Fr John Breck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orthodox Books

Orthodox Books Orthodoxy:Introductions and Overviews Ancient Faith Topical Series Booklets Cclick here^ The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Christian Theology - Cambridge Companions to Religion, Mary Cunningham & Elizabeth Theokritoff Eastern Orthodox Christianity: A Western Perspective, Daniel B. Clendenin Encountering the Mystery: Understanding Orthodox Christianity Today, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology, Fr Andrew Louth Introducing the Orthodox Church-Its Faith and Life, Fr. Anthony Coniaris The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture, Fr John McGuckin The Orthodox Faith Series, Fr Thomas Hopko The Orthodox Way, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware Doctrine After Death, Vassilios Bakoyiannis The Deification of Man, Georgios Mantzaridis The Mystery of Christ, Fr. John Behr The Mystery of Death, Nikolaos Vassiliadis The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, Fr Vladimir Lossky The Nicene Faith, vols 1 and 11, Fr. John Behr Church History The Christian Tradition 2: The Spirit ofEastern Christendom 600-1700,Jaroslav Pelikan The Great Church in Captivity: A Study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the Eve of the Turkish Conquest to the Greek War ofIndependence, Steven Runciman History of the Byzantine State, George Ostrogorsky The Lives of Orthodox Saints, Ormylia Monastery The Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware Liturgy and Sacraments The Divine Liturgy: A Commentary in the Light of the Fathers, Hieromonk Gregorios and Elizabeth Theokritoff The Eucharist: -

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues As Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives Eben de Jager Abstract In contemporary Pentecostal and Charismatic circles glossolalia is Keywords often referred to as the tongues of angels, with 1 Corinthians 13:1 Tongues of angels, angeloglossy, xenolalia, glossolalia, being quoted. Yet writings on the tongues of angels available in hebraeophone. the first century and the Judaean context from which Paul wrote do not support such a narrative. In addition, the Corinthian About the Author1 context and the writings of the Church Fathers also paint a picture Eben de Jager not aligned with the contemporary view. An analysis of 1 Masters Degree, UNISA. He is a member of Spirasa (The Spirituality Corinthians 13:1–3 shows it to be a weak support for establishing Association of South Africa). the concept of contemporary ‘angelic language’. Other influences may have given rise to the idea of glossolalia as the tongues of angels, but the Bible does not appear to support such a view. 1 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the beliefs of the South African Theological Seminary. Conspectus—The Journal of the South African Theological Seminary ISSN 1996-8167 https://www.sats.edu.za/conspectus/ This article: https://www.sats.edu.za/de-jager-an-evaluation-of-speaking-in-tongues Conspectus, Volume 28, September 2019 35 1. Introduction There are many different views on the gift of tongues, or glossolalia, in Christian circles today. Cartledge (2000:136–138) lists twelve possibilities of what the linguistic nature of glossolalia might be, based on his study of various scholars’ work. -

Confession Resources

Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church St. Nikodemos Catechism Program "MAKE ME TO KNOW YOUR WAYS, O LORD, TEACH ME YOUR PATHS." PSALM 25:4 2 Patron Saint: Saint Nikodemos the Hagiorite Saint Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain was born on the Greek island of Naxos in the year 1748 and was named Nicholas at Baptism. At the age of twenty-six, he arrived on Mount Athos and received the monastic tonsure in the Dionysiou monastery with the name Nikodemos. As his first obedience, Nikodemos served as his monastery’s secretary. Two years after his entry into the Dionysiou monastery, the Metropolitan of Corinth, Saint Macarius Notaras (April 17), arrived there, and he assigned the young monk to edit the manuscript of the Philokalia, which he found in 1777 at the Vatopedi monastery. Editing this book was the beginning of many years of literary work by Saint Nikodemos. The young monk soon moved to the Pantokrator skete, where he was under obedience to the Elder Arsenius of the Peloponnesos, under whose guidance he zealously studied Holy Scripture and the works of the Holy Fathers. In 1783 Saint Nikodemos was tonsured to the Great Schema, and he lived in complete silence for six years. When Saint Macarius of Corinth next visited Athos, he gave the obedience of editing of the writings of Saint Symeon the New Theologian to Saint Nikodemos, who gave up his ascetic silence and occupied himself once more with literary work. From that time until his death he continued zealously to toil in this endeavor. Not long before his repose, Father Nikodemos, worn out by his literary work and ascetic efforts, went to live at the skete of the iconographers Hieromonks Stephen and Neophytus Skourtaius, who were brothers by birth. -

