Dismantling Discrimination in the Stairways and Halls of Nycha Using Local, State, and National Civil Rights Statutes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cohort 20 Graduation Celebration Ceremony February 7, 2020

COHORT 20 GRADUATION CELEBRATION CEREMONY FEBRUARY 7, 2020 Green City Force is an AmeriCorps program CONGRATULATIONS TO THE GRADUATES OF COHORT 20! WELCOME! Welcome to the graduation celebration for Green City Force’s (GCF) 20th Cohort! Green City Force’s AmeriCorps program prepares young adults, aged 18-24, who reside at NYCHA and have a high school diploma or equivalency for careers through green service. Being part of the Service Corps is a full-time commitment encompass- ing service, training, and skills-building experiences related to sustainable buildings and communities. GCF is committed to the ongoing success of our alumni, who num- ber nearly 550 with today’s graduates. The Corps Members of Cohort 20 represent a set of diverse experiences, hailing from 20 NYCHA developments and five boroughs. This cohort was the largest cohort as- signed to Farms at NYCHA, totaling 50 members for 8 and 6 months terms of service. The Cohort exemplifies our one corps sustainable cities service in response to climate resilience and community cohesion through environmental stewardship, building green infrastructure and urban farming, and resident education at NYCHA. We have a holistic approach to sustainability and pride ourselves in training our corps in a vari- ety of sectors, from composting techniques and energy efficiency to behavior change outreach. Cohort 20 are exemplary leaders of sustainability and have demonstrated they can confidently use the skills they learn to make real contributions to our City. Cohort 20’s service inspired hundreds of more residents this season to be active in their developments and have set a new standard for service that we are proud to have their successors learn from and exceed for even greater impact. -

First Annual Cops & Kids Awards and Recognition Ceremony in Staten

First-Class U. S . Postage Paid New York, NY Permit No. 4119 Vol. 40, No. 2 www.nyc.gov/nycha FEBRUARY 2010 First Annual Cops & Kids Awards and Recognition CeremonyBy Eileen Elliott in Staten Island WHEN POLICE OFFICERS SEE GROUPS OF TEENS ROAMING THE STREETS IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT, MORE OFTEN THAN NOT THEIR ASSUMPTION WILL BE THAT THE YOUTH ARE UP TO NO GOOD. So it was for Police Officer Dane Varriano and his partner of the 120th Precinct in Staten Island as they cruised past five teenagers strolling through Mariner’s Harbor Houses at two o’clock on Thanksgiving morning. As told by Depart- ment of Community Operations Senior Program Manager Raymond Diaz at the First Annual Cops and Kids Awards and Recognition Ceremony on January 7th, what could have been an unpleasant confronta- tion dissolved into friendly greetings when Officer Varriano recognized the young men. “Those are my guys. Everything’s cool,” the Officer explained to his partner. “These are the kids I play ball with.” The anecdote perfectly illus- dedicating yourself, and over long sweated with the kids during flag trates the goal of the NYPD periods of time that commitment football; and ultimately, what I Community Affairs’ Cops and Kids really does pay off.” started to see were relationships Program, which seeks to build Serving as Master of Cere- being built.” relationships between police offi- monies for the evening, Mr. Diaz One of those officers, NYPD cers and community youth thanked the many dedicated Community Affairs PAL Liaison through organized recreational people involved including Deputy Kerry Hylan described some hesi- activities — in this case, bowling, Inspector John Denesopolis from tancy on the part of the youth flag football and basketball. -

Annual Report 2020-2021

Application: Community Roots Charter School sandy lee - [email protected] 2020-2021 Annual Report Summary ID: 0000000120 Status: Annual Report Submission Last submitted: Jul 29 2021 06:53 PM (EDT) Entry 1 School Info and Cover Page Completed - Jul 26 2021 Instructions Required of ALL Charter Schools Each Annual Report begins with a completed School Information and Cover Page. The information is collected in a survey format within Annual Report portal. When entering information in the portal, some of the following items may not appear, depending on your authorizer and/or your responses to related items. Entry 1 School Information and Cover Page (New schools that were not open for instruction for the 2020-2021 school year are not required to complete or submit an annual report this year). Please be advised that you will need to complete this cover page (including signatures) before all of the other tasks assigned to you by your school's authorizer are visible on your task page. While completing this cover page task, please ensure that you select the correct authorizer (as of June 30, 2021) or you may not be assigned the correct tasks. BASIC INFORMATION 1 / 48 a. SCHOOL NAME (Select name from the drop down menu) COMMUNITY ROOTS CHARTER SCHOOL 331300860893 a1. Popular School Name (No response) b. CHARTER AUTHORIZER (As of June 30th, 2021) Please select the correct authorizer as of June 30, 2021 or you may not be assigned the correct tasks. NEW YORK CITY CHANCELLOR OF EDUCATION c. DISTRICT / CSD OF LOCATION CSD #13 - BROOKLYN d. DATE OF INITIAL CHARTER 12/2005 e. -

