Summary Highlights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speaker Bios

SPEAKERS Randall Luthi, President, National Ocean Industries Association (NOIA) Randall Luthi became President of the National Ocean Industries Association (NOIA) on March 1, 2010. An attorney and rancher from Freedom, Wyoming and a former Speaker of the Wyoming State House of Representatives, Luthi has an impressive background in government service and the private sector. He most recently served as the Director of the Minerals Management Service (MMS) at the Department of the Interior (DOI) from July 2007 through January 2009. Immediately prior to directing MMS, Luthi served as the Deputy Director of the Department’s Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). In 2000, he started the law firm of Luthi & Voyles, LLC, in Thayne, Wyoming, which helped pay for ranching expenses. Luthi’s ranch operation consists of a cow/calf operation and the growing of hay and barley. It is rumored that he actually has more pictures of cows on his phone than people. Ironically, in 1995 Luthi’s career in the Wyoming House of Representatives began with his name being drawn from a cowboy hat by Governor Mike Sullivan to declare him the victor in a tie vote. He served as speaker in 2005 and 2006. As a state legislator, he served on the Judiciary Committee, Management Audit Committee and Management Council. During his legislative career, he also developed an understanding of the importance of royalties paid to the federal government by companies producing energy on our public lands and waters. As Majority Leader and Speaker of the Wyoming House, Luthi was instrumental in formulation of state budgets which relied heavily upon royalties and severance taxes paid by energy companies developing federal leases. -

Compensation & Travel Report

University of Alaska Schedule of Travel for Executive Positions Calendar Year 2010 Name: PAT GAMBLE Position: President Organization: University of Alaska Dates Traveled Conference Transportation Lodging Other Travel Begin End Purpose of Trip Destination Fees Costs M & IE Expenses Expenses Total 5/7/10 Meet with University of Alaska (UA) Executive Vice Fairbanks 430 430 President Wendy Redman and UA Regent Cynthia Henry 6/2/10 6/4/10 Attend UA board of regents (BOR) meeting; attend UA Anchorage 490 362 69 921 Foundation board of trustees meeting 6/16/10 Attend Denali Commission meeting Anchorage 501 501 7/5/10 7/10/10 Participate in round table discussion with Federal Anchorage; Kodiak 279 279 Communications Commissioner Clyburn and Senator Mark Begich; meet with University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) Chancellor Ulmer; meet with family of former ConocoPhillips president Jim Bowles; attend lunch with Ed Rasmuson and Diane Kaplan of the Rasmuson Foundation; attend Alaska Aerospace Corporation board meeting 7/22/10 7/23/10 Attend Task Force on Higher Education and Career Readiness Anchorage 364 203 42 609 meetings 7/27/10 Meet with UAA Alumni Chair Jeff Roe; meet with Dianne Anchorage 484 32 516 Holmes, civic activist with field school programs; meet with Doctor Lex von Hafften of the Alaska Psychiatry residence steering committee, UAA Vice Provost Health Programs Jan Harris and Director of Workforce Development Kathy Craft of the State of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services 8/10/10 8/11/10 Speak at BOR retreat; meet with Al Parrish -

DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* and Other Frequently Asked Questions About Alaska Native Issues and Cultures

DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* And other frequently asked questions about Alaska Native issues and cultures *No, they paid in advance. Read more inside. UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE/ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY Alaska Natives were legally prevented fromestablishingminingclaimsundertheterms legallyprevented oftheminingact. Alaska Nativeswere As thisphotographindicates, otherbarriers therewere ordiscouragingAlaskaNativesfrom preventing participating intheestablishmentofsocialandeconomic structures ofmodern Alaska. Alaska State Library, Winter and Pond Collection, PCA 87-1050 Effects of Colonialism Why do we hear so much about high rates of alcoholism, suicide, and violence in many Alaska Native communities? What is the Indian Child Welfare Act? “The children that were brought to the Eklutna Vocational School were expected to learn the English language. They were not allowed to speak their own language even among themselves.” Alberta Stephan 63 Why do we hear so much about high rates of alcoholism, suicide, and violence in many Alaska Native communities? Like virtually all Northern societies, Alaska suffers from high rates of alcoholism, violence, and suicide in all sectors of its population, regardless of social class or ethnicity. Society as a whole in the United States has long wrestled with problems of alcoholism. As historian Michael Kimmel observes, “…by today's standards, American men of the early national peri- od were hopeless sots…Alcohol was a way of life; even the founding fathers drank heavi- ly…Alcohol was such an accepted part of American life that in 1829 the secretary of war estimated that three quarters of the nation's laborers drank daily at least 4 ounces of distilled spirits.” 1 Many scholars have speculated that economic anxiety and social disconnection fueled this tendency towards alcoholic overuse in non-Native men of the early American nation. -

