Green Snail by Masashi Yamaguchi FFA Report 92/61

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periwinkle Fishery of Tasmania: Supporting Management and a Profitable Industry

Periwinkle Fishery of Tasmania: Supporting Management and a Profitable Industry J.P. Keane, J.M. Lyle, C. Mundy, K. Hartmann August 2014 FRDC Project No 2011/024 © 2014 Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-86295-757-2 Periwinkle Fishery of Tasmania: Supporting Management and a Profitable Industry FRDC Project No 2011/024 June 2014 Ownership of Intellectual property rights Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies. This publication (and any information sourced from it) should be attributed to Keane, J.P., Lyle, J., Mundy, C. and Hartmann, K. Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, 2014, Periwinkle Fishery of Tasmania: Supporting Management and a Profitable Industry, Hobart, August. CC BY 3.0 Creative Commons licence All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence, save for content supplied by third parties, logods and the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. The full licence terms are available from creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode. Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of this document should be sent to: [email protected]. Disclaimerd The authors do not warrant that the information in this document is free from errors or omissions. -

Appendix C: Open Literature Studies Located in ECOTOX Search

Appendix C: Open Literature Studies Located in ECOTOX Search The ECOTOX database is developed and maintained by EPA’s National Health and Environmental Effects Research laboratory, Mid-Continent Ecology Division (MED) in Duluth, Minnesota. Studies located using the ECOTOX database are grouped into the following three categories: Studies which are excluded from ECOTOX, studies accepted by ECOTOX but not OPP, and studies accepted by ECOTOX and OPP. Generally, studies are excluded from ECOTOX because the contain information about the chemical, but not effects data. (e.g., fate studies, monitoring studies, chemical methods). Studies containing effects data are encoded into ECOTOX by trained document abstractors at MED, and this group of papers comprises the studies accepted by ECOTOX category. The final category of accepted by ECOTOX and OPP is determined using specific criteria described on the following page. Data from the category of studies accepted by ECOTOX and OPP may be used in the risk assessment. ECOTOX studies used in the assessment are listed both in this appendix and in the bibliography in the main document. Studies acceptable to ECOTOX and OPP that are not incoporated into the assessment generally either 1) produce a less sensitive endpoint than the ones used in the assessment, or 2) do not address organisms of concern for this assessment. The ECOTOX database has been searched twice for information regarding metolachlor, once in September 2004, and again in August 2006. Papers in each category are separated by search date. The 2006 search considered data encoded following the initial search date. Data in papers located by ECOTOX includes both racemic metolachlor (PC#108801) and s-metolachlor (PC#108800). -

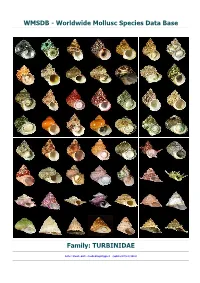

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Reproductive Biology of Two Species Congregation of Adults in Groups Clearly Ensures the of Turbinidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda)

World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences 2 (1): 14-20, 2010 ISSN 2078-4589 © IDOSI Publications, 2010 Annual Cycle of Reproduction in Turbo brunneus, from Tuticorin South East Coast of India 1R. Ramesh, 2S. Ravichandran and 2K. Kumaravel 1Department of Zoology, Government Arts College, Salem, India 2Centre of Advanced Study in Marine Biology, Annamalai University, India Abstract: This research work mainly focus on the reproductive and spawning season of Turbo brunneus a mollusk in the south east coast of India. Random samples from Turbo brunneus were collected from littoral tidal pools in Tuticorin coast, during May 2002 to April 2003. The number of male and females in the monthly samples was counted to determine the male: female ratio in the population and chi-square test was applied to test whether the population adheres to 1:1 ratio. The overall male and female ratio is found to be 1: 0.96 indicating only a slight variation in the evenness of male and female in the population. Both sexes of T. brunneus attain sexual maturity between 23 and 27mm. The mean gonadal index (G.I) was high (21.82%) in males during May, 2002 and then it decreased gradually and reached 15.52% during October 2002, which showed the low mean GI value in males for the whole study period. While for females it was high during May 2002 (23.09%) and low during September 2002(14.83%). The GI values for both the sexes were generally low until December 2002. The limited percentage of matured oocytes which exists even after spawning indicates the high possibility for partial spawning in T. -

