The Science of Ocean, Coastal and Great Lakes Restoration Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compensation & Travel Report

University of Alaska Schedule of Travel for Executive Positions Calendar Year 2010 Name: PAT GAMBLE Position: President Organization: University of Alaska Dates Traveled Conference Transportation Lodging Other Travel Begin End Purpose of Trip Destination Fees Costs M & IE Expenses Expenses Total 5/7/10 Meet with University of Alaska (UA) Executive Vice Fairbanks 430 430 President Wendy Redman and UA Regent Cynthia Henry 6/2/10 6/4/10 Attend UA board of regents (BOR) meeting; attend UA Anchorage 490 362 69 921 Foundation board of trustees meeting 6/16/10 Attend Denali Commission meeting Anchorage 501 501 7/5/10 7/10/10 Participate in round table discussion with Federal Anchorage; Kodiak 279 279 Communications Commissioner Clyburn and Senator Mark Begich; meet with University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) Chancellor Ulmer; meet with family of former ConocoPhillips president Jim Bowles; attend lunch with Ed Rasmuson and Diane Kaplan of the Rasmuson Foundation; attend Alaska Aerospace Corporation board meeting 7/22/10 7/23/10 Attend Task Force on Higher Education and Career Readiness Anchorage 364 203 42 609 meetings 7/27/10 Meet with UAA Alumni Chair Jeff Roe; meet with Dianne Anchorage 484 32 516 Holmes, civic activist with field school programs; meet with Doctor Lex von Hafften of the Alaska Psychiatry residence steering committee, UAA Vice Provost Health Programs Jan Harris and Director of Workforce Development Kathy Craft of the State of Alaska Department of Health and Social Services 8/10/10 8/11/10 Speak at BOR retreat; meet with Al Parrish -

DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* and Other Frequently Asked Questions About Alaska Native Issues and Cultures

DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* And other frequently asked questions about Alaska Native issues and cultures *No, they paid in advance. Read more inside. UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE/ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY Alaska Natives were legally prevented fromestablishingminingclaimsundertheterms legallyprevented oftheminingact. Alaska Nativeswere As thisphotographindicates, otherbarriers therewere ordiscouragingAlaskaNativesfrom preventing participating intheestablishmentofsocialandeconomic structures ofmodern Alaska. Alaska State Library, Winter and Pond Collection, PCA 87-1050 Effects of Colonialism Why do we hear so much about high rates of alcoholism, suicide, and violence in many Alaska Native communities? What is the Indian Child Welfare Act? “The children that were brought to the Eklutna Vocational School were expected to learn the English language. They were not allowed to speak their own language even among themselves.” Alberta Stephan 63 Why do we hear so much about high rates of alcoholism, suicide, and violence in many Alaska Native communities? Like virtually all Northern societies, Alaska suffers from high rates of alcoholism, violence, and suicide in all sectors of its population, regardless of social class or ethnicity. Society as a whole in the United States has long wrestled with problems of alcoholism. As historian Michael Kimmel observes, “…by today's standards, American men of the early national peri- od were hopeless sots…Alcohol was a way of life; even the founding fathers drank heavi- ly…Alcohol was such an accepted part of American life that in 1829 the secretary of war estimated that three quarters of the nation's laborers drank daily at least 4 ounces of distilled spirits.” 1 Many scholars have speculated that economic anxiety and social disconnection fueled this tendency towards alcoholic overuse in non-Native men of the early American nation. -

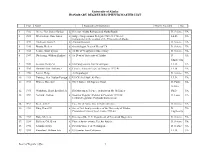

University of Alaska HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS MASTER LIST

