Mississippi Panorama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

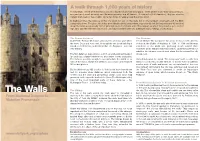

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment

Photography and Photomontage in Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment Landscape Institute Technical Guidance Note Public ConsuDRAFTltation Draft 2018-06-01 To the recipient of this draft guidance The Landscape Institute is keen to hear the views of LI members and non-members alike. We are happy to receive your comments in any form (eg annotated PDF, email with paragraph references ) via email to [email protected] which will be forwarded to the Chair of the working group. Alternatively, members may make comments on Talking Landscape: Topic “Photography and Photomontage Update”. You may provide any comments you consider would be useful, but may wish to use the following as a guide. 1) Do you expect to be able to use this guidance? If not, why not? 2) Please identify anything you consider to be unclear, or needing further explanation or justification. 3) Please identify anything you disagree with and state why. 4) Could the information be better-organised? If so, how? 5) Are there any important points that should be added? 6) Is there anything in the guidance which is not required? 7) Is there any unnecessary duplication? 8) Any other suggeDRAFTstions? Responses to be returned by 29 June 2018. Incidentally, the ##’s are to aid a final check of cross-references before publication. Contents 1 Introduction Appendices 2 Background Methodology App 01 Site equipment 3 Photography App 02 Camera settings - equipment and approaches needed to capture App 03 Dealing with panoramas suitable images App 04 Technical methodology template -

PANORAMA the Murphy Windmillthe Murphy Etration Restor See Pages 7-9 Pages See

SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER PANORAMA April-June, 2020 Vol. 32, No. 2 Inside This Issue The Murphy Windmill Restor ation Photo Ron by Henggeler Bret Harte’s Gold Rush See page 3 WPA Murals See page 3 1918 Flu Pandemic See page 11 See pages 7-9 SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Message from the President COVID-19 debarks from the tongue less trippingly than worked, and what didn’t? On page 11 of mellifluous Spanish Flu, the misnomer for the pandemic that this issue of Panorama, Lorri Ungaretti ravaged the world and San Francisco 102 years ago. But as we’ve gives a summary of how we dealt with read, COVID-19’s arrival here is much like the Spanish flu. the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. COVID-19 too resembles another pandemic, black death, or The San Francisco Historical bubonic plague. Those words conjure the medieval world. Or Society seeks to tell our history, our 17th-century London, where an outbreak killed almost 25% of story (the words have the same root) in the city’s population between 1665 and 1666. At the turn of ways that engage us, entertain us even. the 20th century, twenty years before arrival of the Spanish flu, At the same time we tell our story to the bubonic plague found its way to the United States and San make each of us, as the Romans would Francisco. Here, politicians and power brokers, concerned more say, a better civis, or citizen, and our John Briscoe about commerce than public health, tried to pass off evidence of city, as the Greeks would put it, a President, Board of greater polis, or body of citizens. -

MISSOURI TIMES the State Historical Society of Missouri May 2011 Vol

MISSOURI TIMES The State Historical Society of Missouri May 2011 Vol. 7, No. 1 2011: All About Bingham The Society loans its most valuable painting to the Truman Library, publishes a book in partnership with the Friends of Arrow Rock, and participates in an important symposium— all to promote better understanding of “The Missouri Artist,” George Caleb Bingham. Bingham masterpiece, Watching the Cargo, and several Bingham portraits to the exhibition, which was organized with skill and panache by the Truman Senator Blunt Page 3 Library’s museum curator, Clay Bauske. On the evening of March 9, a special preview of the exhibition opened to great fanfare with a reception at the Library attended by many important members of the Kansas City and Independence communities. Dr. Michael Divine, Director of the Truman Library, along with State Historical Society President Judge Stephen N. State Contest Page 5 Society Executive Director Gary R. Kremer and Curator of Art Joan Stack take advantage of a rare opportunity to study Order Limbaugh Jr. greeted guests and shared No. 11, up-close and unadorned, as it rests out of its frame in their enthusiasm for this cooperative preparation to travel. effort to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of a quintessentially In early March the State Historical Society American artist whose extraordinary of Missouri’s best known painting, General artworks brought national attention to Order No. 11, by George Caleb Bingham, left Missouri’s culture, society, and politics. Columbia for the first time in fifty years. The Special appreciation was extended to Ken special circumstance that justified the move and Cindy McClain of Independence whose was Order No. -

