sure that you are already familiar with how a caterpillar changes into a butterfly. The name of the process in which a caterpillar changes, or morphs, into a butterfly is called metamorphosis. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 Insects like the butterfly pass through four stages in their life cycles: egg, larva [LAR-vah], pupa, and adult. Each stage looks completely different from the next. The young never resemble, or look like, their parents and almost always eat something entirely different. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 The female insect lays her eggs on a host plant. When the eggs hatch, the larvae [LAR-vee] that emerge look like worms. Different names are given to different insects in this worm- like stage, and for the butterfly, the larva state is called a caterpillar. Insect larvae: maggot, grub and caterpillar3A-3 Fly larvae are called maggots; beetle larvae are called grubs; and the larvae of butterflies and moths, as you just heard, are called caterpillars. -

The Effects of Native and Non-Native Grasses on Spiders, Their Prey, and Their Interactions

Spiders in California’s grassland mosaic: The effects of native and non-native grasses on spiders, their prey, and their interactions by Kirsten Elise Hill A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Joe R. McBride, Chair Professor Rosemary G. Gillespie Professor Mary E. Power Spring 2014 © 2014 Abstract Spiders in California’s grassland mosaic: The effects of native and non-native grasses on spiders, their prey, and their interactions by Kirsten Elise Hill Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science and Policy Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Joe R. McBride, Chair Found in nearly all terrestrial ecosystems, small in size and able to occupy a variety of hunting niches, spiders’ consumptive effects on other arthropods can have important impacts for ecosystems. This dissertation describes research into spider populations and their interactions with potential arthropod prey in California’s native and non-native grasslands. In meadows found in northern California, native and non-native grassland patches support different functional groups of arthropod predators, sap-feeders, pollinators, and scavengers and arthropod diversity is linked to native plant diversity. Wandering spiders’ ability to forage within the meadow’s interior is linked to the distance from the shaded woodland boundary. Native grasses offer a cooler conduit into the meadow interior than non-native annual grasses during midsummer heat. Juvenile spiders in particular, are more abundant in the more structurally complex native dominated areas of the grassland. -

Wax, Wings, and Swarms: Insects and Their Products As Art Media

Wax, Wings, and Swarms: Insects and their Products as Art Media Barrett Anthony Klein Pupating Lab Biology Department, University of Wisconsin—La Crosse, La Crosse, WI 54601 email: [email protected] When citing this paper, please use the following: Klein BA. Submitted. Wax, Wings, and Swarms: Insects and their Products as Art Media. Annu. Rev. Entom. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-ento-020821-060803 Keywords art, cochineal, cultural entomology, ethnoentomology, insect media art, silk 1 Abstract Every facet of human culture is in some way affected by our abundant, diverse insect neighbors. Our relationship with insects has been on display throughout the history of art, sometimes explicitly, but frequently in inconspicuous ways. This is because artists can depict insects overtly, but they can also allude to insects conceptually, or use insect products in a purely utilitarian manner. Insects themselves can serve as art media, and artists have explored or exploited insects for their products (silk, wax, honey, propolis, carmine, shellac, nest paper), body parts (e.g., wings), and whole bodies (dead, alive, individually, or as collectives). This review surveys insects and their products used as media in the visual arts, and considers the untapped potential for artistic exploration of media derived from insects. The history, value, and ethics of “insect media art” are topics relevant at a time when the natural world is at unprecedented risk. INTRODUCTION The value of studying cultural entomology and insect art No review of human culture would be complete without art, and no review of art would be complete without the inclusion of insects. Cultural entomology, a field of study formalized in 1980 (43), and ambitiously reviewed 35 years ago by Charles Hogue (44), clearly illustrates that artists have an inordinate fondness for insects. -

(Hemileuca Nuttalli) and GROUND MANTID (Litaneutria Minor) SEARCHES in the SOUTH OKANAGAN VALLEY, BRITISH COLUMBIA, 2009

NUTTALL’S BUCKMOTH (Hemileuca nuttalli) AND GROUND MANTID (Litaneutria minor) SEARCHES IN THE SOUTH OKANAGAN VALLEY, BRITISH COLUMBIA, 2009 By Vicky Young and Dawn Marks, BC Conservation Corps BC Ministry of Environment Internal Working Report September 23, 2009 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Nuttall’s Buckmoth (Hemileuca nuttalli) and Ground Mantid (Litaneutria minor) are two invertebrate species listed for inventory under the BC Conservation Framework (2009). The Nuttall’s Buckmoth is listed as a mid priority species on The COSEWIC Candidate List (COSEWIC 2009). The Ground Mantid may be recommended as a COSEWIC candidate (Rob Cannings, COSEWIC Arthropod subcommittee, pers. comm.). These species were included in a list of target species for the BC Conservation Corps grassland species inventory crew. The crew spent 4 days surveying antelope-brush habitats within the Southern Okanagan between August 24th and September 1st 2009. These searches did not result in any detection of either target species. This preliminary attempt to address the lack of data for these invertebrate species will help inform future inventory efforts. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Funding for this project was provided by the BC Ministry of Environment through the BC Conservation Corps and through the BC Conservation Framework. We appreciate administrative support from the BC Conservation Foundation (Barb Waters). Guidance and mentorship was provided by Orville Dyer, Wildlife Biologist with the BC Ministry of Environment. Training regarding moth behaviour and identification was provided by Dennis St. John. Rob Cannings, Curator of Entomology, Royal BC Museum, provided insect biodiversity, insect inventory, collection of voucher specimens and identification training. Jerry Mitchell and Aaron Reid, biologists with the BC Ministry of Environment, provided assistance with Wildlife Species Inventory database submissions. -

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815)

