Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos - A survey of the major recordings by Ralph Moore Ariadne auf Naxos is less frequently encountered on stage than Der Rosenkavalier or Salome, but it is something of favourite among those who fancy themselves connoisseurs, insofar as its plot revolves around a conceit typical of Hofmannsthal’s libretti, whereby two worlds clash: the merits of populist entertainment, personified by characters from the burlesque Commedia dell’arte tradition enacting Viennese operetta, are uneasily juxtaposed with the claims of high art to elevate and refine the observer as embodied in the opera seria to be performed by another company of singers, its plot derived from classical myth. The tale of Ariadne’s desertion by Theseus is performed in the second half of the evening and is in effect an opera within an opera. The fun starts when the major-domo conveys the instructions from “the richest man in Vienna” that in order to save time and avoid delaying the fireworks, both entertainments must be performed simultaneously. Both genres are parodied and a further contrast is made between Zerbinetta’s pragmatic attitude towards love and life and Ariadne’s morbid, death-oriented idealism – “Todgeweihtes Herz!”, Tristan und Isolde-style. Strauss’ scoring is interesting and innovative; the orchestra numbers only forty or so players: strings and brass are reduced to chamber-music scale and the orchestration heavily weighted towards woodwind and percussion, with the result that it is far less grand and Romantic in scale than is usual in Strauss and a peculiarly spare ad spiky mood frequently prevails. -

Bach Festival the First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation

Bach Festival The First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 1921, 2013 THE 2013 BACH FESTIVAL IS MADE POSSIBLE BY: e Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil DEDICATION ELINORE LOUISE BARBER 1919-2013 e Eighty-rst Annual Bach Festival is respectfully dedicated to Elinore Barber, Director of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute from 1969-1998 and Editor of the journal BACH—both of which she helped to found. She served from 1969-1984 as Professor of Music History and Literature at what was then called Baldwin-Wallace College and as head of that department from 1980-1984. Before coming to Baldwin Wallace she was from 1944-1969 a Professor of Music at Hastings College, Coordinator of the Hastings College-wide Honors Program, and Curator of the Rinderspacher Rare Score and Instrument Collection located at that institution. Dr. Barber held a Ph.D. degree in Musicology from the University of Michigan. She also completed a Master’s degree at the Eastman School of Music and received a Bachelor’s degree with High Honors in Music and English Literature from Kansas Wesleyan University in 1941. In the fall of 1951 and again during the summer of 1954, she studied Bach’s works as a guest in the home of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Since 1978, her Schweitzer research brought Dr. Barber to the Schweitzer House archives (Gunsbach, France) many times. In 1953 the collection of Dr. Albert Riemenschneider was donated to the University by his wife, Selma. Sixteen years later, Dr. Warren Scharf, then director of the Conservatory, and Dr. -

Departamento De Filosofía

DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOSOFÍA APROXIMACIÓN AL LENGUAJE DE OLIVIER MESSIAEN: ANÁLISIS DE LA OBRA PARA PIANO VINGT REGARS SUR L’ENFANT - JESÚS FRANCISCO JAVIER COSTA CISCAR UNIVERSITAT DE VALENCIA Servei de Publicacions 2004 Aquesta Tesi Doctoral va ser presentada a Valencia el día 12 de Febrer de 2004 davant un tribunal format per: - D. Francisco José León Tello - D. Salvador Seguí Pérez - D. Antonio Notario Ruiz - D. Francisco Carlos Bueno Camejo - Dª. Carmen Alfaro Gómez Va ser dirigida per: D. Román De La Calle D. Luis Blanes ©Copyright: Servei de Publicacions Francisco Javier Costa Ciscar Depòsit legal: I.S.B.N.:84-370-5899-6 Edita: Universitat de València Servei de Publicacions C/ Artes Gráficas, 13 bajo 46010 València Spain Telèfon: 963864115 UNIVERSIDAD DE VALENCIA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACION AREA DE ESTETICA Y TEORIA DEL ARTE APROXIMACION AL LENGUAJE DE OLIVIER MESSIAEN: ANALISIS DE LA OBRA PARA PIANO VINGT REGARDS SUR L´ ENFANT - JESUS TESIS DOCTORAL REALIZADA POR: FRANCISCO JAVIER COSTA CISCAR DIRIGIDA POR LOS DOCTORES: DR. D. LUIS BLANES ARQUES DR. D. ROMAN DE LA CALLE VALENCIA 2003 I N D I C E 1.- Introducción ........................................................................ 5 2.- Antecedentes e influencias estilísticas en el lenguaje de Olivier Messiaen ........................................... 10 3.- Elementos musicales del lenguaje de Messiaen y su aplicación en la obra para piano Vingt Regards sur l ´ Enfant - Jésus ........................................................ 15 4.- Vingt Regards sur l ´ Enfant - Jésus : Datos Generales. Características de su escritura pianística .................. 42 5.- Temática, simbología e iconografía en Vingt Regards sur l ´ Enfant - Jésus ........................................................ 45 6.- Análisis Formal de la obra .......................................... 67 7.- Evolución de los Temas de la obra: Estudio comparativo de su desarrollo y presentación ........ -

