Registration Test Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles and Books About Western and Some of Central Nsw

Rusheen’s Website: www.rusheensweb.com ARTICLES AND BOOKS ABOUT WESTERN AND SOME OF CENTRAL NSW. RUSHEEN CRAIG October 2012. Last updated: 20 March 2013 Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig Using the information from this document: Please note that the research on this web site is freely provided for personal use only. Site users have the author's permission to utilise this information in personal research, but any use of information and/or data in part or in full for republication in any printed or electronic format (regardless of commercial, non-commercial and/or academic purpose) must be attributed in full to Rusheen Craig. All rights reserved by Rusheen Craig. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Wentworth Combined Land Sales Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig 1 Contents THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE WESTERN PLAINS. ...................................................... 6 Exploration of the Bogan. ................................................................................................................................... 6 Roderick Mitchell on the Darling. ...................................................................................................................... 7 Exploration of the Country between the Lachlan and the Darling ...................................................................... 7 Occupation of the Country. ................................................................................................................................ 8 Occupation -

Artesian Wells As a Means of Water Supply

m ^'7^ ^'^^ Cornell University Library TD 410.C88 Artesian wells as a means of water suppi 3 1924 004 406 827 (fimntW Winivmii^ Jibing BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcntg W. Sage X891 .JJJA ^ 'i-JtERliNC Llfif-^RV s Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924004406827 ARTESIAN WELLS. ARTESIAN WELLS As a Means of Water Supply, including an account of The Rise, Progress, and Present State of the Art of Boring FOR Water in Europe, Asia and America ; Progress in the Australian Colonies ; A Treatise on the Water-bearing Rocks ; Permanence OF Supplies ; The Most Approved Machinery for, and the Cost of Boring, WITH Form of Contract, etc. ; Treatise on Irrigation from Artesian Wells ; AND ON Sub-artesian or Shallow Boring, etc. WALTER GIBBONS COX, C.E., ASSOC. INST. C.E.'S, LONDON, 1869. PRICE, SEVEN SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE. BRISBANE, SYDNEY, MELBOURNE, AND ADELAIDE. Published by Sapsford & Co,, Adelaide Street, Brisbane. Sep., iSqs- 1895, DEDICATED BY PERMISSION TO MY ESTEEMED AND EARLIEST PATRON IN QUEENSLAND, Sir THOMAS M'lLWRAITH, C.E., K.C.M.G. LATE PREMIER OF QUEENSLAND. — PREFACE A First edition of this Book entitled, " On Artesian WeDs as a Means of Water Supply for Country Districts," was published in Brisbane in 1883. It was based upon papers published for me in the Leader newspaper, Melbourne, in 1878, one year before the first Artesian Bore was made in Australia— that at Kallara Station, New South Wales, in 1879, and two years before what is claimed to be the first artesian bore made in Australia—that at Sale, in Victoria—was commenced, advocating the utilisation of artesian supplies in this country. -

Cunninghamia : a Journal of Plant Ecology for Eastern Australia

Westbrooke et al., Vegetation of Peery Lake area, western NSW 111 The vegetation of Peery Lake area, Paroo-Darling National Park, western New South Wales M. Westbrooke, J. Leversha, M. Gibson, M. O’Keefe, R. Milne, S. Gowans, C. Harding and K. Callister Centre for Environmental Management, University of Ballarat, PO Box 663 Ballarat, Victoria 3353, AUSTRALIA Abstract: The vegetation of Peery Lake area, Paroo-Darling National Park (32°18’–32°40’S, 142°10’–142°25’E) in north western New South Wales was assessed using intensive quadrat sampling and mapped using extensive ground truthing and interpretation of aerial photograph and Landsat Thematic Mapper satellite images. 378 species of vascular plants were recorded from this survey from 66 families. Species recorded from previous studies but not noted in the present study have been added to give a total of 424 vascular plant species for the Park including 55 (13%) exotic species. Twenty vegetation communities were identified and mapped, the most widespread being Acacia aneura tall shrubland/tall open-shrubland, Eremophila/Dodonaea/Acacia open shrubland and Maireana pyramidata low open shrubland. One hundred and fifty years of pastoral use has impacted on many of these communities. Cunninghamia (2003) 8(1): 111–128 Introduction Elder and Waite held the Momba pastoral lease from early 1870 (Heathcote 1965). In 1889 it was reported that Momba Peery Lake area of Paroo–Darling National Park (32°18’– was overrun by kangaroos (Heathcote 1965). About this time 32°40’S, 142°10’–142°25’E) is located in north western New a party of shooters found opal in the sandstone hills and by South Wales (NSW) 110 km north east of Broken Hill the 1890s White Cliffs township was established (Hardy (Figure 1). -

