Research Issues1 Wybrane Zespoły Bramne Na Śląsku

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

CSG Journal 31

Book Reviews 2016-2017 - ‘Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements’ In the LUP book, several key sites appear in various chapters, such as those on siege warfare and castles, some of which have also been discussed recently in academic journals. For example, a paper by Duncan Wright and others on Burwell in Cambridgeshire, famous for its Geoffrey de Mandeville association, has ap- peared in Landscape History for 2016, the writ- ers also being responsible for another paper, this on Cam’s Hill, near Malmesbury, Wilt- shire, that appeared in that county’s archaeolog- ical journal for 2015. Burwell and Cam’s Hill are but two of twelve sites that were targeted as part of the Lever- hulme project. The other sites are: Castle Carl- ton (Lincolnshire); ‘The Rings’, below Corfe (Dorset); Crowmarsh by Wallingford (Oxford- shire); Folly Hill, Faringdon (Oxfordshire); Hailes Camp (Gloucestershire); Hamstead Mar- shall, Castle I (Berkshire); Mountsorrel Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements: (Leicestershire); Giant’s Hill, Rampton (Cam- Surveying the Archaeology of the bridgeshire); Wellow (Nottinghamshire); and Twelfth Century Church End, Woodwalton (Cambridgeshire). Edited by Duncan W. Wright and Oliver H. The book begins with a brief introduction on Creighton surveying the archaeology of the twelfth centu- Publisher: Archaeopress Publishing ry in England, and ends with a conclusion and Publication date: 2016 suggestions for further research, such as on Paperback: xi, 167 pages battlefield archaeology, largely omitted (delib- Illustrations: 146 figures, 9 tables erately) from the project. A site that is recom- ISBN: 978-1-78491-476-9 mended in particular is that of the battle of the Price: £45 Standard, near Northallerton in North York- shire, an engagement fought successfully This is a companion volume to Creighton and against the invading Scots in 1138. -

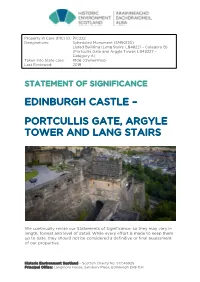

Edinburgh Castle (Portcullis Gate, Argyle Tower & Lang Stairs) Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC222 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90130) Listed Building (Lang Stairs: LB48221 – Category B) (Portcullis Gate and Argyle Tower: LB48227 – Category A) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last Reviewed: 2019 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE EDINBURGH CASTLE – PORTCULLIS GATE, ARGYLE TOWER AND LANG STAIRS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: -

The Portcullis Revised August 2010

Factsheet G9 House of Commons Information Office General Series The Portcullis Revised August 2010 Contents Introduction 2 Other uses for the Portcullis 2 Charles Barry and the New Palace 3 Modern uses 4 This factsheet has been archived so the content City of Westminster 4 and web links may be out of date. Please visit Westminster fire office 4 our About Parliament pages for current Other users 5 information. Styles 5 Appendix A 7 Examples of uses of the Portcullis 7 Further reading 8 Contact information 8 Feedback form 9 The crowned portcullis has come to be accepted during the twentieth century as the emblem of both Houses of Parliament. As with many aspects of parliamentary life, this has arisen through custom and usage rather than as a result of any conscious decision. This factsheet describes the history and use of the Portcullis. August 2010 FS G 09 Ed 3.5 ISSN 0144-4689 © Parliamentary Copyright (House of Commons) 2009 May be reproduced for purposes of private study or research without permission. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes not permitted. 2 The Portcullis House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G9 Introduction Since 1967, the crowned portcullis has been used exclusively on House of Commons stationery. It replaced an oval device, which had been in use since the turn of the twentieth century, on the recommendation of the Select Committee on House of Commons (Services). The portcullis probably came to be associated with the Palace of Westminster through its use, along with Tudor roses, fleurs-de-lys and pomegranates, as decoration in the rebuilding of the Palace after the fire of 1512. -

