Juan Sebastián Elcano in Spanish 'Notaphily': Two Views, One Feat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WW2-Spain-Tripbook.Pdf

SPAIN 1 Page Spanish Civil War (clockwise from top-left) • Members of the XI International Brigade at the Battle of Belchite • Bf 109 with Nationalist markings • Bombing of an airfield in Spanish West Africa • Republican soldiers at the Siege of the Alcázar • Nationalist soldiers operating an anti-aircraft gun • HMS Royal Oakin an incursion around Gibraltar Date 17 July 1936 – 1 April 1939 (2 years, 8 months, 2 weeks and 1 day) Location Spain Result Nationalist victory • End of the Second Spanish Republic • Establishment of the Spanish State under the rule of Francisco Franco Belligerents 2 Page Republicans Nationalists • Ejército Popular • FET y de las JONS[b] • Popular Front • FE de las JONS[c] • CNT-FAI • Requetés[c] • UGT • CEDA[c] • Generalitat de Catalunya • Renovación Española[c] • Euzko Gudarostea[a] • Army of Africa • International Brigades • Italy • Supported by: • Germany • Soviet Union • Supported by: • Mexico • Portugal • France (1936) • Vatican City (Diplomatic) • Foreign volunteers • Foreign volunteers Commanders and leaders Republican leaders Nationalist leaders • Manuel Azaña • José Sanjurjo † • Julián Besteiro • Emilio Mola † • Francisco Largo Caballero • Francisco Franco • Juan Negrín • Gonzalo Queipo de Llano • Indalecio Prieto • Juan Yagüe • Vicente Rojo Lluch • Miguel Cabanellas † • José Miaja • Fidel Dávila Arrondo • Juan Modesto • Manuel Goded Llopis † • Juan Hernández Saravia • Manuel Hedilla • Carlos Romero Giménez • Manuel Fal Conde • Buenaventura Durruti † • Lluís Companys • José Antonio Aguirre Strength 1936 -

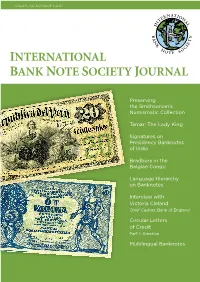

IBNS Journal Volume 56 Issue 1

VOLUME 56, NUMBER 1, 2017 INTERNATIONAL BANK NOTE SOCIETY JOURNAL Preserving the Smithsonian’s Numismatic Collection Tamar: The Lady King Signatures on Presidency Banknotes of India Bradbury in the Belgian Congo Language Hierarchy on Banknotes Interview with Victoria Cleland Chief Cashier, Bank of England Circular Letters of Credit Part 1: America Multilingual Banknotes President’s Message Table of inter in North Dakota is such a great time of year to stay indoors and work Contents on banknotes. Outside we have months of freezing temperatures with Wmany subzero days and brutal windchills down to – 50°. Did you know that – 40° is the only identical temperature on both the Fahrenheit and Centigrade President’s Message.......................... 1 scales? Add several feet of snow piled even higher after plows open the roads and From the Editor ................................ 3 you’ll understand why the early January FUN Show in Florida is such a welcome way to begin the New Year and reaffirm the popularity of numismatics. IBNS Hall of Fame ........................... 3 This year’s FUN Show had nearly 1500 dealers. Although most are focused on U.S. Obituary ............................................ 5 paper money and coins, there were large crowds and ever more world paper money. It was fun (no pun intended) to see so many IBNS members, including several overseas Banknote News ................................ 7 guests, and to visit representatives from many auction companies. Besides the major Preserving the Smithsonian’s numismatic shows each year, there are a plethora of local shows almost everywhere Numismatic Collection’s with occasional good finds and great stories to be found. International Banknotes The increasing cost of collecting banknotes is among everyone’s top priority. -

