Downloaded by Users to Use As They See Fit on Any Platform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bab Ii Tinjauan Pustaka

BAB II TINJAUAN PUSTAKA A. DESKRIPSI SUBYEK PENELITIAN 1. SISTAR Sistar merupakan girlband yang berada di bawah naungan Starship Entertainment. Girlband yang debut pada tanggal 3 Juni 2010 ini beranggotakan Hyorin, Soyu, Bora, dan Dasom. Teaser debut Sistar yang berjudul Push Push rilis pada tanggal 1 Juni 2010, dan melakukan debut stage pertama kali di acara Music Bank (salah satu acara musik Korea Selatan) tanggal 4 Juni 2010 (http://www.starship- ent.com/index.php?mid=sistaralbum&page=2&document_srl=373, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 11.30 WIB). Gambar 2.1 Foto teaser debut Sistar berjudul Push Push Di tahun yang sama, tepatnya tanggal 25 Agustus, Sistar kembali mempromosikan single debut berjudul Shady Girl. Single ini semakin membuat nama Sistar dikenal oleh khalayak, dan menempati chart tinggi dibeberapa situs musik Korea Selatan. Tanggal 23 13 14 November, Sistar merilis Teaser MV untuk single baru berjudul How Dare You. Namun karena permasalahan perebutan perbatasan antara Korea Utara dan Korea Selatan, membuat MV untuk Single How Dare You sedikit terlambat dipublikasikan. Tepat seminggu, akhirnya pada tanggal 2 Desember MV tersebut rilis dan berhasil menempati urutan teratas di beberapa chart music seperti Melon, Mnet, Soribada, Bugs, Monkey3, dan Daum Musik. Dalam Melon Chart bulan Desember tahun 2010, Sistar menempati urutan ke empat dalam Top 100 (http://www.melon.com/chart/search/index.htm, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 12.25 WIB). Sistar - Single How Dare You Gambar 2.2 Melon Chart Desember 2010 Untuk tahun 2011, Sistar kembali melebarkan sayapnya di dunia musik dengan membentuk sub-unit yang beranggotakan Hyorin dan Bora. -

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

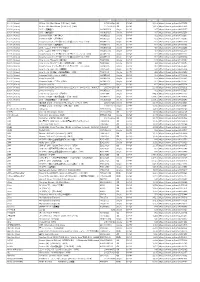

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

Access the Best in Music. a Digital Version of Every Issue, Featuring: Cover Stories

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MAY 28, 2020 Page 1 of 29 INSIDE Sukhinder Singh Cassidy • ‘More Is More’: Exits StubHub Amid Why Hip-Hop Stars Have Adopted The Restructuring, Job Cuts Instant Deluxe Edition BY DAVE BROOKS • Coronavirus Tracing Apps Are Editors note: This story has been updated with new they are either part of the go-forward organization Being Tested Around information about employees who have been previously or that their role has been impacted,” a source at the the World, But furloughed, including news that some will return to the company tells Billboard. “Those who are part of the Will Concerts Get Onboard? organization on June 1. go-forward organization return on Monday, June 1.” Sukhinder Singh Cassidy is exiting StubHub, As for her exit, Singh Cassidy said that she had been • How Spotify telling Billboard she is leaving her post as president planning to step down following the Viagogo acquisi- Is Focused on after two years running the world’s largest ticket tion and conclusion of the interim regulatory period — Playlisting More resale marketplace and overseeing the sale of the even though the sale closed, the two companies must Emerging Acts During the Pandemic EBay-owned company to Viagogo for $4 billion. Jill continue to act independently until U.K. leaders give Krimmel, StubHub GM of North America, will fill the the green light to operate as a single entity. • Guy Oseary role of president on an interim basis until the merger “The company doesn’t need two CEOs at either Stepping Away From is given regulatory approval by the U.K.’s Competition combined company,” she said. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 ->4-~ , & I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy o f the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefihe Wikst

POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefihe Wikstrom Ofelia Jarl Ortega Samlingen Valeria Graziano • Samira Elagoz Ellen Soderhult Edgar Schmitz Manuel Scheiwiller Alina Popa Antonia Rohwetter & Max Wallenhorst Danjel Andersson : R - i I- " Mette Edvardsen Marten Spdngberg (Eds.) % POST-DANCE Alice Chauchat Ana Vujanovic Andre Lepecki Jonathan Burrows Bojana Cvejic Bojana Kunst Charlotte Szasz Josefine Wikstrom Ofelia Jarl Ortega Samlingen Valeria Graziano Samira Elagoz Ellen Soderhult Edgar Schmitz Manuel Scheiwiller Alina Popa Antonia Rohwetter & Max Wallenhorst Danjel Andersson Mette Edvardsen Marten Spangberg (Eds.) Published by MDT 2017 Creative commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Edited by Danjel Andersson, Mette Edvarsdsen and Mirten Spingberg Designed by Jonas Williamson ISBN 978-91-983891-0-4 This book is supported by Cullbergbaletten and Life Long Burning, a cultural network, funded with support from the European Commission. CULLBERGBALETTEN Culture o BUNNTNG Contents Acknowledgement 9 Danjel Andersson I Had a Dream 13 Marten Spangberg Introduction 18 Alice Chauchat Generative Fictions, or How Dance May Teach Us Ethics 29 Ana Vujanovic A Late Night Theory of Post-Dance, a selfinterview 44 Andre Lepecki Choreography and Pornography 67 Jonathan Burrows Keynote address for the Postdance Conference in Stockholm 83 Bojana Cvejic Credo In Artem Imaginandi 101 Bojana Kunst Some Thoughts on the Labour of a Dancer 116 Charlotte Szasz Intersubjective -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Everything Began with the Movie Moulin Rouge (2001)

Introduction Everything began with the movie Moulin Rouge (2001). Since I was so obsessed with this hit film, I couldn’t but want to know more about this particular genre - musical films. Then I started to trace the history of this genre back to Hollywood’s classical musical films. It’s interesting that musical films have undergone several revivals and are usually regarded as the products of escapism. Watching those protagonists singing and dancing happily, the audience can daydream freely and forget about the cruel reality. What are the aesthetic artifices of this genre so enchanting that it always catches the eye of audience generation after generation? What kinds of ideal life do these musical films try to depict? Do they (musical films) merely escape from reality or, as a matter of fact, implicitly criticize the society? In regard to the musical films produced by Hollywood, what do they reflect the contemporary social, political or economic situations? To investigate these aspects, I start my research project on the Hollywood musical film genre from the 1950s (its Classical Period) to 2002. However, some people might wonder that among all those Hollywood movies, what is so special about the musical films that makes them distinguish from the other types of movies? On the one hand, the musical film genre indeed has several important contributions to the Hollywood industry, and its influence never wanes even until today. In need of specialty for musical film production, many talented professional dancers and singers thus get the chances to join in Hollywood and prove themselves as great actors (actresses), too. -

Teaser Memorandum

Teaser Memorandum The First Half of 2017 Investment Opportunities In Korea Table of Contents Important Notice ………………………………… 1 Key Summary ………………………………… 2 Expected Method of Investment Promotion …………………………… 3 Business Plan ………………………………… 4 Business Introduct ………………………………… 5 License ………………………………… 11 Capacity ………………………………… 12 Market ………………………………… 13 Financial Figures ………………………………… 14 Key Summary Private & Confidential Investment Highlights RBW is a K-POP (Hallyu) contents production company founded by producer/songwriter Kim Do Hoon, Kim Jin Woo, and Hwang Sung Jin, who have produced numerous K-POP artists such as CNBLUE, Whee-sung, Park Shin Hye, GEEKS, 4MINUTE etc. Based on the “RBW Artist Incubating System’, the company researches and provides various K-POP related products such as OEM Artist & Music Production (Domestic/Overseas), Exclusive Artist Production (MAMAMOO, Basick, Yangpa etc.), Overseas Broadcasting Program Planning & Production (New concept music game show/Format name: RE:BIRTH), and K-POP Educational Training Program. With its business ability, RBW is currently making a collaboration with various domestic and overseas companies, including POSCO, NHN, Human Resources Development Service of Korea, Ministry of Labor & Employment, and KOTRA. • Business with RBW’s Unique Artist Incubating •Affiliation Relationship with International Key Factors System Companies Description • With analyzing the artists’ potentials and market trend, every stage for training and debuting artists (casting, training, producing, and album production) is efficiently processed under this system. Pictures Company Profiles Category Description Establishment Date 2013. 8. 26 Revenue 12 Billion Won (12 Million $) (2016) Website www.rbbridge.com Current Shareholder C.E.O. Kim Jin Woo 29.2%, C.E.O. Kim Do Hoon 29.2%, Institutional Investment 31.7%, Executives and Staff Composition 5.6%, Etc. -

• Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet • Consectetur Adipisicing Elit • Sed

