The Thematic and Narrative Features of Jeet Thayil's Narcopolis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIAN POETRY – 20 Century Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D

th INDIAN POETRY – 20 Century Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. Part I : Early 20th Century Part II : Late 20th Century Early 20th Century Poetry Overview Poetry, the oldest, most entrenched and most respected genre in Indian literary tradition, had survived the challenges of the nineteenth century almost intact. Colonialism and Christianity did not substantially alter the writing of poetry, but the modernism of the early twentieth century did. We could say that Indian poetry in most languages reached modernity through two stages: first romanticism and then nationalism. Urdu, however, was something of an exception to this generalisation, in as much as its modernity was implicated in a romantic nostalgia for the past. Urdu Mohammad Iqbal Mohammad Iqbal (1877?-1938) was the last major Persian poet of South Asia and the most important Urdu poet of the twentieth century. A philosopher and politician, as well, he is considered the spiritual founder of Pakistan. His finely worked poems combine a glorification of the past, Sufi mysticism and passionate anti-imperialism. As an advocate of pan-Islam, at first he wrote in Persian (two important poems being ‗Shikwah,‘ 1909, and ‗Jawab-e-Shikwah,‘ 1912), but then switched to Urdu, with Bangri-Dara in 1924. In much of his later work, there is a tension between the mystical and the political, the two impulses that drove Urdu poetry in this period. Progressives The political came to dominate in the next phase of Urdu poetry, from the 1930s, when several poets formed what is called the ‗progressive movement.‘ Loosely connected, they nevertheless shared a tendency to favour social engagement over formal aesthetics. -

Contemporary Indian English Fiction Sanju Thoma

Ambedkar University Delhi Course Outline Monsoon Semester (August-December 2018) School: School of Letters Programme with title: MA English Semester to which offered: (II/ IV) Semester I and III Course Title: Contemporary Indian English Fiction Credits: 4 Credits Course Code: SOL2EN304 Type of Course: Compulsory No Cohort MA English Elective Yes Cohort MA other than English For SUS only (Mark an X for as many as appropriate): 1. Foundation (Compulsory) 2. Foundation (Elective) 3. Discipline (Compulsory) 4. Discipline (Elective) 5. Elective Course Coordinator and Team: Sanju Thomas Email of course coordinator: [email protected] Pre-requisites: None Aim: Indian English fiction has undeniably attained a grand stature among the literatures of the world. The post-Salman Rushdie era has brought in so much of commercial and critical success to Indian English fiction that it has spurred great ambition and prolific literary activities, with many Indians aspiring to write English fiction! Outside India, Indian English fiction is taken as representative writings from India, though at home the ‘Indianness’ of Indian English fiction is almost always questioned. A course in contemporary Indian English fiction will briefly review the history of Indian English fiction tracing it from its colonial origins to the postcolonial times to look at the latest trends, and how they paint the larger picture of India. Themes of nation, culture, politics, identity and gender will be taken up for in-depth analysis and discussions through representative texts. The aim will also be to understand and assess the cross-cultural impact of these writings. Brief description of modules/ Main modules: Module 1: What is Indian English Fiction? This module takes the students through a brief history of Indian English fiction, and also attempts to problematize the concept of Indian English fiction. -

Vedanta and Cosmopolitanism in Contemporary Indian Poetry Subhasis Chattopadhyay

Vedanta and Cosmopolitanism in Contemporary Indian Poetry Subhasis Chattopadhyay illiam blake (1757–1827) burnt I have felt abandoned … into W B Yeats (1865–1939). A E I discovered pettiness in a gloating vaunting WHousman (1859–1936) absorbed both Of the past that had been predatory4 Blake and Yeats: The line ‘When I walked down meandering On the idle hill of summer, roads’ echoes Robert Louis Stevenson’s (1850– Sleepy with the flow of streams, 94) The Vagabond. Further glossing or annotation Far I hear the steady drummer of Fraser’s poems are not needed here and will Drumming like a noise in dreams … Far the calling bugles hollo, be done in a complete annotated edition of her High the screaming fife replies, poems by this author. The glossing or annotation Gay the files of scarlet follow: proves her absorption of literary influences, which Woman bore me, I will rise.1 she may herself not be aware of. A poet who does The dream-nature of all reality is important not suffer theanxiety of influence of great poets to note. This is Vedanta. True poetry reaffirms before her or him is not worth annotating. the truths of Vedanta from which arises cos- In ‘From Salisbury Crags’,5 she weaves myths mopolitanism. Neither the Cynics nor Martha as did Blake and Yeats before her.6 Housman too Nussbaum invented cosmopolitanism. This de- wove myths into his poetry. scription of hills and vales abound in Yeats’s2 and Mastery of imagery is essential for any poet. Housman’s poetry. Pride in being resilient is seen Poets may have agendas to grind. -

