The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce Di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM

State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM Sections Close DONATE NOW ! Arts CommentaCondividi!"#$%& State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? Should museums return art that was originally created for churches to their original locations? Italian Hours by Lucy Gordan https://www.lavocedinewyork.com/en/arts/2020/06/04/state-vs-church-uffizi-director-provokes-controversy-over-who-owns-sacred-art/ Page 1 of 13 State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM Caravaggio's "Four Musicians". Photo: Wikipedia.org Jun 04 2020 “I believe the time has come,” Schmidt said, “for state museums to perform an act of courage and return paintings to the churches for which they were originally created… " . However, this decision is neither popular nor logistically simple for many reasons. For some experts, it's unimaginable. A few days before the official post-Covid-19 reopening of the Uffizi Galleries in Florence on June 2nd, a comment made by its Director, Eike Schmidt, at the ceremony held in the Palazzo Pitti sent shock waves through Italy’s museum community. “I believe the time has come,” he said, “for state museums to perform an act of courage and https://www.lavocedinewyork.com/en/arts/2020/06/04/state-vs-church-uffizi-director-provokes-controversy-over-who-owns-sacred-art/ Page 2 of 13 State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM return paintings to the churches for which they were originally created… Perhaps the most important example is in the Uffizi: the Rucellai Altarpiece by Duccio di Buoninsegna, which in 1948 was removed from the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. -

Our Excursions

Our excursions Tuscany Travel Experiences t.o. FIRENZE Departure/arrival : San Gimignano/ San Gimignano or on request pick up at your accomodation Duration: 6/8 hours Our idea : Discovery the amazing principal monu- ments, but not only .. together discovery the history more ancient and not about one of the most incredible city in the world . Fare clic per aggiungere Highlights: Santa Maria Novella , Duomo, repubblica una foto square, Signoria Square, Palazzo Vecchio, Uffizi ( exte- rior) , Ponte Vecchio, Palazzo Pitti, Santa Croce Operates : Thusday or on request Language: english, italian, french, other languages on request Includes: expert and professional Tour Leader and transportation from San Gimignano (other pick up on request) Price : € 69,00 SIENA Departure/arrival : San Gimignano/ San Gimi- gnano or on request pick up at your accomodation Duration: 6/8 hours Our idea : Lose yourselves in the one of the most beautiful medioeval city, amazing yourselves like Wagner visiting the Dome and learn about “Palio “, “contrade “ and so on … Fare clic per aggiungere Highlights: Piazza del campo, Duomo, battistero, una foto Torre del mangia, S. Domenico. Operates : Wednesday or on request Language: english, italian, french, other languages on request Includes: expert and professional Tour Leader and transportation from San Gimignano (other pick up on request) Price : € 69,00 2 Fare clic per aggiungere una foto VOLTERRA Departure/arrival : San Gimignano/ San Gimignano or on request pick up at your accomodation Duration: 3 hours Our idea : -

Motorway A14, Exit Pesaro-Urbino • Porto Di Ancona: Croatia, Greece, Turkey, Israel, Ciprus • Railway Line: Milan, Bologna, Ancona, Lecce, Rome, Falconara M

CAMPIONATO D’EUROPA FITASC – FINALE COPPA EUROPA EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP San Martino/ Rio Salso di Tavullia – Pesaro/Italia, 17/06/2013 – 24/06/2013 • Motorway A14, exit Pesaro-Urbino • Porto di Ancona: Croatia, Greece, Turkey, Israel, Ciprus • Railway Line: Milan, Bologna, Ancona, Lecce, Rome, Falconara M. • AIRPORT: connection with Milan, Rom, Pescara and the main European capitals: Falconara Ancona “Raffaello Sanzio” 80 KM da Pesaro Forlì L. Ridolfi 80 KM da Pesaro Rimini “Federico Fellini” 30 KM da Pesaro Bologna “Marconi” 156 KM da Pesaro CAMPIONATO D’EUROPA FITASC – FINALE COPPA EUROPA EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP San Martino/ Rio Salso di Tavullia – Pesaro/Italia, 17/06/2013 – 24/06/2013 Rossini tour: Pesaro Pesaro was the birth place of the famous musician called “Il Cigno di Pesaro” A walk through the characteristic streets of the historic centre lead us to Via Rossini where the Rossini House Museum is situated. It is possible to visit his house, the Theatre and the Conservatory that conserve Rossini’s operas and memorabilia. Prices: Half Day tour: € 5.00 per person URBINO URBINO is the Renaissance of the new millennium. Its Ducal Palce built for the grand duke Federico da Montefeltro, with its stately rooms, towers and magnificent courtyard forms a perfect example of the architecture of the time. Today , the building still houses the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche with precious paintings by Piero della Francesca, Tiziano, Paolo Uccello and Raphael, whose house has been transformed into a museum. Not to be missed, are the fifteenth century frescoes of the oratory of San Giovanni and the “Presepio” or Nativity scene of the Oratory of San Giuseppe (entry of Ducal Palace, Oratories) Prices: Half Day tour: € 25.00 per person included: bus - guide – Palazzo Ducale ticket – Raffaello Sanzio’s birthplace ticket CAMPIONATO D’EUROPA FITASC – FINALE COPPA EUROPA EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP San Martino/ Rio Salso di Tavullia – Pesaro/Italia, 17/06/2013 – 24/06/2013 REPUBLIC OF SAN MARINO This is one of the smallest and most interesting Republics in the world. -