Summary Report

Offshore Energy Knowledge Exchange Workshop Summary Report Table of Contents 1. List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Workshop Overview.............................................................................................................................. 2 3. Panels and Speakers ............................................................................................................................. 3 4. Keynote Speakers and Overview Panel................................................................................................. 4 Panel 1 Summary: Project Design and Decision-Making .......................................................................... 9 Panel 2 Summary: Construction and Installation ................................................................................... 15 Panel 3 Summary: Safety and Operations .............................................................................................. 21 Panel 4 Summary: Research and Collaboration ...................................................................................... 28 Appendix A. Brief Biographies of Presenters ........................................................................................... A-1 Appendix B. Offshore Energy Workshop Participant List.......................................................................... B-1 Appendix C. Panel Overview and Presentation Links .............................................................................. -

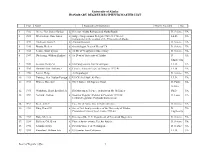

University of Alaska HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS MASTER LIST

University of Alaska HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS MASTER LIST Year Name Biographical Information Degree Awarded Inst. 1. 1932 Steese, Gen. James Gordon d Director, Alaska Railroad and Alaska Roads D. Science UA 2. 1935 Wickersham, Hon. James d Judge; Congressional Delegate 1909-21; 1931-33; LL.D. UA instrumental in the creation of the University of Alaska 3. 1940 Anderson, Jacob P. d Alaskan Botanist D. Science UA 4. 1946 Brandt, Herbert d Ornithologist, Dean of Men at UA D. Science UA 5. 1948 Seaton, Stuart Lyman d 1st Dir of Geophysical Observatory D. Science UA 6. 1949 Duckering, William Elmhirst d 1st Dean of University of Alaska D. UA Engineering 7. 1949 Jackson, Henry M. d US Congressman from Washington LL.D. UA 8. 1950 Dimond, Hon. Anthony J. d Lawyer, Alaska delegate to Congress 1933-45 LL.D. UA 9. 1950 Larsen, Helge Anthropologist D. Science UA 10. 1951 Twining, Gen. Nathan Farragut d US Chief of Staff, Air Force LL.D. UA 11. 1951 Warren, Hon. Earl d Chief Justice, US Supreme Court D. Public UA Service 12. 1951 Washburn, Henry Bradford, Jr. Dir Museum of Science, authority on Mt. McKinley Ph.D. UA 13. 1952 Nerland, Andrew d Board of Regents’ Member & President 1929-56; D. Laws UA territorial legislator; Fairbanks businessman 14. 1952 Reed, John C. Exec Dir of Arctic Inst. of North America D. Science UA 15. 1953 Patty, Ernest N. d One of first faculty members of the University of Alaska; D. UA President of University of Alaska 1953-60 Engineering 16. 1953 Tuve, Merle A. -

The Republican Party of Alaska." Iinity of Promise

Date Printed: 06/16/2009 JTS Box Number: IFES 75 Tab Number: 1 Document Title: State of Alaska Official Election Pamphlet -- Region I Document Date: Nov-96 Document Country: United States -- Alaska Document Language: English IFES ID: CE02029 III A B -~III~II 4 E AI~ B 111~n~ 6 3 A o NOVEMBER 5, 1996 Table of Contents Letter of Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Absentee Voting and Other Special Services ....................................................................................................... 4 The Alaska Permanent Fund Information ........................................................................................................... II Political Parties Statements .................................................................................................................................. 16 Ballot Measures ................................................................................................................................................ 22 Sample Ballot ....................................................................................................................................... 23 Ballot Measure I .................................................................................................. :............................... 24 Ballot Measure 2 ................................................................................................................................ -

