From the Fathers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues As Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives Eben de Jager Abstract In contemporary Pentecostal and Charismatic circles glossolalia is Keywords often referred to as the tongues of angels, with 1 Corinthians 13:1 Tongues of angels, angeloglossy, xenolalia, glossolalia, being quoted. Yet writings on the tongues of angels available in hebraeophone. the first century and the Judaean context from which Paul wrote do not support such a narrative. In addition, the Corinthian About the Author1 context and the writings of the Church Fathers also paint a picture Eben de Jager not aligned with the contemporary view. An analysis of 1 Masters Degree, UNISA. He is a member of Spirasa (The Spirituality Corinthians 13:1–3 shows it to be a weak support for establishing Association of South Africa). the concept of contemporary ‘angelic language’. Other influences may have given rise to the idea of glossolalia as the tongues of angels, but the Bible does not appear to support such a view. 1 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the beliefs of the South African Theological Seminary. Conspectus—The Journal of the South African Theological Seminary ISSN 1996-8167 https://www.sats.edu.za/conspectus/ This article: https://www.sats.edu.za/de-jager-an-evaluation-of-speaking-in-tongues Conspectus, Volume 28, September 2019 35 1. Introduction There are many different views on the gift of tongues, or glossolalia, in Christian circles today. Cartledge (2000:136–138) lists twelve possibilities of what the linguistic nature of glossolalia might be, based on his study of various scholars’ work. -

A Review of Brian Mclaren, Finding Our Way Again: the Return of the Ancient Practices Michael A

Recovering Ancient Church Practices: A Review of Brian McLaren, Finding Our Way Again: The Return of the Ancient Practices Michael A. G. Haykin Michael A. G. Haykin is Professor of In this introductory volume for a new living in our culture, the book has to be Church History at The Southern Baptist series being published by Thomas Nelson judged a failure. Theological Seminary. He is also Adjunct entitled “The Ancient Practices Series” First, it needs to be noted that stylisti- Professor of Church History at Toronto (that will include volumes on prayer, the cally the book reads well and McLaren Baptist Seminary in Ontario, Canada. Dr. Sabbath, and tithing), well-known author is alert to the latest modes of expression, Haykin is the author of One Heart and and speaker Brian McLaren sounds a call though I must admit some of them grated One Soul (Evangelical Press, 1994), for the recovery of some of the spiritual on this reader. His use of the word “sexy,” Spirit of God: The Exegesis of 1 and riches of our Christian past, in particular for example—“the sexy young word 2 Corinthians in the Pneumatomachian those associated with what are called the spiritual” (19)—is very much in tune with Controversy of the Fourth Century spiritual disciplines. In this regard, his the ways in which that word has come (Brill, 1994), and Jonathan Edwards: book, Finding Our Way Again: The Return of to be used, though I for one have trouble 1 The Holy Spirit and Revival (Evangelical the Ancient Practices, is part of an interest dissociating it from meaning actual sex- Press, 2005). -

Islam and Christian Theologians

• CTSA PROCEEDINGS 48 (1993): 41-54 • ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN THEOLOGIANS Once upon a time an itinerant grammarian came to a body of water and enlisted the services of a boatman to ferry him across. As they made their way, the grammarian asked the boatman, "Do you know the science of grammar?" The humble boatman thought for a moment and admitted somewhat dejectedly that he did not. Not much later, a growing storm began to imperil the small vessel. Said the boatman to the grammarian, "Do you know the science of swimming?" On the eve of the new millennium too much of our theological activity remains shockingly intramural. Instead of allowing an inherent energy to launch us into the larger reality of global religiosity, we insist on protecting our theology from the threat of contamination. If we continue to resist serious engagement with other theological traditions, and that of Islam in particular, our theology may prove as useful as grammar in a typhoon. But what would swimming look like in theological terms? In the words of Robert Neville, "One of the most important tasks of theology today is to develop strategies for determining how to enter into the meaning system of another tradition, not merely as a temporary member of that tradition, but in such a way as to see how they bear upon one another."1 I propose to approach this vast subject by describing the "Three M's" of Muslim-Christian theological engagement: Models (or methods from the past); Method (or a model for future experimentation); and Motives. I. -

