Making Governance Work Is a Series of Essays from University, Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Final Report Ncsciencefestival.Org 3 the Nation’S First Statewide >> Event Map & Highlights Science Festival

the nation’s first statewide science festival proudly produced by final 2010report the nation’s first statewide >> letter to our supporters >> festival highlights science festival December 2010 Dear friends, 85,860 16 The authors James Collins and Jerry Porras introduced the concept of the strategic, emotionally-compelling Big Hairy Audacious total attendance at NC days in first NC Science Goal (“BHAG”), defining a true BHAG as a goal that is “clear and compelling, serves as a unifying focal point, and acts as a Science Festival events Festival (Sept. 11–26, 2010) clear catalyst for team spirit.” The idea of creating the nation’s first statewide science festival was truly a BHAG when the idea started to take shape in late 2009. But from Orville and Wilbur’s first flight to our basketball teams, North Carolina takes pride in being first. And as we introduced the idea of the North Carolina Science Festival, North Carolina responded enthusiastically. From elementary school students to transnational corporations, we found partners and supporters around every corner and an 413 174 appetite for science that heartened us. individual events unique events First, our state’s business community immediately saw (including repeat sessions) the Festival’s value and provided sponsorship dollars that helped us deliver a high-quality program of events. Without our sponsors, we would not have been able to present the Festival. All of our sponsors are very important to us, but 78 111 we think that the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, SAS and Time unique events Warner Cable & News 14 Carolina deserve special recognition program partners for having the faith in our vision to become Platinum Sponsors in the Piedmont in the very first year. -

Facilities Inventory and Utilization Study 2010

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA HIGHER EDUCATION COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING PROGRAM FACILITIES INVENTORY AND UTILIZATION STUDY 2010 School of Pharmacy, Elizabeth City State University HIGHER EDUCATION COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING PROGRAM FACILITIES INVENTORY AND UTILIZATION STUDY FALL OF 2010 For THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA FORTY-FOURTH EDITION THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA Facilities Space Utilization and Analysis Chapel Hill, North Carolina September 2011 School of Pharmacy Complex Elizabeth City State University (Cover Page) Starting in fall 2010, pharmacy students at the Elizabeth City site began taking their classes in a new 52,500 square foot building located at the west entrance to the ECSU campus. This $21.9 million, three story facility, whose architecture was inspired by the idea of an apothecary chest, overlooks an artificial pond and contains classrooms and labs organized around a two-story atrium. The first floor contains general science labs, a library, and a drug information center, while the second floor houses the IV simulation lab and the compounding lab. The third floor features three research labs for biochemistry, molecular biology, and medicinal chemistry, as well as a computer lab. Other classrooms, meeting rooms, and offices are distributed throughout the building to create a more collaborative environment for students, faculty, and staff. In the last decade, 45 of North Carolina’s 100 counties did not increase their supply of pharmacists rapidly enough to keep pace with population growth. Due to a need for more pharmacists in eastern North Carolina, the General Assembly allocated funds in 2004 for a new pharmacy program at Elizabeth City State University to be taught in conjunction with faculty located at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

H. Holden Thorp Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Kenan Professor of Chemistry Chancellor-Elect Address