THE HISTORY of the COMMUNITY and FAMILES of FREEDOM WYOMING & IDAHO

THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNITY And FAMILES of FREEDOM WYOMING & IDAHO CONTAINING FAMILY HISTORIES STORIES AND OTHER HISTORICAL AND TRIVIAL INFORMATION 1ST EDITION Compiled in 1994-2008 Copyright ©1994-2008 Update date: 5/1/2008 PREFACE This book could not have been published without the perseverance, patience, time, and love provided by Lorna Haderlie. Assistants that contributed time to help type, compile and proof read, were: Judy Clinger, Melvin Clinger, Carole Hokanson, Elaine Jenkins, Annette Luthi, Bonnie Pantuso, Corey Pantuso, Julie Pantuso, Marie Pantuso, Stefanie Pantuso and those that submitted the information contained here within. The Freedom History was assembled from family History's and records submitted by the families, friends, and individuals contained, and not contained in this book. Any misrepresentations by editing were not intentional. The enormous job of compiling this amount of material from so many sources is bound to have created some errors. The many hundreds of donated hours were hard to coordinate. Any omission of material is probably because it was not submitted or missed but not intentional. Any conflicts that may exist between the histories contained in this book may be because they are personal memories and perspectives of each individual submitter. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS History Of Freedom Wyoming 07/21/95 E71 10 Freedom Amusement Hall 09/01/96 E110 21 Freedom Cemetery 10/03/94 E44 22 Freedom Cemetery’s 6/14/00 23 Ruth Haderlie’s Dance 04/25/94 E26 26 Ode To The "Valley" 10/03/94 E46 27 A Story About Polygamists -

12.1025 Ocean Leadership Board Meeting Agenda Book

Members Meeting and Board of Trustees Meeting October 25-26, 2012 Washington, DC October 15, 2012 Dear Member Colleagues, Enclosed please find the Agenda Book for the Members and Board of Trustees meetings scheduled for October 25th and 26th in the conference facilities of the Ocean Leadership offices at 1201 New York Avenue, N.W. in Washington, DC. The Members Meeting is scheduled to begin at 8:30 a.m. on Thursday, October 25th and will conclude by 5:30 p.m. The meeting will be followed by a reception at Old Ebbitt Grill, located at 675 15th Street, N.W. I am very pleased that we have been able to confirm representative speakers from across the federal sector to discuss programs, priorities and federal funding issues of importance to our Members and to the broader ocean sciences community. Please take special note that the ad hoc Bylaws Committee will make a number of recommendations to the Voting Members regarding revisions to the Ocean Leadership Bylaws. Among other items, the proposed revisions include changes to the qualifications for Associate Member status and to the way in which Trustees are elected to the Board of Trustees. A redline document highlighting all the proposed revisions is included in this Agenda Book (see Agenda Item #14 of the Members Meeting). Please take some time to review this document carefully, as some of the recommended revisions represent substantial changes in the way Ocean Leadership’s membership and governance structure operates. On Friday, October 26th please note that the Board will meet in Executive Session at 8:00 a.m. -

The University of Wyoming College of Law at 100: a Brief History

Wyoming Law Review Volume 21 Number 2 Article 1 2021 The University of Wyoming College of Law at 100: A Brief History Klint W. Alexander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alexander, Klint W. (2021) "The University of Wyoming College of Law at 100: A Brief History," Wyoming Law Review: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlr/vol21/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wyoming Law Review by an authorized editor of Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. Alexander: The University of Wyoming College of Law at 100 WYOMING LAW REVIEW VOLUME 21 2021 NUMBER 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING COLLEGE OF LAW AT 100: A BRIEF HISTORY* Klint W. Alexander** I. Introduction .....................................................................................211 II. Justice and Legal Training on the Wyoming Frontier: The Early Years ..................................................................................212 III. The Founding of a Law School in Wyoming ..................................214 IV. The College of Law Takes Off .........................................................217 V. The Next Fifty Years: Beyond a Small, Rural Wyoming Law School .........................................................................................226 VI. Closing Out the Century ................................................................242 -

