Reviews: Ed Mcknight Fiction Reviews: Philip Snyder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rediscovery of Man Free Download

THE REDISCOVERY OF MAN FREE DOWNLOAD Cordwainer Smith | 400 pages | 29 Mar 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575094246 | English | London, United Kingdom The Rediscovery of Man Sure, I can say it has pages of acclaimed stories—every short story that Cordwainer Smith ever wrote. After defeat, after disappointment, after ruin and reconstruction, mankind had leapt among the stars. The Rediscovery of Man Rediscovery of Man, by Cordwainer Smith. The majority of these stories take place 14, yeas into the future, and The Rediscovery of Man this day, present a The Rediscovery of Man worldview, and an astounding examination of human nature. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. This brilliant collection, often cited as the first of its kind, explores fundamental questions about ourselves and our treatment of the universe and other beings around us and ultimately what it means to be human. Cordwainer Smith is a writer like none other. These stories were written in the late 50s, early 60s, and are so intelligent and forward thinking, I'm still stunned. Underpeople do all the hard work, police is made up of robots and telepathic mind control checks that everybody is thinking happy thoughts, or they are sent for re-education. A Cordwainer Smith Panel Discussion. That said, when I said last time that I was relieved that Tiptree's radical feminism never crossed the line into open transphobia, a finger on the monkey's paw curled up and delivered me Smith's "The Tranny Menace from Beyond the Stars" "The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal," about which I have absolutely nothing positive to say. -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

Dec. 2006 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE

PO Box 656, Washington, DC 20044 - (202) 232-3141 - Issue #201 - Dec. 2006 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.lambdasf.org/ New Year’s Eve Reminder: Annual LSF Dec. 2006 - Feb. 2007 Video Party Book Exchange Battlestar Galactica Parties announced by Set for Jan. 14th Meeting from Peter Knapp Peter Knapp Come celebrate New Year’s Eve (and other with Lambda Sci-Fi at Rob and Peter’s stuff, too!) home in DC. This annual event will give us a chance to both recover from the That’s right, gang, the Holiday hectic “holiday” season and to party Season is almost upon us again; and it’s some more in anticipation of the new time for a short reminder about Lambda year. Here are the details on how to join Sci-Fi’s upcoming seventeenth annual in on the fun! book (et al) exchange, which will occur at Where: The home of Rob & the January 14th meeting! All LSF mem- Rob and I will be hosting par- Peter - 1425 “S” Street, NW Washington, bers are invited to participate in this “blind ties to view the next four episodes of DC. For directions, see: exchange” -- and visitors are invited to Battlestar Galactica and Jonathan will http://www.lambdasf.org/lsf/club/ join in the fun, too! be the host for the following four epi- PeterRob.html Briefly, this will be an opportu- sodes. Because the holiday season is Date: Sunday, Dec. 31, 2006 nity for LSFers to exchange copies of their upon us, the Sci Fi Channel will be not be Time: The doors will open at favorite science-fiction, fantasy, or hor- broadcasting the show some weekends. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree on April 26, 2009, the James Tiptree, Jr

Spring/Summer 2009 Volume 5 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree On April 26, 2009, The James Tiptree, Jr. H New Essay Collection from Literary Award Council announced that the Ursula K. Le Guin 2008 Tiptree Award will be going to Patrick Special Features Ness’s young adult novel The Knife of Never Letting Go and Nisi Shawl’s Filter House, an H Hanging out along the Aqueduct…, by Nisi Shawl Aqueduct Press book. page 9 The Tiptree Award, an annual literary prize H L. Timmel Duchamp for science fiction or fantasy “that expands or Interviews Liz Henry about explores our understanding of gender,” will The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 3 be presented on Memorial Day weekend at page 6 WisCon in Madison, Wisconsin. Each winner H Gwyneth Jones writes about will receive $1000 in prize money, an original The Buonarotti Quartet artwork created specifically for the winning page 2 novel or story, and a confection, usually choco- H Three Observations and a late. The 2008 jurors were Gavin J. Grant Dialogue by Sylvia Kelso page 2 (chair), K. Tempest Bradford, Leslie Howle, Roz Kaveney, and Catherynne M. Valente. In Other News The award is named for Alice B. Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym H Aqueduct Celebrates James Tiptree, Jr. By her impulsive choice of a masculine pen name, Sheldon 5th Anniversary cont. on page 5 page 8 H New Spring Releases New from Aqueduct: Ursula K. Le Guin, page 12 Cheek by Jowl Talks and Essays about How and Why Fantasy Matters The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

