SRI: Coastal Resource Management Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Biogeography of Mangroves in Sri Lanka

Ceylon Journal of Science 46 (Special Issue) 2017: 119-125 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/cjs.v46i5.7459 RESEARCH ARTICLE Ecological biogeography of mangroves in Sri Lanka M.D. Amarasinghe1,* and K.A.R.S. Perera2 1Department of Botany, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya 2Department of Botany, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Nugegoda Received: 10/01/2017; Accepted: 10/08/2017 Abstract: The relatively low extent of mangroves in Sri extensively the observations are made and how reliable the Lanka supports 23 true mangrove plant species. In the last few identification of plants is, thus, rendering a considerable decades, more plant species that naturally occur in terrestrial and element of subjectivity. An attempt to reduce subjectivity freshwater habitats are observed in mangrove areas in Sri Lanka. in this respect is presented in the paper on “Historical Increasing freshwater input to estuaries and lagoons through biogeography of mangroves in Sri Lanka” in this volume. upstream irrigation works and altered rainfall regimes appear to have changed their species composition and distribution. This MATERIALS AND METHODS will alter the vegetation structure, processes and functions of Literature on mangrove distribution in Sri Lanka was mangrove ecosystems in Sri Lanka. The geographical distribution collated to analyze the gaps in knowledge on distribution/ of mangrove plant taxa in the micro-tidal coastal areas of Sri occurrence of true mangrove species. Recently published Lanka is investigated to have an insight into the climatic and information on mangrove distribution on the northern anthropogenic factors that can potentially influence the ecological and eastern coasts could not be found, most probably for biogeography of mangroves and sustainability of these mangrove the reason that these areas were inaccessible until the ecosystems. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

Sri Lanka for the Clean Energy and Access Improvement Project

Sustainable Power Sector Support Project (RRP SRI 39415) Detailed Description of Project Components A. Transmission system strengthening 1. This component will contribute to a reliable, adequate and affordable power supply for sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction in Eastern, North Central, Southern and Uva provinces. The strengthened transmission system will alleviate existing sub- standard voltage conditions in Ampara district of the Eastern Province and provide increased load capacity in the Eastern, North Central, Southern and Uva provinces leading to improved efficiency and reliability in power supply. The component includes the following sub-projects: (i) New Galle Power Transmission Development: Construction of New Galle 3 x 31.5 megavolt ampere (MVA) 132/33 kilovolt (kV) grid substation and Ambalangoda-to- New Galle 40 kilometers (km) double circuit 132 kV transmission line: T1a: New 3 x 31.5 MVA 132/33 kV New Galle Grid Substation Construction of a new grid substation at Galle comprising: 132 kV double busbar switchyard with: o 4 feeder bays o 1 static VAR compensator bay +10 megavolt ampere reactive (MVAr) to - 20 MVAr for voltage support o 3 transformer bays o 1 bus-coupler bay o 3 x 31.5 MVA transformers 33 kV switchyard with: o 3 transformer bays o 2 bus-section bays o 10 feeder bays o 2 generator bays o 6 capacitor bays with total of 30 MVA capacitors for loss reduction Control room and all associated communications, protection and control. This substation is located adjacent to the existing Galle 132/33 kV substation, which is old and cannot be extended further. -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

Registered Suppliers and Contractors for the Year- 2021 District Secretariat-Galle