H. Holden Thorp Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Kenan Professor of Chemistry Chancellor-Elect Address: College of Arts and Sciences University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3100 (919)962-3082 Academic Positions: Department of Chemistry, North Carolina State University: Assistant Professor (January 1991 - June 1993). Department of Chemistry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Visiting Assistant Professor (January - June 1993), Assistant Professor (July 1993 - December 1995), Associate Professor (January 1996 – June 1999), Vice-Chair for Undergraduate Studies (July 1995 – June 2000), Member of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (January 1997 - present), Professor (July 1999 – June 2005); Kenan Professor (July 2005 – present); Department Chair (July 2005 – May 2007); Faculty Director of Fundraising, Carolina Physical Science Complex (2003 – 2007). Morehead Planetarium and Science Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Director (August 2001 – June 2005). College of Arts and Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Dean (July 2007 – June 2008). Chancellor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: (beginning July 2008) Education: Post-doctoral: Yale University (July 1989 - December 1990) Advisor: Gary W. Brudvig Graduate: California Institute of Technology (1986 - 1989) Ph.D. Chemistry - June 1989 Graduate research advisor: Harry B. Gray Undergraduate: University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill (1982 - 1986) B.S. Chemistry - May 1986 Undergraduate research advisor: Thomas J. Meyer Fellowships and Honors: London Scientific Lecturer (Simon Fraser University – 2006), Kenan Professorship (2004), UNC General Alumni Association Distinguished Young Alumnus (2002), Honorary Member of the Order of the Golden Fleece (2002), Fortune Small Business Top Innovators of 2001, CED Life Science Technology of the Year (2000), NAS Frontiers of Science Participant (1999), Tanner Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching (1998), Ruth and Philip Hettleman Prize for Artistic and Scholarly Achievement (1996), Alfred P. -

New Center to Shed Light on Impact of Natural Disasters

UNIVERSITY Vol. 33, No. 15 gazette.unc.edu September 10, 2008 Carolina Faculty and Staff News New center to 2 REGISTER YOUR CELL PHONE shed light on impact of natural disasters 6 CHAPEL CREEK Rick Luettich is internationally recognized for his work in storm surge and coastal modeling. RESTORATION ith four named tropical storms threatening U.S. coastlines recognized for his work in storm surge and other coastal modeling, within two weeks, the launch of Carolina’s new Center is director of the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences and professor of for the Study of Natural Hazards and Disasters is timely. marine sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences. He also serves WChancellor Holden Thorp discussed the University's plans to create the RENCI as chief domain scientist in coastal modeling. RENCI will center at a celebratory event last week. collaborate with center researchers to provide visualization and compu- Housed within the center will be a new Center of Excellence for tational resources. the Study of Natural Disasters, Coastal Infrastructure and Emergency With more than 50 percent of the nation’s population living along Management. Funded with a multimillion dollar grant from the U.S. the coasts, the knowledge generated by the center will have an immedi- Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Center of Excellence ate, significant impact, Thorp said. will study natural disasters in coastal areas. The research it conducts “It is a way we can connect the depth of the research we are already 7 BILLY will provide emergency managers with the latest scientific information doing with the real problems our nation is facing,” he said. -

2009 UNC Soccer Media Guide Table of Contents Carolina Quick Facts 2009 Senior Class

Carolina Women’s Soccer • General Information 2009 UNC Soccer Media Guide Table of Contents Carolina Quick Facts 2009 Senior Class .............................FrontCover Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. Celebrating UNC’s 2008 NCAA Championship . .Inside Front Cover Established: December 11, 1789 Table of Contents, Quick Facts, Credits, Website Info, Nike Info . .1 Enrollment: 28,136 (17,895 undergraduate, 8,275 postgraduates) 2009 Roster ...........................................2 Chancellor: Dr. Holden Thorp 2009 Schedule ........................................3 Director of Athletics: Dick Baddour 2009 Outlook ..........................................4 Senior Women’s Administrator: Beth Miller WinForeverFund......................................7 National Affiliation: NCAA Division I 2008 National Championship Season Review ................8 Conference: Atlantic Coast Conference 2009 Player Biographies ................................12 Nickname: Tar Heels Head Coach Anson Dorrance ............................36 Mascot: Rameses the Ram (both live and costumed) Chief Assistant Coach Bill Palladino .......................40 School Colors: Carolina Blue and White Assistant Coach Chris Ducar ............................41 Athletic Department Website: www.TarHeelBlue.com Carolina Women’s Soccer Staff ..........................42 Carolina Women’s Soccer Information Carolina Women’s Soccer History ........................43 Head Coach: Anson Dorrance (North Carolina, ‘74) Tar Heel Historical Honor Roll of Awards ...................50 Record -

Chapel Hill Officials and Leaders of Ram Development Company Work Together to Break Ground on the 140 West Franklin Multi-Use Development at a Jan