The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments

Durham E-Theses The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments Metallidis, George How to cite: Metallidis, George (2003) The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1085/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY GEORGE METALLIDIS The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consentand information derived from it should be acknowledged. The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene: Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments PhD Thesis/FourthYear Supervisor: Prof. ANDREW LOUTH 0-I OCT2003 Durham 2003 The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene To my Mother Despoina The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 12 INTRODUCTION 14 CHAPTER ONE TheLife of St John Damascene 1. -

Holy Fathers 7Th Council

October 14, 2012 Sunday Sermon Fr Ambrose Young Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple Skete The Holy Fathers of the 7th Council Titus 3:8-15 Luke 8:5-15 In the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. On this Sunday the Church celebrates the Holy Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council and asks us to reflect upon that Council and also the whole concept we Orthodox have of what we constantly refer to as “the Holy Fathers”. This Council of the Church—the last general universal Council of Holy Orthodoxy--was held in the year 787 and dealt with the whole controversy surrounding the use of sacred images or icons. This is an important Council for us to know about because in the West, at the time of the Protestant Reformation, images in churches were severely criticized and in many cases destroyed and forbidden. To this day most Protestant churches are very bereft and bare of sacred imagery other than the Cross, and some do not even have a Cross. Mormons even see the Cross as an emblem of shame and do not make use of it in their churches and temples, nor do they wear a cross. Even some very modern Catholic Churches—perhaps in order not to offend Protestants?—have gone in the direction of stripping themselves of sacred art of all kinds. But in Orthodoxy we continue to preserve and cherish our rich tradition of iconography and other forms of sacred art, seeing these as both theologically and spiritually necessary and also an essential component of ancient Christian civilization. -

Confession Resources

Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church St. Nikodemos Catechism Program "MAKE ME TO KNOW YOUR WAYS, O LORD, TEACH ME YOUR PATHS." PSALM 25:4 2 Patron Saint: Saint Nikodemos the Hagiorite Saint Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain was born on the Greek island of Naxos in the year 1748 and was named Nicholas at Baptism. At the age of twenty-six, he arrived on Mount Athos and received the monastic tonsure in the Dionysiou monastery with the name Nikodemos. As his first obedience, Nikodemos served as his monastery’s secretary. Two years after his entry into the Dionysiou monastery, the Metropolitan of Corinth, Saint Macarius Notaras (April 17), arrived there, and he assigned the young monk to edit the manuscript of the Philokalia, which he found in 1777 at the Vatopedi monastery. Editing this book was the beginning of many years of literary work by Saint Nikodemos. The young monk soon moved to the Pantokrator skete, where he was under obedience to the Elder Arsenius of the Peloponnesos, under whose guidance he zealously studied Holy Scripture and the works of the Holy Fathers. In 1783 Saint Nikodemos was tonsured to the Great Schema, and he lived in complete silence for six years. When Saint Macarius of Corinth next visited Athos, he gave the obedience of editing of the writings of Saint Symeon the New Theologian to Saint Nikodemos, who gave up his ascetic silence and occupied himself once more with literary work. From that time until his death he continued zealously to toil in this endeavor. Not long before his repose, Father Nikodemos, worn out by his literary work and ascetic efforts, went to live at the skete of the iconographers Hieromonks Stephen and Neophytus Skourtaius, who were brothers by birth. -