Registered Suppliers And Contractors 2021 2 District Secretariat - Galle Content Subject Page No. Stationery and office requisites (Computer Papers, Roneo Papers, CD, Printer Toner, Printer Ribbon, Photocopy 01. 01 Cartridge including Fax Roll) ..…………….............……………………………………………………………….……… Office Equipments (Printers, Photocopy Machines, Roneo Machines, Digital Duplo Machines, Fax Machines) 02. 04 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….………….. 03. Office Furniture (Wooden, Steel and Plastic) …………………………………….......................................................... 06 04. Computers and Computer Accessories and Networking Devices ……………………….……………………….…………… 08 05. Domestic Electrical Equipment (Televisions,Sewing Machines,Refrigerators,Washing Machines etc.) ……..… 10 06. Generators ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………… 12 07. Rubber Stamps ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………… 13 08. Textile Materials for doors and windows,bed clothes,uniforms ………………………………………………..………….. 14 09. Beauty Culture Equipments ….…...……………………………………………………………………………………………..…………… 15 10. Office Bags ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………. 16 11. School Equipments (Bags,Shoes, etc..) ……………………………………………………………………………………….…………… 17 12. Sports Goods and Body Building Equipment ……………………………………………………………………………….……………... 18 13. Musical Instruments …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………….. 19 14. Tyres,Tubes, and Batteries for vehicles …………………………………………………………………………………………….……….. 20 15. Vehicle Spare Parts ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………… -

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 7

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 7 Sri Lanka International Religious Freedom Report 2008 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The Constitution accords Buddhism the "foremost place" and commits the Government to protecting it, but does not recognize it as the state religion. The Constitution also provides for the right of members of other religious groups to freely practice their religious beliefs. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the period covered by this report. While the Government publicly endorses religious freedom, in practice, there were problems in some areas. There were sporadic attacks on Christian churches by Buddhist extremists and some societal tension due to ongoing allegations of forced conversions. There were also attacks on Muslims in the Eastern Province by progovernment Tamil militias; these appear to be due to ethnic and political tensions rather than the Muslim community's religious beliefs. The U.S. Government discusses religious freedom with the Government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. U.S. Embassy officials conveyed U.S. Government concerns about church attacks to government leaders and urged them to arrest and prosecute the perpetrators. U.S. Embassy officials also expressed concern to the Government about the negative impact anticonversion laws could have on religious freedom. The U.S. Government continued to discuss general religious freedom concerns with religious leaders. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 25,322 square miles and a population of 20.1 million. Approximately 70 percent of the population is Buddhist, 15 percent Hindu, 8 percent Christian, and 7 percent Muslim. -

Evaluation of Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector in Sri Lanka

Evaluation Working Paper Sri Lanka Country Assistance Program Evaluation: Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Assistance Evaluation August 2007 Supplementary Appendix A Operations Evaluation Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 August 2007) Currency Unit — Sri Lanka rupee (SLR) SLR1.00 = $0.0089 $1.00 = SLR111.78 ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank GDP — gross domestic product ha — hectare kg — kilogram TA — technical assistance UNDP — United Nations Development Programme NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Director General Bruce Murray, Operations Evaluation Department (OED) Director R. Keith Leonard, Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Evaluation Team Leader Njoman Bestari, Principal Evaluation Specialist Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Operations Evaluation Department CONTENTS Page Maps ii A. Scope and Purpose 1 B. Sector Context 1 C. The Country Sector Strategy and Program of ADB 11 1. ADB’s Sector Strategies in the Country 11 2. ADB’s Sector Assistance Program 15 D. Assessment of ADB’s Sector Strategy and Assistance Program 19 E. ADB’s Performance in the Sector 27 F. Identified Lessons 28 1. Major Lessons 28 2. Other Lessons 29 G. Future Challenges and Opportunities 30 Appendix Positioning of ADB’s Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Strategies in Sri Lanka 33 Njoman Bestari (team leader, principal evaluation specialist), Alvin C. Morales (evaluation officer), and Brenda Katon (consultant, evaluation research associate) prepared this evaluation working paper. Caren Joy Mongcopa (senior operations evaluation assistant) provided administrative and research assistance to the evaluation team. The guidelines formally adopted by the Operations Evaluation Department (OED) on avoiding conflict of interest in its independent evaluations were observed in the preparation of this report. -

