Porch Light Program: Final Evaluation Report Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cass-Capco Institute Paper Series on Risk

the journal of financial transformation journal 03/2009/#25 Cass-Capco Institute Paper Series on Risk Recipient of the APEX Awards for Publication Excellence 2002-2008 Minimise risk, optimise success With a Masters degree from Cass Business School, you will gain the knowledge and skills to stand out in the real world. MSc in Insurance and Risk Management Cass is one of the world’s leading academic centres For applicants to the Insurance and Risk in the insurance field. What's more, graduates Management MSc who already hold a from the MSc in Insurance and Risk Management CII Advanced Diploma, there is a fast-track gain exemption from approximately 70% of the January start, giving exemption from the examinations required to achieve the Advanced first term of the degree. Diploma of the Chartered Insurance Institute (ACII). To find out more about our regular information sessions, the next is 10 April 2008, visit www.cass.city.ac.uk/masters and click on 'sessions at Cass' or 'International & UK'. Alternatively call admissions on: +44 (0)20 7040 8611 Editor Shahin Shojai, Global Head of Strategic Research, Capco Advisory Editors Dai Bedford, Partner, Capco Nick Jackson, Partner, Capco Keith MacDonald, Partner, Capco Editorial Board Franklin Allen, Nippon Life Professor of Finance, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Joe Anastasio, Partner, Capco Philippe d’Arvisenet, Group Chief Economist, BNP Paribas Rudi Bogni, former Chief Executive Officer, UBS Private Banking Bruno Bonati, Strategic Consultant, Bruno Bonati Consulting David Clark, NED on the board of financial institutions and a former senior advisor to the FSA Géry Daeninck, former CEO, Robeco Stephen C. -

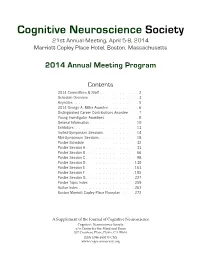

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Michael Finnissy (Piano)

MICHAEL FINNISSY (b. 1946) THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUND CD1: 1 Le démon de l’analogie [28.29] 2 Le réveil de l’intraitable réalité [20.39] Total duration [49.11] CD2: 1 North American Spirituals [23.41] 2 My parents’ generation thought War meant something [35.49] Total duration [59.32] CD3: 1 Alkan-Paganini [13.37] 2 Seventeen Immortal Homosexual Poets [34.11] 3 Eadweard Muybridge-Edvard Munch [26.29] Total duration [74.18] CD4: 1 Kapitalistisch Realisme (met Sizilianische Männerakte en Bachsche Nachdichtungen) [67.42] CD5: 1 Wachtend op de volgende uitbarsting van repressie en censuur [17.00] 2 Unsere Afrikareise [30.35] 3 Etched bright with sunlight [28.40] Total duration [76.18] IAN PACE, piano IAN PACE Ian Pace is a pianist of long-established reputation, specialising in the farthest reaches of musical modernism and transcendental virtuosity, as well as a writer and musicologist focusing on issues of performance, music and society and the avant-garde. He was born in Hartlepool, England in 1968, and studied at Chetham's School of Music, The Queen's College, Oxford and, as a Fulbright Scholar, at the Juilliard School in New York. His main teacher, and a major influence upon his work, was the Hungarian pianist György Sándor, a student of Bartók. Based in London since 1993, he has pursued an active international career, performing in 24 countries and at most major European venues and festivals. His absolutely vast repertoire of all periods focuses particularly upon music of the 20th and 21st Century. He has given world premieres of over 150 pieces for solo piano, including works by Julian Anderson, Richard Barrett, James Clarke, James Dillon, Pascal Dusapin, Brian Ferneyhough, Michael Finnissy (whose complete piano works he performed in a landmark 6- concert series in 1996), Christopher Fox, Volker Heyn, Hilda Paredes, Horatiu Radulescu, Frederic Rzewski, Howard Skempton, Gerhard Stäbler and Walter Zimmermann. -

January 1936) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1936 Volume 54, Number 01 (January 1936) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 54, Number 01 (January 1936)." , (1936). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/840 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. | NEW YEAR JOY IN MUSIC THE SINGER'S ART" by Feodor Chal iapm NEW DITSON PUBLICATIONS CLUB OFFER BjARGAL MS Earn A Teacher’s Diploma (BIG SAVINGS ON ALLY OUR FAVORITE MAGAZINE :s) 1 IMPORTANT ADDITIONS TO MODERN PIANO PEDAGOGY | JUST IN TIME FOR or FOR THE PIANO A Bachelor’s Degree PlR ffi N: EWYEj ROBYN ROTE-CARDS TEACHING MUSICAL NOTATION WITH PICTURE In every community there are ambitious men and women, who know the ROBYN ROTE-CARDS Ri ■NEWA LS! advantages of new inspiration and ideas for their musical advancement, but SYMBOLS AND STORY ELEMENT still neglect to keep up with the best that is offered. They think they are too busy to study instead of utilizing the precious “Tell us a story” has been the cry of humanity since the world began. -

