Recent Changes in Land-Use in the Pambala–Chilaw Lagoon Complex (Sri Lanka) Investigated Using Remote Sensing and Gis: Conservation of Mangroves Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Evaluation of Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector in Sri Lanka

Evaluation Working Paper Sri Lanka Country Assistance Program Evaluation: Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Assistance Evaluation August 2007 Supplementary Appendix A Operations Evaluation Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 August 2007) Currency Unit — Sri Lanka rupee (SLR) SLR1.00 = $0.0089 $1.00 = SLR111.78 ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank GDP — gross domestic product ha — hectare kg — kilogram TA — technical assistance UNDP — United Nations Development Programme NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Director General Bruce Murray, Operations Evaluation Department (OED) Director R. Keith Leonard, Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Evaluation Team Leader Njoman Bestari, Principal Evaluation Specialist Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Operations Evaluation Department CONTENTS Page Maps ii A. Scope and Purpose 1 B. Sector Context 1 C. The Country Sector Strategy and Program of ADB 11 1. ADB’s Sector Strategies in the Country 11 2. ADB’s Sector Assistance Program 15 D. Assessment of ADB’s Sector Strategy and Assistance Program 19 E. ADB’s Performance in the Sector 27 F. Identified Lessons 28 1. Major Lessons 28 2. Other Lessons 29 G. Future Challenges and Opportunities 30 Appendix Positioning of ADB’s Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Strategies in Sri Lanka 33 Njoman Bestari (team leader, principal evaluation specialist), Alvin C. Morales (evaluation officer), and Brenda Katon (consultant, evaluation research associate) prepared this evaluation working paper. Caren Joy Mongcopa (senior operations evaluation assistant) provided administrative and research assistance to the evaluation team. The guidelines formally adopted by the Operations Evaluation Department (OED) on avoiding conflict of interest in its independent evaluations were observed in the preparation of this report. -

Fisheries and Environmental Profile of Chilaw Estuary

REGIONAL FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA (RFLP) --------------------------------------------------------- Fisheries and environmental profile of Chilaw lagoon: a literature review (Activity 1.3.1 Prepare fisheries and environmental profile of Chilaw lagoon using secondary data and survey reports) For the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia Prepared by Leslie Joseph Co-management consultant June 2011 DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT TEXT "This publication has been made with the financial support of the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation for Development (AECID) through an FAO trust-fund project, the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (RFLP) for South and Southeast Asia. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the opinion of FAO, AECID, or RFLP.” All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational and other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: Chief Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch Communication Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to: [email protected] © FAO 2011 Bibliographic reference For bibliographic purposes, please -

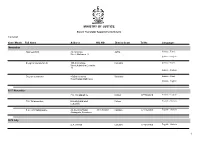

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

02/16/78 No. 77 Maritime Boundaries: India – Sri Lanka

3 MARITIME BOUNDARIES: INDIA-SRI LANKA The Government of the Republic of India and the Republic of Sri Lanka signed an agreement on March 23, 1976, establishing maritime boundaries in the Gulf of Manaar and the Bay of Bengal. Ratifications have been exchanged and the agreement entered into force on May 10, 1976, two years after the two countries negotiated a boundary in the Palk Strait. The full text of the agreement is as follows: AGREEMENT BETWEEN INDIA AND SRI LANKA ON THE MARITIME BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE TWO COUNTRIES IN THE GULF OF MANAAR AND THE BAY OF BENGAL AND RELATED MATTERS The Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the Republic of Sri Lanka, RECALLING that the boundary in the Palk Strait has been settled by the Agreement between the Republic of India and the Republic of Sri Lanka on the Boundary in Historic Waters between the Two Countries and Related Matters, signed on 26/28 June, 1974, AND DESIRING TO extend that boundary by determining the maritime boundary between the two countries in the Gulf of Manaar and the Bay of Bengal, HAVE AGREED as follows: Article I The maritime boundary between India and Sri Lanka in the Gulf of Manaar shall be arcs of Great Circles between the following positions, in the sequence given below, defined by latitude and longitude: Position Latitude Longitude Position 1 m : 09° 06'.0 N., 79° 32'.0 E Position 2 m : 09° 00'.0 N., 79° 31'.3 E Position 3 m : 08° 53'.0 N., 79° 29'.3 E Position 4 m : 08° 40'.0 N., 79° 18'.2 E Position 5 m : 08° 37'.2 N., 79° 13'.0 E Position 6 m : 08° 31'.2 N., 79° 04'.7 E Position 7 m : 08° 22'.2 N., 78° 55'.4 E Position 8 m : 08° 12'.2 N., 78° 53'.7 E Position 9 m : 07° 35'.3 N., 78° 45'.7 E Position 10m : 07° 21'.0 N., 78° 38'.8 E Position 11m : 06° 30'.8 N., 78° 12'.2 E Position 12m : 05° 53'.9 N., 77° 50'.7 E Position 13m : 05° 00'.0 N., 77° 10'.6 E 4 The extension of the boundary beyond Position 13 m will be done subsequently. -

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381)