E-Mail Transmittal

Brooklyn Borough President Recommendation CITY PLANNING COMMISSION 120 Broadway, 31st Floor, New York, NY 10271 [email protected] INSTRUCTIONS 1. Return this completed form with any attachments to the Calendar Information Office, City Planning Commission, Room 2E at the above address. 2. Send one copy with any attachments to the applicant’s representatives as indicated on the Notice of Certification. APPLICATION 86 FLEET PLACE – N 210061 ZMK An application submitted by Red Apple 86 Fleet Place Development LLC, pursuant to Sections 197-c and 201 of the New York City Charter, for a text amendment to sections of the New York City Zoning Resolution (ZR) that limit what uses can be located within 50 feet of a property’s street line on designated streets in the Special Downtown Brooklyn District (SDBD). The requested actions would allow all non-residential use groups permitted by the underlying C6-4 zoning, including community facilities at 86 Fleet Place, an existing 32-story building located on the south side of Myrtle Avenue between Fleet Place and a de-mapped portion of Prince Street in Brooklyn Community District 2 (CD 2). BROOKLYN COMMUNITY DISTRICT NO. 2 BOROUGH OF BROOKLYN RECOMMENDATION APPROVE DISAPPROVE APPROVE WITH DISAPPROVE WITH MODIFICATIONS/CONDITIONS MODIFICATIONS/CONDITIONS SEE ATTACHED February 3, 2021 BROOKLYN BOROUGH PRESIDENT DATE RECOMMENDATION FOR: 86 FLEET PLACE – N 210061 ZMK Red Apple 86 Fleet Place Development LLC submitted an application pursuant to Sections 197-c and 201 of the New York City Charter, for a text amendment to sections of the New York City Zoning Resolution (ZR) that limit what uses can be located within 50 feet of a property’s street line on designated streets in the Special Downtown Brooklyn District (SDBD). -

Elevator Action Plan

Office of the NYCHA FEDERAL MONITOR Bart M. Schwartz Pursuant to Agreement dated January 31, 2019 415 Madison Avenue 11th Floor New York, New York 10017 212.817.6733 Transmittal To: Greg Russ, Chair and CEO, NYCHA, via email: [email protected] Rob Yalen, AUSA, SDNY, via email: [email protected] Daniel W. Sherrod, via email: [email protected] From: Bart M. Schwartz NYCHA Federal Monitor Date: January 30, 2020 Subject: Transmittal of Approved Elevator Action Plan Transmitted herewith, after consultation with each of your offices, attached you will find in final version, NYCHA Elevator Action Plan, pursuant to ¶ 8 and subject to ¶¶ 36 through 43 of the Agreement, which I as Monitor have approved. Please contact Daniel Brownell should you have any questions. Thanks to all of you for your efforts and help in completing this. Bart M. Schwartz New York City Housing Authority Action Plan – Elevators Obligations: Exhibit B. C.21, C.22, C.23, C.24, C. 25, C.26, C.27, C.28, C.29, C.30, C.31, C.32, C.33, C.34 January 31, 2020 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Elevator Criticality and Risk Map.................................................................................................... -

Park Slope Historic District Extension II Designation Report April 12, 2016

Park Slope Historic District Extension II Designation Report April 12, 2016 Cover Photograph: 60 Prospect Place, built 1887, C.P.H. Gilbert architect, Queen Anne style. Photo: Jessica Baldwin, 2016 Park Slope Historic District Extension II Designation Report Essay Written by Donald G. Presa Building Profiles Prepared by Donald G. Presa, Theresa Noonan, and Jessica Baldwin Architects’ Appendix Researched and Written by Donald G. Presa Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Donald G. Presa, Theresa Noonan, and Jessica Baldwin Map by Daniel Heinz Watts Commissioners Meenakshi Srinivasan, Chair Frederick Bland Michael Goldblum Diana Chapin John Gustafsson Wellington Chen Adi Shamir-Baron Michael Devonshire Kim Vauss Sarah Carroll, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Lisa Kersavage, Director of Special Projects and Strategic Planning Jared Knowles, Director of Preservation PARK SLOPE HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION II MAP ................................. after Contents TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................. 1 PARK SLOPE HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION II BOUNDARIES ...................................... 1 SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 5 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PARK SLOPE HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION II Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

![[Desire for Diversity and Difference in Gentrified Brooklyn] Dialogue Between a Planner and a Sociologist](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7606/desire-for-diversity-and-difference-in-gentrified-brooklyn-dialogue-between-a-planner-and-a-sociologist-2047606.webp)

