Chapter13.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herein After Termed As Gulf) Occupying an Area of 7300 Km2 Is Biologically One of the Most Productive and Diversified Habitats Along the West Coast of India

6. SUMMARY Gulf of Katchchh (herein after termed as Gulf) occupying an area of 7300 Km2 is biologically one of the most productive and diversified habitats along the west coast of India. The southern shore has numerous Islands and inlets which harbour vast areas of mangroves and coral reefs with living corals. The northern shore with numerous shoals and creeks also sustains large stretches of mangroves. A variety of marine wealth existing in the Gulf includes algae, mangroves, corals, sponges, molluscs, prawns, fishes, reptiles, birds and mammals. Industrial and other developments along the Gulf have accelerated in recent years and many industries make use of the Gulf either directly or indirectly. Hence, it is necessary that the existing and proposed developments are planned in an ecofriendly manner to maintain the high productivity and biodiversity of the Gulf region. In this context, Department of Ocean Development, Government of India is planning a strategy for management of the Gulf adopting the framework of Integrated Coastal and Marine Area Management (ICMAM) which is the most appropriate way to achieve the balance between the environment and development. The work has been awarded to National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa. NIO engaged Vijayalakshmi R. Nair as a Consultant to compile and submit a report on the status of flora and fauna of the Gulf based on secondary data. The objective of this compilation is to (a) evolve baseline for marine flora and fauna of the Gulf based on secondary data (b) establish the prevailing biological characteristics for different segments of the Gulf at macrolevel and (c) assess the present biotic status of the Gulf. -

The Nordic Countries and the European Security and Defence Policy

bailes_hb.qxd 21/3/06 2:14 pm Page 1 Alyson J. K. Bailes (United Kingdom) is A special feature of Europe’s Nordic region the Director of SIPRI. She has served in the is that only one of its states has joined both British Diplomatic Service, most recently as the European Union and NATO. Nordic British Ambassador to Finland. She spent countries also share a certain distrust of several periods on detachment outside the B Recent and forthcoming SIPRI books from Oxford University Press A approaches to security that rely too much service, including two academic sabbaticals, A N on force or that may disrupt the logic and I a two-year period with the British Ministry of D SIPRI Yearbook 2005: L liberties of civil society. Impacting on this Defence, and assignments to the European E Armaments, Disarmament and International Security S environment, the EU’s decision in 1999 to S Union and the Western European Union. U THE NORDIC develop its own military capacities for crisis , She has published extensively in international N Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: H management—taken together with other journals on politico-military affairs, European D The Processes and Mechanisms of Control E integration and Central European affairs as E ongoing shifts in Western security agendas Edited by Wuyi Omitoogun and Eboe Hutchful R L and in USA–Europe relations—has created well as on Chinese foreign policy. Her most O I COUNTRIES AND U complex challenges for Nordic policy recent SIPRI publication is The European Europe and Iran: Perspectives on Non-proliferation L S Security Strategy: An Evolutionary History, Edited by Shannon N. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

Dictionary on Comprehensive Security in Indonesia: Acronym and Abbreviations

Dictionary on Comprehensive Security in Indonesia: Acronym and Abbreviations Kamus Keamanan Komprehensif Indonesia: Akronim dan Singkatan Dr. Ingo Wandelt Kamus Keamanan Komprehensif Indonesia : Akronim dan Singkatan 1 Dictionary on Comprehensive Security in Indonesia: Acronym and Abbreviations Kamus Keamanan Komprehensif Indonesia: Akronim dan Singkatan Dr. Ingo Wandelt November 2009 2 Dictionary on Comprehensive Security in Indonesia : Acronym and Abbreviations Kamus Keamanan Komprehensif Indonesia : Akronim dan Singkatan 1 Dictionary on Comprehensive Security in Indonesia: Kamus Keamanan Komprehensif Indonesia: Acronym and Abbreviations Akronim dan Singkatan By: Disusun Oleh: Dr. Ingo Wandelt Dr. Ingo Wandelt Published by: Diterbitkan oleh : Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) Indonesia Office Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) Indonesia Office Cover Design & Printing: Design & Percetakan: German-Indonesian Chamber of Industry and Commerce (EKONID) Perkumpulan Ekonomi Indonesia-Jerman (EKONID) All rights reserved. Hak cipta dilindungi Undang-undang. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Dilarang memperbanyak sebagian atau seluruh isi terbitan ini dalam bentuk apapun tanpa izin tertulis dari FES Indonesia. Tidak untuk diperjualbelikan. Second Edition Edisi Kedua Jakarta, November 2009 Jakarta, November 2009 ISBN: 978-979-19998-5-4 ISBN: 978-979-19998-5-4 2 Dictionary on Comprehensive Security in Indonesia : Acronym and Abbreviations Kamus Keamanan Komprehensif Indonesia : Akronim dan Singkatan 3 Content I Daftar Isi Foreword ........................................................................................... -