Michelangelo's Pieta in Bronze

Michelangelo’s Pieta in Bronze by Michael Riddick Fig. 1: A bronze Pieta pax, attributed here to Jacopo and/or Ludovico del Duca, ca. 1580 (private collection) MICHELANGELO’S PIETA IN BRONZE The small bronze Pieta relief cast integrally with its frame for use as a pax (Fig. 1) follows after a prototype by Michelangelo (1475-1564) made during the early Fig. 2: A sketch (graphite and watercolor) of the Pieta, 1540s. Michelangelo created the Pieta for Vittoria attributed to Marcello Venusti, after Michelangelo Colonna (1492-1547),1 an esteemed noblewoman with (© Teylers Museum; Inv. A90) whom he shared corresponding spiritual beliefs inspired by progressive Christian reformists. Michelangelo’s Pieta relates to Colonna’s Lamentation on the Passion of Pieta was likely inspired by Colonna’s writing, evidenced Christ,2 written in the early 1540s and later published in through the synchronicity of his design in relationship 3 1556. In her Lamentation Colonna vividly adopts the role with Colonna’s prose. of Mary in grieving the death of her son. Michelangelo’s Michelangelo’s Pieta in Bronze 2 Michael Riddick Fig. 3: An incomplete marble relief of the Pieta, after Michelangelo (left; Vatican); a marble relief of the Pieta, after Michelangelo, ca. 1551 (right, Santo Spirito in Sassia) Michelangelo’s original Pieta for Colonna is a debated Agostino Carracci (1557-1602) in 1579.5 By the mid-16th subject. Traditional scholarship suggests a sketch at century Michelangelo’s Pieta for Colonna was widely the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is the original celebrated and diffused through prints as well as painted he made for her while others propose a panel painting and sketched copies. -

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Robert Fredona Working Paper 18-021 Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Harvard Business School Robert Fredona Harvard Business School Working Paper 18-021 Copyright © 2017 by Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona ABSTRACT: N.S.B. Gras, the father of Business History in the United States, argued that the era of mercantile capitalism was defined by the figure of the “sedentary merchant,” who managed his business from home, using correspondence and intermediaries, in contrast to the earlier “traveling merchant,” who accompanied his own goods to trade fairs. Taking this concept as its point of departure, this essay focuses on the predominantly Italian merchants who controlled the long‐distance East‐West trade of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Until the opening of the Atlantic trade, the Mediterranean was Europe’s most important commercial zone and its trade enriched European civilization and its merchants developed the most important premodern mercantile innovations, from maritime insurance contracts and partnership agreements to the bill of exchange and double‐entry bookkeeping. Emerging from literate and numerate cultures, these merchants left behind an abundance of records that allows us to understand how their companies, especially the largest of them, were organized and managed. -