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Foci and Key Activities 1. In recent years, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Government of Japan have been the major development partners in water supply. Overall, several bilateral development partners are involved in this sector, including (i) Japan (providing support for Kandy, Colombo, towns north of Colombo, and Eastern Province), (ii) Australia (Ampara), (iii) Denmark (Colombo, Kandy, and Nuwaraeliya), (iv) France (Trincomalee), (v) Belgium (Kolonna–Balangoda), (vi) the United States of America (Badulla and Haliela), and (vii) the Republic of Korea (Hambantota). Details of projects assisted by development partners are in the table below. The World Bank completed a major community water supply and sanitation project in 2010. Details of Projects in Sri Lanka Assisted by the Development Partners, 2003 to Present Development Amount Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) Asian Development Jaffna–Killinochchi Water Supply and Sanitation 2011–2016 164 Bank Dry Zone Water Supply and Sanitation 2009–2014 113 Secondary Towns and Rural Community-Based 259 Water Supply and Sanitation 2003–2014 Greater Colombo Wastewater Management Project 2009–2015 100 Danish International Kelani Right Bank Water Treatment Plant 2008–2010 80 Development Agency Nuwaraeliya District Group Water Supply 2006–2010 45 Towns South of Kandy Water Supply 2005–2010 96 Government of Eastern Coastal Towns of Ampara -

Download PDF 638 KB

Working Paper 58 Developing Effective Institutions for Water Resources Management : A Case Study in the Deduru Oya Basin, Sri Lanka P. G. Somaratne K. Jinapala L. R. Perera B. R. Ariyaratne, D. J. Bandaragoda and Ian Makin International Water Management Institute i IWMI receives its principal funding from 58 governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations known as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Support is also given by the Governments of Ghana, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Thailand. The authors: P.G. Somaratne, L. R. Perera, and B. R. Ariyaratne are Senior Research Officers; K. Jinapala is a Research Associate; D. J. Bandaragoda is a Principal Researcher, and Ian Makin is the Regional Director, Southeast Asia, all of the International Water Management Institute. Somaratne, P. G.; Jinapala, K.; Perera, L. R.; Ariyaratne, B. R.; Bandaragaoda, D. J.; Makin, I. 2003. Developing effective institutions for water resources management: A case study in the Deduru Oya Basin, Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute. / river basins / water resource management / irrigation systems / groundwater / water resources development / farming / agricultural development / rivers / fish farming / irrigation programs / poverty / irrigated farming / water shortage / pumps / ecology / reservoirs / water distribution / institutions / environment / natural resources / water supply / drought / land use / water scarcity / cropping systems / agricultural production -

IEE: SRI: Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project: Mannar Water Supply

Initial Environmental Examination Report Project Number: 37381 November 2012 Sri Lanka: DRY ZONE URBAN WATER AND SANITATION PROJECT - for Mannar Water Supply Prepared by Project Management Unit for Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project, Colombo, Sri Lanka. For Water Supply and Drainage Board Ministry of Water Supply and Drainage, Sri Lanka. This report has been submitted to ADB by the Ministry of Water Supply and Drainage and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Project Implementation Agency: National Water Supply & Drainage Board Funding Agency: Asian Development Bank Project Number: 37381-SRI Sri Lanka: Dry Zone Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project (DZUWSSP) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION: MANNAR WATER SUPPLY NOVEMBER 2012 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Purpose of the Report ........................................................................................................................... 1 B. Extent of IEE study ............................................................................................................................... 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ..................................................................................................... 5 A. Type, Category and Need .................................................................................................................... -

Areas Declared Under Urban Development Authority

Point Pedro UC Velvetithurei UC!. !. !. Vadamarachchi PS Valikaman North 8 !. 3 !. 4 B Vadamaradchi South West Kankesanthurai PS Ton daima !. nar d Valla a i Tun o nal ai Roa R d B4 Valikaman West li 17 a !. l d Karainagar PS a a Total Declared Area P o - !. a P R u fn tt i seway a ur a igar Cau J -M h a c Karan e e h Kas sa c ad l o ai Valikaman South West a Roa i K R - d !. o d a m Local Authorities Total LA Declared LA Declared GND's a d a o Valikaman South m R a i !. k a i r d u Jaffna PS Ealuvaitivu o h P t !. K o MC 24 24 712 !. Kayts PS n - in a y t l P V s !. o e e l a Thenmaratchi PS d l u a k ro n n !. P -M a a Analaitivu i u - K r K u UC 41 41 514 !. Jaffna MC th a y B N a y a e av n t !Ha a Chavakachcheri UC k s w ch tku e R e l r s Ro i-K !. n o u a a i R a a d ra o d C iti a i vu d PS 276 203 6837 a -M n a Velanai PS n n a na d y!. P r a a Ro o w a R se d i au d C a ivu y ut la Nainaitivu d a ku T !. -