T He Indian Army Is Well Equipped with Modern

Annual Report 2007-08 Ministry of Defence Government of India CONTENTS 1 The Security Environment 1 2 Organisation and Functions of The Ministry of Defence 7 3 Indian Army 15 4 Indian Navy 27 5 Indian Air Force 37 6 Coast Guard 45 7 Defence Production 51 8 Defence Research and Development 75 9 Inter-Service Organisations 101 10 Recruitment and Training 115 11 Resettlement and Welfare of Ex-Servicemen 139 12 Cooperation Between the Armed Forces and Civil Authorities 153 13 National Cadet Corps 159 14 Defence Cooperaton with Foreign Countries 171 15 Ceremonial and Other Activities 181 16 Activities of Vigilance Units 193 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 199 Appendices I Matters Dealt with by the Departments of the Ministry of Defence 205 II Ministers, Chiefs of Staff and Secretaries who were in position from April 1, 2007 onwards 209 III Summary of latest Comptroller & Auditor General (C&AG) Report on the working of Ministry of Defence 210 1 THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Troops deployed along the Line of Control 1 s the world continues to shrink and get more and more A interdependent due to globalisation and advent of modern day technologies, peace and development remain the central agenda for India.i 1.1 India’s security environment the deteriorating situation in Pakistan and continued to be infl uenced by developments the continued unrest in Afghanistan and in our immediate neighbourhood where Sri Lanka. Stability and peace in West Asia rising instability remains a matter of deep and the Gulf, which host several million concern. Global attention is shifting to the sub-continent for a variety of reasons, people of Indian origin and which is the ranging from fast track economic growth, primary source of India’s energy supplies, growing population and markets, the is of continuing importance to India. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., MARCH 5, 2019 1 ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, MARCH 5, 2019 PART II Statutory Notifications, (S.R.O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (Navy Branch) NOTIFICATIONS Rawalpindi, the 25th February, 2019 S.R.O. 283(I)/2019.—The following confirmation is made in the rank of Lieut under N.I. 20/71: Pakistan Navy Ag Lt to be Lt Date of Seniority Date of Grant of Gained during S. No Rank/Name/P No Confirmation SSC as Ag Training as Lt Lt (M-D) Ag Lt (SSC)(WE) 06-01-14 with 1. Muhammad Fawad Hussain PN 06-01-14 +01-25 seniority from (P No 9094) 11-11-13 [Case No.CW/0206/70/PC/NHQ/ dated.] (1) Price: Rs. 20.00 [340(2019)/Ex. Gaz.] 2 THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., MARCH 5, 2019 [PART II S.R.O. 284(I)/2019.—Following officers are granted local rank of Commander w.e.f the dates mentioned against their names under NR-0634: S. No. Rank/Name/P No Date of Grant of Local Rank of Cdr OPERATIONS BRANCH 1. Lt Cdr (Ops) Muhammad Saleem PN 06-05-18 (P No 5111) 2. Lt Cdr (Ops) Wasim Zafar PN 01-07-18 (P No 6110) 3. Lt Cdr (Ops) Mubashir Nazir Farooq PN 01-07-18 (P No 6204) 4. Lt Cdr (Ops) Mohammad Ayaz PN 01-07-18 (P No 6217) 5. Lt Cdr (Ops) Tahir Majeed Asim TI(M) PN 01-07-18 (P No 6229) 6. Lt Cdr (Ops) Muhammad Farman PN 01-07-18 (P No 6209) 7. -