IMPACTS of SELECTIVE and NON-SELECTIVE FISHING GEARS

Histological study of gonadal development of Turbo coronatus (Gmelin, 1791) (Gastropoda: Turbinidae) from Karachi coast, Pakistan Item Type article Authors Afsar, Nuzhat; Siddiqui, Ghazala Download date 24/09/2021 00:12:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40808 Pakistan Journal of Marine Sciences, Vol. 25(1&2), 119-130, 2016. HISTOLOGICAL STUDY OF GONADAL DEVELOPMENT OF TURBO CORONATUS (GMELIN, 1791) (GASTROPODA: TURBINIDAE) FROM KARACHI COAST, PAKISTAN Nuzhat Afsar and Ghazala Siddiqui Institute of Marine Science, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan (NA); Center of Excellence in Marine Biology, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270 (GS). email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Gonadal developmental stages and temporal trends of the Turbo coronatus were determined over one year study period during August 2005 to July 2006 in populations inhabiting rocky shores of Buleji and rocks of seawall at Manora Channel, coastal areas of Karachi. Studies were based on histological examination of gonads as well as Turbo populations at two sites found in spawning state throughout the year. The gonads of Turbo coronatus at both localities were never found in completely spent condition, thus suggesting that they are partial spawners. Generally, it appears that spawning in males and females of T. coronatus at Manora channel is slightly asynchronous as compared to Buleji where spawning pattern seems to be more synchronous. Oocytes diameter in specimen of this species at Manora was significantly larger than that of specimens studied from Buleji (ANOVA: F=6.22; P<0.05). The overall sex-ratio was close to 1:1 theoretical ratio at both of the sites. -

Templat Tesis Dan Disertasi

1 I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Siput mata bulan (Turbo chrysostomus) merupakan salah satu organisme invertebrata yang cukup potensial untuk dikembangkan karena bernilai ekonomis tinggi dan memiliki daya tahan tubuh yang cukup baik terhadap perubahan lingkungan (Setyono et al. 2013). Terdapat beberapa jenis dari genus Turbo di Dunia antara lain T. agyrostomus, T. brunneus, T. cinereus, T. cornutus, T. intercostalis, T. marmoratus, T. petholatus, T. radiatus, T. sarmaticus, T. setosus, T. smaragdus, T. torquatus dan beberapa jenis lainnya (Ruf 2007; Ubaidillah et al. 2013) namun yang lebih potensial dikembangkan di Indonesia adalah jenis T. marmoratus dan T. chrysostomus (Dwiono et al. 2001). Seperti jenis grastopoda lainnya, siput mata bulan dilengkapi dengan sekeping cangkang yang berfungsi untuk melindungi organ lunaknya dari incaran predator. Siput ini dikenal dengan nama internasional yellow-mouth turban atau gold-mouth turban dan di Indonesia dikenal sebagai siput bulan (Ambon), siput mata lembu (Pelabuhan Ratu dan Pangandaran, Jawa Barat) (Arifin 1994) dan sisok matan terata (Lombok). Siput mata bulan dapat ditemukan di wilayah perairan Indo-Pasifik termasuk perairan pesisir Samudra Hindia (Kenya, Eychelles, Chagos, Andaman dan Pulau Nicobar), Asia Tenggara (Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand dan Filipina) dan Kepulauan Fiji Selatan. Jenis siput ini juga ditemukan di perairan pesisir Kepulauan Ryukyu Jepang, dan di perairan Melanesia Utara hingga Kaledonia Baru Selatan (Soekendarsi 2018). Siput mata bulan ditangkapi masyarakat setempat, dikarenakan rasanya yang gurih dan memiliki kandungan gizi yang cukup tinggi. Setyono (2006) mengemukakan bahwa kerang dan siput memiliki kandungan protein yang sangat tinggi yaitu lebih dari 50%. Siput T. setosus memiliki kandungan protein 63,37%, karbohidrat 27,01%, mineral (K, Mg, Fe, Zn), asam amino (arginin, asam glutamat), dan lemak 0,08% (berdasarkan berat kering) (Merdekawati 2013). -