49 Marine Mollusc Diversity Along the Southwest Coast of Sri Lanka

SHORT COMMUNICATION TAPROBANICA, ISSN 1800–427X. June, 2014. Vol. 06, No. 01: pp. 49–52. © Taprobanica Private Limited, 146, Kendalanda, Homagama, Sri Lanka. http://www.sljol.info/index.php/tapro Marine Mollusc Diversity along the Weiner diversity index. Further analysis was Southwest Coast of Sri Lanka carried out using Cluster and Principle Component Analysis in order to investigate Molluscan species as well as class-level variation in habitat with regard to the diversity is highest in the marine environment distribution and abundance of the species (Russell-Hunter, 1983). The current survey data recorded during the study. reveals that Sri Lanka is inhabited by about 240 species of marine molluscs belonging to four of The results for Shannon-Weiner index revealed the seven classes representing marine molluscs a highest diversity at Tangalle (3.37) and (De Silva, 2006). The study area, along the Negambo (3.36), highest evenness in Negambo southwest coast of Sri Lanka, experiences the (0.051). Panadura showed the lowest diversity southwest monsoon from May to September, (2.68) and the lowest evenness (0.035) (Table which has a significant impact on climate and 1). Some shells were found only at a single site. oceanographic conditions in this region. Several species including Amathina tricarinata, Asaphis deflorata, Cantharus undosus, Sites were selected including those associated Chicoreus brunneus, Conus figulinus, with rocky habitats. Such as, isolated rocks on Dentallium sp., Ficus sp., Globularia fluctuata, sandy beaches or scattered continuous rocks Mesodesma glabratum, Phalium decussatum, along the shoreline. Shells were collected along Pharaonella sp., Terebra sp., Tonna luteostoma a 100m line transect parallel to the shoreline, and Vasticardium assimile were only recorded along the backshore. -

IEE: SRI: Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project

Initial Environmental Examination Report Project Number: 37381-013 November 2012 Sri Lanka: DRY ZONE URBAN WATER AND SANITATION PROJECT – for Chilaw Water System Prepared by Project Management Unit for Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project, Colombo, Sri Lanka. For Water Supply and Drainage Board Ministry of Water Supply and Drainage, Sri Lanka. This report has been submitted to ADB by the Ministry of Water Supply and Drainage and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose of the Report The Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Program (DZUWSP) is intended to facilitate sustainable development in disadvantaged districts in Sri Lanka. This will be achieved by investing in priority water supply and sanitation infrastructure in selected urban areas. Assistance will be targeted in those parts of the Northern and North-Western Provinces with the most acute shortages of drinking water and sanitation. Chosen urban areas are the towns of Mannar, Vavuniya, Puttalam and Chilaw. DZUWSP will be implemented over five years beginning in early 2009, up to 2014 and is supported by ADB through a project loan and grant. The Ministry of Water Supply and Drainage (MWSD) is the Executing Agency (EA) for the program and NWSDB is the Implementing Agency (IA). DZUWSP will improve infrastructure through the development, design and implementation of subprojects in water supply and sanitation in each town. The Project has been classified by ADB as environmental assessment category B, where the component requiring greater attention is the Vavuniya water supply subproject (a 10.5 m high dam and 238.4 ha storage reservoir). -

Ramayana Trail - Highlights

RAMAYANA TRAIL - HIGHLIGHTS 5 NIGHTS | 6 DAYS Day 01 AIRPORT / CHILAW Meet your guide on arrival and transfer to a hotel in Chilaw for overnight stay. Travel to visit Munishwaram Temple & Manavari Temple in Chilaw. Munishwaram Temple. It is believed that Munishwaram predates the Ramayana and a temple dedicated to Lord Shiva was located here. Munishwaram means the first temple for Shiva (Munnu + Easwaran). Manavari Temple Manavari is the first lingam installed and prayed by Rama and till date this lingam is called as Ramalinga Shivan. Rameshwaram is the only other lingam in world named after Lord Rama. Overnight stay at Hotel in Chilaw Day 02 CHILAW / TRINCOMALEE After breakfast, Visit Koneshwaram temple and Shankari Devi temple in Trincomalee. Koneswaram temple Koneswaram temple of Trincomalee (also historically known as the Thirukonamamalai Konesar Kovil, the Temple of the Thousand Pillars and Thiru- Konamamalai Maccakeswaram Kovil) is an Hindu temple in Trincomalee, Eastern Province, Sri Lanka venerated by Saivites throughout the continent. It is built atop Swami Rock, a rocky promontory cape overlooking Trincomalee, a classical period harbour port town. Shankari Devi Temple The famed SHANKARI Temple, in Sri Lanka, is one of the 18 Devi Temples (Ashta Dasha Shakti Peethas). Many have heard the Ashtadasha Shakti Peetha Shloka starting with LANKAAYAAM SHAANKARI DEVI.composed by Sri Adi Shankara which means Shankari in Lanka. This Shloka enumerates the list of places of Devi temples which are considered to be part of the 18 Devi Peethas. Overnight at Hotel in Trincomalee Day 03 TRINCOMALEE / LAKEGALA / DUNUWILA / KANDY After breakfast, En route visit the cartels behind the Dunuvila lake are called Laggala which when translated into English gives us the meaning target rock.