[Desire for Diversity and Difference in Gentrified Brooklyn] Dialogue Between a Planner and a Sociologist

Sandra Annunziata, Lidia K.C. Manzo [Desire for Diversity and Difference in Gentrified Brooklyn] Dialogue between a planner and a sociologist Abstract:This paper combines two ethnographic experiences conducted in two Brooklyn neighborhoods, with the aim to understand the gentrification process: its plural and multidimensional character and the contextual variables. However, coming from different paradigms they are less interested in doing a comparison of their case studies than presenting how different perspectives see and problematize gentrification and urban change in the face of diversity. In this light, the paper discusses the authors’ first-hand experiences and results from the field research as in a sort of dialogue with the academic reader. Reflection on how do they see and problematize gentrification and diversity, the social effects of displacement and the role of planning conclude the paper. Keywords:Gentrification, Urban Desire, Diversity, Brooklyn, Park Slope, Fort Greene. Introduction This paper combines two ethnographic experiences independently conducted by the authors in two Brooklyn neighborhoods1. The overall goal of their work was to understand the process of gentrification: its plural and multidimensional character and the contextual variables of its process (Malutas 2011; Lees et al 2008). However, coming from different paradigms and carrying with them their backgrounds in planning and sociology, they are less interested in doing a comparison of their studies (already published as Annunziata 2009 and Manzo 2012) than presenting how different perspectives see and problematize gentrification and urban change. In this light, the paper discusses the authors’ first-hand experiences and results from the field research as in a sort of dialogue with the academic reader. -

Brooklyn Paper It Is Perhaps the Only Time and Place in New York City That People Don’T on Way Out, Doctoroff Mind Sitting in Traffic

SHOP LOCALLY! SEE HOLIDAY GIFT GUIDE IN P.9 Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2007 BROOKLYN HTS–CGARDENS–DTOWN–FT GREENE EDITIONS AWP/16 pages • Vol. 30, No. 49 • Saturday, Dec. 15, 2007 • FREE INCLUDING DUMBO, CLINTON HILL, COBBLE HILL, BOERUM HILL Dyker does it NOW HE again TELLS US! By Joe Jordan for The Brooklyn Paper It is perhaps the only time and place in New York City that people don’t On way out, Doctoroff mind sitting in traffic. It’s Christmas in Dyker Heights! The otherwise sleepy neighborhood is once again decking the halls and delight- ing residents and tourists alike with its admits AY process bad over-the-top, make-Disney-World-jealous / Joe Jordan Christmas displays. By Gersh Kuntzman Although local residents get to enjoy their neighbors’ extravaganzas annually The Brooklyn Paper — “We do this every year,” says Dyker Departing Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff took a parting shot at the Atlantic Yards mega-devel- resident Guisseppe Bonofrio — for others, Paper The Brooklyn See DYKER on page 13 The Spata home on 84th Street in Dyker Heights is one of the most popular in Brooklyn. opment this week, offering the stunning admis- sion that if the city had to do it all over again, it would have demanded a proper public review of the $4-billion project. In an interview with the New York Observer, Doctoroff suggested that he was wrong to sign off F C MORE INSIDE line gets a -minus Atlantic Yards’ 4th anniversary: P. 6 New Yards security concerns: P. -

Fort Greene and Clinton Hill

in Fort Greene & Clinton Hill, Brooklyn 2011 Community Food Assessment with 2012 updates in Fort Greene and Clinton Hill, and with guidance from various Get Fresh! Food access, food justice and collective action in Fort Greene & Clinton Hill 2011 Community Food Assessment with 2012 Updates Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................3 About MARP ..................................................................................................................................................5 2012 Updates ................................................................................................................................................6 The Fort Greene & Clinton Hill Community Food Council Steering Committee .......................................6 A Changing Local Food Environment .........................................................................................................7 Emergency Food Pantry Closures ..............................................................................................................8 Build Up and Upon Our Work ....................................................................................................................8 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................9 Introduction to Fort Greene and Clinton Hill ............................................................................................9 -