Citadel of the Severed Hand - by Rob S a Fallen Dwarf Citadel

Citadel of the Severed Hand - by Rob S A fallen dwarf citadel. Ground level is a solid barbican and tower. First level belongs to the Severed hand tribe of orcs, most are away at war. If citadel observed, PCs see orc take waste buckets to fungus caves. Peryton flies off hunting. When dark faint glow from fungus caves. 1. Tangled woods - 5 half orcs with a log ram wait in the woods; know the Severed hand tribe are away. Will raid citadel tonight. Big Grin: friendly, greedy and fat; the leader. Potential allies. 2. Barbican and gate - muddy slope leads to gates. Nailed to gate are many rotting hands. Keeping watch on battlements are 3 orcs; short bows; horn fixed to battlement. 3. Peryton tower - Peryton and young at top of tower. Ally of orcs who feed them. If combat at barbican Peryton will arrive in 3 rounds. Blackened, gutted tower filled with bones. Rusted shut trapdoor concealed by rocks; access to fungus caverns. 4. Ancestors Hall - Ruined grandeur. High vaulted ceilings. Defaced stone carvings tell of Kiel who tamed the Perytons and ruled over the area with his unique cavalry. Covered in crude orc graffiti/scratchings. 4 orcs. Lever lowers a portcullis sealing off stairs. Stairs down if you want to expand adventure. 5. Barracks - tribal living area appears recently vacated. 6 orcs remain; planning shroom raid. 2 scratched and gouged tables. Patched up chairs and stools. Sleeping furs, skins and rags. Access to fungus caves concealed beneath barrel. 6. Boss room - Blud: brooding and practical; orcs boss. He wears the Staghelm. -

Drawbridge, Portcullis, Battlements, Moat, Gatehouse, Curtain Wall, Tower, Arrow Slits

Otter Class 8.6.20 Hello Otter Class! I hope you have had a nice week. I can’t believe it is June already! We have a brand new topic..Castles! Here are some ideas to start you off on our new topic! 1) Make a list of everything you know about castles. What were theyfor? Who lived in castles? Do you know the names of any famous castles? 2) Write some questions. What do you want to find out about castles? Remember all your special question words (who/why/when etc) and don’t forget your question mark... 3) Word challenge...what do these words mean? Drawbridge, portcullis, battlements, moat, gatehouse, curtain wall, tower, arrow slits... You could look in a book or search on the internet. You could write a definition for each word (what it means) to make a castle word glossary (a tricky word list) You could even draw a picture to go with each word or print one out. You might discover some other castle words too! 4) Design your own castle and draw a picture. Label it with some of the words from above. What is your castle called? Who lives in it? You could even make a model of your castle. You could use recycled materials or Lego or think of a different way to make your model. These castles might give you some ideas when you design your own! 1) Reading ideas Remember to keep on reading! It could be a story or non fiction book about minibeast or anything you like! You could do some cooking with your grown up and help read the recipe/instructions. -

Glossary of Terms

www.nysmm.org Glossary of Terms Some definitions have links to images. ABATIS: Barricade of felled trees with their branches towards the attack and sharpened (primitive version of "barbed wire"). ARROW SLITS: Narrow openings in a wall through which defenders can fire arrows. (also called loopholes) ARTILLERY: An excellent GLOSSARY for Civil War era (and other) Artillery terminologies can be found at civilwarartillery.com/main.htm (Link will open new window.) BAILEY: The walled enclosure or the outer courtyard of a castle. (Ward, Parade) BANQUETTE: The step of earth within the parapet, sufficiently high to enable standing defenders to fire over the crest of the parapet with ease. BARBICAN: Outworks, especially in front of a gate. A heavily fortified gate or tower. BARTIZAN (BARTISAN): Scottish term, projecting corner turret. A small overhanging turret on a tower s battlement. BASTION: A projection from a fortification arranged to give a wider range of fire or to allow firing along the main walls. Usually at the intersection of two walls. BATTER: Inclined face of a wall (Talus). BATTERED: May be used to describe crenellations. BATTERY: A section of guns, a named part of the main fortifications or a separate outer works position (e.g.. North Battery, Water Battery). BATTLEMENTS: The notched top (crenellated parapet) of a defensive wall, with open spaces (crenels) for firing weapons. BEAKED PROJECTION: see EN BEC. BELVEDERE: A pavilion or raised turret. BLOCKHOUSE: Usually a two story wood building with an overhanging second floor and rifle loops and could also have cannon ports (embrasures). Some three story versions. Some with corner projections similar to bastions. -