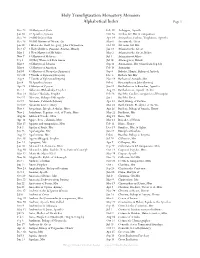

Holy Transfiguration Monastery Menaion Alphabetical Index Page 1

Holy Transfiguration Monastery Menaion Alphabetical Index Page 1 Dec 23 10 Martyrs of Crete Feb 19 Archippus, Apostle Jun 30 12 Apostles, Synaxis Oct 24 Arethas Grt Mtr & companions Dec 29 14,000 Infants Slain Apr 14 Aristarchus, Pudens, Trophimus, Apostles Dec 28 20,000 Martyrs of Nicomedia May 8 Arsenius the Great Jan 30 3 Hierarchs: Basil, Gregory, John Chrysostom Oct 20 Artemius Grt Mtr Dec 17 3 Holy Children (Ananias, Azarias, Misael) Jan 18 Athanasius the Great May 1 3 New Martyrs of Mt Athos May 2 Athanasius the Great, Relics Nov 7 33 Martyrs of Melitene Jul 5 Athanasius of Athos Sep 1 40 Holy Women & Dcn Amon Jul 16 Athenogenes, Hrmtr Mar 9 40 Martyrs of Sebastia Sep 11 Autonomus, Mtr (trans from Sep 12) Mar 6 42 Martyrs of Amorion Feb 14 Auxentius Jul 10 45 Martyrs of Nicopolis (Armenia) Sep 4 Babylas, Hrmtr, Bishop of Antioch Oct 22 7 Youths of Ephesus (Sleepers) Dec 4 Barbara Grt Mtr Aug 4 7 Youths of Ephesus (Sleepers) Nov 19 Barlaam of Antioch, Mtr Jan 4 70 Apostles Synaxis Feb 6 Barsanuphius & John (hymns) Apr 28 9 Martyrs of Cyzicus Jun 11 Bartholomew & Barnabas, Apostles Dec 2 Abbacum (Habakkuk), Prophet Aug 25 Bartholomew, Apostle, Relics Nov 19 Abdias (Obadiah), Prophet Feb 28 Basil the Confssr, companion of Procopius Oct 22 Abercius, Bishop of Hierapolis Jan 1 Basil the Great Oct 9 Abraham, Patriarch (hymns) Apr 12 Basil, Bishop of Parium Oct 29 Abramius & niece Mary Mar 22 Basil, Hrmtr, Presbyter of Ancyra Nov 3 Acepsimas, Joseph, Aethalas, Mtrs Apr 26 Basileus, Bishop of Amasia, Hrmtr Nov 2 Acindynus, Pegasius, et -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries ZECHER, JONATHAN,L How to cite: ZECHER, JONATHAN,L (2011) The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3247/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries Jonathan L. Zecher Department of Theology and Religion Durham University Submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy 2011 ABSTRACT The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries Jonathan L. Zecher This thesis examines the role which death plays in the development of a uniquely Christian identity in John Climacus’ seventh-century work, the Ladder of Divine Ascent and the Greek ascetic literature of the previous centuries. -

Peter of Damascus and Early Christian Spiritual Theology

Patristica et Mediaevalia, XXVI (2005) PETER OF DAMASCUS AND EARLY CHRISTIAN SPIRITUAL THEOLOGY Gm;G PETERS ,,, Having flourished in the mid-twelfth century, the Byzantine 1 spiritual theologian Peter of Damascus (fl, 1156/1157) is unique , Living somewhere in the Byzantine Empire during the twelfth century, Peter is known exclusively through the two works included in the late eighteenth-century Philokalia edited by Macarius of Corinth and 2 Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain • The two books carry several titles in the manuscripts but in the Philokalia they are entitled "The Book of our Holy and God-bearing Father Peter of Damascus" and "The Second Book of our Holy Father Peter of Damascus, The Twenty-Four Synoptic Discourses Full of Spiritual Knowledge", Both of these books concern themselves uniquely with the spiritual life, which Peter thinks, with 3 great optimism, is applicable to both monks and non-monastics • Peter, however, is a monk. Thus, a review of the Byzantine monastic landscape of the twelfth century helps situate Peter in his immediate social, historical and spiritual setting. By the early twelfth century, Byzantine monasticism was experiencing a period of intense fervor. During the eleventh century, monasteries of note were founded, for example, by Christodoulus of Patmos, Nikon of the Black Mountain, Lazarus of Mt. Galesion and, * Ontario, Canada. 1 The published literature on Peter of Damascus is, at present, limited. See Gouillard, J. "Un auteur spirituel byzantin du xnc siecle, Pierre Damascene", If:chos d'Orient 38 (1939): 257-278 [reprinted in Jean Gouillard, La vie religieuse a Byzance {London: Variorum Reprints, 1981)] and Greg Peters, "Recovering a Lost Spiritual Theologian: Peter of Damascus and the Philokalia", St. -

