Chapter Five Emergency Allegories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socialist Fairy Tales, Fables, and Allegories from Great Britain

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. ■ Introduction In 1974, I visited the mining area of South Wales to make a short educational radio programme about the nationalization of the mines, which took place under the Labour government of 1945– 50. One miner and political activist, Chris Evans, gave me a long interview ranging across the history of locality, mining, work, and his hopes for a socialist future. In describing the nature of life and work, he moved into recitation mode and said: I go to work, to earn money to buy bread to build up my strength, to go to work to earn money to buy bread to build up my strength to go to work . We laughed wryly. I enjoyed the way in which he had reduced the whole cycle of life and work into one rhythmic account. In literary terms, it turns the intricate interactions of existence into emblems, single vignettes that flow one to the other, contrasting with each other. It is, then, a particular kind of storytelling used with the in- tent of revealing or alerting a reader or listener to what the speaker thinks is an unsatisfactory state of affairs. The fact that the story doesn’t end with a conclusion hits the button because through its never- ending form (rather than through words themselves) it re- veals the folly, drudgery, and wrongness of what is being critiqued. 1 For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. -

Alternate History – Alternate Memory: Counterfactual Literature in the Context of German Normalization

ALTERNATE HISTORY – ALTERNATE MEMORY: COUNTERFACTUAL LITERATURE IN THE CONTEXT OF GERMAN NORMALIZATION by GUIDO SCHENKEL M.A., Freie Universität Berlin, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (German Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2012 © Guido Schenkel, 2012 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines a variety of Alternate Histories of the Third Reich from the perspective of memory theory. The term ‘Alternate History’ describes a genre of literature that presents fictional accounts of historical developments which deviate from the known course of hi story. These allohistorical narratives are inherently presentist, meaning that their central question of “What If?” can harness the repertoire of collective memory in order to act as both a reflection of and a commentary on contemporary social and political conditions. Moreover, Alternate Histories can act as a form of counter-memory insofar as the counterfactual mode can be used to highlight marginalized historical events. This study investigates a specific manifestation of this process. Contrasted with American and British examples, the primary focus is the analysis of the discursive functions of German-language counterfactual literature in the context of German normalization. The category of normalization connects a variety of commemorative trends in postwar Germany aimed at overcoming the legacy of National Socialism and re-formulating a positive German national identity. The central hypothesis is that Alternate Histories can perform a unique task in this particular discursive setting. In the context of German normalization, counterfactual stories of the history of the Third Reich are capable of functioning as alternate memories, meaning that they effectively replace the memory of real events with fantasies that are better suited to serve as exculpatory narratives for the German collective. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

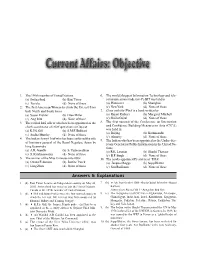

Higher Secondary: SET

RRB PSC Higher Secondary: SET 1. The 190th member of United Nations 6. The world’s biggest Information Technology and tele- (a) Switzerland (b) East Timor communications trade fair-Ce BIT was held in (c) Tuvalu (d) None of these (a) Hannover (b) Shanghai 2. The first American Woman to climb the Everest from (c) New York (d) None of these both North and South faces 7. Gone with the Wind is a book written by (a) Susan Ershler (b) Ellen Miller (a) Rajani Kothari (b) Margaret Mitchell (c) Ang Rita (d) None of these (c) Sheila Gujral (d) None of these 3. The retired IAS officer who has been appointed as the 8. The first summit of the Conference on Interaction chief co-ordinator of relief operations in Gujarat and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) (a) K.P.S. Gill (b) S.M.F. Bokhari was held in (a) Beijing (b) Kathmandu (c) Sudha Murthy (d) None of these (c) Almatty (d) None of these 4. The Indian Army Chief who has been conferred the title 9. The Indian who has been appointed as the Under-Sec- of honorary general of the Royal Nepalese Army by retary General for Public Information in the United Na- king Gyanendra tions. (a) A.R. Gandhi (b) S. Padmanabhan (a) R.K. Laxman (b) Shashi Tharoor (c) S. Krishnaswamy (d) None of these (c) B.P. Singh (d) None of these 5. The winner of the Miss Universe title 2002 10. The newly appointed President of ‘FIFA’ (a) Oxana Fedorova (b) Justine Pasek (a) Jacques Rogge (b) Sepp Blatter (c) Ling Zhou (d) None of these (c) Sen Ruffianne (d) None of these Answers & Explanations 1. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

