Rebalancing the British Constitution the Future for Human Rights Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan's Parliament in the Making

Andrea Fleschenberg Afghanistan’s parliament in the making Gendered understandings and practices of politics in a transitional country Afghanistan’s parliament in the making 6cYgZV;aZhX]ZcWZg\!E]9!XjggZcianldg`hVhgZhZVgX]VhhdX^ViZVcYaZXijgZg Vii]Z>chi^ijiZd[HdX^VaHX^ZcXZVii]ZJc^kZgh^ind[=^aYZh]Z^b!<ZgbVcn# EgZk^djhan!h]ZlVhVgZhZVgX][ZaadlVii]Z>chi^ijiZd[:Vhi6h^VcHijY^Zh$Ed" a^i^XVaHX^ZcXZVii]ZJc^kZgh^ind[9j^hWjg\":hhZcVcYVaZXijgZgVii]ZJc^kZg" h^ind[8dad\cZ!<ZgbVcn#>c'%%,h]ZlVhVk^h^i^c\egd[ZhhdgVii]ZJc^kZgh^in d[i]ZEjc_VW^cAV]dgZ!EV`^hiVc!VcY^c'%%+Vii]ZJc^kZgh^iVi?VjbZ>^c 8VhiZaadc!HeV^c#=ZggZhZVgX]VgZVhVgZXdbeVgVi^kZVcYi]^gYldgaYeda^i^Xh l^i]VeVgi^XjaVg[dXjhdcHdji]VcYHdji]ZVhi6h^V!YZbdXgVi^oVi^dcVcY ZaZXi^dchijY^Zh!igVch^i^dcVa_jhi^XZ^hhjZh!\ZcYZgVcYeda^i^Xh!dcl]^X]h]Z ]VhXdcig^WjiZYcjbZgdjhejWa^XVi^dch# I]^hejWa^XVi^dclVhegZeVgZYl^i]hjeedgi[gdbi]ZJc^iZYCVi^dch9ZkZade" bZci;jcY[dgLdbZcJC>;:B"6[\]Vc^hiVc#I]Zk^ZlhVcYVcVanh^hXdc" iV^cZY^ci]ZejWa^XVi^dcVgZi]dhZd[i]ZVji]dgVcYYdcdicZXZhhVg^angZegZ" hZcii]Zk^Zlhd[JC>;:B!i]ZJc^iZYCVi^dchdgVcnd[^ihV[Äa^ViZYdg\Vc^oV" i^dch# 7^Wa^d\gVe]^XYViVd[i]Z<ZgbVcA^WgVgn I]Z<ZgbVcCVi^dcVaA^WgVgn9C7a^hihi]^hejWa^XVi^dc^ci]Z<ZgbVcCV" i^dcVa7^Wa^d\gVe]n#;dgYZiV^aZYW^Wa^d\gVe]^XYViVdca^cZ\did/]iie/$$YcW# YYW#YZ 6[\]Vc^hiVc¼heVga^VbZci^ci]ZbV`^c\ <ZcYZgZYjcYZghiVcY^c\hVcYegVXi^XZhd[eda^i^Xh^cVigVch^i^dcVaXdjcign 7n6cYgZV;aZhX]ZcWZg\ :Y^iZYWni]Z=Z^cg^X]7aa;djcYVi^dc >cXddeZgVi^dcl^i]JC>;:B =Z^cg^X]"7aa"Hi^[ijc\!7Zga^c'%%.0JC>;:B 6aag^\]ihgZhZgkZY :Y^i^c\/GdWZgi;jgadc\ E]didh/<jaWjYY^c:a]Vb 9Zh^\cVcYIneZhZii^c\/\gVe]^XhncY^XVi!B^X]VZaE^X`VgYi!7Zga^c -