International Journal of the Frontiers of English Literature and the Patterns of ELT ISSN : 2320 - 2505

International Journal of The Frontiers of English Literature and The Patterns of ELT ISSN : 2320 - 2505 1 Page January 2013 www.englishjournal.mgit.ac.in Volume I, Issue 1 International Journal of The Frontiers of English Literature and The Patterns of ELT ISSN : 2320 - 2505 Another One Bites the Dark: Reading Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis as a Continuum of Aravind Adiga’s Dark India Exploration K. Koteshwar Research Scholar The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. e-mail : [email protected] Jeet Thayil’s first novel, Narcopolis is set mostly in Bombay in the 70s and 80s, and sets out to tell the city's secret history, when opium gave way to new cheap heroin. Thayil has said, he wrote the novel, “to create a kind of memorial, to inscribe certain names in stone”. As one of the characters (in Narcopolis) says, “it is only by repeating the names of the dead that we honor them. I wanted to honor the people I knew in the opium dens, the marginalized, the addicted and deranged, people who are routinely called the lowest of the low; and I wanted to make some record of a world that no longer exists, except within the pages of a book.” he told the Indian newspaper, The Hindu, that he had been an alcoholic (like many of the Bombay poets) and an addict for almost two decades: "I spent most of that time sitting in bars, getting very drunk, talking about writers and writing, and never writing. It was a colossal waste. I feel very fortunate that I got a second chance." Thayil has been writing poetry since his adolescence, paying careful attention to form. -

Indian English Novel After 1980: Encompassing the New Generation

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 8, Issue 1, 2021 INDIAN ENGLISH NOVEL AFTER 1980: ENCOMPASSING THE NEW GENERATION Arnab Roy Research Scholar National Institute of Technology, Durgapur Email: [email protected] Abstract: Indian English Literature refers to authors' body of work in India whose native or mother tongues might be one of India's several languages. It is also related to the work of Indian Diaspora members. It is also named Indo-Anglian literature. As a genre, this development is part of the larger spectrum of postcolonial literature. This paper discusses about Indian English novels after 1980. 1. Introduction This article attempts to consolidate Indian English Literature after 1980. There are a variety of books by literary artists such as SrinivasaIyengar, C.D. Narasimmaiya, M. K. Naik etc. that describe the beginning and development up to 1980. But the timely collection is not enough to date and this report is useful for a briefing on contemporary literary pedalling in around three-and-a-half decades. Apart from the deficiency of the correctly written root of the works consulted by Wikipedia, this kind of history is regularly obligatory. In India, post-colonial pressures played a critical and special position rather than post-war circumstances. It is true that an Indian genre called English writing has flourished unlimitedly and immensely and continues to thrive only during that time, i.e. after 1980. This paper is a study of Post- modern Indian English Novel, highlighting its history, themes adopted, andother aspects. 2. Historical past English isn't a foreign tongue to us. -

Download Download

ASIATIC, VOLUME 11, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2017 The Poetic Cosmos and Craftsmanship of a Bureaucrat Turned Poet: An Interview with Keki N. Daruwalla Goutam Karmakar1 National Institute of Technology Durgapur, India Keki Nasserwanji Daruwalla (1937-) occupies a distinctive position in the tradition of Indian English Poetry. The poet’s inimitable style, use of language and poetic ambience is fascinating. Daruwalla was born in pre-partition Lahore. His father Prof. N.C. Daruwalla moved to Junagadh, and later to Rampur and Ludhiana where the poet did his masters in English literature at Government College, Ludhiana (affiliated to Punjab University). In 1958, he joined the Indian Police Service and served the department remarkably well until 1974. An analyst of International relations in the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), he retired as Secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat and as Chairman JIC (Joint 1 Goutam Karmakar is currently pursuing his PhD in English at the National Institute of Technology Durgapur, India. He is a bilingual writer and his articles and research papers have been published in many International Journals. He has contributed papers in several edited books on Indian English literature. Email: [email protected]. Asiatic, Vol. 11, No. 1, June 2017 250 Goutam Karmakar Intelligence Committee). In 1970, he published his first volume of poetry Under Orion and has subsequently published several more: Apparition in April (1971), Crossing of Rivers (1976), Winter Poems (1980), The Keeper of the Dead (1982), Landscapes (1987), A Summer of Tigers (1995), Night River (2000), Map Maker (2002), The Scarecrow and the Ghost (2004), Collected Poems 1970-2005 (2006), The Glass blower – Selected Poems (2008) and Fire Altar: Poems on the Persians and the Greeks (2013). -