Indexes to Correspondence Relating to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the Records

Indexes to correspondence relating to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the records of the Colonial Secretary’s Office and the Home Secretary’s Office 1896 – 1903. Queensland State Archives Item ID 6820 88/4149 (this top letter is missing) Letter number: 88/328 Microfilm Z1604, Microfilm frame numbers 3-4 contain a copy of the original letter. The original is contained on frames 5-6. Letter from the Reverend GJ Richner on behalf of the Committee for the Lutheran Mission of South Australia. He acknowledges receipt of the Colonial Secretary's letter advising that CA Meyer and FG Pfalser have been appointed trustees of Bloomfield River Mission Station (Wujal Wujal). He also asks for government support for both Bloomfield River and Cape Bedford Mission stations. He suggests that "It is really too much for the Mission Societies to spend the collections of poor Christians for to feed the natives". A note on letter 88/328 advises "10 pounds per month for 12 months". Queensland State Archives Item ID 6820 88/4149 (this top letter is missing) Letter number: 88/4058 Microfilm Z1604, Microfilm frame numbers 8-9 contain a copy of the original letter. (The original is contained on frames 10-11). Letter from the Reverend GJ Richner thanking the Colonial Secretary for the allowance of 10 pounds per month for Cape Bedford and Bloomfield River Mission Stations. He suggests, however, that the 10 pounds is "fully required" for the Cape Bedford Mission Station and asks for further funding to support Bloomfield River Mission Station. Queensland State Archives Item ID 6820 88/9301 (this top letter is missing) Letter number: 87/7064 Microfilm Z1604, Microfilm frame numbers 14-15. -

Queensland Parks (Australia) Sunmap Regional Map Abercorn J7 Byfield H7 Fairyland K7 Kingaroy K7 Mungindi L6 Tannum Sands H7

140° 142° Oriomo 144° 146° 148° 150° 152° Morehead 12Bensbach 3 4 5 6 78 INDONESIA River River Jari Island River Index to Towns and Localities PAPUA R NEW GUINEA Strachan Island Daru Island Bobo Island Bramble Cay A Burrum Heads J8 F Kin Kin K8 Mungeranie Roadhouse L1 Tangorin G4 Queensland Parks (Australia) Sunmap Regional Map Abercorn J7 Byfield H7 Fairyland K7 Kingaroy K7 Mungindi L6 Tannum Sands H7 and Pahoturi Abergowrie F4 Byrnestown J7 Feluga E4 Kingfisher Bay J8 Mungungo J7 Tansey K8 Bligh Entrance Acland K7 Byron Bay L8 Fernlees H6 Kingsborough E4 Muralug B3 Tara K7 Wildlife Service Adavale J4 C Finch Hatton G6 Koah E4 Murgon K7 Taroom J6 Boigu Island Agnes Waters J7 Caboolture K8 Foleyvale H6 Kogan K7 Murwillumbah L8 Tarzali E4 Kawa Island Kaumag Island Airlie Beach G6 Cairns E4 Forrest Beach F5 Kokotungo J7 Musgrave Roadhouse D3 Tenterfield L8 Alexandra Headland K8 Calcifer E4 Forsayth F3 Koombooloomba E4 Mutarnee F5 Tewantin K8 Popular national parks Mata Kawa Island Dauan Island Channel A Saibai Island Allora L7 Calen G6 G Koumala G6 Mutchilba E4 Texas L7 with facilities Stephens Almaden E4 Callide J7 Gatton K8 Kowanyama D2 Muttaburra H4 Thallon L6 A Deliverance Island Island Aloomba E4 Calliope J7 Gayndah J7 Kumbarilla K7 N Thane L7 Reefs Portlock Reef (Australia) Turnagain Island Darnley Alpha H5 Caloundra K8 Georgetown F3 Kumbia K7 Nagoorin J7 Thangool J7 Map index World Heritage Information centre on site Toilets Water on tap Picnic areas Camping Caravan or trailer sites Showers Easy, short walks Harder or longer walks -