01Ÿ345617859 Ÿ Ÿ 971Ÿ 1Ÿ 897 5

ÿ ÿÿ ÿÿ !"#$ %&'&' ()01 234567ÿ39ÿ@ABAC5D7ÿA4ÿEAFÿAFGÿHAD75CÿIFÿ25CPFIQ3ÿRCASITFU4ÿVWQQACXÿ39ÿD75 Y`S5aa5FSI54ÿ39ÿVDÿ234567ÿbcdefg V367IAÿh3iA pqrrqsÿuvw'ÿxyÿxwuwqyxrÿsq'ÿxuv '&'&xvqyrwy&y&xuv&'&' xuÿqÿuv&u'ÿxyÿxywuw&'ÿqqy' defÿpÿghfiej q kwlvuÿm&lrxuwqy'ÿ0n1n mjo %&ÿxu&wxrÿwyÿuvw'ÿqywxuwqyÿxkÿp&ÿ'pq&uÿuqÿq kwlvuÿy&ÿuv&ÿuÿykÿuv&ÿq kwylÿqÿqywxuwqyÿqÿuvw'ÿxu&wxr pkÿkqÿxkÿp&ÿuv&ÿ'pq&uÿqÿq kwlvuÿ qu&uwqyÿy&ÿuv&ÿu rqÿyquÿ&qs&ÿuvw'ÿyquw& %w'ÿw''&uxuwqyuv&'w'ÿw'ÿpqlvuÿuqÿkqÿpkÿm&'&xvyrwy&trÿjuÿvx' p&&yÿx& u&ÿqÿwyr'wqyÿwyÿ%&'&'ÿpkÿxyÿxuvqwu&ÿxwyw'uxuqÿq m&'&xvyrwy&trÿpqÿq&ÿwyqxuwqyvÿ r&x'&ÿqyuxu &'&xvqyrwy&ty&x CHAPTER ONE: HUSBAND OF THE MOTHER OF GOD Gracián dedicates Book I of his Summary to an exploration of Joseph’s title as “husband of Mary”. Joseph’s role as spouse has been given much attention in biblical commentary, in apocryphal literature, and in the writings of Church Fathers and theologians. The Summary’s emblematic approach to the marriage of Joseph and Mary bears connection with each of these genres as well as with fourteenth and fifteenth-century Italian artistic representations of the scene. Although the Summary’s depiction of the marriage, in particular Blancus’ engraving (Plate 1), conforms to the accounts given in Scriptural and apocryphal narratives, it presents striking divergences when compared to the existing artistic tradition. While artistic depictions of the Marriage of the Virgin traditionally present the event as a publicly celebrated union observed by onlookers, most notably the disappointed unsuccessful suitors competing for Mary’s hand, Blancus “privatises” the union, thus emphasising it and ultimately marriage as a whole as sacred, dignified and divinely ordained. The engraving, along with the accompanying epigram and text de facto, successfully present to the audience a visualisation of the nature of Mary and Joseph’s marriage and of Joseph’s role as spouse. -

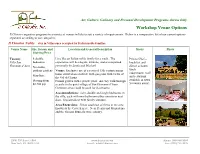

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Local Livings Markedskalender

Specielle sommerbegivenheder og markedskalender i Toscana og Umbrien Side 2 Indholdsfortegnelsen Specielle sommerbegivenheder .. 3 Maj/juni ............................................. 4 Juli ....................................................... 5 Juli/august ............................................. 6 August/september .................................... 7 Markeder ....................................................... 8 Kort over Toscana ............................................9 Lucca ................................................................... 10 Pisa .......................................................................... 11 Firenze ......................................................................... 11 Siena ................................................................................ 12 Arezzo .................................................................................. 13 Kort over Umbrien ................................................................... 14 Perugia .......................................................................................... 15 HUSK! ................................................................................................ 16 Side 3 Specielle sommerbegivenheder Der er mange events i Toscana og Umbrien i løbet af sommermånederne, hvor vejret er varmt og stabilt, og hvor man kan være udenfor næsten hele døgnet. Vi har håndplukket nogle af de begivenheder, som vi synes er interessante for vores Local Living kunder og beskrevet dem herunder. Vores liste er langtfra -

The Pietà in Historical Perspective

The Pietà in historical perspective The Pietà is not a scene that can be found in the Gospels. The Gospels describe Crucifixion (El Greco), Deposition or descent from the Cross (Rubens), Laying on the ground (Epitaphios), Lamentation (Giotto), Entombment (Rogier Van de Weyden) So How did this image emerge? Background one-devotional images • Narrative images from the Gospel, e.g Icon of Mary at foot of cross • Devotional images, where scene is taken out of its historical context to be used for prayer. e.g. Man of Sorrows from Constantinople and print of it by Israhel van Meckenhem. The Pietà is one of a number of devotional images that developed from the 13th century, which went with intense forms of prayer in which the person was asked to imagine themselves before the image speaking with Jesus. It emerged first in the Thuringia area of Germany, where there was a tradition of fine wood carving and which was also open to mysticism. Background two-the position of the Virgin Mary • During the middle ages the position of Mary grew in importance, as reflected in the doctrine of the Assumption (Titian), the image of the coronation of the Virgin (El Greco) • So too did the emphasis on Mary sharing in the suffering of Jesus as in this Mater Dolorosa (Titian) • Further background is provided by the Orthodox image of the threnos which was taken up by Western mystics, and the image of The Virgin of Humility A devotional gap? • So the Pietà, which is not a Gospel scene, started to appear as a natural stage, between the Gospel scenes of the crucifixion smf the deposition or descent from the cross on the one hand, and the stone of annointing, the lamentation, and the burial on the other. -