Singularities Vol-4-Issue-2

a peer reviewed international transdisciplinary biannual research journal Vol. 4 Issue 2 July 2017 Postgraduate Department of English Manjeri, Malappuram, Kerala. www.kahmunityenglish.in/journals/singularities Chief Editor P. K. Babu., Ph. D Principal, DGMMES Mampad College Members: Dr. K. K. Kunhammad Asst. Professor, Dept. of Studies in English, Kannur University Mammad. N Asst. Professor, Dept of English, Govt. College, Malappuram. Dr. Priya. K. Nair Asst. Professor, Dept. of English, St. Teresa's College, Eranakulam. Aswathi. M. P. Asst. Professor, Dept of English, KAHM Unity Women's College, Manjeri. Shahina Mol. A. K. Assistant Professor and Head Department of English, KAHM Unity Women’s College, Manjeri Advisory Editors: Dr. V. C. Haris School of Letters, M.G. University Kottayam Dr. M. V. Narayanan Assoc. Professor, Dept of English, University of Calicut. Editor's Note True research writing needs to take on the job of intellectually activating untrodden tangents. Singularities aspires to be a journal which not just records the researches through publishing, but one which also initiates dialogues and urges involvement. The Singularities conferences, envisaged as annual events, are meant to be exercises in pursuing the contemporary and wherever possible, to be efforts in leading the contemporary too. Space that permeates our existence, that influences the very way in which one experience, understand, navigate and recreate the world was selected as the theme for the annual conference of Singularities in 2017. The existence of space is irrevocably intertwined with culture, communication, technology, geography, history, politics, economics, and the lived experience. Understanding the spatial relationships, the tensions and dynamics that inform them, enables us to form insights into the process that configure the spaces we move through, inherit and inhabit. -

Research Paper Literature Margins of Mumbai: a Study on Representation of Margin in Jeet Thayil’S Narcopolis

Volume-3, Issue-11, Nov-2014 • ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Research Paper Literature Margins of Mumbai: a Study on Representation of Margin in Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis Veena S M.A English and Comparative Literature ABSTRACT The study tries to analyze the representation of minority in Jeet Thayil’s Narcopolis against the tradition of Bombay novels. It performs a thematic study on the novel and also the representation of the androgynous protagonist. KEYWORDS : Bombay Novels, Minority, Eunuch, Androgynous protagonist, Opium, Opium dens and Addiction “Bombay was central, had been so from the moment of its creation: castrated resulting in her erasure of distinct sexual identity and con- the bastard child of a Portuguese English wedding, and yet the most sequently addiction to opium. She works for her husband Rashid who Indian of Indian cities . all rivers flowed into its human sea. It was is also the den owner. an ocean of stories; we were all its narrators and everybody talked at once.” (Rushdie 350) Other people whose lives centers around opium include Salim, a co- caine peddler who is brutally sodomized by his master; Newton Xavi- Starting from the Midnight’s Children and The Moor’s Last Sigh, er, a famous artist and junkie drunk and Mr. Lee a Chinese drug deal- the city has become the setting of several novels in English owing er who initiates Dimple towards opium. It also deal with two kind of to its cultural, social and ethnic diversities that form a conglomerate. people put together in the same society – the one with choices and It was followed by a number of novels of Rohinton Mistry (Such A the one without them (Ahrestani 2) While Dimple, Salim and Mr. -

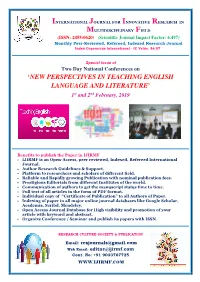

'New Perspectives in Teaching English Language And

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD (ISSN: 2455-0620) (Scientific Journal Impact Factor: 6.497) Monthly Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Research Journal Index Copernicus International - IC Value: 86.87 Special Issue of Two Day National Conferences on ‘NEW PERSPECTIVES IN TEACHING ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE’ 1st and 2nd February, 2019 Benefits to publish the Paper in IJIRMF IJIRMF is an Open-Access, peer reviewed, Indexed, Refereed International Journal. Author Research Guidelines & Support. Platform to researchers and scholars of different field. Reliable and Rapidly growing Publication with nominal publication fees. Prestigious Editorials from different Institutes of the world. Communication of authors to get the manuscript status time to time. Full text of all articles in the form of PDF format. Individual copy of “Certificate of Publication” to all Authors of Paper. Indexing of paper in all major online journal databases like Google Scholar, Academia, Scribd, Mendeley, Open Access Journal Database for High visibility and promotion of your article with keyword and abstract. Organize Conference / Seminar and publish its papers with ISSN. RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY & PUBLICATION Email: [email protected] Web Email: [email protected] Cont. No: +91 9033767725 WWW.IJIRMF.COM TWO DAY NATIONAL CONFERENCE on NEW PERSPECTIVES IN TEACHING ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 1st and 2nd February, 2019 The Managing Editor: Dr. Chirag M. Patel ( Research Culture Society & Publication – IJIRMF ) Co-editors: Dr. S.Niraimathi, M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D., M.Sc., ( Principal and Head, Department of English, Sri Sarada College for Women, Salem ) Dr. J.Thenmozhi, M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D., (Associate Professor of English, Sri Sarada College for Women, Salem) Dr. -

