RICE UNIVERSITY the Aesthetic of Difficulty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Editions of Three Works for Winds by Gyorgy Druschetzky

PERFORMANCE EDITIONS OF THREE WORKS FOR WINDS BY GYORGY DRUSCHETZKY Brandon K. McDannald, B.M.E., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: William Scharnberg, Major Professor Peter Mondelli, Committee Member Kathleen Reynolds, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School McDannald, Brandon K. Performance Editions of Three Works for Winds by Gyorgy Druschetzky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 266 pp., 3 appendices, references, 23 titles. Gyorgy Druschetzky was a noted Czech composer of Harmoniemusik, who wrote more than 150 partitas and serenades, along with at least thirty-two other selections for larger wind groups. This is in addition to twenty-seven symphonies, eleven concertos (most for wind instruments), two fantasias, forty-seven string quartets, two operas, a ballet that is lost, and other miscellaneous chamber music for various combinations of wind/string instruments. Three of his works for winds have existed only in manuscript form since their composition: Concerto in E-flat pour 2 clarinett en B, 2 cors en E-flat, 2 fagott; Overture to Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte; and Partitta a la camera a corno di bassetto primo, secondo, terzo, due corno di caccia, due fagotti. These works remain remarkably interesting to modern ears and deserve to be heard in the twenty-first century. Along with a brief examination of Druschetzky’s life and how it figures into the history of Harmoniemusik, this work presents each piece edited into a modern performance edition. -

Departamento De Filosofía

DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOSOFÍA APROXIMACIÓN AL LENGUAJE DE OLIVIER MESSIAEN: ANÁLISIS DE LA OBRA PARA PIANO VINGT REGARS SUR L’ENFANT - JESÚS FRANCISCO JAVIER COSTA CISCAR UNIVERSITAT DE VALENCIA Servei de Publicacions 2004 Aquesta Tesi Doctoral va ser presentada a Valencia el día 12 de Febrer de 2004 davant un tribunal format per: - D. Francisco José León Tello - D. Salvador Seguí Pérez - D. Antonio Notario Ruiz - D. Francisco Carlos Bueno Camejo - Dª. Carmen Alfaro Gómez Va ser dirigida per: D. Román De La Calle D. Luis Blanes ©Copyright: Servei de Publicacions Francisco Javier Costa Ciscar Depòsit legal: I.S.B.N.:84-370-5899-6 Edita: Universitat de València Servei de Publicacions C/ Artes Gráficas, 13 bajo 46010 València Spain Telèfon: 963864115 UNIVERSIDAD DE VALENCIA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACION AREA DE ESTETICA Y TEORIA DEL ARTE APROXIMACION AL LENGUAJE DE OLIVIER MESSIAEN: ANALISIS DE LA OBRA PARA PIANO VINGT REGARDS SUR L´ ENFANT - JESUS TESIS DOCTORAL REALIZADA POR: FRANCISCO JAVIER COSTA CISCAR DIRIGIDA POR LOS DOCTORES: DR. D. LUIS BLANES ARQUES DR. D. ROMAN DE LA CALLE VALENCIA 2003 I N D I C E 1.- Introducción ........................................................................ 5 2.- Antecedentes e influencias estilísticas en el lenguaje de Olivier Messiaen ........................................... 10 3.- Elementos musicales del lenguaje de Messiaen y su aplicación en la obra para piano Vingt Regards sur l ´ Enfant - Jésus ........................................................ 15 4.- Vingt Regards sur l ´ Enfant - Jésus : Datos Generales. Características de su escritura pianística .................. 42 5.- Temática, simbología e iconografía en Vingt Regards sur l ´ Enfant - Jésus ........................................................ 45 6.- Análisis Formal de la obra .......................................... 67 7.- Evolución de los Temas de la obra: Estudio comparativo de su desarrollo y presentación ........ -

Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: a Performance Guide

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Vander Wyst, Erin Elizabeth, "Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2754. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112202 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIMMO HAKOLA’S DIAMOND STREET AND LOCO: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst Bachelor of Fine Arts University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2007 Master of Music in Performance University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2009 -