Newsletter 2-2009

Newsletter 2 / 2009 Bock’s Music Shop Glasauergasse 14/3 1130 Wien (Europe) Tel.- u. Fax: (+43-1)877-89-58 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.bocksmusicshop.at Liebe Musik- und Buchfreunde! In dieser Ausgabe finden Sie folgende Themen: • 80. Geburtstag des Kammersängers Kurt Equiluz • Die erste Produktion unseres neu gegründeten CD-Labels Bock Productions • Die CDs des Monats aus den Bereichen JAZZ und KLASSIK. • Aktuelle CD- und DVD-Veröffentlichungen • Buch-Neuerscheinungen Kurt Equiluz – Tenor und Musiker Zum 80. Geburtstag (geb. 13. Juni 1929) Foto: Kurt Equiluz Copyright: D. Bock Selbstporträt Kurt Equiluz Ich wurde am 13. Juni 1929 in Wien geboren. Schon in frühen Jahren kündigte sich eine musikalische Begabung an. Als ich im Alter von zehn Jahren zu den Wiener Sängerknaben kam und dort bald auch solistische Aufgaben zu bewältigen hatte, war mein Weg für die Zukunft vor- programmiert. 1944 begann ich außerdem mit dem Studium der Harfe und der Musiktheorie an der Staatsakademie in Wien, 1946 kam das Gesangsstudium dazu, das ich bei Kammersänger Adolf Vogel absolvierte. Noch während des Studiums trat ich 1945 in den Akademie-Kammerchor unter der Leitung von Prof. Ferdinand Grossmann ein, der schon zuvor während meiner Knabenzeit künstlerischer Leiter der Wiener Sängerknaben war. BOCK'S MUSIC SHOP Seite 1 Newsletter 2 / 2009 1950 wurde ich an die Wiener Staatsoper engagiert, an der ich bis 1983 Ensemblemitglied gewesen bin. Dort feierte ich vor allem als Interpret der Tenor-Bufforollen große Erfolge; als Don Curzio in ‚Figaros Hochzeit‘ war ich allein 154mal, als Scaramuccio in ‚Ariadne auf Naxos‘ 123mal zu sehen. Obendrein gab ich den Balthasar Zorn in den ‚Meistersingern‘, den Spoletta in der ‚Tosca‘, den Monostatos in der ‚Zauberflöte‘ oder den Rossillon in der ‚Lus- tigen Witwe‘. -

Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: a Performance Guide

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Vander Wyst, Erin Elizabeth, "Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2754. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112202 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIMMO HAKOLA’S DIAMOND STREET AND LOCO: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst Bachelor of Fine Arts University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2007 Master of Music in Performance University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2009 -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Robin Fisher, DMA Soprano