Research Issues1 Wybrane Zespoły Bramne Na Śląsku

TECHNICAL TRANSACTIONS 3/2019 ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING DOI: 10.4467/2353737XCT.19.032.10206 SUBMISSION OF THE FINAL VERSION: 15/02/2019 Andrzej Legendziewicz orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-296X [email protected] Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Technology Selected city gates in Silesia – research issues1 Wybrane zespoły bramne na Śląsku – problematyka badawcza Abstract1 The conservation work performed on the city gates of some Silesian cities in recent years has offered the opportunity to undertake architectural research. The researchers’ interest was particularly aroused by towers which form the framing of entrances to old-town areas and which are also a reflection of the ambitious aspirations and changing tastes of townspeople and a result of the evolution of architectural forms. Some of the gate buildings were demolished in the 19th century as a result of city development. This article presents the results of research into selected city gates: Grobnicka Gate in Głubczyce, Górna Gate in Głuchołazy, Lewińska Gate in Grodków, Krakowska and Wrocławska Gates in Namysłów, and Dolna Gate in Prudnik. The obtained research material supported an attempt to verify the propositions published in literature concerning the evolution of military buildings in Silesia between the 14th century and the beginning of the 17th century. Relicts of objects that have not survived were identified in two cases. Keywords: Silesia, architecture, city walls, Gothic, the Renaissance Streszczenie Prace konserwatorskie prowadzone na bramach w niektórych miastach Śląska w ostatnich latach były okazją do przeprowadzenia badań architektonicznych. Zainteresowanie badaczy budziły zwłaszcza wieże, które tworzyły wejścia na obszary staromiejskie, a także były obrazem ambitnych aspiracji i zmieniających się gustów mieszczan oraz rezultatem ewolucji form architektonicznych. -

Panorama Photography by Andrew Mcdonald

Panorama Photography by Andrew McDonald Crater Lake - Andrew McDonald (10520 x 3736 - 39.3MP) What is a Panorama? A panorama is any wide-angle view or representation of a physical space, whether in painting, drawing, photography, film/video, or a three-dimensional model. Downtown Kansas City, MO – Andrew McDonald (16614 x 4195 - 69.6MP) How do I make a panorama? Cropping of normal image (4256 x 2832 - 12.0MP) Union Pacific 3985-Andrew McDonald (4256 x 1583 - 6.7MP) • Some Cameras have had this built in • APS Cameras had a setting that would indicate to the printer that the image should be printed as a panorama and would mask the screen off. Some 35mm P&S cameras would show a mask to help with composition. • Advantages • No special equipment or technique required • Best (only?) option for scenes with lots of movement • Disadvantages • Reduction in resolution since you are cutting away portions of the image • Depending on resolution may only be adequate for web or smaller prints How do I make a panorama? Multiple Image Stitching + + = • Digital cameras do this automatically or assist Snake River Overlook – Andrew McDonald (7086 x 2833 - 20.0MP) • Some newer cameras do this by “sweeping the camera” across the scene while holding the shutter button. Images are stitched in-camera. • Other cameras show the left or right edge of prior image to help with composition of next image. Stitching may be done in-camera or multiple images are created. • Advantages • Resolution can be very high by using telephoto lenses to take smaller slices of the scene -