Serving UNC students and the University community since 1893 The Daily Tar Heel VoLumE 118, ISSuE 128 monday, january 10, 2011 www.dailytarheel.com a nEw forcE on frankLIn DTH/VICTORIA STILWELL Chapel Hill officials and leaders of Ram Development Company work together to break ground on the 140 West Franklin multi-use development at a Jan. 5 ceremony. The new complex is slated to be completed in late 2012. 140 west aims to revitalize downtown area BY VICTORIA STIlwell downtown atmosphere. The structure will stand eight sto- CITY EDITOR ries tall at its highest point and contain 140 units of upscale On the hunt for a condominium, Bill Spiegel first condominiums, 28,540 square feet of ground-level retail heard about the 140 West Franklin development more space and 337 private and public parking spaces. than two years ago from an unlikely source: a salesman The complex is a half-mile from the Greenbridge for Greenbridge, the new Rosemary Street development mixed-use development, which finished construction just blocks away. in October, and is just 2 miles from East 54, a self-pro- “He mentioned two other condominium projects,” claimed “urban village” of luxury condominiums, shop- said Spiegel, a 1971 UNC graduate and former asthma ping and dining. researcher. “The one that was the least far along was 140 Mike Hammon, the chief development officer for Ram West Franklin. Being downtown really appealed to me — Realty Services, said 140 West’s location sets it apart from and the fact that it wasn’t happening very soon.” the other complexes. -

GOVERNING Magazine June 2012

THE STATES AND LOCALITIES June 2012 $4.50 Southern Suburban &Black The shifting demographics of African- Americans are reshaping cities across the South. Alicia Newburn recently moved from the Midwest to the Dallas area. GOV06_Cover1.indd 1 5/16/12 9:11 AM 100 Blue Ravine Road Designer Creative Dir. Folsom, CA 95630 916-932-1300 Editorial Prepress $ZBO .BHFOUB :FMMPX #MBDL m PAGE Other OK to go VOL. 25, NO. 9 06.2012 FEATURES 24 THE NEW BLACK SOUTH In Dallas and other cities across the South, African-Americans are reshaping suburban neighborhoods. By Alan Greenblatt 32 PASS/FAIL The greatest public universities in America are at a tipping point. By Peter A. Harkness 40 DOES THE MANDATE MATTER? Can universal health care work without an individual mandate? Ask the states that have been answering that question for 20 years. Dennis Webb is By John Buntin the senior pastor at Bear Creek 46 WELCOME TO WALMART Community Big cities learn to love the big box. Baptist Church By Ryan Holeywell in Irving, Texas, and serves on the Dallas City 52 ON-STREET PARKING Council. Parklets are the next big tiny idea in urban planning. By Zach Patton PHOTO BY DAVID KIDD COVER PHOTO BY DAVID KIDD June 2012 | GOVERNING 1 GOV06_01 new version.indd 1 5/15/12 10:47 AM 100 Blue Ravine Road Designer Creative Dir. Folsom, CA 95630 916-932-1300 Editorial Prepress $ZBO .BHFOUB :FMMPX #MBDL m PAGE Other OK to go DEPARTMENTS 4 Publisher’s Desk 6 Letters OBSERVER 9 A Right to Resist An Indiana law says citizens can use deadly force against a cop. -