The Impact Off Crusader Castles Upon European Western Castles

THE IMPACT OF CRUSADER CASTLES UPON EUROPEAN WESTERN CASTLES IN THE MIDDLE AGES JORDAN HAMPE MAY 2009 A SENIOR PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- LA CROSSE Abstract: During the Middle Ages, the period from roughly AD 1000-1450, the structure of castles changed greatly from wooden motte and bailey to stone keeps and defenses within stone city walls. The reason for the change was largely influenced by the crusades as Europeans went to the Holy Lands to conquer. In addition to conquering, these kings brought back a new way of designing and fortifying their castles in England, Wales and France. Without the influence of the crusades, what we think of as true middle age castles would not exist. For my paper I will analyze the impact the crusades had on forming the middle age castles by evidence surviving in the archaeological record from before and after the crusades as well as modifications done on castles to accommodate crusader changes to show the drastic influence of crusader castle fortifications upon English, Welsh and French castles. 1 Introduction Construction of what is believed to be true middle age castles from A.D. 1000 to 1450 began as kings arrived back from the crusades to the Holy Lands, bringing with them ideas of how to make their castles grander and more easily defensible. Before the crusades William I of England was beginning to develop a new concentric style of castle beginning with the Tower of London. After the crusades many English, Welsh and French kings took the concentric concept and combined it with what they saw on the crusades and developed it to become majestic castles and fortresses like Chateau Gaillard in France, Dover Castle in England, and Caernarvon Castle in Wales. -

Castles and Cathedrals

Castles and Cathedrals Proudly supported by the Tri-Border Girl Scouts Folklore and fairytales, Princes, Knights, and Kings are storybook characters to most of us. But as we begin living overseas and visiting some Castles and Cathedrals we begin to learn fact from fiction. Castles Castles were homes that were also fortresses. Many were built during the Middle Ages. During that time wars were fought and land defended by powerful individuals rather than by central governments. These residences were intended for a King, Lord, or Nobleman. Thick walls and high battlements were known as early as the days of the Assyrians (8th century BC). Weapons and embroidered tapestries decorated stone walls and animal skins covered the floors. Cathedrals It’s been said that Cathedrals are Christianity’s most glorious contribution to the art of building. In Medieval days, all of Western Europe was Roman Catholic. Entire communities united in an effort to build a church to bring credit to the city as well as to glorify God. Different styles of architecture Byzantine: Combines styles that come from the Middle East and from Ancient Rome Romanesque: Northern art began to influence Roman art and a new style was born Gothic: 12th Century, Cathedrals had an upward thrust as though reaching for Heaven Challenges for all Girls 1. Visit at least 3 (total) Castles & Cathedrals. Please list them and where they are located. A. B. C. 2. Draw a picture of one of the Castles or Cathedrals that you visited. 3. What kind of architecture was predominately used in the design of the Castle or Cathedral you drew? 4. -