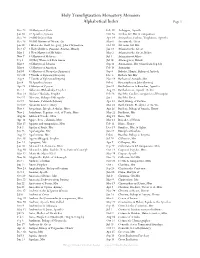

Holy Transfiguration Monastery Menaion Alphabetical Index Page 1

Holy Transfiguration Monastery Menaion Alphabetical Index Page 1 Dec 23 10 Martyrs of Crete Feb 19 Archippus, Apostle Jun 30 12 Apostles, Synaxis Oct 24 Arethas Grt Mtr & companions Dec 29 14,000 Infants Slain Apr 14 Aristarchus, Pudens, Trophimus, Apostles Dec 28 20,000 Martyrs of Nicomedia May 8 Arsenius the Great Jan 30 3 Hierarchs: Basil, Gregory, John Chrysostom Oct 20 Artemius Grt Mtr Dec 17 3 Holy Children (Ananias, Azarias, Misael) Jan 18 Athanasius the Great May 1 3 New Martyrs of Mt Athos May 2 Athanasius the Great, Relics Nov 7 33 Martyrs of Melitene Jul 5 Athanasius of Athos Sep 1 40 Holy Women & Dcn Amon Jul 16 Athenogenes, Hrmtr Mar 9 40 Martyrs of Sebastia Sep 11 Autonomus, Mtr (trans from Sep 12) Mar 6 42 Martyrs of Amorion Feb 14 Auxentius Jul 10 45 Martyrs of Nicopolis (Armenia) Sep 4 Babylas, Hrmtr, Bishop of Antioch Oct 22 7 Youths of Ephesus (Sleepers) Dec 4 Barbara Grt Mtr Aug 4 7 Youths of Ephesus (Sleepers) Nov 19 Barlaam of Antioch, Mtr Jan 4 70 Apostles Synaxis Feb 6 Barsanuphius & John (hymns) Apr 28 9 Martyrs of Cyzicus Jun 11 Bartholomew & Barnabas, Apostles Dec 2 Abbacum (Habakkuk), Prophet Aug 25 Bartholomew, Apostle, Relics Nov 19 Abdias (Obadiah), Prophet Feb 28 Basil the Confssr, companion of Procopius Oct 22 Abercius, Bishop of Hierapolis Jan 1 Basil the Great Oct 9 Abraham, Patriarch (hymns) Apr 12 Basil, Bishop of Parium Oct 29 Abramius & niece Mary Mar 22 Basil, Hrmtr, Presbyter of Ancyra Nov 3 Acepsimas, Joseph, Aethalas, Mtrs Apr 26 Basileus, Bishop of Amasia, Hrmtr Nov 2 Acindynus, Pegasius, et -

Maximus the Confessor and John of Damascus on Gnomic Will (Γνώμη) in Christ: Clarity and Ambiguity Paul M

44 Maximus the Confessor and John of Damascus on Gnomic Will (γνώμη) in Christ: Clarity and Ambiguity Paul M. Blowers Emmanuel Christian Seminary Johnson City, Tennessee For years I have been perplexed as to why Maximus the Confessor, in his articulate christological formulations in the seventh century, ultimately decided that Jesus Christ, as fully human, had only a natural human will (θέλημα φυσική), and so forcefully ruled against the possibility that he also had a “gnomic” (or “deliberative”) will (γνώμη) in the manner of fallen human beings. In the words of Maximus’ own beloved predecessor, Gregory Nazianzen, “what is not assumed is not healed.”1 Tough not alone in this concern, I’ve made a regular pest of myself broaching this issue in numerous patristics conferences (most recently the 2011 Oxford Patristics Conference) anytime an essay on Maximus would even remotely touch on the matter. Te answer I get represents a fairly hardened scholarly consensus. Accordingly, Maximus, in working out his understanding of the Chalcedonian defnition, still required a certain asymmetry in the composite hypostasis of Christ, since it is the divine hypostasis of the Son who united with and divinized the humanity of Jesus. In this case only a “natural” human will could be truly deifed, not a gnomic will prone to vacillation. I agree with this consensus in general, and it has been strengthened all the more in an excellent recent study by Ian McFarland comparing Maximus’ doctrine of the will with that of Augustine. McFarland has cogently argued the plausibility of Maximus’ denial of γνώμη in Christ as a function of his strong sense that “natural” human will, as modeled in Christ, is not antecedently “constrained” by the will of the divine Creator but a manifestation of the gracious stability of human will in concert with deifying divine grace. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries ZECHER, JONATHAN,L How to cite: ZECHER, JONATHAN,L (2011) The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3247/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries Jonathan L. Zecher Department of Theology and Religion Durham University Submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy 2011 ABSTRACT The Symbolics of Death and the Construction of Christian Asceticism: Greek Patristic Voices from the Fourth through Seventh Centuries Jonathan L. Zecher This thesis examines the role which death plays in the development of a uniquely Christian identity in John Climacus’ seventh-century work, the Ladder of Divine Ascent and the Greek ascetic literature of the previous centuries. -