Revised Tri Ser Pen Code 11 12 for Printing

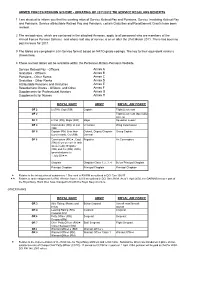

ARMED FORCES PENSION SCHEME - UPRATING OF 2011/2012 TRI SERVICE REGULARS BENEFITS 1 I am directed to inform you that the existing rates of Service Retired Pay and Pensions, Service Invaliding Retired Pay and Pensions, Service attributable Retired Pay and Pensions, certain Gratuities and Resettlement Grants have been revised. 2 The revised rates, which are contained in the attached Annexes, apply to all personnel who are members of the Armed Forces Pension Scheme and whose last day of service is on or after the 31st March 2011. There has been no pay increase for 2011. 3 The tables are compiled in a tri-Service format based on NATO grade codings. The key to their equivalent ranks is shown here. 4 These revised tables will be available within the Personnel-Miltary-Pensions Website. Service Retired Pay - Officers Annex A Gratuities - Officers Annex B Pensions - Other Ranks Annex C Gratuities - Other Ranks Annex D Attributable Pensions and Gratuities Annex E Resettlement Grants - Officers, and Other Annex F Supplements for Professional Aviators Annex G Supplements for Nurses Annex H ROYAL NAVY ARMY ROYAL AIR FORCE OF 2 Lt (RN), Capt (RM) Captain Flight Lieutenant OF 2 Flight Lieutenant (Specialist Aircrew) OF 3 Lt Cdr (RN), Major (RM) Major Squadron Leader OF 4 Commander (RN), Lt Col Lt Colonel Wing Commander (RM), OF 5 Captain (RN) (less than Colonel, Deputy Chaplain Group Captain 6 yrs in rank), Col (RM) General OF 6 Commodore (RN)«, Capt Brigadier Air Commodore (RN) (6 yrs or more in rank (preserved)); Brigadier (RM) and Col (RM) (OF6) (promoted prior to 1 July 00)«« Chaplain Chaplain Class 1, 2, 3, 4 Below Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain « Relates to the introduction of substantive 1 Star rank in RN/RM as outlined in DCI Gen 136/97 «« Relates to rank realignment for RM, effective from 1 Jul 00 as outlined in DCI Gen 39/99. -

The Other Battlefield Construction And

THE OTHER BATTLEFIELD – CONSTRUCTION AND REPRESENTATION OF THE PAKISTANI MILITARY ‘SELF’ IN THE FIELD OF MILITARY AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE PRODUCTION Inauguraldissertation an der Philosophisch-historischen Fakultät der Universität Bern zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde vorgelegt von Manuel Uebersax Promotionsdatum: 20.10.2017 eingereicht bei Prof. Dr. Reinhard Schulze, Institut für Islamwissenschaft der Universität Bern und Prof. Dr. Jamal Malik, Institut für Islamwissenschaft der Universität Erfurt Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Webserver der Universitätsbibliothek Bern Dieses Werk ist unter einem Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung 2.5 Schweiz Lizenzvertrag lizenziert. Um die Lizenz anzusehen, gehen Sie bitte zu http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ oder schicken Sie einen Brief an Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA. 1 Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Dokument steht unter einer Lizenz der Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung 2.5 Schweiz. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ Sie dürfen: dieses Werk vervielfältigen, verbreiten und öffentlich zugänglich machen Zu den folgenden Bedingungen: Namensnennung. Sie müssen den Namen des Autors/Rechteinhabers in der von ihm festgelegten Weise nennen (wodurch aber nicht der Eindruck entstehen darf, Sie oder die Nutzung des Werkes durch Sie würden entlohnt). Keine kommerzielle Nutzung. Dieses Werk darf nicht für kommerzielle Zwecke verwendet werden. Keine Bearbeitung. Dieses Werk darf nicht bearbeitet oder in anderer Weise verändert werden. Im Falle einer Verbreitung müssen Sie anderen die Lizenzbedingungen, unter welche dieses Werk fällt, mitteilen. Jede der vorgenannten Bedingungen kann aufgehoben werden, sofern Sie die Einwilligung des Rechteinhabers dazu erhalten. Diese Lizenz lässt die Urheberpersönlichkeitsrechte nach Schweizer Recht unberührt. -