Cosmopolitanism, Remediation and the Ghost World of Bollywood

COSMOPOLITANISM, REMEDIATION, AND THE GHOST WORLD OF BOLLYWOOD DAVID NOVAK CUniversity ofA California, Santa Barbara Over the past two decades, there has been unprecedented interest in Asian popular media in the United States. Regionally identified productions such as Japanese anime, Hong Kong action movies, and Bollywood film have developed substantial nondiasporic fan bases in North America and Europe. This transnational consumption has passed largely under the radar of culturalist interpretations, to be described as an ephemeral by-product of media circulation and its eclectic overproduction of images and signifiers. But culture is produced anew in these “foreign takes” on popular media, in which acts of cultural borrowing channel emergent forms of cosmopolitan subjectivity. Bollywood’s global circulations have been especially complex and surprising in reaching beyond South Asian diasporas to connect with audiences throughout the world. But unlike markets in Africa, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia, the growing North American reception of Bollywood is not necessarily based on the films themselves but on excerpts from classic Bollywood films, especially song-and- dance sequences. The music is redistributed on Western-produced compilations andsampledonDJremixCDssuchasBollywood Beats, Bollywood Breaks, and Bollywood Funk; costumes and choreography are parodied on mainstream television programs; “Bollywood dancing” is all over YouTube and classes are offered both in India and the United States.1 In this essay, I trace the circulation of Jaan Pehechaan Ho, a song-and-dance sequence from the 1965 Raja Nawathe film Gumnaam that has been widely recircu- lated in an “alternative” nondiasporic reception in the United States. I begin with CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 25, Issue 1, pp. -

UX and Agile: a Bollywood Blockbuster Masala

UX and Agile: A Bollywood blockbuster masala Pradeep Joseph UXD Manager Juniper Networks Bangalore What is Bollywood? Wikipedia says: The name "Bollywood" is derived from Bombay (the former name for Mumbai) and Hollywood, the center of the American film industry. However, unlike Hollywood, Bollywood does not exist as a physical place. Bollywood films are mostly musicals, and are expected to contain catchy music in the form of song-and-dance numbers woven into the script. Indian audiences expect full value for their money. Songs and dances, love triangles, comedy and dare-devil thrills are all mixed up in a three-hour- long extravaganza with an intermission. Such movies are called masala films, after the Hindi word for a spice mixture. Like masalas, these movies are a mixture of many things such as action, comedy, romance and so on. Melodrama and romance are common ingredients to Bollywood films. They frequently employ formulaic ingredients such as star-crossed lovers and angry parents, love triangles, family ties, sacrifice, corrupt politicians, kidnappers, conniving villains, courtesans with hearts of gold, long-lost relatives and siblings separated by fate, dramatic reversals of fortune, and convenient coincidences. What has UX and Agile got to do with Bollywood? As a Designer I faced tremendous challenges while moving into an Agile environment. While drowning the sorrows with designers from other organizations I came to realize that they too face similar challenges. This inspired me to explore further into what makes designers sad, what makes them suck and what are the ways in which they can contribute more in an Agile environment. -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