Conrick of Nappa Merrie H. M. Tolcher

Conrick of Nappa Merrie - Revisited 07/12/2015 CONRICK OF NAPPA MERRIE A PIONEER OF COOPER CREEK BY H. M. TOLCHER 1997 i Conrick of Nappa Merrie - Revisited Published by Ian J. Itter Swan Hill Victoria 3585 Australia ISBN, Title: Conrick of Nappa Merrie - Revisited Transcribed by Ian J. Itter 2015 Postage Weight 1 Kg Classifications:- Pioneers – Australia ii Conrick of Nappa Merrie - Revisited © Helen Mary Forbes Tolcher, 1997 All rights reserved This book is copyright, other than for the purposes and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act, 1968 No part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher ISBN 0-646-32608-2 Printed on acid free, archival paper by Fast Books (A division of Wild & Woolley Pty. Ltd.) NSW, Australia iii Conrick of Nappa Merrie - Revisited TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ……………………………… v. Preface …………………………………………… vii. Map 1 ……….……………………………………. viii Map 2 ……….……………………………………. ix 1. The Irish Emigrant ……………………………….. 1 2. Droving to Queensland …………………………... 10 3. Selecting the Land ……………………………….. 16 4. A Journey to Charleville …………………………. 21 5. Settling at Nappa Merrie .……….……………….. 26 6. Exploration ..……………………………………... 33 7. Down the Strzelecki ..……………………………. 38 8. Back to Tower Hill ..…………………………….. 42 9. Cooper Creek Concerns .…………………………. 45 10. Business in Melbourne …………………………… 57 11. New Neighbours …..……………………………... 62 12. Letters to Agnes Ware .…………………………… 65 13. Wedded Bliss ……………………………………… 69 14. The Family Man …………………………………… 76 15. Difficulties and Disasters ………………………….. 84 16. Prosperity …………………………………………… 94 17. The Younger Generation ……………………………. 102 18. Retirement ...………………………………………… 110 19. -

1900 Miscellaneous Land Tenure in Western and Some of Central NSW Mentioned in the 1900 Government Gazette

Rusheen’s Website: www.rusheensweb.com 1900 Miscellaneous Land Tenure in Western and Some of Central NSW mentioned in the 1900 Government Gazette RUSHEEN CRAIG January 2012 Last updated: 4 November 2012 Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig Using the information from this document: Please note that the research on this web site is freely provided for personal use only. Site users have the author's permission to utilise this information in personal research, but any use of information and/or data in part or in full for republication in any printed or electronic format (regardless of commercial, non-commercial and/or academic purpose) must be attributed in full to Rusheen Craig. All rights reserved by Rusheen Craig. Miscellaneous Land Tenure Copyright © 2012, Rusheen Craig 1 of 240 Holder Lease Type and Qualification/Location/(Purpose) Area (Acres) Rental or No of Papers Type of Action Number Price (See Legend) £-s-d ABBOTT Louisa After Auction Sold at Corowa.LD & Psh-Mulwala. Co-Denison.Lot 5.Sec 39 …. …. 98-16210 Annulled Purchase a'BECKETT W.C. and a'BECKETT M.E. Preferential No 177; "Nelgowrie"; Central Division. 14,807 …. Occ1900-6564 PrOccL Granted Occupation License aBECKETT William Channing and POccL 177A Central Division. "Nelgowrie". 14,807 115-13-9 …. Pref Occupation aBECKETT Marsham Elwin License. A'BECKETT William Channing and OccL 177 Central Division. "Nelgowrie". 1,010 7-17-10 …. Renewal of Marsham Elwin Occupation License for 1901 ABERNETHY Harold CP 94-1 LD-Wellington.Psh-Guroba.Sec 42. Port 8. 40 …. 98-4768 Certificate of Conformity ABERNETHY Harold CP 95-9 LD-Wellington.Psh-Guroba.Sec 42. -

Development of a Learner's Grammar for Paakantyi

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright ! Development!of!a!Learner’s! Grammar!for!Paakantyi! ! Elena!Handlos!Andersen! ! A"thesis"submitted"in"fulfilment"of"the"requirements"for"the"degree"of" Master"of"Arts"(Research)" " " " School!of!Linguistics,!Faculty!of!Arts!and!Social!Sciences! The!University!of!Sydney! 2015! ! ! Acknowledgements! " First"and"foremost,"I"would"like"to"thank"the"Paakantyi"community"for"allowing"me"to"compile"the" -