A-Walk-In-Our-Shoes

2 3 4 Canterbury One of the most historic of English cities, Canterbury is famous for its medieval cathedral. There was a settlement here before the Roman invasion, but it was the arrival of St Augustine in 597 AD that was the signal for Canterbury's growth. Augustine built a cathedral within the city walls, and a new monastery outside the walls. The ruins of St Augustine's Abbey can still be seen today. Initially the abbey was more important than the cathedral, but the murder of St Thomas a Becket in 1170 changed all that. Pilgrims flocked to Canterbury to visit the shrine of the murdered archbishop, and Canterbury Cathedral became the richest in the land. It was expanded and rebuilt to become one of the finest examples of medieval architecture in Britain. But there is more to Canterbury than the cathedral. The 12th century Eastbridge Hospital was a guesthouse for pilgrims, and features medieval wall paintings and a Pilgrim's Chapel. The old West Gate of the city walls still survives, and the keep of a 11th century castle. St Dunstan's church holds a rather gruesome relic; the head of Sir Thomas More, executed by Henry VIII. The area around the cathedral is a maze of twisting medieval streets and alleys, full of historic buildings. Taken as a whole, Canterbury is one of the most satisfying historic cities to visit in England. 5 St Augustine's Abbey In this case the abbey isn't just dedicated to St. Augustine, it was actually founded by him, in 598, to house the monks he brought with him to convert the Britons to Christianity. -

The West Gate of Winchester

HANTS FIELD CLUB AND ARCH/EOLOGICAL SOCIETY, 1898 PLATE I. WEST GATE, WINCHESTER, FROM A DRAW.™ BY S. PROUT. 1810. 51 THE WEST GATE OF WINCHESTER. BY W. H. JACOB. The West Gate, which forms a handsome termination to the picturesque High Street, Winchester, is the only one left of the gates of the Royal city, save that called Kihgsgate, which .has been saved from destruction by the little church of St. Swithun resting on its arches. For many years the interior has been an unknown place, to visitors it was a for- bidden sight, and but few people have ever seen it; From the middle of the 18th century, its ancient .features have been hidden by whitewash, lath and plaster, deal cupboards, and shelves. For some years in this century it was used as a muniment room, where also was stored an enormous mass of waste paper of the late Victorian age. This vast accumu- lation Mr. Stopher and the writer were allowed to examine. Having made selection of valuable matter, the rubbish was relegated to a paper mill, after which a couple of years were spent in an inquisition of a great variety of ancient records, the result being a fine collection of court records, chamber- lain's arid hospital rolls, coffer, ordinance, and other books, ranging over several centuries. This labour, added to pre- vious efforts of Mr. F. J. Baigent, leaves but little more to do beyond the provision of a fit receptacle for the collection. Before proceeding to speak of West Gate, its history in the.past and present condition, we would allude to the accusation against the Pavement Commissioners made by Dr. -

Chepstow Castle

Chepstow Castle Information for education group leaders Chepstow Castle is one of many built to secure the border with Wales and took advantage of a naturally defended position. Its substantial defences and domestic buildings provide clear evidence of the various roles of castles in the medieval period and how they were adapted for later use and occupation. A visit will support the development of historical skills and enquiry at all Key Stages. History The twin-towered gatehouse The castle was established by William fitz Osbern, a loyal guarding the entrance to supporter of William the Conqueror. The great tower was the castle. the first stone structure built, incorporating masonry from the nearby Roman town at Caerwent. In 1189 the castle passed to William Marshal who used his knowledge of advanced castle technology in the Holy Land to fortify Chepstow. Each of his five sons inherited and they continued to improve the castle. On the death of the last son, the castle passed to the Bigod family. In 1270 Roger Bigod II converted the castle into a palatial stronghold, building an extensive range of buildings in the lower bailey. In 1507, Charles Somerset became lord of Chepstow. A favourite of Henry VII and Henry VIII, he built a suite of apartments on either side of the wall dividing the lower and middle baileys. He also improved other buildings, adding new, larger windows and fireplaces. In the Civil War, the castle was twice taken by Parliamentarians. Afterwards, its fortifications were repaired and modified to take cannon, and gun loops were added for musket fire.