Accountability for National Defence

Ideas IRPP Analysis Debate Study Since 1972 No. 4, March 2010 www.irpp.org Accountability for National Defence Ministerial Responsibility, Military Command and Parliamentary Oversight Philippe Lagassé While the existing regime to provide accountability for national defence works reasonably well, modest reforms that reinforce the convention of ministerial responsibility can improve parliamentary oversight and civilian control of the military. Le processus actuel de reddition de comptes en matière de défense nationale remplit son rôle ; toutefois, des réformes mineures renforçant la responsabilité ministérielle permettraient de consolider la surveillance parlementaire et la direction civile des forces militaires. Contents Summary 1 Résumé 2 Parliament and National Defence 5 The Government and National Defence 28 Notes and References 58 About This Study 61 The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRPP or its Board of Directors. IRPP Study is a refereed monographic series that is published irregularly throughout the year. Each study is subject to rigorous internal and external peer review for academic soundness and policy relevance. IRPP Study replaces IRPP Choices and IRPP Policy Matters. All IRPP publications are available for download at irpp.org. If you have questions about our publications, please contact [email protected]. If you would like to subscribe to our newsletter, Thinking Ahead, please go to our Web site, at irpp.org. ISSN 1920-9436 (Online) ISSN 1920-9428 (Print) ISBN 978-0-88645-219-3 (Online) ISBN 978-0-88645-221-6 (Print) Summary Canadians’ renewed focus on military matters reflects a desire to strengthen accountability for matters of national defence. -

Afghanistan's Parliament in the Making

The involvement of women in Afghanistan’s public life is decreasing. Attacks, vigilantism, and legal processes that contradict the basic principles of human and women’s rights are the order of the day. The security situation is worsening in step with the disenchantment E MAKING H arising from the lack of results and functional shortcomings of existing democratic structures. In the face of such difficulties, we often forget who should create the legal underpinnings for the power in Afghanistan: the women and men in parliament who are working to build a state in these turbulent times of transition. To what extent will these elected representatives succeed in creating alternatives to established traditional power structures? What are the obstacles they face? What kinds of networks or caucuses are they establishing? This book, which is based on interviews of male and female members of parliament held in Kabul in 2007 and 2008, examines the reali- IN T pARLIAMENT ANISTan’s H ties of parliamentary work in Afghanistan. It shows how varied and G coercive the patterns of identification prevalent in Afghanistan can AF be, and it provides a rare opportunity to gain insights into the self- images and roles of women in parliament. ISBN 978-3-86928-006-6 Andrea Fleschenberg Afghanistan’s parliament in the making Andrea Fleschenberg Gendered understandings and practices of politics in a transitional country .) ED BÖLL FOUNDATION ( BÖLL FOUNDATION H The Green Political Foundation Schumannstraße 8 10117 Berlin www.boell.de HEINRIC Afghanistan’s parliament in the making Andrea Fleschenberg, PhD, currently works as research associate and lecturer at the Institute of Social Science at the University of Hildesheim, Germany. -

Theparliamentarian

TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2015 | Issue Three XCVI | Price £13 Elections and Voting Reform PLUS Commonwealth Combatting Looking ahead to Millenium Development Electoral Networks by Terrorism in Nigeria CHOGM 2015 in Malta Goals Update: The fight the Commonwealth against TB Secretary-General PAGE 150 PAGE 200 PAGE 204 PAGE 206 The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) Shop CPA business card holders CPA ties CPA souvenirs are available for sale to Members and officials of CPA cufflinks Commonwealth Parliaments and Legislatures by CPA silver-plated contacting the photoframe CPA Secretariat by email: [email protected] or by post: CPA Secretariat, Suite 700, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA, United Kingdom. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. Calendar of Forthcoming Events Confirmed at 24 August 2015 2015 September 2-5 September CPA and State University of New York (SUNY) Workshop for Constituency Development Funds – London, UK 9-12 September Asia Regional Association of Public Accounts Committees (ARAPAC) Annual Meeting - Kathmandu, Nepal 14-16 September Annual Forum of the CTO/ICTs and The Parliamentarian - Nairobi, Kenya 28 Sept to 3 October West Africa Association of Public Accounts Committees (WAAPAC) Annual Meeting and Community of Clerks Training - Lomé, Togo 30 Sept to 5 October CPA International -