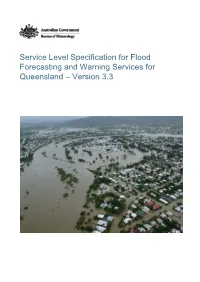

Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland – Version 3.3

Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland – Version 3.3 This document outlines the Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services provided by the Commonwealth of Australia through the Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology for the State of Queensland in consultation with the Queensland Flood Warning Consultative Committee Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland Published by the Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 (03) 9669 4000 www.bom.gov.au With the exception of logos, this guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Australia Attribution Licence. The terms and conditions of the licence are at www.creativecommons.org.au © Commonwealth of Australia (Bureau of Meteorology) 2021 Cover image: Aerial photo looking south over Rosslea during the Townsville February 2019 flood event. (Photograph courtesy of the Australian Defence Force). Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 2 Flood Warning Consultative Committee .......................................................................... 4 3 Bureau flood forecasting and warning services ............................................................... 5 4 Level of service and performance reporting .................................................................. -

Draft 30 July 2011 SIR SIDNEY KIDMAN

Draft 30 July 2011 SIR SIDNEY KIDMAN: AUSTRALIA’S CATLE KING AS PIONEER OF ADAPTATION TO CLIMATIC UNCERTAINTY Leo Dobes1 Abstract There is little direct evidence about the business model used by the legendary cattle king, Sir Sidney Kidman. Kidman‟s properties were generally contiguous, forming chains that straddled stock routes and watercourses in the most arid zone of central Australia, were invariably stocked at less than full capacity; providing access to the main capital city markets via railways, as well as a wealth of information on competing cattle movements. This combination of features effectively afforded strategic flexibility in the form of so-called „real options‟, especially during severe drought events. Alternative explanations such as the vertical integration of Kidman‟s operations, and spatial diversification of land holdings, offer only partial insights at best. Faced with a highly variable and unpredictable climate, combined with erosion and the spread of rabbits, Kidman provides a highly pertinent example of successful human adaptation to exogenous shocks such as climate change by avoiding expensive deterministic responses. Key words: climate change, adaptation, real options, drought, rangelands Introduction Sir Sidney Kidman (1857-1935) was a controversial figure. Born in modest circumstances in Adelaide, he eventually came to control, both directly and indirectly, a vast pastoral empire that stretched north-south across the rangelands of central and northern Australia, with further holdings in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Feted in England as a fabulously wealthy Cattle King, he also attracted criticism in Australia for trying to recruit London omnibus drivers as stockmen. During World War I, he made a name for himself nationally by donating fighter planes and other equipment to the armed forces. -

Dayle Green' and Libby Connors2

Dayle Green' and Libby Connors 2 EXPLORING THE BASIN Rich Pastures and Five years later Surveyor General The Darling River Basin had been Promised Lands John Oxley set offwith Evans to occupied by Aborigines for 30 000 George Evans became the first known determine where the western flowing years before the new white colonists European to look upon the rivers and Macquarie River might lead. But the pushed their way over the mountains plains ofthe Darling Basin. In river would not give up it's secret and into the outback. For the clans November 1813 Evans descended easily-Oxley was defeated by the that inhabited the Basin, the Darling from the Blue Mountains into the flooded reedbeds and endless was mapped out in stories and songs .valley ofthe Fish River, and explored channels ofthe Macquarie Marshes. that described the rivers and the the upper reaches ofthe Macquarie Unable to find their way through the """'.;l countryside. For the Europeans, the Valley. He returned with a diary full marshes, Oxley and Evans turned east ~... ...., ~24 geography ofthe Basin was a ofglowing descriptions-a promised and discovered the Liverpool Plains, perplexing jigsaw puzzle that took land ofJush pastures, rich soils and another fertile area with great over fifty years to complete. The park-like woodlands. The promise of agricultural promise. framework of the river system that such rich rewards ensured that within By 1824, British colonisation to made up this vast inland Basin was a year of Evans' return the first road the south of Sydney had reached the mapped out by the government over the mountains had been southern coastline ofthe continent appointed explorers who set off constructed. -

National Arrangements for Flood Forecasting and Warning (Bureau of Meteorology, 2015)1

Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland – Version 2.0 This document outlines the Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services provided by the Commonwealth of Australia through the Bureau of Meteorology for the State of Queensland in consultation with the Queensland Flood Warning Consultative Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland Published by the Bureau of Meteorology GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 (03) 9669 4000 www.bom.gov.au With the exception of logos, this guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Australia Attribution Licence. The terms and conditions of the licence are at www.creativecommons.org.au © Commonwealth of Australia (Bureau of Meteorology) 2013. Cover image: Moderate flooding on the Fitzroy River at Yaamba, March 2012 | photograph by the Bureau of Meteorology. Service Level Specification for Flood Forecasting and Warning Services for Queensland Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 2 Flood Warning Consultative Committee .......................................................................... 4 3 Bureau flood forecasting and warning services ............................................................... 5 4 Level of service and performance reporting ..................................................................