Paul Anton Stadler

Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem 28. számú művészet- és művelődés- történeti tudományok besorolású doktori iskola PAUL ANTON STADLER (1753–1812) Egy gazdag művészi pálya tapasztalatainak összegzése a 18–19. század fordulóján SZITKA RUDOLF TÉMAVEZETŐ: PAPP MÁRTA DLA DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2012 I Tartalomjegyzék Tartalomjegyzék………………………………………………………….... I. Bevezető…………………………………………………………………..III. I. Fejezet. Hangszertörténeti áttekintés………………………………………………...1. A chalumeau…………………………………………………………...2. A klarinét kialakulása, építői és irodalma……………………………..5. II. Fejezet. Paul Anton Stadler, a klarinétvirtuóz…………………………………….....9. Két testvér egy szólamban (1753–1782)……………………………....9. Stadler és Mozart közös tíz éve (1781–1791)………………………..14. Esz-dúr szerenád (K. 375)……………………………………….15. Gran Partita (K. 361)…………………………………………….16. Esz-dúr trió (K. 498)……………………………………………..18. A-dúr klarinétkvintett (K. 581)…………………………………..20. Stadler európai körútja (1791–1796)…………………………………20. Aktív nyugdíjas évek: kevesebb koncert, több elméleti összegzés (1796–1812).…………....30. III. Fejezet. Theodor Lotz szerepe Anton Stadler művészi pályafutásában………........33. „Stadler klarinét vagy Lotz klarinét?”………………………………..33. A pozsonyi Batthyány zenekar……………………………………….34. A Lotz-féle hangszerek: klarinét…….……………………………….36. A basszetklarinét leírása korabeli dokumentumokban……………….38. A basszetkürt és a basszetklarinét dilemmája.………………………..45. Basszetkürtök alkalmazása Mozart műveiben………………………..47. Lotz basszetkürtjei…………………………………………………....49. Lotz hatása kortársaira………………………………………………..52. -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

The Earliest Music for Bass Clarinet Pdf

THE EARLIEST BASS CLARINET MUSIC (1794) AND THE BASS CLARINETS BY HEINRICH AND AUGUST GRENSER Albert R. Rice C.I.R.C.B. - International Bass Clarinet Research Center THE EARLIEST BASS CLARINET MUSIC (1794) AND THE BASS CLARINETS BY HEINRICH AND AUGUST GRENSER by Albert R. Rice For many years the bass clarinets by Heinrich Grenser and August Grenser made in 1793 and 1795 have been known. What has been overlooked is Patrik Vretblad’s list of a concert including the bass clarinet performed in 1794 by the Swedish clarinetist Johann Ignaz Strenensky.1 This is important news since it is the earliest documented bass clarinet music. All other textbooks and studies concerning the bass clarinet fail to mention this music played in Sweden. Although it is not definitely known what type of bass clarinet was played, evidence suggests that it was a bassoon-shaped bass clarinet by Heinrich Grenser. This article discusses the Stockholm court’s early employment of full time clarinetists; its players and music, including the bass clarinet works; the bass clarinets by Heinrich and August Grenser; and conclusions. Stockholm Court Orchestra Stockholm’s theater court orchestra employed seven clarinetists during the eighteenth century, including the famous composer and clarinetist Bernhard Henrik Crusell: Christian Traugott Schlick 1779-1786 August Heinrich Davidssohn 1779-1799 Georg Christian Thielemann 1785-1812 Carl Sigimund Gelhaar 1785-1793 Johann Ignaz Stranensky 1789-18052 Bernhard Henrik Crusell 1793-1834 Johan Christian Schatt 1798-18183 In 1779, Schlick and Davidssohn appeared as extra players at the Stockholm theater in a concert of the music academy. -

Klarinetistka Sabine Meyer

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra dechových nástrojů Hra na klarinet Klarinetistka Sabine Meyer Bakalářská práce Autor práce: Jiří Tolar DiS. Vedoucí práce: doc. MgA. Milan Polák Oponent práce: doc. MgA. Vít Spilka Brno 2015 Bibliografický záznam TOLAR, Jiří. Klarinetistka Sabine Meyer [Clarinetist Sabine Meyer]. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební fakulta, Katedra dechových nástrojů, 2015. 21 s. Vedoucí bakalářské práce doc. MgA. Milan Polák. Anotace Tato práce pojednává o klarinetistce Sabine Meyer. V práci je životopis Sabine Meyer, rozbor její interpretace a diskografie. Annotation This thesis deals with clarinetist Sabine Meyer. Thesis includes biography of Sabine Meyer, analysis of her interpretation and list of recordings. Klíčová slova Meyer, klarinet, nahrávka, interpretace, koncert, Stamic Keywords Meyer, clarinet, recording, interpretation, concert, Stamitz Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem předkládanou práci zpracoval samostatně a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. V Brně dne 10. května 2015 Jiří Tolar Obsah Úvod ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Životopis ............................................................................................................................... 2 2. Trio di Clarone ...................................................................................................................... 7 3. Bläserensemble Sabine Meyer .......................................................................................... -

(Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at Th

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Theodor Lotz A Biographical and Organological Study Melanie Piddocke PhD The University of Edinburgh 2011 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this work is original and has not been previously submitted in whole or part by me or any other person for any qualification or award. I further certify that due acknowledgement is given to the sources of information and ideas derived from the original scholarship of others, and that to the best of my ability all scholarly conventions and proprieties have been observed in the use, citation and documentation of these sources. (Signed) (Date) 26/06/2012 Abstract This dissertation is a comprehensive study of the life and work of the Viennese woodwind instrument maker Theodor Lotz. Lotz is central to many of the most significant developments in woodwind instrument manufacture and compositions of late 18th century Vienna, and is associated with some of the greatest players and composers of the day. -

Martin Frost

Vol. 46 • No. 4 September 2019 MARTIN FROST Caroline Schleicher-Krähmer: Hook or Lefèvre: Who Wrote The First Female Clarinet Soloist the Concerto in E-flat? Tom Martin and André Previn Performer’s Guide to Air Travel with a Bass Clarinet Dialogue de l’ombre double Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] hope everyone enjoyed a great summer. It was EDITORIAL BOARD wonderful to see so many members in Knoxville Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, at ClarinetFest®! We heard so many remarkable Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder performances by superb clarinet artists from around MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR Ithe world. I must once again thank Artistic Director Victor Gregory Barrett Chavez and the artistic leadership team for producing such [email protected] a memorable festival. Congratulations to the three new AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR ICA Honorary Members: Ron Odrich, Alan Stanek and Kip Franklin Eddy Vanoosthuyse. The ICA is also very grateful for the [email protected] generous support from all of the sponsors in Knoxville, Mitchell Estrin ASSOCIATE AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR including Buffet Crampon, D’Addario, Rovner Products, RZ Jeffrey O’Flynn Woodwinds, Henri Selmer Paris, Vandoren and Yamaha. Stay [email protected] tuned to the December issue for complete coverage of ClarinetFest® 2019. -

98967 Concilium Booklet.Indd

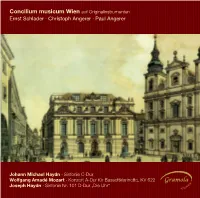

Concilium musicum Wien auf Originalinstrumenten Ernst Schlader · Christoph Angerer · Paul Angerer Johann Michael Haydn · Sinfonie C-Dur Wolfgang Amadé Mozart · Konzert A-Dur für Bassettklarinette, KV 622 Joseph Haydn · Sinfonie Nr. 101 D-Dur „Die Uhr“ 9989678967 CConciliumoncilium BBooklet.inddooklet.indd 1 003.12.20123.12.2012 112:52:232:52:23 Johann Michael Haydn (1737–1806) Symphony No. 39 in C major, Salzburg 1788 Sinfonie Nr. 39 C-Dur, Salzburg 1788 1 (I) Allegro con spirito 4:40 2 (II) Andante 2:23 3 (III) Finale-Fugato. Molto vivace 4:46 Wolfgang Amadé Mozart (1756–1791) Concerto in A major for Basset Clarinet, K 622, Vienna 1791 Konzert A-Dur für Bassettklarinette, KV 622, Wien 1791 4 (I) Allegro 11:33 5 (II) Adagio 6:04 6 (III) Rondo. Allegro 8:35 Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) Symphony No. 101 in D major “The Clock”, Vienna/London 1793/94 Sinfonie Nr. 101 D-Dur „Die Uhr“, Wien/London 1793/94 7 (I) Adagio – Presto 8:25 8 (II) Andante 7:42 9 (III) Menuetto. Allegro 6:52 bl (IV) Vivace 4:40 2 9989678967 CConciliumoncilium BBooklet.inddooklet.indd 2 003.12.20123.12.2012 112:52:452:52:45 Basset clarinet / Bassettklarinette Ernst Schlader Concertmaster / Konzertmeister Christoph Angerer Conductor / Dirigent Paul Angerer Concilium musicum Wien Transverse flute / Traversflöte Robert Pinkl, Gertraud Wimmer Oboe / Oboe Elisabeth Baumer, Birgit Heller-Meisenburg Bassoon / Fagott Klaus Hubmann, Katalin Sebella Natural horn / Horn Hermann Ebner, Andreas Hengl Clarion / Trompete Peter Weitzer, Gerald Preisl Timpani / Pauken Bernhard Winkler 1st Violin / 1. Violine Christoph Angerer, Iris Krall, Christoph Bitzinger, Wolfgang Augustin, Susanne Kührer-Degener, Christiane Bruckmann-Hiller 2nd Violin / 2. -