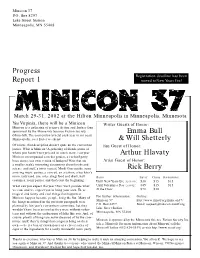

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

The Ninth Science Fiction Megapack Is Copyright © 2014 by Wildside Press LLC

Contents COPYRIGHT INFO . 3 A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER . 6 . THE MEGAPACK SERIES . 9 INTERVIEW: DAN SIMMONS, conducted by Darrell Schweitzer . 16 . THE SPIRES OF DENON, by Kristine Kathryn Rusch . 30 AIN’T NOTHIN’ BUT A HOUND DOG, by Brenda W . Clough . 128 FOR I AM A JEALOUS PEOPLE! by Lester del Rey . .139 . LUVVER, by Mack Reynolds . 187 FROG LEVEL, by Bud Webster . 202 CAPTAINS CONSPIRING AT THEIR MUTINIES, by Jay Lake . 224 . SHIFTING SEAS, by Stanley G . Weinbaum . 264 . THROUGH TIME AND SPACESample WITH FERDINAND file FEGHOOT: 8, by Grendel Briarton . 290 ROCK GARDEN, by Kevin O’Donnell, Jr . 291 THE GENOA PASSAGE, by George Zebrowski . 308 . EIGHT O’CLOCK IN THE MORNING, by Ray Faraday Nelson . 321. I AM TOMORROW, by Lester del Rey . 327 WHEN THEY COME FROM SPACE, by Mark Clifton . 370. THE SEALED SKY, by Cynthia Ward . 532. METEOR STRIKE! by Donald E . Westlake . .538 . WAITING FOR THE COIN TO DROP, by Dean Wesley Smith . 575 . Contents | 2 BEYOND THE DARKNESS, by S . J . Byrne . 587 THE SMALLEST GOD, by Lester del Rey . 670 THE SCIENCE FICTION ALPHABET, by Allen Glasser . 710 . CANAL, by Carl Jacobi . .713 . THE LOCH MOOSE MONSTER, by Janet Kagan . 729 MY FAIR PLANET, by Evelyn E . Smith . 763. BEFORE EDEN, by Arthur C . Clarke . 780 SEQUENCE, by Carl Jacobi . 793 PREFERRED RISK, by Frederik Pohl and Lester del Rey . 800 . INTEVIEW: FREDERIK POHL, conducted by Darrell Schweitzer . 969 . ABOUT THE AUTHORS . 979 Sample file Contents | 3 COPYRIGHT INFO The Ninth Science Fiction Megapack is copyright © 2014 by Wildside Press LLC . -

Steam Engine Time 5

Steam Engine T ime PRIEST’S ‘THE SEPARATION’ MEMOS FROM NORSTRILIA CENSORSHIP IN AUSTRALIA POLITICS AND SF Harry Hennessey Buerkett James Doig Paul Kincaid Gillian Polack Eric S. Raymond Milan Smiljkovic Janine Stinson Issue 5 September 2006 Steam Engine T ime 5 STEAM ENGINE TIME No. 5, September 2006 is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia ([email protected]) and Janine Stinson, PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248, USA ([email protected]). Members fwa. First edition is in .PDF file format from eFanzines.com or from either of our email addresses. Print edition available for The Usual (letters or substantial emails of comment, artistic contributions, articles, reviews, traded publications or review copies) or subscriptions (Australia: $40 for 5, cheques to ‘Gillespie & Cochrane Pty Ltd’; Overseas: $US30 or £15 for 5, or equivalent, airmail; please send folding money, not cheques). Printed by Copy Place, 415 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000. The print edition is made possible by a generous financial donation. Graphics Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front cover). Photographs Covers of various books and magazines discussed in this issue; plus photos of (p. 5) Christopher Priest, by Ian Maule; (p. 24) Roger Dard, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 25) Roger Dard fanzine contributions, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 32) Nigel Burwood, Martin Stone and Bill Blackbeard, by John Baxter; (p. 39) David Boutland. 3 EDITORIAL 1: 32 Letters of comment ‘Dream your dreams’: A meditation on Babylon 5 John Baxter Janine Stinson Rosaleen Love Steve Jeffery 4 EDITORIAL 2 E. B. Frohvet Bruce Gillespie Steve Sneyd Sydney J.