Download Download

TEMPERANCE, ABOLITION, OH MY!: JAMES GOODWYN CLONNEY’S PROBLEMS WITH PAINTING THE FOURTH OF JULY Erika Schneider Framingham State College n 1839, James Goodwyn Clonney (1812–1867) began work on a large-scale, multi-figure composition, Militia Training (originally Ititled Fourth of July ), destined to be the most ambitious piece of his career [ Figure 1 ]. British-born and recently naturalized as an American citizen, Clonney wanted the American art world to consider him a major artist, and he chose a subject replete with American tradition and patriotism. Examining the numer- ous preparatory sketches for the painting reveals that Clonney changed key figures from Caucasian to African American—both to make the work more typically American and to exploit the popular humor of the stereotypes. However, critics found fault with the subject’s overall lack of decorum, tellingly with the drunken behavior and not with the African American stereotypes. The Fourth of July had increasingly become a problematic holi- day for many influential political forces such as temperance and abolitionist groups. Perhaps reflecting some of these pressures, when the image was engraved in 1843, the title changed to Militia Training , the title it is known by today. This essay will pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 77, no. 3, 2010. Copyright © 2010 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 14:57:03 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PAH77.3_02Schneider.indd 303 6/29/10 11:00:40 AM pennsylvania history demonstrate how Clonney reflected his time period, attempted to pander to the public, yet failed to achieve critical success. -

The Bald Knobbers of Southwest Missouri, 1885-1889: a Study of Vigilante Justice in the Ozarks

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 "The aldB Knobbers of Southwest Missouri, 1885-1889: A Study of Vigilante Justice in the Ozarks." Matthew aJ mes Hernando Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hernando, Matthew James, ""The aldB Knobbers of Southwest Missouri, 1885-1889: A Study of Vigilante Justice in the Ozarks."" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3884. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3884 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE BALD KNOBBERS OF SOUTHWEST MISSOURI, 1885-1889: A STUDY OF VIGILANTE JUSTICE IN THE OZARKS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Matthew J. Hernando B.A., Evangel University, 2002 M.A., Assemblies of God Theological Seminary, 2003 M.A., Louisiana Tech University, 2005 May 2011 for my parents, James and Moira Hernando ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Anyone who completes a project of this nature quickly accumulates a list of both personal and professional debts so long that mentioning them all becomes impossible. The people mentioned here, therefore, do not constitute an exhaustive list of all the people who have helped me along the way towards completing this dissertation. -

CSG Journal 31

Book Reviews 2016-2017 - ‘Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements’ In the LUP book, several key sites appear in various chapters, such as those on siege warfare and castles, some of which have also been discussed recently in academic journals. For example, a paper by Duncan Wright and others on Burwell in Cambridgeshire, famous for its Geoffrey de Mandeville association, has ap- peared in Landscape History for 2016, the writ- ers also being responsible for another paper, this on Cam’s Hill, near Malmesbury, Wilt- shire, that appeared in that county’s archaeolog- ical journal for 2015. Burwell and Cam’s Hill are but two of twelve sites that were targeted as part of the Lever- hulme project. The other sites are: Castle Carl- ton (Lincolnshire); ‘The Rings’, below Corfe (Dorset); Crowmarsh by Wallingford (Oxford- shire); Folly Hill, Faringdon (Oxfordshire); Hailes Camp (Gloucestershire); Hamstead Mar- shall, Castle I (Berkshire); Mountsorrel Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements: (Leicestershire); Giant’s Hill, Rampton (Cam- Surveying the Archaeology of the bridgeshire); Wellow (Nottinghamshire); and Twelfth Century Church End, Woodwalton (Cambridgeshire). Edited by Duncan W. Wright and Oliver H. The book begins with a brief introduction on Creighton surveying the archaeology of the twelfth centu- Publisher: Archaeopress Publishing ry in England, and ends with a conclusion and Publication date: 2016 suggestions for further research, such as on Paperback: xi, 167 pages battlefield archaeology, largely omitted (delib- Illustrations: 146 figures, 9 tables erately) from the project. A site that is recom- ISBN: 978-1-78491-476-9 mended in particular is that of the battle of the Price: £45 Standard, near Northallerton in North York- shire, an engagement fought successfully This is a companion volume to Creighton and against the invading Scots in 1138. -