50 YEARS of EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY and Subjugated

European Parliament – 50th birthday QA-70-07-089-EN-C series 1958–2008 Th ere is hardly a political system in the modern world that does not have a parliamentary assembly in its institutional ‘toolkit’. Even autocratic or totalitarian BUILDING PARLIAMENT: systems have found a way of creating the illusion of popular expression, albeit tamed 50 YEARS OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY and subjugated. Th e parliamentary institution is not in itself a suffi cient condition for granting a democratic licence. Yet the existence of a parliament is a necessary condition of what 1958–2008 we have defi ned since the English, American and French Revolutions as ‘democracy’. Since the start of European integration, the history of the European Parliament has fallen between these two extremes. Europe was not initially created with democracy in mind. Yet Europe today is realistic only if it espouses the canons of democracy. In other words, political realism in our era means building a new utopia, that of a supranational or post-national democracy, while for two centuries the DNA of democracy has been its realisation within the nation-state. Yves Mény President of the European University Institute, Florence BUILDING PARLIAMENT: BUILDING 50 YEARS OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY PARLIAMENT EUROPEAN OF YEARS 50 ISBN 978-92-823-2368-7 European Parliament – 50th birthday series Price in Luxembourg (excluding VAT): EUR 25 BUILDING PARLIAMENT: 50 YEARS OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT HISTORY 1958–2008 This work was produced by the European University Institute, Florence, under the direction of Yves Mény, for the European Parliament. Contributors: Introduction, Jean-Marie Palayret; Part One, Luciano Bardi, Nabli Beligh, Cristina Sio Lopez and Olivier Costa (coordinator); Part Two, Pierre Roca, Ann Rasmussen and Paolo Ponzano (coordinator); Part Three, Florence Benoît-Rohmer; Conclusions, Yves Mény. -

House of Commons Commission

House of Commons Commission Thirty-sevene tht reporrt ofo the Commmim sssioion,, and annual repe ort ofo thee Admd inisi trrattioon Estimate Auddit Comommiitteee Financial Year 2014//151 House of Commons Commission Thirty-seventh report of the Commission, and annual report of the Administration Estimate Audit Committee Financial Year 2014/15 Report presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 1(3) of the House of Commons (Administration) Act 1978 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 21 July 2015 HC 341 London: The Stationery Office £13.50 Contents Foreword by the Speaker 3 Introduction by the Clerk of the House 5 How the House is governed 8 Strategy for the House of Commons Service 17 Making the House of Commons more effective 18 Making the House Administration more efficient 22 Ensuring that Members, staff and the public are well-informed 29 Working at every level to earn respect for the House of Commons 34 Annexes 40 Administration Estimate Audit Committee annual report 2014/15 57 Financial years are shown thus: 2014/15 Parliamentary sessions are shown thus: 2014-15 The Commission Annual Report for 2014/15 follows the same structure as the Corporate Business Plan 2014/15 in terms of the Strategy for the House of Commons Service 2013-17. 6 37th Report of the House of Commons Commission 37th Report of the House of Commons Commission 3 Foreword by the Speaker The last year has been one of monumental These new arrangements represent just the change for Parliament – structurally, first chapter in a new way of thinking for the historically, and also in terms of its House. -

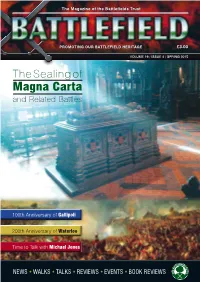

Battlefields 2015 Spring Issue

The Magazine of the Battlefields Trust PROMOTING OUR BATTLEFIELD HERITAGE £3.00 VOLUME 19 / ISSUE 4 / SPRING 2015 The Sealing of Magna Carta and Related Battles 100th Anniversary of Gallipoli 200th Anniversary of Waterloo Time to Talk with Michael Jones NEWS • WALKS • TALKS • REVIEWS • EVENTS • BOOK REVIEWS The Agincourt Archer On 25 October 1415 Henry V with a small English army of 6,000 men, made up mainly of archers, found himself trapped by a French army of 24,000. Although outnumbered 4 to 1 in the battle that followed the French were completely routed. It was one of the most remarkable victories in British history. The Battlefields Trust is commemorating the 600th anniversary of this famous battle by proudly offering a limited edition of numbered prints of well-known actor, longbow expert and Battlefields Trust President and Patron, Robert Hardy, portrayed as an English archer at the Battle of Agincourt. The prints are A4 sized and are being sold for £20.00, including Post & Packing. This is a unique opportunity; the prints are a strictly limited edition, so to avoid disappointment contact Howard Simmons either on email howard@ bhprassociates.co.uk or ring 07734 506214 (please leave a message if necessary) as soon as possible for further details. All proceeds go to support the Battlefields Trust. Battlefields Trust Protecting, interpreting and presenting battlefields as historical and educational The resources Agincourt Archer Spring 2015 Editorial Editors’ Letter Harvey Watson Welcome to the spring 2015 issue of Battlefield. At exactly 11.20 a.m. on Sunday 18 June 07818 853 385 1815 the artillery batteries of Napoleon’s army opened fire on the Duke Wellington’s combined army of British, Dutch and German troops who held a defensive position close Chris May to the village of Waterloo. -