98Th WORLD HYDROGRAPHY DAY CELEBRATION in INDONESIA

1 HYDROGRAPHIC AND OCEANOGRAPHIC CENTER, THE INDONESIAN NAVY Pantai Kuta V No.1 Jakarta 14430 Indonesia Phone. (+62)21.6470.4810 Fax. (+62)21.6471.4819 E-mail: [email protected] 98th WORLD HYDROGRAPHY DAY CELEBRATION IN INDONESIA IHO and its currently 89 Member States will reaffirm their commitment to raising awareness of the importance of hydrography and continue to coordinate their activities, in particular through maintaining and publishing relevant international standards, providing capacity building and assistance to those countries. Hydrographic services require improvement and by encouraging the collection and discovery of new hydrographic data through new emerging technologies and by ensuring the widest possible availability of this data through the development of national and regional Marine Spatial Data Infrastructures. As a national hydrographic office and member of the IHO, Pushidrosal has a cooperation with other agencies such as government agencies, maritime industries, scientists, colleges and hydrographic communities. To commemorate the 98th World Hydrography Day 2019 themed Hydrographic Information Driving Marine Knowledge, Pushidrosal held a number of activities such as Hydrographic Seminar, MSS ENC Workshop and FGD Marine Cartography. The Hydrographic Seminar was held to obtained an information and advice from other agencies and experts in order to formulating policies on navigation savety and marine development. The provision of human resources is one of a concern. 2 Indonesia (as MSS ENC coordinator and administrator), has organized the MSS ENC Workshop. The patterns and procedures to managing MSS ENC are dicussed. Either Navigation safety in the Malacca Strait and Singapore strait. The Marine Cartography Focus Discussion Group (FGD) was held to look for answer regarding the fulfillment of human resource who have Marine Cartography capabilities. -

A Preliminary Assessment of Indonesia's Maritime Security

A Preliminary Assessment of Indonesia’s Maritime Security Threats and Capabilities Lyle J. Morris and Giacomo Persi Paoli CORPORATION For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2469 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. RAND Europe is a not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Preface Indonesia is the largest archipelago in the world and is situated at one of the most important maritime crossroads in the Indo-Pacific region. Located between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, Indonesia provides a central conduit for global shipping via the Strait of Malacca – a major shipping channel through which 30 per cent of global maritime trade passes. It is also home to several other key maritime transit points, such as the Makassar, Sunda and Lombok Straits. -

Indo-Pakistan War

WAR OF 1971 INDO-PAKISTAN WAR Sonam Pawar Purushottum Walawalkar higher secondary school 1 Goa naval unit • The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971was a military confrontation between India‘s forces and Pakistan that occurred during the Bangladesh Liberation War in East Pakistan from 3 December 1971 to 16 December 1971. The war began with Operation Chengiz Khan's preemptive aerial strikes on 11 Indian air stations, which led to the commencement of hostilities with Pakistan and Indian entry into the war for independence in East Pakistan on the side of Bengali nationalist forces. Lasting just 13 days, it is one of the shortest warsin history. In the process, it also become part of the nine-month long Bangladesh Liberation War. • During the war, Indian and Pakistani militaries simultaneously clashed on the eastern and western fronts. The war ended after the Eastern Command of the Pakistan mIlitary signed the Instrument of Surrenderon 16December 1971in Dhaka, marking the formation of East Pakistan as the new nation of Bangladesh. Officially, East Pakistan had earlier called for its secession from Pakistan on 26 March 1971. Approximately 90,000to 93,000 Pakistani servicemen were taken prisoner by the Indian Army, which included 79,676 to 81,000 uniformed personnel of the Pakistan Armed Forces, including some Bengali soldiers who had remained loyal to Pakistan. The remaining 10,324 to 12,500 prisoners were civilians, either family members of the military personnel or collaborators. • It is estimated that members of the Pakistani military and supporting pro Pakistani Islamist militias killed between 300,000 and 3,000,000 civilians in Bangladesh.