AP Literature & Composition Literary Terms 1. Allegory: an Allegory Is A

AP Literature & Composition Literary Terms 1. Allegory: An allegory is a symbolism device where the meaning of a greater, often abstract, concept is conveyed with the aid of a more corporeal object or idea being used as an example. Usually a rhetoric device, an allegory suggests a meaning via metaphoric examples. 2. Alliteration: Alliteration is a literary device where words are used in quick succession and begin with letters belonging to the same sound group. Whether it is the consonant sound or a specific vowel group, the alliteration involves creating a repetition of similar sounds in the sentence. Alliterations are also created when the words all begin with the same letter. Alliterations are used to add character to the writing and often add an element of ‘fun’ to the piece. 3. Allusion: An allusion is a figure of speech whereby the author refers to a subject matter such as a place, event, or literary work by way of a passing reference. It is up to the reader to make a connection to the subject being mentioned. 4. Ambiguity: multiple meanings that a literary work may communicate, especially when two meanings are incompatible. 5. Amplification: Amplification refers to a literary practice wherein the writer embellishes the sentence by adding more information to it in order to increase its worth and understandability. When a plain sentence is too abrupt and fails to convey the full implications desired, amplification comes into play when the writer adds more to the structure to give it more meaning. 6. Anastrophe: Anastrophe is a form of literary device wherein the order of the noun and the adjective in the sentence is exchanged. -

Notes on Steven Moore, the Novel: an Alternative History, 1600-1800

Notes on Steven Moore, The Novel: An Alternative History, 1600-1800 (The essays I am posting on Humanities Commons are also on Librarything and Goodreads. These aren’t reviews. They are thoughts about the state of literary fiction, intended principally for writers and critics involved in seeing where literature might be able to go. EaCh one uses a book as an example of some Current problem in writing. The Context is my own writing projeCt, desCribed here, theorized here. All Comments and CritiCism are welCome!) A History of the Novel Without Literary Theory At one point The Novel: An Alternative History was projected in two volumes, with the second going up to 2012. Moore says in a couple of interviews he hasn’t been reading much contemporary fiction since 2004 in order to finish The Novel. It’s a reasonable inference he’s catching up, working away on volume 3, which I hope will be called The Novel: An Alternative History, 1800- 2020, if only to avoid the indecisive 1800 to the Present, the quirky alternatives 1800-2017, 1800- 2018, and so forth, or some inevitably failed subtitle like From Romanticism to Postmodernism and Beyond. My comments here are aimed at that imagined third volume. In preparing for these remarks I read volume 2, The Novel: An Alternative History, 1600-1800 (2013), skimmed volume 1, The Novel: An Alternative History, Beginnings to 1600 (2010), and read at least ten reviews of both books. The reception of the first two volumes of The Novel is marked by several leitmotifs, which I think are unhelpful in the sense that they distract from a deeper and more intriguing theme. -

1. Allegory – a Symbolic Narrative in Which the Surface Details Imply a Secondary Meaning, the Characters Represent Moral Qualities

Last Updated on: 1/8/2019 12:51:09 PM Poetry, Short Stories & Nonfiction: Literary Terms English II: Price Directions: CLASSWORK: highlight the terms in orange (TB pages R44-R49), write any term not in textbook on other pages – terms in BOLD denotes new terms. 1. Allegory – A symbolic narrative in which the surface details imply a secondary meaning, the characters represent moral qualities. This is different from symbolism (symbol) because this is a complete narrative. 2. Alliteration – is the repetition of initial consonant sounds: 3. Allusion – is a reference to a well-known person, place, event, literary work, or work of art. 4. Analogy – makes a comparison between two or more things that are similar in some ways but otherwise unalike. 5. Antagonist – A character or force against which another character struggles. Even in poems, there are antagonists 6. Anaphora – repetition of the same word or phrase at the beginning of a line throughout a work or the section of a work. 7. Assonance – is the repetition of vowel sounds followed by different consonants in two or more stressed syllables. 8. Apostrophe – is a figure of speech in which a speaker directly addresses an absent person or a personified quality, object, or idea 9. Ballad – is a songlike poem that tells a story, often one dealing with adventure and romance. 10. Blank Verse – is poetry written in unrhymed iambic pentameter lines. 11. Cacophony (cack-AH-fun-ee) Discordant sounds in the jarring juxtaposition of harsh letters or syllables, sometimes inadvertent, but often deliberately used in poetry for effect, 12. -