University of Alaska HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS MASTER LIST Year Name Biographical Information Degree Awarded Inst. 1. 1932 Steese, Gen. James Gordon d Director, Alaska Railroad and Alaska Roads D. Science UA 2. 1935 Wickersham, Hon. James d Judge; Congressional Delegate 1909-21; 1931-33; LL.D. UA instrumental in the creation of the University of Alaska 3. 1940 Anderson, Jacob P. d Alaskan Botanist D. Science UA 4. 1946 Brandt, Herbert d Ornithologist, Dean of Men at UA D. Science UA 5. 1948 Seaton, Stuart Lyman d 1st Dir of Geophysical Observatory D. Science UA 6. 1949 Duckering, William Elmhirst d 1st Dean of University of Alaska D. UA Engineering 7. 1949 Jackson, Henry M. d US Congressman from Washington LL.D. UA 8. 1950 Dimond, Hon. Anthony J. d Lawyer, Alaska delegate to Congress 1933-45 LL.D. UA 9. 1950 Larsen, Helge Anthropologist D. Science UA 10. 1951 Twining, Gen. Nathan Farragut d US Chief of Staff, Air Force LL.D. UA 11. 1951 Warren, Hon. Earl d Chief Justice, US Supreme Court D. Public UA Service 12. 1951 Washburn, Henry Bradford, Jr. Dir Museum of Science, authority on Mt. McKinley Ph.D. UA 13. 1952 Nerland, Andrew d Board of Regents’ Member & President 1929-56; D. Laws UA territorial legislator; Fairbanks businessman 14. 1952 Reed, John C. Exec Dir of Arctic Inst. of North America D. Science UA 15. 1953 Patty, Ernest N. d One of first faculty members of the University of Alaska; D. UA President of University of Alaska 1953-60 Engineering 16. 1953 Tuve, Merle A. -

The Republican Party of Alaska." Iinity of Promise

Date Printed: 06/16/2009 JTS Box Number: IFES 75 Tab Number: 1 Document Title: State of Alaska Official Election Pamphlet -- Region I Document Date: Nov-96 Document Country: United States -- Alaska Document Language: English IFES ID: CE02029 III A B -~III~II 4 E AI~ B 111~n~ 6 3 A o NOVEMBER 5, 1996 Table of Contents Letter of Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Absentee Voting and Other Special Services ....................................................................................................... 4 The Alaska Permanent Fund Information ........................................................................................................... II Political Parties Statements .................................................................................................................................. 16 Ballot Measures ................................................................................................................................................ 22 Sample Ballot ....................................................................................................................................... 23 Ballot Measure I .................................................................................................. :............................... 24 Ballot Measure 2 ................................................................................................................................ -

12.1025 Ocean Leadership Board Meeting Agenda Book

Members Meeting and Board of Trustees Meeting October 25-26, 2012 Washington, DC October 15, 2012 Dear Member Colleagues, Enclosed please find the Agenda Book for the Members and Board of Trustees meetings scheduled for October 25th and 26th in the conference facilities of the Ocean Leadership offices at 1201 New York Avenue, N.W. in Washington, DC. The Members Meeting is scheduled to begin at 8:30 a.m. on Thursday, October 25th and will conclude by 5:30 p.m. The meeting will be followed by a reception at Old Ebbitt Grill, located at 675 15th Street, N.W. I am very pleased that we have been able to confirm representative speakers from across the federal sector to discuss programs, priorities and federal funding issues of importance to our Members and to the broader ocean sciences community. Please take special note that the ad hoc Bylaws Committee will make a number of recommendations to the Voting Members regarding revisions to the Ocean Leadership Bylaws. Among other items, the proposed revisions include changes to the qualifications for Associate Member status and to the way in which Trustees are elected to the Board of Trustees. A redline document highlighting all the proposed revisions is included in this Agenda Book (see Agenda Item #14 of the Members Meeting). Please take some time to review this document carefully, as some of the recommended revisions represent substantial changes in the way Ocean Leadership’s membership and governance structure operates. On Friday, October 26th please note that the Board will meet in Executive Session at 8:00 a.m. -

2010 Annual Report University of Alaska Foundation Over 5,300 Alumni, Staff, Faculty, Parents and Friends Supported the University of Alaska This Year