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichkovsky. 1722–1794. an Early Mod- Ern Master of the Orthodox Spiritual Life

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichkovsky. 1722–1794. An Early Mod- ern Master of the Orthodox Spiritual Life John A. MCGuckin Many people today have become familiar with the figure of the Russian Pilgrim. The book, The Way of a Pilgrim purports to have been written as the 157 autobiographical record of a poor and barely educated Russian peasant of the 19th century. Treading his way across the Steppes, enduring countless hardships and adventures as he persevered, gripped only with the reading of his beloved book of the spiritual writers of the Early Church, he directed all his mental energies around the countless recitation: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” This famous story is designed to advocate how the prayer of the heart can happen if one wills it: a mystical transitioning from prayer on the lips, to prayer in the mind, to prayer of the heart: namely, prayer in the deepest levels of the human spirit’s personal communion with the Risen Christ. The work in its English translation had a remarkable resonance in 20th century Europe and America; so much so, that nowadays if one asks about the spirituality of the pilgrim, most would think first of Russia and its mystical tra- dition of the Jesus Prayer, and perhaps hardly at all of the Puritans! The book’s popularity was helped along, doubtless, by its starred appearance in J.D. Salin- ger’s Franny and Zooey in 1961. It first came out in 1884 in a Russian version entitled: “Candid Tales of a Pilgrim to His Spiritual Father.” In all likelihood it emanated originally from the St. -

Examples of Nondual Thinkers and Mystics B.C

Examples of Nondual Thinkers and Mystics B.C. Abraham, Jacob, Elijah 2000-800 (MesopotamiaVedic Period c.1500-c.500 (Indian Subcontinent) Pre-Classical Hinduism c.500-c.200 (Indian Subcontinent) Upanishads 800-300 (India) Pythagoras c.570-c.495 (Ionia) Buddha c. Late 6th century-Early 5th century (India) Heraclitus c.535-c.475 (Ionia) Parmenides c.515 (Magna Graecia) Socrates c.470-399 (Greece) Plato c.425-c.348 (Greece) The Republic; Timaeus Lao-Tsu c.5th to 6th century (China) Tao Te Ching A.D. FIRST CENTURY Philo of Alexandria c.25 B.C.-c.50 A.D. (Egypt) Jesus of Nazareth c.4 B.C.-c.33 A.D. (Roman Empire; Palestine) Paul of Tarsus c.5-66 (Roman Empire) Ignatius of Antioch c.35-c.107 (Syria; Rome) SECOND CENTURY Clement of Alexandria c.150-c.215 (Egypt) THIRD CENTURY Origen c.185-254 (Egypt) On First Principles; On Prayer Plotinus c.205-270 (Egypt; Roman Empire) Enneads Anthony the Great c.251-356 (Egypt) Desert Fathers and Mothers begin 3rd century (Egypt; Turkey; Syria; Palestine) FOURTH CENTURY Syncletica of Alexandria c.280-c.350 (Egypt) Athanasius of Alexandria c.296-373 (Egypt) Life of Antony; On the Incarnation of the Word Macarius of Egypt c.300-391 (Egypt) Ephrem the Syrian c.306-373 (Syria) Gregory Naziansus c.329-390 (Cappadocia) Basil of Caesarea c.330-379 (Cappadocia) On the Holy Spirit Gregory of Nyssa c.335-c.395 (Cappadocia) Abba Poemen c.340-450 (Egypt) Evagrius Ponticus 345-399 (Pontus; Constantinople; Egypt) The Praktikos Augustine of Hippo 354-430 (Numidia) Confessions; City of God Copyright © 2019 Center for Action and Contemplation Page 1 of 5 FIFTH CENTURY Pseudo-Dyonisius c. -

HISTORY of the EASTERN CHURCH A.D. 530 to the Present Remote Course Via Audio Recordings and Moddle-Zoom Due to COVID-19 Pandemic