Latin Derivatives Dictionary

Dedication: 3/15/05 I dedicate this collection to my friends Orville and Evelyn Brynelson and my parents George and Marion Greenwald. I especially thank James Steckel, Barbara Zbikowski, Gustavo Betancourt, and Joshua Ellis, colleagues and computer experts extraordinaire, for their invaluable assistance. Kathy Hart, MUHS librarian, was most helpful in suggesting sources. I further thank Gaylan DuBose, Ed Long, Hugh Himwich, Susan Schearer, Gardy Warren, and Kaye Warren for their encouragement and advice. My former students and now Classics professors Daniel Curley and Anthony Hollingsworth also deserve mention for their advice, assistance, and friendship. My student Michael Kocorowski encouraged and provoked me into beginning this dictionary. Certamen players Michael Fleisch, James Ruel, Jeff Tudor, and Ryan Thom were inspirations. Sue Smith provided advice. James Radtke, James Beaudoin, Richard Hallberg, Sylvester Kreilein, and James Wilkinson assisted with words from modern foreign languages. Without the advice of these and many others this dictionary could not have been compiled. Lastly I thank all my colleagues and students at Marquette University High School who have made my teaching career a joy. Basic sources: American College Dictionary (ACD) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (AHD) Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) Oxford English Dictionary (OCD) Webster’s International Dictionary (eds. 2, 3) (W2, W3) Liddell and Scott (LS) Lewis and Short (LS) Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD) Schaffer: Greek Derivative Dictionary, Latin Derivative Dictionary In addition many other sources were consulted; numerous etymology texts and readers were helpful. Zeno’s Word Frequency guide assisted in determining the relative importance of words. However, all judgments (and errors) are finally mine. -

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University 206 Book Reviews

http://englishkyoto-seas.org/ <Book Review> Ken MacLean Allison J. Truitt. Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013, xii+193p. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, April 2015, pp. 206-209. How to Cite: MacLean, Ken. Review of Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City by Allison J. Truitt. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, April 2015, pp. 206-209. Link to this article: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/2015/04/vol-4-no-1-book-reviews-ken-maclean/ View the table of contents for this issue: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/2015/04/vol-4-1-of-southeast-asian-studies Subscriptions: http://englishkyoto-seas.org/mailing-list/ For permissions, please send an e-mail to: [email protected] Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University 206 Book Reviews People. New Delhi: Hindustan Pub. Corp. Wang, Zhusheng. 1997. The Jingpo: Kachin of the Yunnan Plateau. Tempe, AZ: Program for Southeast Asian Studies. Wyatt, David K. 1997. Southeast Asia ‘Inside Out,’ 1300–1800: A Perspective from the Interior. Modern Asian Studies 31(3): 689–709. Dreaming of Money in Ho Chi Minh City ALLISON J. TRUITT Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013, xii+193p. The scholarly study of banknotes (notaphily) is not a new phenomenon. But it did not take sys- tematic modern form until the 1920s. (Ironically, it emerged under the Weimar Republic just as Germany was entering a three-year period of hyperinflation.) Since then, the number of numis- matic associations has grown considerably, as have specialized publications. -

March Rahul.Cdr

Editor : Siddharth N.S Co - Editor : Tejas Shah Sr. 3rd Year 34th Issue March 2018 Pages 12 22 62231833 e-mail - [email protected] Special Cover in Delhi National Museum 9th National Numismatic Rare Stamps on Women memory of Upendra Pai in need of a Numismatist Exhibition Bangaluru Achievers in Mangaluru Government Pays Two Times for Duplicate Sikh Coins Though Originals Available at Half Price hen the collection of original Sikh coins is available at half the price in the open market, the Punjab WGovernment has paid lakhs of rupees to a private firm just for minting duplicate coins. These coins will be placed at the upcoming Sikh Coins Museum at Gobindgarh Fort.For building interiors of the museum, the then SAD-BJP government had given a contract for Rs 5.5 crore to a Delhi-based firm. The contract also included Rs. 20 lakh for supplying duplicates of around 400 coins related to the Sikh history. The decision has raised eyebrows. According to numismatics, most of the original Sikh coins in copper are available anywhere between Rs. 150 and Rs. 200 and silver coins between Rs. 1,500 and Rs. 2,500. Cont on Page 4th ..... Collecting 'Fake Coins' – The Unknown Facet of Coin Collecting n the world of coin collecting, we are believed to stay away from the 'Fake' & 'Counterfeit' coins. Begetting any of these unknowingly Ileaves us in a state of dismay. Novelty coins, replica coins, copy coins… No matter what term we may use, those are fake coins! Coins that aren't 100 percent mint made has grown up into a huge collection for Mr. -