Robin Fisher, DMA Soprano 730 Whitehall Way Sacramento, California 95864 Phone & FAX: 916 / 971-9607 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, Texas (08/98-08/01) . Doctor of Musical Arts (August 2001) GPA = 4.0 . Areas of Specialization: Vocal Performance, Vocal Pedagogy . Treatise: “The Writings and Art Songs of John Duke: 1917-1945” Vienna State Academy for Music & the Performing Arts: Vienna, Austria (9/86-1/90) . Diplom (January 1990) . Areas of Specialization: Vocal Performance, Art Song, Opera, Diction Hamburg State Academy of Music & the Performing Arts: Germany (9/83-7/86) . Areas of Study: Vocal Performance, Movement, Diction, Vocal Pedagogy Hamburg State University: Hamburg, Germany (9/83-7/85) . Areas of Study: Modern German History, Political Science . Research Paper: “Mitbestimmung and the German Labor Movement of the 1950s” Smith College: Northampton, Massachusetts (9/81-5/83) . Bachelor of Arts cum laude . Areas of Study: German Literature, European History . Phi Beta Kappa, Outstanding German Student San José State University: San Jose, California (9/79-6/81) . Major: Music (Vocal Performance) . Outstanding Fine Arts Student, 1981 TEACHING Assistant Professor of Voice: California State University, Sacramento (present) . Graduate & Undergraduate Applied Voice (MM, BM, BA) . Class Voice Assistant Professor of Voice, tenured: Baylor University, Waco, Texas (1995-2002) . Graduate & Undergraduate Applied Voice (MM, BM, BME, BA) . German, Italian, and English Diction Lecturer of Vocal -

The Historical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Theses Theses and Dissertations 5-15-2010 The iH storical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach Marva J. Watson Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Watson, Marva J., "The iH storical Figures of the Birthday Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach" (2010). Theses. Paper 157. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by Marva Jean Watson B.M., Southern Illinois University, 1980 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Degree School of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2010 THESIS APPROVAL THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH By Marva Jean Watson A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music History and Literature Approved by: Dr. Melissa Mackey, Chair Dr. Pamela Stover Dr. Douglas Worthen Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 2, 2010 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF MARVA JEAN WATSON, for the Master of Music degree in Music History and Literature, presented on 2 April 2010, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: THE HISTORICAL FIGURES OF THE BIRTHDAY CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

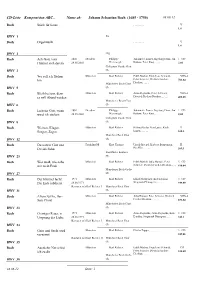

CD-Liste Komponisten ABC... Johann Sebastian Bach

1 CD 1 CD 3 CD 3 CD 848,08 VHS-A 693,02 848,1 3 CD 849,01 CD 810,09 V 1,4 V 1,4 2,01 VHS-A 703,02 VHS-A 400,05 2,02 V 105,3 H 269,1 3 CD 810,04 08.06.12 Elisabeth Speiser, Kurt Equiluz, Siegmund Nimsgern, , , , , , Julia Hamari, Schreier, Peter Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, , , , , , Anna Reynolds, Anna Reynolds, Kurt Equiluz, Siegmund Nimsgern, , , , , Hertha Töpper, , , , , , , , Edith Mathis, Schmidt, Trudeliese Schreier, Peter Dietrich Fischer- Dieskau, , , , , , , , , , , , , -- , , , , , , , , -- Danz,Johannette Jan Ingeborg Zomer, -- , Kooj, , Peter , , Kobow, Edith Mathis, Schmidt, Trudeliese -- Schreier, Peter Dietrich Fischer- Dieskau, , , , , Anna Schreier, Reynolds, Peter --Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, , , , , , Danz,Johannette Jan Ingeborg Zomer, -- , Kooj, , Peter , , Kobow, Kieth Lutze, HelmutGert Krebs, --Engen, , , , , , Ursula Buckel, Barbara Bornemann, -- Hoefflin, , , , , , Edith Mathis, Julia Hamari, Peter --Schreier, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, , , , , -- -- -- -- -- Philippe Herreweghe Philippe Herreweghe Richter Karl Richter Karl Karl Richter Karl Richter Karl Richter Karl -- -- -- Richter Karl -- Richter Karl -- -- Richter Karl -- Kurt Thomas -- Richter Karl -- -- -- -- -- -- a rg h h h h h h h h h h h h C Münchener Bach-Orche C Münchner Bach Chor C FrankfurterKantorei C Münchener Bach-Orche C C Münchener Bach-Chor C C K O Gent Collegium Vocale C Münchener Bach-Chor C Münchener Bach-Chor C Gent Collegium Vocale C Münchner Bach Chor Münchner Bach Chor Münchner Bach Chor Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750) München München -