The History of Parliament Trust REVIEW of ACTIVITIES 2015-16

The History of Parliament Trust REVIEW OF ACTIVITIES 2015-16 Annual review - 1 - Editorial Board Oct 2010 Objectives and activities of the History of Parliament Trust The History of Parliament is a major academic project to create a scholarly reference work describing the members, constituencies and activities of the Parliament of England and the United Kingdom. The volumes either published or in preparation cover the House of Commons from 1386 to 1868 and the House of Lords from 1603 to 1832. They are widely regarded as an unparalleled source for British political, social and local history. The volumes consist of detailed studies of elections and electoral politics in each constituency, and of closely researched accounts of the lives of everyone who was elected to Parliament in the period, together with surveys drawing out the themes and discoveries of the research and adding information on the operation of Parliament as an institution. The History has published 21,420 biographies and 2,831 constituency surveys in ten sets of volumes (41 volumes in all). They deal with 1386-1421, 1509-1558, 1558-1603, 1604-29, 1660- 1690, 1690-1715, 1715-1754, 1754-1790, 1790-1820 and 1820-32. All of these articles are now available on www.historyofparliamentonline.org . The History’s staff of professional historians is currently researching the House of Commons in the periods 1422-1504, 1640-1660, and 1832- 1868, and the House of Lords in the periods 1603-60 and 1660-1832. The three Commons projects currently in progress will contain a further 7,251 biographies of members of the House of Commons and 861 constituency surveys. -

October & November 2015 Newsletter

magnacarta800th.com Newsletter / Issue 19 October & November 2015 OCTOBER & NOVEMBER 2015 NEWSLETTER New Magna Carta Grant Available From FCO The Foreign Office The ‘Magna Carta At the event, FCO Minister Baroness Anelay said, ‘Democracy under the Rule has announced a new Partnerships’ Fund: of Law is the best form of governance £100,000 fund offering • Small grants from a £100,000 pilot we know - and the longer-term trend fund now available via a bidding is towards countries wanting more British legal expertise to process. democratic governance, not less. counties around the world The UK Government is committed to • Grants will be administered by supporting this. that want to improve the the FCO’s Human Rights and Rule of Law and their Democracy Department; click here Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond, for bidding and information. MP for Runnymede, was the principal democratic processes. Speaker at the 2015 800th “Kick -off” • Bids will be accepted until the dinner at the Guildhall on the 12th 31st December. January, 2015. Click here to watch his speech. Conference at Beijing’s Renmin University Law School, but Exhibition Cancelled The Hereford Magna Carta was to go on Sir Robert Worcester writes... exhibition at Renmin University, but Chinese Last spring I was surprised and delighted to receive an invitation asking me to participate in a meeting in Beijing’s authorities did not provide approval in time Renmin University of China Law School. There were a number and the exhibition was therefore shown at the of legal historians both from Renmin and other Chinese Law residence of the British Ambassador. -

D E P a Rtm E N T O F D Ista N C E Ed U C a Tio N Pu N Ja B I U N Ive Rsity

Department of Distance Education Punjabi University, Patiala (All Copyrights are Reserved) UNIT NO :- 2 M.A. (HISTORY) PART-I (SEMESTER-II) LESSON NO. : Note Note : 2.10 2.9 2.8 2.7 2.6 2.5 2.4 2.3 2.2 2.1 : department's website www.dccpbi.com Students can download the syllabus from the : : : : : : : : : England Act of 1832 Growth of Parliamentary System in Eastern Question (1832-1870) Eastern Question (1800-1832) The Unification of Germany, 1848-1871 The Unification of Germany, 1789-1848 The Unification of Italy, 1848-1870 The Unification of Italy, 1789-1848 Labour Movements in Europe Europe Rise and EnglandGrowth Act of 1867 ofGrowth Socialismof Parliamentaryin System in SECTION : B HISTORY HISTORY OF THE WORLD (1815-1870) PAPER-II M.A. (HISTORY) PART-I PAPER-II HISTORY OF THE WORLD (1815-1870) LESSON NO. 2.1 AUTHOR : DR. S.K. BAJAJ GROWTH OF PARLIAMENTARY SYSTEM IN ENGLAND- ACT OF 1832 Background The English Parliament is one of the unique representative institutions that appeared in Europe during the later Middle Ages. Its humble beginning can be traced to the Magna Carta of 1215, but it was in the reign of Edward I (1272-1307) that the expedient calling elected representatives of the countries and towns or brought to the King's Council or Parliament, was adopted The purpose of calling such representatives was to obtain their assent to the levying of taxes to meet the expenses of wars. In due course of time these representatives began to sit separately from the Peers ; this assembly thus, came to be known as the 'House of Commons'. -