Current Affairs Questions and Answers for February 2010: 1. Which Bollywood Film Is Set to Become the First Indian Film to Hit T

ho”. With this latest honour the Mozart of Madras joins Current Affairs Questions and Answers for other Indian music greats like Pandit Ravi Shankar, February 2010: Zakir Hussain, Vikku Vinayak and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt who have won a Grammy in the past. 1. Which bollywood film is set to become the first A. R. Rahman also won Two Academy Awards, four Indian film to hit the Egyptian theaters after a gap of National Film Awards, thirteen Filmfare Awards, a 15 years? BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe. Answer: “My Name is Khan”. 9. Which bank became the first Indian bank to break 2. Who becomes the 3rd South African after Andrew into the world’s Top 50 list, according to the Brand Hudson and Jacques Rudoph to score a century on Finance Global Banking 500, an annual international Test debut? ranking by UK-based Brand Finance Plc, this year? Answer: Alviro Petersen Answer: The State Bank of India (SBI). 3. Which Northeastern state of India now has four HSBC retain its top slot for the third year and there are ‘Chief Ministers’, apparently to douse a simmering 20 Indian banks in the Brand Finance® Global Banking discontent within the main party in the coalition? 500. Answer: Meghalaya 10. Which country won the African Cup of Nations Veteran Congress leader D D Lapang had assumed soccer tournament for the third consecutive time office as chief minister on May 13, 2009. He is the chief with a 1-0 victory over Ghana in the final in Luanda, minister with statutory authority vested in him. -

Simply Put, an Allegory Is a Story That Closely Parallels

Allegory What Is Allegory? An allegory is a story that alludes to other literary works or comments on common conditions of life. When a work or its passages are allegorical, they are similar to an event, character or setting in a story that is universally known: a fable, a parable in the Bible, or a Greek myth. Allegories have two levels of narration occurring at the same time: the actual events, characters and setting presented in the story, and the ideas they are intended to convey or the significance they bear. Three literary forms that you might use when discussing allegory: Fable. A fable is a short story, often featuring animals with human traits, to which writers attach morals or explanations. Parable. Parables are most often associated with Jesus Christ, who used them in His teachings. They are short narratives that exemplify religious truths or insights. Myth. Myths are stories, either short or long, that are often associated with religion and philosophy and with various races and cultures. They embody the social and cultural values of the civilization during which they were written. When writing about allegory, determine whether all or part of the story is allegorical. Sustained allegory. This occurs when a story’s allegory continues throughout the work, from beginning to end. The sole purpose is to convey the dominant idea. The idea is emphasized rather than the story’s actual (literal) details. For example, The Pilgrim’s Progress is a story about Christian’s difficult journey from his home in the City of Destruction to his new home in the Heavenly City. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Allegory, Pathos, and Irony: the Resistance to Benjamin in Paul De Man

Allegory, Pathos, and Irony: The Resistance to Benjamin in Paul de Man Andrea Mirabile ABSTRACT Paul de Man’s writings on allegory are significantly influenced by the work of Wal- ter Benjamin. Nevertheless, Benjamin is conventionally perceived as semireligious and pathos-laden, whereas de Man is described as secular and emotionless. A close reading of selections from the two authors’ works (in particular Benjamin’s The Origin of German Tragic Drama and de Man’s Blindness and Insight) complicate this distinction, and the stereotypes supporting it. Both de Man and Benjamin help us to question the accepted borders between the emotively charged and the detached, the sacred and the profane, the redemptive and the nihilistic—hence their controversial yet unflagging resonance in contemporary culture. In the field of allegorical intuition the image is a fragment, a rune. Its beauty as a symbol evaporates when the light of divine learning falls upon it. —Walter Benjamin1 I intend to take the divine out of reading. —Paul de Man2 One of Paul de Man’s most original contributions to contemporary literary theory is a new formulation of the concept of allegory. De Man was perhaps the last great scholar of the twentieth century to deal with allegory, and he took upon himself the very difficult task of both giving a systematic definition of the concept and using it as a reading strategy. In order to fully understand and appreciate de Man’s work on allegory, it is essential to consider it in relation to Walter Benjamin’s writings on the subject. I propose to show how and where Benjamin’s influence is present in de Man’s reflections on allegory, and how de Man both absorbed and resisted this influence.