Two Discs from Fores's Moving Panorama. Phenakistiscope Discs

Frames per second / Pre-cinema, Cinema, Video / Illustrated catalogue at www.paperbooks.ca/26 01 Fores, Samuel William Two discs from Fores’s moving panorama. London: S. W. Fores, 41 Piccadily, 1833. Two separate discs; with vibrantly-coloured lithographic images on circular card-stock (with diameters of 23 cm.). Both discs featuring two-tier narratives; the first, with festive subject of music and drinking/dancing (with 10 images and 10 apertures), the second featuring a chap in Tam o' shanter, jumping over a ball and performing a jig (with 12 images and 12 apertures). £ 350 each (w/ modern facsimile handle available for additional £ 120) Being some of the earliest pre-cinema devices—most often attributed either to either Joseph Plateau of Belgium or the Austrian Stampfer, circa 1832—phenakistiscopes (sometimes called fantascopes) functioned as indirect media, requiring a mirror through which to view the rotating discs, with the discrete illustrations activated into a singular animation through the interruption-pattern produced by the set of punched apertures. The early discs offered here were issued from the Piccadily premises of Samuel William Fores (1761-1838)—not long after Ackermann first introduced the format into London. Fores had already become prolific in the publishing and marketing of caricatures, and was here trying to leverage his expertise for the newest form of popular entertainment, with his Fores’s moving panorama. 02 Anonymous Phenakistiscope discs. [Germany?], circa 1840s. Four engraved card discs (diameters avg. 18 -

Some Famous Missourians

JOSEPHINE BAKER OMAR N. BRADLEY (Born 1906; died 1975) (Born 1893; died 1981) Born in the Mill Creek Bottom area of St. Bradley, born near Clark, commanded the Louis, Baker’s childhood resembled that of largest American force ever united under one thousands of other black Americans who lived man’s leadership. Known as “the G.I.’s gen- in poverty and dealt with white America’s eral” during World War II, Bradley became racist attitudes. In France, however, where the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff racism was not as rampant, Baker became after the war. As a five-star general, Bradley an international presence well known for served 69 years on active duty—longer than her provocative productions. Her reputation, any other soldier in U.S. history. built on a 50-year career as a dancer, singer, and actress, allowed Baker to devote much of her life to fighting racial prejudice in the United States. She played an active role in Missouri State Archives the American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s. THOMAS HART BENTON GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER (Born 1889; died 1975) (Born 1864; died 1943) Born in Neosho, Benton was destined to Born a slave near Diamond, Carver over- become a renowned artist. Two of his best- came tremendous obstacles to become one of known works appear in mural form at the America’s greatest scientists. He is best re- State Capitol in Jefferson City and the Tru- membered for his practical research, helping man Library in In de pen dence. The Capitol farmers make a better living from marginal mural is a pan orama of Missouri history; soil. -

I Wonder. . . I Notice

I notice. P a c i f i c O c e a n Gulf of CANADA St. Lawrence Washington Delaware Montana and Hudson Oregon Lake Canal North Dakota Minnesota Superior Maine Yellowstone Idaho NP Vermont Lake Huron New Hampshire Wisconsin rio Wyoming South Dakota Onta Lake Massachusetts New York Great Salt Lake Michigan Nevada Lake Michigan ie Er ke Rhode Nebraska Iowa La Island Utah M Pennsylvania Yosemite NP i s Connecticut s o Ohio u Colorado r New Jersey i R Illinois Indiana iv r Washington D.C. e er Delaware iv Kansas R West io California h Missouri O Virginia Virginia Maryland Grand Canyon NP Kentucky Arizona North Carolina Oklahoma Tennessee New r Arkansas e v i R Mexico i South p p i Carolina s s i s s i Georgia M Alabama Union States Texas Mississippi Confederate States Louisiana A t l a n t i c Border states that O c e a n stayed in the Union Florida Other states G u l f MEXICO National Parks o f Delaware and M e x i c o Hudson Canal, 1866 John Wesley Jarvis (1780–1840) Philip Hone, 1809 Oil on wood panel, 34 x 26¾ in. (86.4 x 67.9 cm) Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd 1986.84 I wonder. 19th-Century American Object Information Sheet 8th Grade 1 Philip Hone Lakes to the Hudson River. This new 19TH-CENTURY AMERICA waterway greatly decreased the cost of shipping. IETY C O S Politically, Hone was influential AL Your Historic Compass: C in the organization of the Whig Whig party: The Whig party first took shape in 1834.