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Paolo di Giovanni Fei Sienese, c. 1335/1345 - 1411 The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple 1398-1399 tempera on wood transferred to hardboard painted surface: 146.1 × 140.3 cm (57 1/2 × 55 1/4 in.) overall: 147.2 × 140.3 cm (57 15/16 × 55 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.4 ENTRY The legend of the childhood of Mary, mother of Jesus, had been formed at a very early date, as shown by the apocryphal Gospel of James, or Protoevangelium of James (second–third century), which for the first time recounted events in the life of Mary before the Annunciation. The iconography of the presentation of the Virgin that spread in Byzantine art was based on this source. In the West, the episodes of the birth and childhood of the Virgin were known instead through another, later apocryphal source of the eighth–ninth century, attributed to the Evangelist Matthew. [1] According to this account of her childhood, Mary, on reaching the age of three, was taken by her parents, together with offerings, to the Temple of Jerusalem, so that she could be educated there. The child ascended the flight of fifteen steps of the temple to enter the sacred building, where she would continue to live, fed by an angel, until she reached the age of fourteen. [2] The legend linked the child’s ascent to the temple and the flight of fifteen steps in front of it with the number of Gradual Psalms. -

14Th Century Art in Europe (Proto-Renaissance Period)

Chapter 17: 14th Century Art in Europe (Proto-Renaissance Period) • TERMS: loggia, giornata, sinopia, grisaille, gesso, Book of Hours, predella, ogee arch, corbels, tiercerons, bosses, rosettes Timeline of chapter • Culture: Late Medieval • Style: Proto-Renaissance, 1300-1400 Map 17-1 Europe in the Fourteenth Century. 17-2 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Title: Town Hall and Loggia of the Lancers Medium: Stone and brick Date: 1300-1400 Location: Florence, Italy 17-3 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Andrea Pisano Title: Doors showing Life of John The Baptist from Baptistery of San Giovanni Medium: Gilded bronze Date: 1300-1400 Location: Florence, Italy 17-4 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Andrea Pisano Title: Baptism of the Multitude from Doors showing Life of John the Baptist at the Baptistery of San Giovanni Medium: Gilded bronze Date: 1300-1400 Location: Florence, Italy 17-5 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Cimabue Title: Virgin and Child Enthroned Medium: Tempera and gold on wood panel Date: 1300-1400 ”. 17-6 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Giotto di Bondone Title: Virgin and Child Enthroned Medium: Tempera and gold on wood panel Date: 1300-1400 17-7 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Giotto di Bondone Title: Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel Medium: Frescoes Date: 1300-1400 Location: Padua, Italy 17-8 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Giotto di Bondone Title: Marriage at Cana, Raising of Lazarus, Resurrection, and Lamentation/Noli me Tangere from the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel Medium: Frescoes Date: 1300-1400 Location: Padua, Italy . -

Routing Sheet

LC 265 RENAISSANCE ITALY (IT gen ed credit) for May Term 2016: Tentative Itinerary Program Direction and Academic Content to be provided by IWU Professor Scott Sheridan Contact [email protected] with questions! 1 Monday CHICAGO Departure. Meet at Chicago O’Hare International Airport to check-in for May 2 departure flight for Rome. 2 Tuesday ROME Arrival. Arrive (09.50) at Rome Fiumicino Airport and transfer by private motorcoach, May 3 with local assistant, to the hotel for check-in. Afternoon (13.00-16.00) departure for a half- day walking tour (with whisperers) of Classical Rome, including the Colosseum (entrance at 13.40), Arch of Constantine, Roman Forum (entrance), Fori Imperiali, Trajan’s Column, and Pantheon. Gelato! Group dinner (19.30). (D) 3 Wednesday ROME. Morning (10.00) guided tour (with whisperers) of Vatican City including entrances to May 4 the Vatican Rooms and Sistine Chapel. Remainder of afternoon at leisure. Evening (20.30) performance of Accademia d’Opera Italiana at All Saints Church. (B) 4 Thursday ROME. Morning (09.00) departure for a full-day guided walking tour including Piazza del May 5 Campidoglio, Palazzo dei Conservatori, Musei Capitolini (entrance included at 10.00), the Piazza Venezia, Circus Maximus, Bocca della Verità, Piazza Navona, Piazza Campo de’ Fiori, Piazza di Spagna and the Trevi Fountain. (B) 1 5 Friday ROME/RAVENNA. Morning (07.45) departure by private motorcoach to Ravenna with en May 6 route tour of Assisi with local guide, including the Basilica (with whisperers) and the Church of Saint Claire. Check-in at the hotel.