Sixty-Sixth Legislature

2021-2022 DIRECTORY SIXTY-SIXTH LEGISLATURE The Wyoming Trucking Association and the Associated General Contractors of Wyoming are providing this Legislative Directory as an aid to legislators, government officials, lobbyists, the news media and Wyoming citizens whose duties during the legislative session require fast, dependable communications. We trust this directory will be a useful guide in providing necessary information and will enable you to get in touch more quickly and easily with those whom you have occasion to contact. A digital version of this directory is available at www.wytruck.org and www.agcwyo.org. Wyoming Trucking Association, Inc. Sheila D. Foertsch Managing Director P.O. Box 1175 Casper, WY 82602 (307)234-1579 E-mail: [email protected] Associated General Contractors of Wyoming Katie Legerski Executive Director P.O. Box 965 Cheyenne, WY 82003-0965 (307) 632-0573 (307) 631-9602 cell E-mail: [email protected] We would like to thank the following Wyoming Trucking Association members for their financial contribution toward the publication and distribution of this Legislative Directory. SPONSORS: Admiral Transport Corp. Black Hills Trucking, Inc. John Bunning Transfer Co. Diamond L Trucking Dixon Bros., Inc. Eitel Trucking Co. Mike Hutton MLT Trucking Mountain Cement Co. Ryan Bros. Trucking Sinclair Trucking Co. Wert's Welding & Tank Service CONTENTS Legislative Contact and Bill Status Information ............................................. ii Addresses of Wyoming Officials ................... 1 Wyoming Congressional Delegation -

2010 Annual Report University of Alaska Foundation Over 5,300 Alumni, Staff, Faculty, Parents and Friends Supported the University of Alaska This Year

Seeds of Promise 2010 Annual Report University of Alaska Foundation Over 5,300 alumni, staff, faculty, parents and friends supported the University of Alaska this year. The University of Alaska Foundation seeks, secures and stewards philanthropic support to build excellence at the University of Alaska. 2 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FOUNDATION FY10 ANNUAL REPORT University of Alaska Foundation FY10 Annual Report Table of Contents Foundation Leaders 4-5 2010 Bullock Prize for Excellence 6-7 Lifetime Giving Recognition 8-9 Legacy Society 10-11 Endowment Administration 12-13 Celebrating Support 14-22 Many Ways to Give 23-24 Tax Credit Changes 25 Scholarships 26-41 Honor Roll of Donors 42-67 Financial Statements 68-88 Donor Bill of Rights 89 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FOUNDATION FY10 ANNUAL REPORT 3 FY10 Foundation Leaders Board of Trustees Executive Committee Finance and Audit Committee Sharon Gagnon, Chair (6/09 –11/09) Sharon Gagnon, Chair Ann Parrish, Chair Mike Felix, Vice Chair (6/09 –11/09) Mike Felix, Chair Cheryl Frasca, Vice Chair Mike Felix, Chair (11/09–6/10) Jo Michalski Will Anderson Jo Michalski, Vice Chair (11/09–6/10) Carla Beam Laraine Derr Carla Beam, Secretary Mark Hamilton Darren Franz Susan Anderson Ann Parrish Garry Hutchison Will Anderson Mary Rutherford, Ex-officio Wendy King Alison Browne Bob Mitchell Leo Bustad Committee on Trusteeship Melody Schneider Angela Cox Alison Browne, Chair Sharon Gagnon, Ex-officio Ted Fathauer Mary K. Hughes Mike Felix, Ex-officio Patrick Gamble Ann Parrish Mary Rutherford, Ex-officio Greg Gursey Arliss Sturgulewski Mark Hamilton Carolyne Wallace Investment Committee Mary K. -

Randall Luthi Director of Minerals Management Service

Office of the Secretary For Immediate Release: Contact: Shane Wolfe (DOI) July 23, 2007 202-208-6416 Drew Malcomb (MMS) 202-208-3985 Secretary Kempthorne Names Randall Luthi Director of Minerals Management Service WASHINGTON - Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne today announced the appointment of Randall Luthi as director of the Minerals Management Service (MMS). Kempthorne made the appointment based on a recommendation by Assistant Secretary for Land and Minerals Management C. Stephen Allred. Luthi, currently deputy director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is a former speaker and majority leader of the Wyoming House of Representatives. He previously served in the Department of the Interior and at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). He is a rancher who has also worked as an attorney in private practice. "Randall Luthi’s past experience, including as a leader in the Wyoming legislature, counselor at NOAA and attorney at Interior, make him well suited to head the MMS," Kempthorne said. “This experience, combined with his leadership skills, will enable the MMS to continue to substantially contribute to our goal of reducing America’s dependence on foreign sources of energy through safe and environmentally responsible offshore production while also ensuring that the American public receives a fair share of the value of resources extracted from our public lands and waters.” Prior to being named deputy director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in February 2007, Luthi was a partner in the Luthi and Voyles law firm in Thayne, Wyoming. He was first elected to the Wyoming House of Representatives in 1995, and served as speaker in 2005 and 2006.