HS 2751 Fall 2020 Fr. A. Thompson, O.P. Tues / Fri 9:40–11:00 HISTORY OF THE EASTERN CHURCH A.D. 530 to the Present Remote Course via Audio Recordings and Moddle-Zoom due to COVID-19 Pandemic Instructor: Fr. Augustine Thompson O.P. Phone: 510-596-1800 ZOOM Office Hours: Tuesday 11:00-12:00 By appointment only—when made I will send an invitation to the Zoom meeting and the exact time. COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys the history of "Eastern" Christianity from late antiquity (age of the emperor Justinian) until the present day. The focus will be on the formation three characteristic components of Eastern Orthodox Christianity: institutions, liturgy and piety, and mysticism and theology. The focus will be on Greek Christianity in the earlier part of the course and Slavic Christianity in the later. Relations with the Christian west will also be considered. This semester DSPT will be completely distance learning due to the Coronavirus. Recordings of the lectures will be emailed to the class in time for the scheduled session, but may be listened to at any time before the arrival of the next lecture recording. Discussions will be by ZOOM meetings at the scheduled time. You will receive an invitation to log-in; do so 10 minutes before class time. If in-person classes resume at some piont in the semester we will return to sessions at DSPT. The couse will be approximately 35% Zoom sessions, 65% recorded lectures. See Technology Requirements at the end of the Syllabus. Required Reading The Bible. Those unacquainted with this book should become familiar with it. -

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichk- Ovsky. 1722-1794. an Early Modern Mas- Ter of the Orthodox Spiritual Life

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichk- ovsky. 1722-1794. An Early Modern Mas- ter of The Orthodox Spiritual Life John A. McGuckin Many people today have become familiar with the figure of the Russian Pilgrim. The book, The Way of a Pilgrim purports to have been written as the 157 autobiographical record of a poor and barely educated Russian peasant of the 19th century. Treading his way across the Steppes, enduring countless hardships and adventures as he persevered, gripped only with the reading of his beloved book of the spiritual writers of the Early Church, he directed all his mental energies around the countless recitation: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” This famous story is designed to advocate how the prayer of the heart can happen if one wills it: a mystical transitioning from prayer on the lips, to prayer in the mind, to prayer of the heart: namely, prayer in the deepest levels of the human spirit’s personal communion with the Risen Christ. The work in its English translation had a remarkable resonance in 20th century Europe and America; so much so, that nowadays if one asks about the spirituality of the pilgrim, most would think first of Russia and its mystical tra- dition of the Jesus Prayer, and perhaps hardly at all of the Puritans! The book’s popularity was helped along, doubtless, by its starred appearance in J.D. Salin- ger’s Franny and Zooey in 1961. It first came out in 1884 in a Russian version entitled: “Candid Tales of a Pilgrim to His Spiritual Father.” In all likelihood it emanated originally from the St. -

He Dwells Between the Cherubim; Let the Earth Be Moved! the Lord Is Great in Zion, and He Is High Above All the Peoples

Volume III, Number 9 A friendly Orthodox Christian ‘Zine SEPTEMBER 2008 PSALM 99 The Footstool of the Lord The Lord reigns, let the people tremble! He dwells between the cherubim; Let the earth be moved! The Lord is great in Zion, And He is high above all the peoples. Let them praise Your great and awesome name—He is holy. The King’s strength also loves justice; You have established equity; You have executed justice and righteousness in Jacob. Exalt the Lord our God, And worship at His footstool*—He is holy. Moses and Aaron were among His priests, And Samuel was among those Who called upon His name; They called upon the Lord, and He answered them. He spoke to them in the cloudy pillar; They kept the testimonies And the ordinances He gave them. You answered them, O Lord our God; You were to them God-Who-Forgives, Though you took vengeance on their deeds. Exalt the Lord our God, And worship at His holy hill; For the Lord our God is holy. NKJV Orthodox Study Bible *see p. 3. THE FRUIT BASKET Edited and published monthly by AnOrthodox Christian The goal of this publication is to provide a friendly, light , Orthodox Christian ’Zine (a mini-magazine) that contains a blend of “some- thing to exercise our minds, something to make us laugh, and some- thing to make us meditate on spiritual matters.” It is also a venue for sharing our insights and interests. Articles or comments from our readers are welcome. We reserve the right to edit for suitability, clarity and space. -

The Theology of Eros

THE THEOLOGY OF EROS Vladimir Moss © Vladimir Moss, 2009 This book is dedicated to my godson James and his bride Katerina, on the occasion of their wedding in the Orthodox Church. 2 FOREWORD .............................................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................7 The Problem Stated....................................................................................................7 Naturalism, Manichaeism, Platonism, Stoicism.......................................................8 The “Realistic” and “Idealistic” Views of Eros.......................................................17 1. EROS IN THE BEGINNING ..............................................................................19 Introduction: The Limitations of our Knowledge ....................................................19 Male and Female......................................................................................................20 Dominion through Love...........................................................................................24 The Creation of Eve..................................................................................................37 Neither Male nor Female .........................................................................................42 The Image of God and Sexuality..............................................................................47 Angelic and Sexual Modes of