A Review of Indian English Literature

Volume II, Issue III, July 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 A REVIEW OF INDIAN ENGLISH LITERATURE Nasib Kumari Student J.k. Memorial College of Education Barsana Mor Birhi Kalan Charkhi Dadri Abstract Indian English literature (IEL) refers to the body of work by writers in India who write in the English language and wIhose native or co-native language could be one of the numerous languages of India. It is also associated with the works of members of the Indian diaspora, such as V. S. Naipaul, Kiran Desai, Jhumpa Lahiri, Agha Shahid Ali, Rohinton Mistry and Salman Rushdie, who are of Indian descent. It is frequently referred to as Indo-Anglian literature. (Indo-Anglian is a specific term in the sole context of writing that should not be confused with the term Anglo-Indian). As a category, this production comes under the broader realm of postcolonial literature- the production from previously colonised countries such as India. 1. HISTORY IEL has a relatively recent history; it is only one and a half centuries old. The first book written by an Indian in English was by Sake Dean Mahomet, titled Travels of Dean Mahomet; Mahomet''s travel narrative was published in 1793 in England. In its early stages it was influenced by the Western art form of the novel. Early Indian writers used English unadulterated by Indian words to convey an experience which was essentially Indian. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (1838–1894) wrote "Rajmohan''s Wife" and published it in the year 1864 which was the first Indian novel written in English. Raja (1908–2006), Indian philosopher and writer http://www.ijellh.com 354 Volume II, Issue III, July 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 authored Kanthapura and The Serpent and the Rope which are Indian in terms of its storytelling qualities. -

JEET THAYIL Is an Indian Poet, Novelist, Librettist and Musician. He

JEET THAYIL is an Indian poet, novelist, librettist and musician. He is best known as a poet and is the author of four collections: These Errors Are Correct (Tranquebar, 2008), English (2004, Penguin India, Rattapallax Press, New York, 2004),Apocalypso (Ark, 1997) and Gemini (Viking Penguin, 1992). His first novel, Narcopolis, (Faber & Faber, 2012), which won the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, was also shortlisted for the 2012 Man Booker Prize and the Hindu Literary Prize. His first novel, Narcopolis (Faber, 2011) is set mostly in Bombay in the 70s and 80s, and sets out to tell the city's secret history, when opium gave way to new cheap heroin. Thayil has said he wrote the novel, “to create a kind of memorial, to inscribe certain names in stone. As one of the characters [in Narcopolis] says, it is only by repeating the names of the dead that we honour them. I wanted to honour the people I knew in the opium dens, the marginalised, the addicted and deranged, people who are routinely called the lowest of the low; and I wanted to make some record of a world that no longer exists, except within the pages of a book.” He is the editor of the Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poets (Bloodaxe, U.K., 2008), 60 Indian Poets (Penguin India, 2008) and a collection of essays, Divided Time: India and the End of Diaspora (Routledge, 2006). He is the author of the libretto for the opera Babur in London, commissioned by the UK- based Opera Group with music by the Zurich-based British composer Edward Rushton. -

A History of Indian Poetry in English Edited by Rosinka Chaudhuri Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-07894-9 — A History of Indian Poetry in English Edited by Rosinka Chaudhuri Frontmatter More Information A HISTORY OF INDIAN POETRY IN ENGLISH A History of Indian Poetry in English explores the substance and genealogy of Anglophone verse in India from its nineteenth-century origins to the present day. Beginning with an extensive introduction that highlights the character and achievements of the field, this History includes essays that describe, analyze, and reflect on the legacy of Indian poetry written in English. Organized thematically, they survey the poetry of such diverse poets as Henry Derozio, Toru Dutt, Rabindranath Tagore, Nissim Ezekiel, Arun Kolatkar, A. K. Ramanujan, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Jayanta Mahapatra, Kamala Das, Melanie Silgardo, and Jeet Thayil. Written by scholars, critics, and poets, this History devotes special attention to the nineteenth- century forbears of the astonishing efflorescence of Indian poets in English in the twentieth century, while also exploring the role of diaspora and publishing in the constitution of some of this verse. This book is of pivotal importance to the understanding and analysis of Indian poetry in English and will serve as an invaluable reference for specialists and students alike. rosinka chaudhuri is Professor of Cultural Studies at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. Her books include Gentlemen Poets in Colonial Bengal: Emergent Nationalism and the Orientalist Project, Freedom and Beef Steaks: Colonial Calcutta Culture, and The Literary