Beeld en Geluid • Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet • Consectetur adipisicing elit • Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore • Et dolore magna aliqua Hooked on Music John Ashley Burgoyne Music Cognition Group Institute for Logic, Language and Computation University of Amsterdam Hooked on Music John Ashley Burgoyne · Jan Van Balen Dimitrios Bountouridis · Daniel Müllensiefen Frans Wiering · Remco C. Veltkamp · Henkjan Honing and thanks to Fleur Bouwer · Maarten Brinkerink · Aline Honingh · Berit Janssen · Richard Jong !emistoklis Karavellas · Vincent Koops · Laura Koppenburg · Leendert van Maanen Han van der Maas · Tobin May · Jaap Murre · Marieke Navin · Erinma Ochu Johan Oomen · Carlos Vaquero · Bastiaan van der Weij ‘Henry’ Dan Cohen & Michael Rossato-Benne" · 2014 · Alive Inside Long-term Musical Salience salience · the absolute ‘noticeability’ of something • cf. distinctiveness (relative salience) musical · what makes a bit of music stand out long-term · what makes a bit of music stand out so much that it remains stored in long-term memory Cascading Reminiscence Bumps 2063 a Listeners Listeners Born Age 20 Years 10 9 8 7 6 Personal Memories 5 Quality Rating 4 3 2 1 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 5-Year Period Parents Parents ReminiscenceBorn Age 20 Years Bumps b Listeners Listeners Born Age 20 Years 10 9 8 Personal Memories 7 6 Recognize 5 Like Rating 4 3 2 1 • critical period ages 15–25 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 5-Year Period • multi-generational Parents Parents Born Age 20 Years • parents and grandparents Fig. 2. Mean rating of the extent to which participants had personal memories associated with the songs of each 5-year period, together with (a) the judged quality of the songs and (b) whether participants liked and recognized the songs (after the percentage recognized was converted to the number of songs recognized). -

K-Pop: South Korea and International Relations S1840797

Eliana Maria Pia Satriano [email protected] s1840797 Word count: 12534 Title: K-pop: South Korea and International Relations s1840797 Table of Contents: 1. Chapter 1 K-pop and International Relations………………………………..……..…..3-12 1.1 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………..…..3-5 1.2 K-pop: from the National to the International Market: The History of K-pop………5-6 1.3 The Drivers Behind the K-pop Industry..………………………………….….….…6-10 1.4 The Involvement of the South Korean Government with Cultural Industries.…… 10-12 2. Chapter 2 Soft Power and Diplomacy, Music and Politics ……………………………13-17 2.1 The Interaction of Culture and Politics: Soft Power and Diplomacy………………13-15 2.2 Music and Politics - K-pop and Politics……………………………………………15-17 3. Chapter 3 Methodology and the Case Study of BTS……………………………..……18-22 3.1 Methodology………………………………………………………………….……18-19 3.2 K-Pop and BTS……………………………………………………………….……19-20 3.3 Who is BTS?………………………………………………………………….……20-22 3.4 BTS - Beyond Korea……………………………………………………………….…22 4. Chapter 4 Analysis ……………………………………………………….…….…….. 23-38 4.1 One Dream One Korea and Inter-Korea Summit……….…………………..……..23-27 4.2 BTS - Love Myself and Generation Unlimited Campaign…………………….…..27-32 4.3 Korea -France Friendship Concert..………………………………………..….…..33-35 4.4 Award of Cultural Merit…………………………………………….………….…..35-37 4.5 Discussion and Conclusion…………………………………………………….…..37-38 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………….….39-47 !2 s1840797 CHAPTER 1: K-pop and International Relations (Seventeen 2017) 1.1 Introduction: South Korea, despite its problematic past, has undergone a fast development in the past decades and is now regarded as one of the most developed nations. A large part of its development comes from the growth of Korean popular culture, mostly known as Hallyu (Korean Wave). -

WASTE PAPER Colleaion a NEW HOME?

. t v C » A s ^ c m n cr. xuHB 11. i n t t!40B TWELVE jKanrh^etrr Etintitts if^roUi D ll^ !l*l Pl6m 1 " i- there Is some danger thet flee, ■us to the stoeu auaagers. We w cosm ■ '" thrown helter-okelter e t nupOels, know they will M eay ooo- Green School 5509 About Town sMgkt egrout eU over churob Btruetlva ertUelem oCfered. Heard Along Main Street Uwan. Wild rise being eown In ARMY AND NAVY CLUB MMlt pleeoo n d i^ t net bo mgerdod “Besrfi AMag” really did hear t k i n a <Man «m koU thatr Gives Program C ky o f V V o f Chmrm And on Soma of Manehe$Ut^» Stdo SfrM fg, Too an the best thing. They b m tried the other day thet the new bus c a m «a H a f Uila afUmeoB Bt R with oets bofore, end It has not loop scbedulea from Hartford to tbt OBiiiiinrtrT- A buffet lunch Manchester Green vie Mein and proven popular. i i t e * ru g s m MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JI7NE 14, 1948 fFOURTBEN PAGES) P R IC tfO U ti trtn be eerred et three o’clock end A mother of two children celled » stope, were pussled by the deerth This buslneas o f adapting e crop Woodbridge etreeta. namely bueee Kindergarten and See> NEW SUPER VOL. Lxvn ., NO; u end epeghetti eupper et heeding out to the Green end re in to regloUr her obJecUon to of custonsere to n ktonUty has us pretty well ond Grade Pkeaent Children’s Dey progrems in the Let us look beck.