Vienna « Singakademie » – Concerts Including Choral Works of Anton Bruckner (1888-2015)

Vienna « Singakademie » – Concerts including choral works of Anton Bruckner (1888-2015) Source : https://www.wienersingakademie.at/de/konzertarchiv/?archiv=composer&id=93 10 December 1888 « Großer-Musikvereins-Saal » , Vienna : Max von Weinzierl conducts the Vienna « Singakademie » Mixed-Choir. Soloists : Caroline Wogrincz (Soprano) , Josef Lamberg (Piano) . Johannes Brahms : « Fragen. Sehr lebhaft und rasch » (Asking) , Song in C major for women's choir, Opus 44, No. 4 (1859-1860) . Johannes Brahms : « Minnelied » (Song of Love) , Song in E major for women's choir, Opus 44, No. 1 (1859-1860) . Wilhelm Friedemann Bach : Chorus « Lasset uns ablegen die Werke der Finsternis » (F. 80) . Anton Bruckner : « Ave Maria » No. 2 ; Marian hymn in F major for 7-voice mixed unaccompanied choir (SAATTBB) (WAB 6) (1861) . Laurentius Lemlin : « Der Gutzgauch auf dem Zaune saß » , Folk-song for unaccompanied voices (1540) . Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina : « Missa Tu es Petrus » , Parody Mass for 6 mixed-voices (SSATBB) (IGP 110) . Carl Wilhelm Schauseil : « Mir ist ein schön’s braun’s Mägdelein » , folk-song. Franz Schubert : « Mirjams Siegesgesang » , Opus 136 (D. 942) . 13 May 1891 « Minoriten-Kirche » , Vienna. Max von Weinzierl conducts the Vienna « Singakademie » Mixed-Choir. Soloists : Sofie Chotek (Soprano) , Carl Führich (Organ) . Johann Sebastian Bach : « Welt, ade ! ich bin dein müde » (World, farewell ! I am weary of thee) , Chorale in B-flat major for 5-part mixed-choir (SSATB) and orchestra (BWV 27/6) (1726) . Anton Bruckner : « Ave Maria » No. 2 ; Marian hymn in F major for 7-voice mixed unaccompanied choir (SAATTBB) (WAB 6) (1861) . Hermannus Contractus (Herman the Cripple or Herman of Reichenau) : « Salve Regina » harmonized by Professor Franz Krenn. -

Klarinetistka Sabine Meyer

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra dechových nástrojů Hra na klarinet Klarinetistka Sabine Meyer Bakalářská práce Autor práce: Jiří Tolar DiS. Vedoucí práce: doc. MgA. Milan Polák Oponent práce: doc. MgA. Vít Spilka Brno 2015 Bibliografický záznam TOLAR, Jiří. Klarinetistka Sabine Meyer [Clarinetist Sabine Meyer]. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební fakulta, Katedra dechových nástrojů, 2015. 21 s. Vedoucí bakalářské práce doc. MgA. Milan Polák. Anotace Tato práce pojednává o klarinetistce Sabine Meyer. V práci je životopis Sabine Meyer, rozbor její interpretace a diskografie. Annotation This thesis deals with clarinetist Sabine Meyer. Thesis includes biography of Sabine Meyer, analysis of her interpretation and list of recordings. Klíčová slova Meyer, klarinet, nahrávka, interpretace, koncert, Stamic Keywords Meyer, clarinet, recording, interpretation, concert, Stamitz Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem předkládanou práci zpracoval samostatně a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. V Brně dne 10. května 2015 Jiří Tolar Obsah Úvod ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Životopis ............................................................................................................................... 2 2. Trio di Clarone ...................................................................................................................... 7 3. Bläserensemble Sabine Meyer ..........................................................................................