Stamp News Canadian

www.canadianstampnews.ca An essential resource for the CANADIAN advanced and beginning collector Like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/canadianstampnews Follow us on Twitter @trajanpublisher STAMP NEWS Follow us on Instagram @trajan_csn Volume 44 • Number 24 March 17 - 30, 2020 $5.50 ‘Thanks for the Smokes’ Long-time reveals soldiers’ popular solace Unitrade By Jesse Robitaille Freedom to Smoke: Tobacco Con- Now considered a deadly sumption and Identity, and the habit killing nearly 40,000 Cana- main channel of proliferation editor has dians a year, smoking was was the mail. widely popular in decades past, The troops” “special including during the world need” was the cigarette, wrote deep hobby wars, when Canada’s annual Iain Gately in his 2001 book, La cigarette consumption exceeded Diva Nicotina: The Story of How two billion for the first time. Tobacco Seduced the World. The First World War “legiti- “Their slightest wish should roots mized the cigarette,” according be gratified, and in 18 out of 20 By Jesse Robitaille to Jarrett Rudy’s 2005 book, The Continued on page 38 This is the first story in a multi- part series exploring the recent history of the Unitrade Special- ized Catalogue of Canadian Stamps. n avid collector of modern Canadian stamps and pur- veyorA of all things philatelic, Robin Harris was seemingly Unitrade catalogue editor Robin Harris, of Manitoba, has made for the role of editor of been an active collector since the late 1960s. Unitrade’s long-running stamp catalogue. Published annually for more Harris, who added the previous 2005. A month later, it received a than two decades, the Unitrade editor was an employee of To- gold medal at Canada’s Seventh Specialized Catalogue of Canadian ronto’s Unitrade Associates National Philatelic Literature Ex- Stamps owes much of its evolu- who “wasn’t involved with hibition, which was held in con- tion to long-time editor Robin stamps.” junction with that year’s Harris, of Manitoba, who started There were dozens of updates Stampex in Toronto. -

Madrid, Spain's Capital

Madrid, Spain’s Capital Maribel’s Guide to Madrid © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ May 2020 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 Index Madrid’s Neighborhoods - Page 3 • Mercado de San Antón Getting Around - Page 8 • Mercado de San Miguel • From Madrid-Barajas to the city center • Mercado de Antón Martín • City Transportation • Mercado de Barceló Madrid Sites - Page 13 • Mercado de San Ildefonso El Huerto de Lucas • Sights that can be visited on Monday • Gourmet Experience Gran Vía • What’s Free and When • Gourmet Experience Serrano • Sights that children enjoy • 17th-century Hapsburg Madrid - Page 15 Flea Markets - Page 46 Mercado del Rastro • Plaza Mayor • Mercado de los Motores • Palacio Real de Madrid • Mercado de las Ranas (Frogs Market) • Changing of the Royal Guard • • Cuesta de Moyano Beyond Old Madrid - Page 20 • Plaza Monumental de las Ventas Guided Tours - Page 47 Hop on Hop off Bus • Santiago Bernabéu soccer stadium • • Madrid-Museum-Tours Madrid’s Golden Art Triangle - Page 22 • Madrid Cool and Cultural • Museo del Prado • San Jerónimo el Real Food & Wine Tours - Page 49 Gourmet Madrid • Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza • Madrid Tours and Tastings • Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía • • Adventurous Appetites Noteworthy Exhibition Spaces - Page 29 • Madrid Tapas Trip • Caixa Forum - Madrid • Walks of Madrid Tapas Tour • Royal Botanical Gardens • Fundacíon Mapfre Sala Recoletos Cooking Classes - Page 51 • Cooking Point Worthwhile Small Museums - Page 31 • Soy Chef (I’m a Chef) • Museo Sorolla -