Fisheries and Environmental Profile of Chilaw Estuary

REGIONAL FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA (RFLP) --------------------------------------------------------- Fisheries and environmental profile of Chilaw lagoon: a literature review (Activity 1.3.1 Prepare fisheries and environmental profile of Chilaw lagoon using secondary data and survey reports) For the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia Prepared by Leslie Joseph Co-management consultant June 2011 DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT TEXT "This publication has been made with the financial support of the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation for Development (AECID) through an FAO trust-fund project, the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (RFLP) for South and Southeast Asia. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the opinion of FAO, AECID, or RFLP.” All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational and other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: Chief Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch Communication Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to: [email protected] © FAO 2011 Bibliographic reference For bibliographic purposes, please -

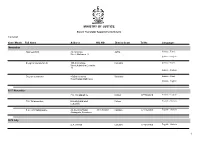

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

02/16/78 No. 77 Maritime Boundaries: India – Sri Lanka

3 MARITIME BOUNDARIES: INDIA-SRI LANKA The Government of the Republic of India and the Republic of Sri Lanka signed an agreement on March 23, 1976, establishing maritime boundaries in the Gulf of Manaar and the Bay of Bengal. Ratifications have been exchanged and the agreement entered into force on May 10, 1976, two years after the two countries negotiated a boundary in the Palk Strait. The full text of the agreement is as follows: AGREEMENT BETWEEN INDIA AND SRI LANKA ON THE MARITIME BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE TWO COUNTRIES IN THE GULF OF MANAAR AND THE BAY OF BENGAL AND RELATED MATTERS The Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the Republic of Sri Lanka, RECALLING that the boundary in the Palk Strait has been settled by the Agreement between the Republic of India and the Republic of Sri Lanka on the Boundary in Historic Waters between the Two Countries and Related Matters, signed on 26/28 June, 1974, AND DESIRING TO extend that boundary by determining the maritime boundary between the two countries in the Gulf of Manaar and the Bay of Bengal, HAVE AGREED as follows: Article I The maritime boundary between India and Sri Lanka in the Gulf of Manaar shall be arcs of Great Circles between the following positions, in the sequence given below, defined by latitude and longitude: Position Latitude Longitude Position 1 m : 09° 06'.0 N., 79° 32'.0 E Position 2 m : 09° 00'.0 N., 79° 31'.3 E Position 3 m : 08° 53'.0 N., 79° 29'.3 E Position 4 m : 08° 40'.0 N., 79° 18'.2 E Position 5 m : 08° 37'.2 N., 79° 13'.0 E Position 6 m : 08° 31'.2 N., 79° 04'.7 E Position 7 m : 08° 22'.2 N., 78° 55'.4 E Position 8 m : 08° 12'.2 N., 78° 53'.7 E Position 9 m : 07° 35'.3 N., 78° 45'.7 E Position 10m : 07° 21'.0 N., 78° 38'.8 E Position 11m : 06° 30'.8 N., 78° 12'.2 E Position 12m : 05° 53'.9 N., 77° 50'.7 E Position 13m : 05° 00'.0 N., 77° 10'.6 E 4 The extension of the boundary beyond Position 13 m will be done subsequently. -

Assessment of Forestry-Related Requirements for Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of Tsunami-Affected Areas of Sri Lanka

ASSESSMENT OF FORESTRY-RELATED REQUIREMENTS FOR REHABILITATION AND RECONSTRUCTION OF TSUNAMI-AFFECTED AREAS OF SRI LANKA MISSION REPORT 10 – 24 MARCH 2005 SIMMATHIRI APPANAH NATIONAL FOREST PROGRAMME ADVISOR (ASIA-PACIFIC) FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................... 1 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 1 2. Background......................................................................................................................... 2 3. Key features of the Mission and approach ...................................................................... 3 4. Impact of the Tsunami....................................................................................................... 4 4.1 General overview ............................................................................................................... 4 4.2 Natural habitats affected by the Tsunami .......................................................................... 5 5. The impact of the Tsunami on natural and manmade ecosystems................................ 7 5.1 Coastlines........................................................................................................................... 7 5.2 Home gardens ...................................................................................................................