Seeds of Promise 2010 Annual Report University of Alaska Foundation Over 5,300 alumni, staff, faculty, parents and friends supported the University of Alaska this year. The University of Alaska Foundation seeks, secures and stewards philanthropic support to build excellence at the University of Alaska. 2 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FOUNDATION FY10 ANNUAL REPORT University of Alaska Foundation FY10 Annual Report Table of Contents Foundation Leaders 4-5 2010 Bullock Prize for Excellence 6-7 Lifetime Giving Recognition 8-9 Legacy Society 10-11 Endowment Administration 12-13 Celebrating Support 14-22 Many Ways to Give 23-24 Tax Credit Changes 25 Scholarships 26-41 Honor Roll of Donors 42-67 Financial Statements 68-88 Donor Bill of Rights 89 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FOUNDATION FY10 ANNUAL REPORT 3 FY10 Foundation Leaders Board of Trustees Executive Committee Finance and Audit Committee Sharon Gagnon, Chair (6/09 –11/09) Sharon Gagnon, Chair Ann Parrish, Chair Mike Felix, Vice Chair (6/09 –11/09) Mike Felix, Chair Cheryl Frasca, Vice Chair Mike Felix, Chair (11/09–6/10) Jo Michalski Will Anderson Jo Michalski, Vice Chair (11/09–6/10) Carla Beam Laraine Derr Carla Beam, Secretary Mark Hamilton Darren Franz Susan Anderson Ann Parrish Garry Hutchison Will Anderson Mary Rutherford, Ex-officio Wendy King Alison Browne Bob Mitchell Leo Bustad Committee on Trusteeship Melody Schneider Angela Cox Alison Browne, Chair Sharon Gagnon, Ex-officio Ted Fathauer Mary K. Hughes Mike Felix, Ex-officio Patrick Gamble Ann Parrish Mary Rutherford, Ex-officio Greg Gursey Arliss Sturgulewski Mark Hamilton Carolyne Wallace Investment Committee Mary K. -

State of State of Alaska Official Election Pamphlet

STATE OF STATEALASKA OF OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET November 5, 2002 NovemberNovember 5 5,, 2002 2002 REGION lV: NORTHERN ALASKA, WESTERN COASTAL ALASKA, ALEUTIANS This publication was produced by the Division of Elections at a cost of $0.50 per copy. Its purpose is to inform Alaskan voters about candidates and issues appearing on the 2002 General Election Ballot. It was printed in Salem, Oregon. This publication is required by Alaska Statute 15.58.010. The 2002 Official Election Pamphlet was compiled and designed by Division of Elections staff: Henry Webb, coordinator; Mike Matthews, map production. STATE OF STATE OF ALASKA OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET STATE OF OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET Table of Contents Election Day is Tuesday, November 5, 2002 Special Voting Needs and Assistance----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 Voter Eligibility and Polling Places--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 Absentee Voting Information----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 Redistricting Information----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------9 Candidates for Elected Office--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13 List of Candidates for Elected Office-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------14 -

Centennial Edition 1913 - 2013

Key to Political Party Affiliation Designations (AIP) Alaskan Independence (L) Libertarian (D) Democrat (NP) No Party (HR) Home Rule (P) Progressive (I) Independent (PD) Progressive Democrat (ID) Independent Democrat (PHR) Progressive Home Rule (IR) Independent Republican (R) Republican Published by: The Legislative Affairs Agency State Capitol, Room 3 Juneau, AK 99801 (907) 465-3800 This publication is also available online at: http://w3.legis.state.ak.us/pubs/pubs.php ALASKA LEGISLATURE ROSTER OF MEMBERS CENTENNIAL EDITION 1913 - 2013 Also includes Delegates to and Officers of the Alaska Constitutional Convention (1955-56), Governors, and Alaska Congressional Representatives since 1913 2013 In 2012, the Alaska Legislative Celebration Commission was created when the Legislature passed Senate Concurrent Resolution 24. Seven Alaskans were named to the Commission which organized events to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the First Territorial Legislature: two senators, two representatives and three members of the public. In addition, the Commission includes two alternate members, one from the Senate and another from the House of Representatives. The Alaska Legislative Centennial Commission consists of the following members: Senator Gary Stevens, Chair Senator Lyman Hoffman Representative Mike Chenault Representative Bill Stoltze Member Member Member Terrence Cole Rick Halford Clem V. Tillion Public Member Public Member Public Member Senator Anna Fairclough Representative Cathy Muñoz Alternate Member Alternate Member FORWARD Many staff and Legislators have been involved in creating this Centennial Edition of our annual Roster of Members. I want to thank all of them for their hard work and willingness to go beyond expectations. We have had nearly 800 individual Legislators in the past 100 years. -