The Malaspina Expedition (1789-1794) in Republican Chile

Historia. vol.1 no.se Santiago 2006 THE NATIONAL INFLUENCE OF AN IMPERIAL ENTERPRISE: THE MALASPINA EXPEDITION (1789-1794) IN REPUBLICAN CHILE ANDRÉS ESTEFANE JARAMILLO* Abstract The research done by members of the Malaspina Expedition (1789-1794) during their stay in Chile was not only useful in that same period, but also in post- colonial era. In 19th century, republican authorities had to recur to the information recompiled by the scientific expeditions of the Illustration – and especially that of Malaspina – to complete the lack of up to date information in geographical matters, to solve territorial disputes with neighboring countries and to start new explorations aimed to know the exact characteristics of regions recently joined to national sovereignty. The continuing recovery of the expeditions` registers create a new link between the last century of colonial domination and the first century of our republican history, a moment in which science would play a main role in the recuperation and reinterpretation of the meaning of geographical knowledge from the previous century. During the 19th century, the nations of Latin America made a continuous effort to recover the research done by several scientific expeditions that arrived to America during the last century of colonial domination. The lack of up to date information and the need for details about the characteristics and economic potentials of those territories, aroused in republican authorities the interest to recover any information from the past that might be useful to the needs of the new political reality. The dazzling sense of urgency with which ethnographic observations, botanical and zoological notes, essays on mineralogy, iconography and surveys on cartography were recompiled, confirm the intensity with which this task was undertaken; not only investigating in local archives, but also financing recurrent visits to libraries and collections of documents in Europe. -

MANAGEMENT in the FUNCTION of ENLARGEMENT of the ISSUING PROFIT Prof

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Management in the Function of Enlargement of the Issuing Profit Matić, Branko J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Economics 2005 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10857/ MPRA Paper No. 10857, posted 01 Oct 2008 08:47 UTC MANAGEMENT IN THE FUNCTION OF ENLARGEMENT OF ... 115 MANAGEMENT IN THE FUNCTION OF ENLARGEMENT OF THE ISSUING PROFIT Prof. Dr. Branko Mati} Faculty of Economics in Osijek Summary The author starts from the thesis that it is especially necessary to manage the production of cash money, taking into consideration and applying the conceptions of modern management. Cash money (metallic and paper) is a specific “product” that is produced according to the needs of monetary traffic, as well as meeting the standards related to modern notaphily, i.e. numismatics. For several reasons, the author elaborates his thesis on the example of the issuing of Croatian contemporary metallic money. The most important of these reasons are that Croatia has its own mint, that issuing metallic money makes it possible to attain significant non-fiscal effects through its management, and that the issuing of national money has wider cultural, social, legal and other dimensions. In the elaboration of his thesis, the author takes into account the influence of the globalization and integration proces- ses in which Croatia is a participant. Key words: management, innovation, issuing profit, money, exchange rate, Euroland 1. Introduction The notion of contemporary Croatian monetary system is connected with the establishment of the sovereignty of the Republic of Croatia. After declaring its inde- pendence (on 30th May 1990) on 23rd December 1991 Croatia introduced its tran- sitional, temporary monetary unit - the Croatian Dinar. -

Page 13 « IBSS AGM NEWS Tennessee Copper « BOOK REVIEWS « on the ROAD? Dutch Plantations in the East Indies – Page 17

SCRIPOPHILYTHE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL BOND & SHARE SOCIETY ENCOURAGING COLLECTING SINCE 1978 No.94 - APRIL 2014 Just Deserts Rare Comstock – page 10 Belgian Investments The high price of in Romania – page 20 – page 13 « IBSS AGM NEWS Tennessee Copper « BOOK REVIEWS « ON THE ROAD? Dutch plantations in the East Indies – page 17 Scripophily Top 100 Worldwide Auction News The newest centurion at $35,700 – page 23 – page 6 Interesting Reaching specimens at out to a National Show billion users THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL BOND & SHARE SOCIETY SCRIPOPHILY ENCOURAGING COLLECTING SINCE 1978 INTERNATIONAL BOND & SHARE SOCIETY APRIL 2014 • ISSUE 94 CHAIRMAN - Andreas Reineke Alemannenweg 10, D-63128 Dietzenbach, Germany. Tel: (+49) 6074 33747. Email: [email protected] SOCIETY MATTERS 2 DEPUTY CHAIRMAN - Mario Boone NEWS AND REVIEWS 5 Kouter 126, B-9800 Deinze, Belgium. Tel: (+32) 9 386 90 91 Fax: (+32) 9 386 97 66. Email: [email protected] • World Top 100 • Wells Fargo Mining Co SECRETARY & MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY - Philip Atkinson 167 Barnett Wood Lane, Ashtead, Surrey, KT21 2LP, UK. • IBSS AGM • Book Reviews Tel: (+44) 1372 276787. Email: [email protected] • National Show .... and more besides TREASURER - Martyn Probyn Flat 2, 19 Nevern Square, London, SW5 9PD, UK COX’S CORNER 11 T/F: (+44) 20 7373 3556. Email: [email protected] AUCTIONEER - Bruce Castlo FEATURES 1 Little Pipers Close, Goffs Oak, Herts EN7 5LH, UK. Tel: (+44) 1707 875659. Email: [email protected] On the Road? Visit a Fellow Scripophilist! 12 MARKETING - Martin Zanke by Max Hensley Glasgower Str. 27, 13349 Berlin, Germany. 13 Tel: (+49) 30 6170 9995. -