Chapel Hill 2020 Comprehensive Plan

Chapel Hill 2020 Comprehensive Plan Report 2: Process and Outreach Summary Adopted: June 25, 2012 Cover art by Sarah Mitchell, winner of Chapel Hill 2020 Art Contest, grade 10-12 category. Table of Contents Chapter 1: Overview of the Process............................................................1 Chapter 2: Outreach Efforts ........................................................................9 Chapter 3: Community Input .....................................................................17 CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW OF THE PROCEss CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW OF THE PROCESS “Everyone needs goals and a philosophy of life — and that goes for towns and cities, too. Without these, we carom blindly from decision to decision, without any consensus on whom or what we want to be.” —Michael Collins, Planning Board Member Initiation of the New Comprehensive Plan – A Different Approach In order to set a course for the future and not to “carom blindly from decision to decision,” the Chapel Hill Mayor and Town Council established the development of a new comprehensive plan as the community’s preeminent goal for 2011-2012. The Town Council began by appointing an Initiating Committee which was comprised of community members who represented a diversity of backgrounds and viewpoints. The Initiating Committee designed a process for creating the new comprehensive plan that underlined the importance of broadly including all community members in the visioning and decision-making process. To provide leadership for the development of the new comprehensive plan, the Initiating Committee determined that two co-chairs were needed. George Cianciolo and Rosemary Waldorf accepted this charge and worked enthusiastically, overseeing the process. They stayed true to the inclusionary goals of the Initiating Committee and encouraged all participants to create a plan that would be truly useful to the Mayor, Town Council, Town staff, and the community. -

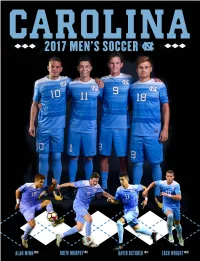

2017MSOC Yearbookweb.Pdf

Supporting Carolina Men’s Soccer UNC Athletic Communications Table Of Contents The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Men’s Soccer Contact: Mark Kimmel General Information 1 Nike, Inc. signed a 10-year contract for Nike to be the Email Address: [email protected] exclusive supplier of athletic footwear, apparel and acces- Office Phone: (919) 962-0084 2017 Schedule 2 sory products to the Tar Heels effective July 1, 2008. Nike Cell Phone: (919) 619-3344 2017 Roster 3 will provide the athletic department with shoes, uniforms, Mailing address: P.O. Box 2126 coaching gear, balls and other equipment. In addition to Chapel Hill, NC 27515 Player Profiles 4-13 the apparel and equipment, which constitutes the majority Head Coach Carlos Somoano 14-15 of the value of the contract, Nike will give the University $2 Please contact Mark Kimmel for information on covering the million to the Chancellor’s Academic Enhancement Fund. UNC men’s soccer team. Assistant Coaches 15-16 Chancellor Holden Thorp says he will direct the funds to Support Staff 17 faculty support. Nike will also provide support for team University Quick Facts tours, travel and hosting regular-season tournaments in Athletic Administration 17 Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. several sports. The athletic department will also receive $1 Chartered: 1789 Fetzer Field 18 million for signing the contract, with those funds being used Enrollment: 18,523 to overhaul lighting and sound at the Dean E. Smith Center. McCaskill Soccer Center 19 Chancellor: Carol L. Folt Director of Athletics: Bubba Cunningham This Is Carolina Soccer 20-25 2017 Men’s Soccer Yearbook Affiliation: NCAA Division I 2016 Stats and Season Review 26-31 The 2017 North Carolina men’s soccer yearbook was Conference: Atlantic Coast Conference designed and edited by Mark Kimmel, Assistant Director Nickname: Tar Heels A History of Tar Heel Soccer 32-33 of Athletic Communications, with assistance from the UNC Mascot: Rameses (a ram) NCAA Championships 34-35 Athletic Communications staff. -

Annual Report 2012–2013

Annual Report 2012–2013 Dear Members of the General Assembly, On behalf of the Committee – and on behalf of North Carolina’s cancer in return. UCRF has leveraged record amounts of research funding from patients and their loved ones, both current and future – thank you for your outside North Carolina, has increased the number of research patents and ongoing support of the University Cancer Research Fund and the research discoveries, and has produced results that have helped create new jobs it fuels. The economic and health benefits of this landmark investment have and spinoff companies. More than 140 outstanding cancer researchers have been significant and will continue to have an impact for years to come. been retained or hired with UCRF support. Although prevention, diagnostic, and treatment tools are improving, As you likely know, my successor, Carol Folt, takes office as Chancellor on cancer remains our state’s deadliest disease and the No. 2 cause of death July 1, and I am excited about the leadership she will bring to the University. nationwide. It is crucial to continue supporting and conducting research that As Chair of the Cancer Research Fund Committee, I have been honored to will rein in and eventually cure this disease. The University Cancer Research play a role in overseeing this landmark investment by the General Assembly Fund has been a critical investment in the fight against cancer, and as a and the State in the health of North Carolinians. I am proud to share this scientist I have been inspired by the difference our students and faculty are annual report with each of you. -