BEYOND BORDERS Essays on Entrepreneurship, Co-Operatives and Education in Sweden and Tanzania

BEYOND BORDERS Essays on Entrepreneurship, Co-operatives and Education in Sweden and Tanzania Edited by Mikael Lnnborg Benson Otieno Ndiege & Besrat Tesfaye BEYOND BORDERS Essays on Entrepreneurship, Co-operatives and Education in Sweden and Tanzania Edited by Mikael Lnnborg Benson Otieno Ndiege & Besrat Tesfaye Södertörns hgskola Sdertrn University Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © the Authors Published under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License Cover layout: Jonathan Robson Cover image (original photograph): Mikael Lönnborg Graphic form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2021 Sdertrn Academic Studies 85 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-89109-61-2 (print) ISBN 978-91-89109-62-9 (digital) Contents 1. Beyond Borders: Entrepreneurship, Co-operatives and Education in Sweden and Tanzania MIKAEL LÖNNBORG, BENSON OTIENO NDIEGE & BESRAT TESFAYE 9 2. Institutional Constraints on Women Entrepreneurship in Tanzania BESRAT TESFAYE, BENSON OTIENO NDIEGE & ESTHER TOWO 51 3. Women’s Entrepreneurial Motives and Perceptions of Entrepreneurship Programmes: A Case Study of Sweden and Tanzania BELDINA ELENSIA OWALLA 83 4. Methodological Insights and Reflections from Studying Venture Teams and Venture Processes in the Contexts of Institutional Transformation TOMMY LARSSON SEGERLIND 109 5. Entrepreneurship in Higher Education Institutions. The Case of University of Iringa, Tanzania BUKAZA CHACHAGE, DEO SABOKWIGINA, HOSEA MPOGOLE, YUSUPH SESSANGA & GABRIEL MALIMA 133 6. Academic Education and Entrepreneurship. A Study of University Graduates in Moshi, Tanzania BLANDINA W. KORI & SAMUEL M. MAINA 151 7. Social Entrepreneurship for Women’s Rights MALIN GAWELL 163 8. Collective Ownership in Sweden – The State, Privatization and Entrepreneurship KARL GRATZER, MIKAEL LÖNNBORG & MIKAEL OLSSON 175 9. -

Click Here to Download the PDF File

THE IMPACT OF THE USE OF INTERNET-BASED TECHNOLOGIES ON NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT PERFORMANCE DANUTA DE GROSBOIS, B.A. (Honours), M.S., M.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management Eric Sprott School of Business Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © Copyright Danuta de Grosbois, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33487-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33487-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

A Selection of Hymns from the Best Authors, Intended to Be an Appendix to Dr. Watts's Psalms and Hymns, by J. Rippon

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 3Z- zsz. 60001 0090G % SELECTION or HYMNS, FROM THE BEST AUTHORS, + INCLUDING A GREAT NUMBER OF ORIGINALS; INTENDED TO BE AN APPENDIX TO DR. WATTS'S PSALMS AND. THE THIRTIETH EDITION. With ahout One Hundred and Fifty Additional Hymns, and Hie Names of the Tunes adapted to most of them. LONDON : PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR, 17, Dot**- Plaet, AW- Kint Bond, AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. JEntnrtr at Stationery' Kali. - . ' c, The Number of the Hymn always answers to the number of the page ; thus— Hymn 33 ....... Page 33 , 433 '- 433 The Number that follows the Names of the Tunes refers to Dr. Rippon's Tune Book ; thus — Hymn 6, Bedford 91 — that is, Tune 91, in the Selection of Tunes. The figures at the foot of the pages give the exact Number of the Hymns, throughout the book, in cluding the different Parts which belong to some of them. R. Clay, Printer, Bread-Slreet-HM. PREFACE ENLARGED EDITION. The Hymns, Original and Selected, which are interspersed through this Edition, appear before the Religions Public with no higher ambition than of being, in some measure, of the humble and happy FAMIL,Y, which, through the astonishing goodness of the God of Providence and Grace, have met the fa vourable acceptance of more than TWO HUNDRED THOUSAND PERSONS, chiefly in this country ; saying nothing of the numerous Editions through which the Work has passed in America.* This circumstance, • Just after the first edition of this Preface was printed, I received a pleasi : ; letter from Philadelphia, informing me of tbe good acceptance of the Selection in America, and of the IV PREFACE. -

BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 556843 Ii ABSTRACT Vo

JERZY KOS INSKI I A STUDY OP HIS NOVELS David J. Lipani A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1973 BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 556843 ii ABSTRACT Vo. The Introduction examined relevant aspects of Kosin ski’s life in an attempt to establish a relationship between his past experiences and the major themes of his fiction. It was discovered that the author’s exposure to diverse forms of authoritarian control constituted the source of his bias against any external force operating counter to the self’s freedom. The four novels comprising the Kosinski canon were analyzed in detail, especially as they were directed toward the quest for a viable self in a contemporary world threatening to submerge the individual consciousness. Each protagonist was shown struggling with some variant of social repression» the boy in The Painted Bird faced hostile peasants who, swayed by Nazist ideology, viewed him as a menace to their own safety» the narrator in Steps fled the socialist bloc because there he had no control of his destiny, nor was his being acknowledged as an entity separ ate from the masses» Chance, in Being There, was subjected to a more insidious totalitarianism--the television medium, whose false representation of reality effectively kneads the individual into an easily manipulated, mindless soul» and Jonathan Whalen, in The Devil Tree, fell victim to the Protestant Ethic, the demands of which left him unable to see himself as something other than an image occasioned by wealth and status. -

CATCHING the LONG TAIL Labels Eye Profits from the Old & the Niche

DIGITAL BEATLES ?! Can A China Biz Go Legit? >P.6 SCH 3 907 #BXNCTCC * * * *' *" F'F " -___ -DIGIT IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIII I II11111 #BL2408043# APR06 REG A04 B0105 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 R MAR FOR MORE THAI 110 YEARS 4 2006 CATCHING THE LONG TAIL Labels Eye Profits From The Old & The Niche. But Is It Worth The Headache? >P.22 DIGITAL ALBOOM Jack Johnson's Record - Breaking Week >P.5 NE -YO'S RISE From Secret Songwriter To Top Star > P.39 TOURING BIZ BATTLES 99US 18.99 AN SECONDARY TIX 09> Why Let The Spoils Go To eBay? >P.24 1 11 0 74470 02552 8 www.billboard.com www.billboard.biz US $6.99, CAN $8.99, £ £5 ©PE 8.95, JAPAN V2,500 www.americanradiohistory.com UNFORGETTABLE MUSIC AND A NIGHT TO REMEMBER! Andy Lack, Tom Corso, Barry Weiss, Clive Davis, Fergie, Kelly Clarkson, Sheryl Crow, Sharon Stone, Dido Santana, Sa a Hayek, Joe Perry, Steven Tyler Jim Urie, Doug Morris, LA Reid Rolf Schmidt-Holtz , Charles Goldstuck, Richard Palmese Natalie Cole, Alicia Keys, Diana Ross, Lyor Cohen, Russell Simmons, Jay Z Clive Davis, Mary J. Blige, Jamie Foxx Terrence Howard, Babyface, Gabrielle Union Beyoncé, Ciara r Ouincy Jones, Ahmet Ertegun, Clive Davis, Pharrell Williams, Kanye West, Billy F. Gibbons of ZZ To , Brian Wilson, Burt Mica Ertegun Chad Hugo, Ludacris Bacharach, David Foster, Dusty Hill of ZZ Top w Pat O'Brien, Larry King, Julie Chen, Allen Grubman, Paul McGuinness, Kelly Curtis Cameron Crowe, Rob Thomas, Courtney Love, Jon Voight, Denise Rich, Barbara Davis, Wolfgang Puck Les Moonves, Neil P-tnow, Craig Ferguson and Benny Medina Brett Ratner, Dave Grohl Scott Weiland of Velvet Ivolver, The Dixie Chicks, Paul Stanley, Snoop Dogg, Gene Simmons, Fantasia, Carrie Underwood, Bo Bice Quincy Jones, Clive Davis, Ludacris and Charles Matt Jelvet Sorurn of Revolver Evander Holyfield Goldstuck join Hugh Panero, CEO of XM Satellite Radio ALL STAR PERFORMANCES THAT WILL NEVER BE FORGOTTEN! Charles Goldstuck thanks the right's LA Reid movingly introduces host MC for the night, Clive Davis. -

What Makes Entrepreneurs Entrepreneurial?