Directory Of

State of Alaska Division of Elections Media Packet General Election November 6, 2018 Table of Contents Section 1 Letter of Introduction…………………………………………………...Page 4 Teleconference Dates………………………………………………….Page 5 Election Contact Information…………………………………………..Page 6 Important Dates ………………………………………………………...Page 7 Voting Information………………………………………………………Page 8 Voter Eligibility (Frequently Asked Questions)………………………Page 9 Polling Places…………………………………………………………...Page 10 Section 2 What’s on the 2016 General Election Ballot…………………………Page 12 Ballot Measures…………………………………………………………Page 12 House and Senate District Designations……………………………..Page 13 Judicial Districts…………………………………………………………Page 14 Election Results…………………………………………………………Page 15 Sample Election Results……………………………………………….Page 16 House District 99 Explanation…………………………………………Page 19 Early, Absentee and Questioned Ballot Information………………..Page 19 Section 3 Alaska’s Ballot Counting System……………………………………..Page 24 Optical Scan and Hand Count Precincts…………………………….Page 25 Election Security ……………………………………………………….Page 35 General Election Voter Turnout……………………………………….Page 37 State Review Board…………………………………………………….Page 38 Recounting the Ballots…………………………………………………Page 38 Election Recounts (statutes and statistics)…………………………..Page 39 2 Section 1 Letter of Introduction Teleconference Dates Election Contact Information Important Dates Voting Information Voter Eligibility (Frequently Asked Questions) Polling Places Don’t forget to check the Division of Elections’ website for information. www.elections.alaska.gov 3 Director’s Office Elections Offices 240 Main Street Suite 400 Absentee-Petition 907-270-2700 P.O. Box 110017 Anchorage 907-522-8683 Juneau, Alaska 99811-0017 Fairbanks 907-451-2835 907-465-4611 907-465-3203 Juneau 907-465-3021 [email protected] Nome 907-443-5285 Mat-Su 907-373-8952 STATE OF ALASKA Division of Elections Office of the Lieutenant Governor October 23, 2018 Dear Statewide Press, We look forward to working with you as we conduct the November 6, 2018 General Election. -

Aedcconnections

WELCOME! TO OUR new INVestoRS: AEDC STAFF 4th Quarter, 2007 Bob Poe The Arts are Big Business Bill Popp Princess Tours in Anchorage President & CEO Scott Balice Strategies, LLC connections Arts & Economic Prosperity III, a national survey from promoters of the arts, Erin Ealum RenewinG INVestoRS: AEDC shows that nonprofit arts and culture are a thriving industry in Anchorage – one Business & Economic The Newsletter of AK Supply, Inc. that generates $45.16 million in annual economic activity. Development Director Anchorage Economic Alaska Interstate Construction Development Alaska InvestNet According to the survey, this spending–$27.91 million by nonprofit arts and Heather Gould Corporation culture organizations and an additional $17.25 million in event-related spending Communications Alaska National Insurance Co. Director by their audiences—supports 1,168 full-time equivalent jobs, generates $24.24 Alaska Railroad Corporation million in household income to local residents, and delivers $3.84 million in local Alaska Rubber and Supply, Inc. and state government revenue. Not included in the study was spending by individ- Hallie Bissett WHAT’S INSIDE Alaska Telecom, Inc. ual artists and the for-profit arts and culture sector – such as for-profit arts groups, Logistics & International Trade Alaska Considers Increased Oil Taxes Anchorage Council of Bldg artists, photographers, painters, sculptors or the multi-million dollar expansion of Director & Construction Trades Unions the Anchorage Museum of History and Art at the Rasmuson Center. page 1 New rate will be the highest in North America Carr-Gottstein Properties Kari Mahar Chugach Electric Association, Inc. Alaska Considers Platinum Investor Spotlight While the study focused solely on the economic impact of the nonprofit arts, the Investor Relations & Incrreased Oil Taxes Events Coordinator City Electric, Inc. -