March 2015 Newsletter

magnacarta800th.com Newsletter / Issue 13 March 2015 MARCH 2015 NEWSLETTER The four 1215 Magna Cartas were united for the first time in 800 years at theBritish Library between 2nd – 4th February, and at the House of Lords on 5th February 2015. On 20th February Temple Church hosted the fifth Magna Carta Stakeholder Networking Day. Organisations and groups committed to the anniversary updated each other on projects and key dates in the commemoration calendar. More on this below. The Magna Carta 800th Anniversary Commemoration Committee held a stand at the Global Law Summit between 23rd – 25th February with colleagues the Notaries Society. Visiting delegates expressed great interest in our commemoration events and objectives. March Highlights: April Highlights: • 1st: A ‘Read not Dead’ performance of ‘The • 1st: Lincoln Castle opens its new state-of-the-art Troublesome Reign of King John’ at Temple Church, Magna Carta vault (more on this below) from the Globe Theatre • 10th – 19th: The Globe Theatre’s run of • 5th: Seminar commemorating Magna Carta and the Shakespeare’s ‘King John’ at Temple Church Golden Bull hosted by the Embassy of Hungary • 12th – 16th: Commonwealth Lawyers’ Association • 7th: The English-Speaking Union Members’ Conference Glasgow Conference. Sir Robert Worcester speaking on • 16th: Professor Nigel Saul lecture, Hereford ‘My Magna Carta’ Cathedral: ‘Magna Carta and English History’ • 13th March – 1st September: British Library exhibition: • 22nd: Lord Janvrin lecture in Lincoln as part of the Law, Liberty, Legacy Lincoln Magna Carta Lecture Series • 14th – Finals of Historical Association’s Great • 24th: Magna Carta Constitutional Convention. Debate, Royal Holloway, University of London: ‘What Sponsored by Egham Museum, Eton and does Magna Carta mean to me?’ Wellington Colleges, the Supreme Court, Amnesty • 20th – Debate at Oxford Brookes: ‘On Liberties, International and Brunel University. -

Free Talks, Debates, Exhibitions and Walks

FREE TALKS, DEBATES, EXHIBITIONS AND WALKS Celebrating 800 years of rights and representation Houses of Parliament and venues across the UK 1 September – 25 October 2015 www.parliament.uk/festival-of-freedoms #freedomsfest BOOKING Most events are free of charge and booking in advance is required, unless otherwise stated. With noted exceptions, tickets can be booked via www.eventbrite.co.uk. See individual event listings within this booklet for full details. Admission is on a first-come-first-served basis. For ticketed events, as not everyone who books takes their place, to ensure a full house we offer more tickets than there are places. We cannot guarantee admission to latecomers, so please make sure you arrive promptly to avoid disappointment. Lunchtime events will last no more than 60 minutes and evening events will be approximately 75 minutes. Timings for walks and workshops vary and are detailed in individual listings within this booklet. For events taking place in the Houses of Parliament please allow at least 20 minutes to pass through security and at least 45 minutes during Open House Weekend (19 – 20 September). www.parliament.uk/visiting ACCESS INFORMATION You will find information that will help you to plan your visit, to all Festival of Freedom venues, on pages 21 – 22. Any questions? Email us at [email protected]. Telephone on 020 7219 4272 during our opening hours: 10am – 12pm and 2 – 4pm (Monday to Friday). Callers with a text phone can talk through Text Relay by calling 18001 followed by our full number 020 7219 4272. This brochure is available in a large print version.