What makes entrepreneurs entrepreneurial? Saras D. Sarasvathy Associate Professor The Darden Graduate School of Business Administration University of Virginia [email protected] What makes entrepreneurs entrepreneurial? Professionals who work closely with them clear in the next section, I have termed this type and researchers who study them have often of rationality “effectual reasoning”. speculated about what makes entrepreneurs “entrepreneurial”. Of course, entrepreneurs also Effectual reasoning: The problem love to hold forth on this topic. But while there The word “effectual” is the inverse of are as many war stories and pet theories as there “causal”. In general, in MBA programs across are entrepreneurs and researchers, gathering the world, students are taught causal or together a coherent theory of entrepreneurial predictive reasoning – in every functional area expertise has thus far eluded academics and of business. Causal rationality begins with a practitioners alike. pre-determined goal and a given set of means, What are the characteristics, habits, and and seeks to identify the optimal – fastest, behaviors of the species entrepreneur? Is there cheapest, most efficient, etc. – alternative to a learnable and teachable “core” to achieve the given goal. The make-vs.-buy entrepreneurship? In other words, what can decision in production, or choosing the target today’s entrepreneurs such as Rob Glaser and market with the highest potential return in Jeff Bezos learn from old stalwarts such as marketing, or picking a portfolio with the lowest Josiah Wedgwood and Leonard Shoen? Or even risk in finance, or even hiring the best person for within the same period in history, what are the the job in human resources management, are all common elements that entrepreneurs across a examples of problems of causal reasoning. -

December 26, 1889

B u c h a n a n R e c o r d . Lo ok Here J ?CTBUSHED EVERY THURSDAY, Having again engaged in the —BY— T O m S F Q.HOI jMES. TERMS, SI.SO PER YEAR R ecord. PAYABLE JIT ADVANCE. AWERTIS1US RATES Mfti Ki® 08 APPUC&TICU. NUMBER 48. volume xxm . llrif'H AX A \ BERRIEN COUNTY, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY. DECEMBER 26, 1889. In Buchanan, (at Cathcart’s Old Gallery), OFFICE—InRecordBuiiaing.QakStreet I will be pleased to see all my old THE MEN WHO'MISS THE XBAIN. Some Curious Wills. It may be you will love her yourself, hole of my doublet. Will that satisfy friends at the above place. j my Charles.” you of our good understanding ?” BV s. W. VOSS. The St. Louis Republic, some time READY FOR THE “It may be,” replied Westleigh, com Speechless with rage, Charles replied ago, had a chapter on wills; showing !3 easiness Directory. I loafe a’ onu’ the deepo jest to see the Pull placently. “You promise me, then, by a fierce gesture and strode toward the testators to have possessed minds man scoot, that you will woo my sister only, and liis sister, followed by the page, beneath SABBATH SERVICES. singularly constituted. An’ to soothe people scamper w’en thcylioar not my cousin ?” whose mask could beperceived a sud Often quoted is the remarkable-will 'ERVICES arc field every Ssablmfc at 10:30 the ingine toot; den access of color. Coming dose to A o’clock a. s., at the Cluircli or the “ Larger “I swear it to you, Charles.” b lint w’at makes the most impression on my of Solomon Sanborn, of Medferd,Mass., iopu 'i” also, Sabbatli School services iramecliatc- Snowball, whose eyes had expanded the Iady-in:waiting, who was carrying who died about fifteen years ago. -

Diary of a Dirty Computer Janelle Bullock

Diary of a Dirty Computer _______________________________________________________ Janelle Bullock, McNair Scholar, The Pennsylvania State University McNair Research Faculty Adviser: Timeka Tounsel, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Media Studies The Pennsylvania State University Abstract This paper explores how contemporary Black women artists use audiovisual resources and experimental forms of musical storytelling to construct a 21st century critical Black feminist mode of expression. Specifically, I examine Janelle Monáe and her visual album Dirty Computer. Using textual analysis and semiotic analysis, I approach Dirty Computer as a case study that demonstrates how Janelle Monáe, a Queer Black woman, uses commercial media as a platform for self-definition. Furthermore, my project is an autoethnography that considers my own experiences of the tensions that emerge in an attempt to make sense of the self as a Queer Christian Black woman. Introduction Artists like Michael Jackson and Prince were well-known for integrating audiovisual elements into their work as music artists. Thriller (1982) and Purple Rain (1984) were more than musical triumphs, they were multimedia projects that thrust Jackson and Prince into superstardom. In fact, Purple Rain garnered an Oscar and two Grammy awards for its artistry and Thriller was a groundbreaking masterpiece that helped to integrate the MTV network, especially its 14-minute music video for the song that shared the album’s title. By experimenting with artistic storytelling across different platforms, Prince and Jackson set the tone for an important genre in black expressive culture—the music video—that would eventually become dominated by hip-hop artists. By the 1990s, music industry gatekeepers repackaged hip-hop as a heavily masculine, hypersexual, and aggressive genre steeped in stereotypes of black criminality and caricatures of the black poor.