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2017 Etienne Stockland All rights reserved ABSTRACT Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Naturalists, state administrators and farmers in France and its colonies developed a myriad set of techniques over the course of the long eighteenth century to manage the circulation of useful and harmful insects. The development of normative protocols for classifying, depicting and observing insects provided a set of common tools and techniques for identifying and tracking useful and harmful insects across great distances. Administrative techniques for containing the movement of harmful insects such as quarantine, grain processing and fumigation developed at the intersection of science and statecraft, through the collaborative efforts of diplomats, state administrators, naturalists and chemical practitioners. The introduction of insectivorous animals into French colonies besieged by harmful insects was envisioned as strategy for restoring providential balance within environments suffering from human-induced disequilibria. Naturalists, administrators, and agricultural improvers also collaborated in projects to maximize the production of useful substances secreted by insects, namely silk, dyes and medicines. A study of -

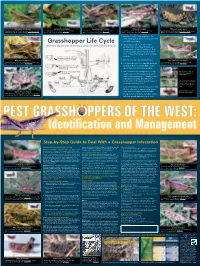

Grasshopper Life Cycle Overwinter As Nymphs

Twostriped grasshopper Redlegged grasshopper Clearwinged grasshopper Striped grasshopper Differential grasshopper Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops, trees, shrubs, and range. Peak hatch Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops and forage. Peak hatch range: Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops and forage. Peak hatch range: Does not take bran bait. Pest of range grasses. Peak hatch range: Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops, trees, and shrubs. Peak hatch range: range: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: June 21 – July 1. Female body length: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: June 21 – July 1. Female body length: 1. Hatching usually occurs mid-May to late June. A few species hatch in the summer and Grasshopper Life Cycle overwinter as nymphs. Western grasshoppers produce only one generation per year 2. Grasshoppers have to shed their hard exoskeleton to grow bigger through each nymphal phase (instar) to adulthood. They often hang upside down on grass stems to molt. It takes five to seven days to complete First and second instar nymphs (or an instar. hoppers) are usually less than 3/8” Migratory grasshopper long and no wing pads are visible. 3. Most species have five nymphal instars. Spottedwinged grasshopper Takes bran bait well. Pest of crops, range, and trees. Peak hatch range: Does not take bran bait. Pest of range grasses. Peak hatch range: May 15 – June 15. Female body length: 4. The last molt results in an adult with functional May 15 – June 15. Female body length: Third and fourth instars are usually wings that allow low, evasive flights. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Lawrence E. Hurd Phone: (540) 458-8484 Department of Biology FAX: 540-458-8012 Washington & Lee University Email: [email protected] Lexington, Virginia 24450 USA Education: B.A., Hiram College, 1969 Ph.D., Syracuse University, 1972 Positions (in reverse chronological order): Herwick Professor of Biology, Washington & Lee University 2008-present; Pesquisador Visitante Especial, Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM) 2013-2015. Editor- in-Chief,Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 2007 – present. Research supported by John T. Herwick Endowment, Brazilian research fellowship from CAPES, and by Lenfest faculty research grants from Washington and Lee University. Head of Department of Biology, Washington and Lee University, 1993-2008. Editorial Board of Oecologia, 1997 - 2003. Professor of Biology, Program in Ecology, School of Life and Health Sciences, and member of Graduate Faculty, University of Delaware, 1973-1993. Joint appointments: (1) College of Marine Studies (1974-1984); (2) Department of Entomology and Applied Ecology, College of Agriculture (1985-1993). Research supported by grants from NSF, NOAA (Sea Grant), and UDRF (U. Del.). Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell University, 1972 - 1973. Studies of population genetics and agro-ecosystems with D. Pimentel. Supported by grant from Ford Foundation to DP. Postdoctoral Fellow, Costa Rica, summer 1972. Behavioral ecology of tropical hummingbirds with L. L. Wolf. Supported by NSF grant to LLW. Memberships: American Association for the Advancement of Science Linnean Society -

An Overview of Systematics Studies Concerning the Insect Fauna of British Columbia

J ENTOMOL. Soc. B RIT. COLU MBIA 9 8. DECDmER 200 1 33 An overview of systematics studies concerning the insect fauna of British Columbia ROBERT A. CANNINGS ROYAL BRITISI-I COLUMBIA MUSEUM, 675 BELLEVILLE STREET, VICTORIA, BC, CANADA V8W 9W2 GEOFFREY G.E. SCUDDER DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF BRITISI-I COLUMBIA, VANCOUVER, BC, CANADA V6T IZ4 INTRODUCTION This summary of insect systematics pertaining to British Co lumbia is not intended as an hi storical account of entomologists and their work, but rath er is an overview of th e more important studies and publications dealing with the taxonomy, identifi cati on, distribution and faunistics of BC species. Some statistics on th e known size of various taxa are also give n. Many of the systematic references to th e province's insects ca nnot be presented in such a short summary as thi s and , as a res ult, the treatment is hi ghl y se lec tive. It deals large ly with publications appearing after 1950. We examine mainly terrestrial groups. Alth ough Geoff Scudder, Professor of Zoo logy at the University of Briti sh Co lumbi a, at Westwick Lake in the Cariboo, May 1970. Sc udder is a driving force in man y facets of in sect systemat ics in Briti sh Co lum bia and Canada. He is a world authority on th e Hemiptera. Photo: Rob Ca nnin gs. 34 J ENTOMOL. Soc BR IT. COLUMBIA 98, DECEMBER200 1 we mention the aquatic orders (those in which the larv ae live in water but the adults are aerial), they are more fully treated in the companion paper on aquatic in sects in thi s issue (Needham et al.) as are the major aquatic families of otherwise terrestrial orders (e.g.