Iv Edible Gastropods

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by CMFRI Digital Repository IV EDIBLE GASTROPODS K. S. SUNDARAM Marine gastropods form the largest group of species in the phylum Mollusca in shallow seas. Of these only a small number of species are suitable for being utilized as food by man. The univalves are fished in many parts of the world for bait, for their beautiful shells and manufacture of lime. Since the animals are passive, simple methods are used in collecting them. The edible gastropods limpets, trochids, whelks, the sacred chank {Xancus pyrum), olives {Oliva spp.), the green snail (Turbo) etc. are represented in difi'erent regions of the Indian coasts in the intertidal zone and shallow waters. They are fished by fishermen and poor coastal people for food usually when fish are not available. In India the above mentioned edible gastropods are generally collected for their shells which are cleaned, polished and sold as ornamental articles. Gastropods are seldom sold in the markets for being used as food. The button-shell Umbonium vestiarium is the only species that finds a place in fish- stalls in Malwan in Maharashtra. The habits, ecology and economics of the edible gastropods of Indian coasts have been dealt with by Hornell (1917, 1951). Rai (1932), Setna (1933), Rao (1939, 1941) and Rao (1958, 1969) have made contributions on the shell-fish and their fisheries in general and stressed the importance of the shell-fish in the eco nomy of the fishermen. The descriptions of a number of commercial gastropods have been given by Satyamurthi (1952). -

A Comparative Study of Population Structure and Condition Index of Two Species of Gastropod Molluscs from Exploited and Non-Exploited Sites of Karachi Coast

INT. J. BIOL. BIOTECH./, 3 (1): 31-37, 2006. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF POPULATION STRUCTURE AND CONDITION INDEX OF TWO SPECIES OF GASTROPOD MOLLUSCS FROM EXPLOITED AND NON-EXPLOITED SITES OF KARACHI COAST Solaha Rahman1 and Sohail Barkati 2 1M.A.H. Qadri, Biological Research Centre, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan 2Department of Zoology, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The condition index of two abundant gastropod species of Turbo (T. coronatus and T. intercostalis) from exploited and non-exploited sites of Karachi was studied on monthly basis, for a period of one year from October 2004 to September 2005. A significant difference in condition index of two species from exploited and non-exploited sites was demonstrated. Condition index values were relatively higher and less varied throughout the year in both the species of Turbo at less polluted and non-exploited site (Nathiagali) as compared to polluted and exploited site (Buleji). The two sites also differed in the period of highest and lowest condition index values of standard size snails of both species of Turbo. An inverse relationship between condition index and shell height of snails was noted for most of the year in both the species. The results are discussed with reference to their presence under different environmental conditions. Key-words: Pollution, exploited, Condition Index, Gastropod species. INTRODUCTION Gastropod molluscs are one of the most abundant groups of marine invertebrates on the rocky beaches around Karachi. They are important not only because they are available in large number and hence deserve attention, but also some of them grow to large size and thus may be utilized for their meat (soft tissue). -