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 - 1791) REQUIEM & CLARINET CONCERTO Chœur de Chambre de Namur - New Century Baroque Leonardo García Alarcón Director Label Manager Editorial assistant Recorded in Recording Engineers Recording Producer, editing, mixing & mastering Cover photograph & design Director Booklet graphic design Label Manager Booklet photo credits Editorial assistant Printers Clarinet Concerto recording Requiem recording Recording Producer Cover photograph & design Booklet graphic design Booklet photo credits Printers WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 - 1791) 1 CLARINET CONCERTO IN A MAJOR K622 1 Allegro 12’36 2 Adagio 6’32 3 Rondo 8’52 REQUIEM IN D MINOR K626 4 Introitus: Requiem aeternam 4’43 5 Kyrie eleison 2’18 6 Dies irae 1’51 7 Tuba mirum 3’00 8 Rex tremendae majestatis 2’06 9 Recordare Jesu pie 5’03 10 Confutatis maledictis 2’08 2 11 Lacrimosa dies illa 2’46 12 Amen 1’36 13 Domine Jesu Christe 3’27 14 Versus: Hostias et preces 3’27 15 Communio: Lux aeterna cum sanctis tuis 5’14 TOTAL TIME 65’40 3 Julia Dagerfelt Flûtes Beatrice Scaldini Anne Freitag Leonardo García Alarcón direction Reynier Guerrero Marjorie Pfi ster Kinga Ujszaszi Cors de basset (Requiem) Violons II Benjamin Dieltjens Solistes Boris Begelman Francesco Spendolini Raphaëlle Pacault Andrea Vassalle Bassons Benjamin Dieltjens clarinette de basset Amie Weiss Zoë Matthews Carla Linné Anna Flumiani Lucy Hall soprano Angélique Noldus mezzo-soprano Altos Cors Hui Jin ténor Martine Schnorkh Alessandro Denabian Josef Wagner baryton-basse Joanne Miller Elisa Bognetti Marina -

5 September 2008 Page 1 of 38

Radio 3 Listings for 30 August – 5 September 2008 Page 1 of 38 SATURDAY 30 AUGUST 2008 Fauré, Gabriel (1845-1924) Nocturne No.6 in D flat major (Op.63) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00d3qy4) Jean-Yves Thibaudet (piano) With Jonathan Swain. Durante, Francesco (1684-1755) PLAYLIST: Concerto per quartetto no.6 in A major Leifs, Jón (1899-1968) Concerto Köln Galda Loftr, overture to "Loftr op. 10' Salzedo, Carlos (1885-1961) Elgar, Edward ((1857-1934) Variations sur un thème dans le style ancien (Op.30) Variations on an original theme ('Enigma') for orchestra (op. 36) Mojca Zlobko (harp) Rachmaninov, Sergey (1873-1943) Spohr, Louis (1784-1859) Piano Concerto no. 3 (Op. 30) in D minor Fantasie and variations on a theme of Danzi in B minor (Op.81) Vikingur Heidar Olafsson (piano), Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Joze Kotar (clarinet), Slovene Philharmonic String Quartet Rumon Gamba (conductor) Bach, Johann Christoph (1642-1703) Kaldalón, Sigvaldi (1881-1946) Motet : Fürchte dich nicht Ave Maria Cantus Cölln: Johanna Koslowsky (soprano), Graham Pushee Vikingur Heidar Olafsson (piano) (counter-tenor), Gerd Türk & Wilfred Jochens (tenors), Stephan Schreckenberger (bass), Christoph Anselm Noll (organ), Konrad Beethoven, Ludwig van (1770-1827) Junghänel (director) The Mount of Olives (Op.85) Olga Pasichny (soprano), Corby Welch (tenor), Marcus Matz, Rudolf (1901-1988) Niedermeyr (bass), Das Neue Orchester, Oslo Cathedral Choir, Ballade Christoph Spering (conductor) Zagreb Piano Trio Goldmark, Károly (1830-1915) Grundt, Albert (1840-1878) / Knoll, Johann