State of State of Alaska Official Election Pamphlet

STATE OF STATEALASKA OF OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET November 5, 2002 NovemberNovember 5 5,, 2002 2002 REGION ll: MUNICIPALITY OF ANCHORAGE, MATANUSKA-SUSITNA BOROUGH, WHITTIER, HOPE This publication was produced by the Division of Elections at a cost of $0.50 per copy. Its purpose is to inform Alaskan voters about candidates and issues appearing on the 2002 General Election Ballot. It was printed in Salem, Oregon. This publication is required by Alaska Statute 15.58.010. The 2002 Official Election Pamphlet was compiled and designed by Division of Elections staff: Henry Webb, coordinator; Mike Matthews, map production. STATE OF STATE OF ALASKA OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET STATE OF OFFICIAL ELECTION PAMPHLET Table of Contents Election Day is Tuesday, November 5, 2002 Special Voting Needs and Assistance-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 Voter Eligibility and Polling Places---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 Absentee Voting Information-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------4 Redistricting Information----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------9 Candidates for Elected Office--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13 List of Candidates for Elected Office----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------14 -

North to the Future: Opportunities and Change in Alaska’S Emerging Frontiers

North to the Future: Opportunities and Change in Alaska’s Emerging Frontiers Thursday, October 16, 2014 8:30 - 4:00 p.m. UAA/APU Consortium Library, LIB 307 Sponsored by UAA Justice Center Alaska Law Review Arctic Law Section, Alaska Bar Association Approved for 4.5 general CLE credits by the Alaska Bar Association Justice Center University of Alaska Anchorage Anchorage, Alaska 99508 Copyright © 2014 Alaska Law Review, Duke University School of Law Printed in the United States of America UAA is an EEO/AA employer and educational institution. 1 Agenda 8:30am–9:00am: Arrivals & CLE Registration (Light Breakfast) 9:00am–9:15am: Welcome and Introductory Comments -- Prof. Tom Metzloff, Alaska Law Review Advisor and Dr. André Rosay, UAA Justice Center 9:15am–10:00am: Keynote Speaker - Fran Ulmer, Arctic Research Commission 10:00am-10:15am: Break 10:15am–11:30am: Panel I — “Alaska Native Participation in the Territorial Governance of the North” Moderator: Prof. Ryan Fortson, UAA Justice Center Presenters: Mara Kimmel, Barrett Ristroph Commentators: Joe Evans, City Attorney of Kotzebue; Dan Cheyette Attorney at the Bristol Bay Native Corporation 11:30am-11:45am Alaska Bar Arctic Law Section, Section Meeting 11:45am–1:00pm: Lunch with Keynote Speaker - Willie Hensley, UAA Visiting Distinguished Professor 1:00pm–2:15pm: Panel II— “Alaska’s Role in Managing the Development of the Arctic North” Moderator: Prof. Thomas Metzloff, Duke University School of Law Presenters: Betsy Baker, Barry Zellen Commentators: Bruce Anders, Attorney at CIRI – Cook Inlet Region, Inc. 2:15pm-2:30pm Break 2:30pm–3:45pm: Panel III— “Regulatory Oversight of Alaska’s Arctic Shores” Moderator: Prof.