Innovation @ Carolina

Innovation @ Carolina Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Te University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Background and Sample of Current Activities A Working Report Version 1.0, December 22, 2009 Authors: Maryann Feldman, Judith Cone, Mark Meares, Lowry Caudill, Jennifer Miller, Lauren Lanahan, and Gil Avnimelech P REPARED FOR THE INNOVAT I O N CIRCL E CON V ENED B Y CHANCELLOR HOLDEN THO RP, JANUARY 2010 Membership as of December 23, 2009 University of Utah TractManager Salt Lake City, Utah Saddle Brook, New Jersey The Chancellor’s Innovation Circle Jason Kilar CEO, Hulu LLC Christy Shaffer Seattle, Washington CEO, Inspire Rye Barcott Dennis Gillings Pharmaceuticals Founder, Carolina Chairman, CEO, Richard Krasno Chapel Hill, North Carolina for Kibera Quintiles Transnational Executive Director, Charlotte, North Carolina Corporation William R. Kenan, Jr. Sallie Shuping-Russell Durham, North Carolina Charitable Trust; Managing Director, Harris Scott Barton Trustee, Kenan Institute Blackrock Alternative Managing Director, Julia Sprunt Grumbles of Private Enterprise Advisors Capital Dynamics Vice President, Turner Chapel Hill, North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina Palo Alto, California Broadcasting (Retired) Chapel Hill, North Carolina Myla Lai-Goldman M.D. Richard Stack Vaughn Bryson Scientific Advisor, Director, Founder, President, CEO Reginald Lee Seventh Sense President, Synecor LLC Eli Lilly & Co. (Retired) (Reg) Hardy Biosystems, Inc. Chapel Hill, North Carolina President, Managing Director, Cambridge, Massachusetts Clinical Products, Ltd. C/Max Capital Corporation William (Bill) N. Starling Vero Beach, Florida Fort Lauderdale, Florida Doug Mackenzie Managing Director, Founder, Partner, Radar; Synergy Life Science W. Lowry Caudill F. Neal Hunter Affiliated Partner at Partners; CEO, Synecor LLC Chair, Co-founder, Co-Founder, Executive Kleiner, Perkins, Portola Valley, California Magellan Laboratories, Chair, Cree, Inc. -

Mental Health Care in North Carolina

School of Social Work The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Contact Fall 2008 Mental Health Care in North Carolina Advocating for care and the challenges ahead establish a professorship focused in the area of poverty. Also in September, the School unveiled its new Web site. It was created completely to train its social workers. We are currently in-house, by staff members Manuel Garcia, From the Dean... planning our next summer study abroad trips Michelle Rogers, John Anderson and Susan to South Africa and China. White, with input provided by faculty, staff In August, we welcomed three new assis- and students. his issue of Contact spotlights the criti- tant professors to our faculty—Gina Chowa, In October, UNC-Chapel Hill installed cal issue of mental health care reform Gary Cuddeback and Joan Yoo. a new chancellor, Holden Thorp. He shows a in North Carolina, the challenges Gina Chowa is the principal investigator great understanding of social work and I look Tahead, and the many ways we are advocating for AssetsAfrica, a research demonstration forward to working with him. for better care. Here are some highlights. project in Sub-Saharan Africa. AssetsAfrica, Several of our faculty have received grants Our faculty are actively engaged in in- now in its 5th year, is a quasi-experimental, for their projects recently, many of which are novative research that examines programs, matched savings project in Masindi, a rural detailed in the Faculty Spotlight section on policies and services geared toward improving district in Uganda. Her future research will pages 16-17. the state’s public mental health and addiction draw on lessons learned from the Uganda Unfortunately, along with the good there care system.