Whitman Publication PRINT 4.Indd

CELEBRATING 200 YEARS OF THE BARD OF DEMOCRACY ALL OF WHITMAN AT 200 MAY BROOKLYN PUBLIC LIBRARY JUNE GROLIER CLUB UNTIL UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA A year-long series of events A weekend of poetry, music, An all day public Whitman JULY An exhibition displaying fi rst 20 and commissions by University 18 and debate about Walt 01 symposium, in conjunction printings of Leaves of Grass, early of Pennsylvania Libraries and Whitman. Includes poets with the exhibition Poet drafts of his poems in manuscript, dozens of partner orgs across Vijay Seshadri, Tina Chang, of the Body: New York’s 27 personal correspondence, and 19 the Philadelphia region. and Martín Espada. Walt Whitman. photographs. PAGE 05 PAGE 03 PAGE 04 PAGE 06 2019 EVENTS INSIDE America Celebrates WALT WHITMAN A PUBLICATION AMPLIFYING WHITMAN 1819-2019 BICENTENNIAL CELEBRATIONS IN 2019 “I celebrate myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. ” —WALT WHITMAN, Song of Myself Karen Karbiener Walt Whitman Bicentennial CALENDAR OF EVENTS SINGING YOURSELVES, WALT WHITMAN Over 50 organizations are hosting exhibitions, poetry readings, music, and lectures across America celebrating the life of Walt Whitman. Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, Disorderly, fl eshy and sensual… eating drinking and breeding, 03 No sentimentalist…. no stander above men and women or apart from them…. no more modest than immodest. Unscrew the locks from the doors! Walt Whitman Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs! 1 SONG OF MYSELF alt Whitman introduces himself in the middle of sible or aloof, but looks and speaks and even dreams like Walt Whitman celebrates himself and, the fi rst poem of the fi rst edition of Leaves of Grass, us. -

1 SUPREME COURT of the STATE of NEW YORK COUNTY of NEW YORK in the Matter of the Application Of

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK In the Matter of the Application of: THE CITY-WIDE COUNCIL OF PRESIDENTS Index No. ___________________ and AT-RISK COMMUNITY SERVICES INC., Petitioners, Assigned to Justice ____________ For a Judgment Pursuant to Article 78 of the Civil Date Purchased: Practice Law and Rules, VERIFIED ARTICLE 78 -against- PETITION THE NEW YORK CITY HOUSING AUTHORITY and SHOLA OLATOYE, as Chair of the New York City Housing Authority, Respondents. “NYCHA has an obligation to protect the residents of its buildings. Its failure to do so . is inexcusable.” - Commissioner Mark Peters, NYC Dep’t of Investigation (3/28/17) Petitioners, the City-wide Council of Presidents (“CCOP”) and At-Risk Community Services Inc. (“At-Risk”), by and through their attorneys, Walden Macht & Haran LLP, for their verified petition, allege the following: INTRODUCTION 1. In many important and fundamental ways, the New York City Housing Authority (“NYCHA”) has exhibited a pattern and practice of failing to protect New York’s low-income community members (“Tenants”), including through blatant violations of the law. These failures include, but are in no way limited to, failure to protect Tenants from toxic lead, mold and other moisture problems, vermin, roaches, violent offenders who are actively engaging in criminal activity, broken entryway and apartment locks, and dangerous, 1 malfunctioning elevators. NYCHA is currently failing in its duty to provide heat during bitter winter temperatures, which affects hundreds of thousands of Tenants and has resulted in extreme physical hardship. 2. These problems have led to (a) numerous deaths, injuries, and sickness, (b) criminal and civil investigations and cases, (c) multiple findings of wrong-doing by the NYC Department of Investigation (“DOI”), including a November 14, 2017 Report regarding False Certification of NYCHA Lead Paint Inspections (the “DOI Report,” a true and correct copy of which is attached hereto as Ex. -

Existing Land Use / Description of Neighborhoods

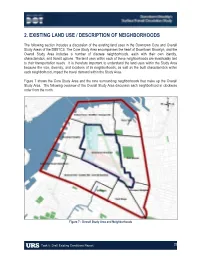

2. EXISTING LAND USE / DESCRIPTION OF NEIGHBORHOODS The following section includes a discussion of the existing land uses in the Downtown Core and Overall Study Areas of the DBSTCS. The Core Study Area encompasses the heart of Downtown Brooklyn, and the Overall Study Area includes a number of discrete neighborhoods, each with their own identity, characteristics, and transit options. The land uses within each of these neighborhoods are inextricably tied to their transportation needs. It is therefore important to understand the land uses within the Study Area because the size, diversity, and locations of its neighborhoods, as well as the built characteristics within each neighborhood, impact the travel demand within the Study Area. Figure 7 shows the Core Study Area and the nine surrounding neighborhoods that make up the Overall Study Area. The following overview of the Overall Study Area discusses each neighborhood in clockwise order from the north. Figure 7 - Overall Study Area and Neighborhoods Task 6: Draft Existing Conditions Report 23 2.1 OVERALL STUDY AREA Fulton Ferry / DUMBO / Vinegar Hill Fulton Ferry/DUMBO/Vinegar Hill is the area to the north of Downtown Brooklyn generally bounded by the East River to the north, Navy Street to the east, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) and High Street to the south, and the Brooklyn Bridge overpass to the west. Fulton Ferry (sometimes called Fulton Landing) lies where the foot of Old Fulton Street meets the waterfront. In the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, this neighborhood contains a range of land uses, including residential (in converted loft buildings) and commercial (restaurants and local retail) uses; there are also a few vacant lots and vacant former service stations.