Peter of Damascus and Early Christian Spiritual Theology

Patristica et Mediaevalia, XXVI (2005) PETER OF DAMASCUS AND EARLY CHRISTIAN SPIRITUAL THEOLOGY Gm;G PETERS ,,, Having flourished in the mid-twelfth century, the Byzantine 1 spiritual theologian Peter of Damascus (fl, 1156/1157) is unique , Living somewhere in the Byzantine Empire during the twelfth century, Peter is known exclusively through the two works included in the late eighteenth-century Philokalia edited by Macarius of Corinth and 2 Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain • The two books carry several titles in the manuscripts but in the Philokalia they are entitled "The Book of our Holy and God-bearing Father Peter of Damascus" and "The Second Book of our Holy Father Peter of Damascus, The Twenty-Four Synoptic Discourses Full of Spiritual Knowledge", Both of these books concern themselves uniquely with the spiritual life, which Peter thinks, with 3 great optimism, is applicable to both monks and non-monastics • Peter, however, is a monk. Thus, a review of the Byzantine monastic landscape of the twelfth century helps situate Peter in his immediate social, historical and spiritual setting. By the early twelfth century, Byzantine monasticism was experiencing a period of intense fervor. During the eleventh century, monasteries of note were founded, for example, by Christodoulus of Patmos, Nikon of the Black Mountain, Lazarus of Mt. Galesion and, * Ontario, Canada. 1 The published literature on Peter of Damascus is, at present, limited. See Gouillard, J. "Un auteur spirituel byzantin du xnc siecle, Pierre Damascene", If:chos d'Orient 38 (1939): 257-278 [reprinted in Jean Gouillard, La vie religieuse a Byzance {London: Variorum Reprints, 1981)] and Greg Peters, "Recovering a Lost Spiritual Theologian: Peter of Damascus and the Philokalia", St. -

The Divine in the Theological Thinking of Saint John of Damascus in Relationship with Relevant Teachings of Theodore Abu Qurrah

154 International Journal of Orthodox Theology 10:4 (2019) urn:nbn:de:0276-2019-4077 Dimitris Athanasiou The Divine in the Theological Thinking of Saint John of Damascus in relationship with relevant Teachings of Theodore Abu Qurrah Abstract Saint John of Damascus is considered to be one of the most significant personalities of the Orthodox Church, as well as the Christian world in general. As a teacher of the church through his writings, he tried to express clearly the teachings of Church so that they could be transferred effectively to it's active members. Around this frame, the teaching about divinity is included. John as an absolute theologian of the church, tried to explain this teaching Dimitris Athanasiou PhD in about divinity and transfer it to the Theology at the University world of God in the most possible of Athens, Greece The Divine in the Theological Thinking of Saint John of Damascus in 155 relationship with relevant Teachings of Theodore Abu Qurrah way. Putting things on a right basis, he approaches the whole issue under the Biblical observation, and earlier theology of Fathers as well. On the other hand, Abū Qurrah was also a symbolic personality of the Orthodox Church, who was raised around an Arab- Islamic environment, so the majority of his writings was basically in the Arabic language, while at the same time he was en gagged in defending the Christian faith, due to Islamic challenges. It was about two persons acting around the same geographical and cultural frame. That is why comparing the study of their Theological thinking is fairly essential for research. -

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichkovsky. 1722–1794. an Early Mod- Ern Master of the Orthodox Spiritual Life

The Life and Mission of St. Paisius Velichkovsky. 1722–1794. An Early Mod- ern Master of the Orthodox Spiritual Life John A. MCGuckin Many people today have become familiar with the figure of the Russian Pilgrim. The book, The Way of a Pilgrim purports to have been written as the 157 autobiographical record of a poor and barely educated Russian peasant of the 19th century. Treading his way across the Steppes, enduring countless hardships and adventures as he persevered, gripped only with the reading of his beloved book of the spiritual writers of the Early Church, he directed all his mental energies around the countless recitation: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” This famous story is designed to advocate how the prayer of the heart can happen if one wills it: a mystical transitioning from prayer on the lips, to prayer in the mind, to prayer of the heart: namely, prayer in the deepest levels of the human spirit’s personal communion with the Risen Christ. The work in its English translation had a remarkable resonance in 20th century Europe and America; so much so, that nowadays if one asks about the spirituality of the pilgrim, most would think first of Russia and its mystical tra- dition of the Jesus Prayer, and perhaps hardly at all of the Puritans! The book’s popularity was helped along, doubtless, by its starred appearance in J.D. Salin- ger’s Franny and Zooey in 1961. It first came out in 1884 in a Russian version entitled: “Candid Tales of a Pilgrim to His Spiritual Father.” In all likelihood it emanated originally from the St.