El Propósito De Este Artículo Es Doble

NOTAS Y DOCUMENTOS SOBRE LA PROTECCIÓN Y EVACUACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO DOCUMENTAL Y BIBLIOGRÁFICO DURANTE LA GUERRA CIVIL ESPAÑOLA ENRIQUE PÉREZ BOYERO. JEFE DEL ARCHIVO. BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL DE ESPAÑA [Enrique Pérez Boyero, «Notas y documentos sobre la protección y evacuación del patrimonio documental y bibliográfico durante la Guerra Civil Española», Manuscrt.Cao, 9, ISSN: 1136-3703] Resumen: Este artículo ofrece información sobre la protección y evacuación del patrimonio documental y bibliográfico en la España republicana durante la Guerra Civil. En los apéndices se incluyen, entre otros, un catálogo de documentos que permiten identificar cada uno de los volúmenes manuscritos e impresos que fueron evacuados a Valencia y Ginebra procedentes de la Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, de la Biblioteca Nacional de España y de algunas bibliotecas particulares que habían sido incautadas y depositadas en esta última (bibliotecas de Lázaro Galdiano, del duque de T’Serclaes, del marqués de Toca y del duque de Medinaceli). Abstract: This article offers information about the protection and evacuation of the documental and bibliographical patrimony in Republican Spain during the Civil War. Catalogues that allow us to identify which manuscripts and printed books were evacuated to Valencia and Ginebra are included in the appendixes. The concerned volumes came primarily from the Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial and from the Biblioteca Nacional de España. Included in the collections of the latter appear volumes coming from some private libraries that had been previously confiscated, such as Lázaro Galdiano, the one belonged to the duke of T’Serclaes, the one belonged to the Marquis of Toca or the one owned by the duke of Medinaceli. -

The Best of Madrid Madrid

05_047286 ch01.qxp 12/14/06 9:30 PM Page 4 1 The Best of Madrid Madrid is on a roll. Never a city to let the grass grow under its feet, the Spanish capi- tal is experiencing unprecedented change thanks to the efforts of the visionary mayor Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón—a man compared by some, however tongue in cheek, to a pharaoh. In 2005 the mayor launched a new 7-year city program aimed at transform- ing the capital into a world-class cosmopolitan center, with improved Metro and rail transport and the expansion of new barrios, or districts, especially in the north of the city where a tren ligero (a smaller, streamlined Talgo-shaped tram similar to those suc- cessfully operating in Bilbao) is scheduled to be in operation by spring 2007. Though the completion of all this work was originally timed to coincide with Madrid’s expected nomination as venue for the 2012 Olympics, the city’s disbelief at being beaten for the honor by London was quickly forgotten (maudlin introspection is not part of the feisty Madrileño temperament). In fact, many completion schedules have been brought forward to coincide with the municipal elections of May 2007. Two new terminals at Barajas airport were inaugurated in February 2006, more than doubling the city’s international traffic and making the airport the third busiest in Europe, while Chamartín railway station is being totally rebuilt to merge with a renovated Metro station and a new underground regional and long-distance bus ter- minal. Each of the four skyscrapers currently under construction (Torres Repsol, Espa- cio, Sacyr, and Cristal) will outstrip Torre Picasso in the AZCA Business Center as the highest building in town; at the same time, pedestrian and subway underpasses are being tunneled and countless streets and avenues widened, all aimed at improving road access.