India of Arabian Sea

6 I January 2018 http://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2018.1252 International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET) ISSN: 2321-9653; IC Value: 45.98; SJ Impact Factor :6.887 Volume 6 Issue I, January 2018- Available at www.ijraset.com Intertidal Macrofaunal Invertebrates Diversity from Ratnagiri Coast, (MS) India of Arabian Sea Vijay R. Lakwal1, Dinesh S. Kharate2, Satish S. Mokashe3 Department of Zoology, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad, (M.S.) India Abstract: The diversity of intertidal macrofaunal invertebrates from rocky substrata of Ratnagiri coast was studied during March 2015 to February 2017. A total 83 species were identified representing 6 phyla, belonging to12 classes, 34 orders and 50 families were recorded from Ratnagiri coast. Results showed that mollusca exhibited highest contribution with 46 species with 55% of the total diversity. Phylum porifera appeared as the second most dominant group contributed 12 species with 15% diversity, Coelenterates comprised 10 species with 12% and Arthropods contributed 10 species with 12% diversity, Echinodermata 3 species with 4% and last Annelids 2 species with 2% of the total diversity. The diversity of macrofaunal group in prevalence of different habitats a wide chance of research to further explore on the possibility of ecological value and there conservation. Keywords: Diversity, Intertidal zone, Macrofaunal assemblage, Ratnagiri Coast. I. INTRODUCTION The intertidal zone of any ecological area is considered as the most productive with the greatest diversity of plant and animal life. Because of its accessibility, the intertidal zone remain highly explored than any other area (Vaghelaet al., 2010). Rocky shores are the most extensive littoral habitats exposed to eroding waves and thus are ecologically very important (Crowe, et al., 2000). -

Secretion of Embryonic Envelopes and Embryonic Molting Cycles In

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE. 64(2): 269-280, 1999 THE PEA CRAB ORTHOTHERES HALIOTIDIS NEW SPECIES (DECAPODA: BRACHYURA: PINNOTHERIDAE) IN THE AUSTRALIAN ABAhONEHALIOTISASININA LINNAEUS, 1758 AND HALIOTIS SQUAMATA REEVE, 1846 (GASTROPODA: VETIGASTROPODA: HALIOTIDAE) Daniel L. Geiger and Joel W. Martin ABSTRACT A new species of pinnotherid crab, Orthotheres haliotidis, is described from two spe cies of Australian abalone, Haliotw asin'ma Linnaeus, 1758, and H. squamata Reeve, 1846. Its morphology is recorded using light and scanning electron microscopy. The re port is the second record of the predominantly American genus Orthotheres in the west- em Pacific, the firet confirmed record of a pinnotherid crab from any species of abalone, and the first record of a pinnotherid associated with H. squamata. Commensalisms between pea crabs (Brachyura: Pinnotheridae) and various inverte brates are fairly well known and documented; Schmitt et al. (1973) listed as hosts 10 phyla from Cnidaria to Chordata: Ascidia. Pea crabs have been found within the Mollusca in one chiton, 19 prosobranchs (Table 1), four opisthobranchs and in 182 bivalves. Since then a number of additional associations between pea crabs and mollusks have been de scribed notably most with bivalves (Bhavanarayana and Devi, 1974; Fischer and Fischer- Piette; 1976, Konishi, 1977; Stevens, 1992; Zmarzly, 1992; Campos, 1993; Schneider, 1993; Korkos and Singer, 1995), however, only one with a further gastropod host (Cam pos, 1989: table 1). In abalone only a few commensals are known. The association between the alpheid shrimp Betaeus harfordi (Kingsley, 1878) with all six California abalone species has been described (Cox, 1962; Chace and Abbott, 1980; Jensen, 1995). -

Molluscan Fauna from San Francisco Bay

-. V.. .... p .: jyp'p. ~^s. usnmII Wvision of Mblii Sectiooal Library /'UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN ZOOLOGY Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 199-452, pis. 14-60 September 12, 1918 ¥ MOLLUSCAN FAUNA FROM SAN FRANCISCO BAY E. L. PACKARD 4i R UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY UNIVERSITY OF 0ALD70BNIA PUBLICATIONS Note.—The University of California Publications are offered in exchange for the publi- cations of learned societies and institutions, universities and libraries. Complete lists of all the publications of the University will be sent upon request. For sample copies, lists of publications or other information, address the MANAGER OF THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA, U. S. A. All matter sent in exchange should be addressed to THE EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT, UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA, U.S.A. WILLIAM WESLEY & SONS, LONDON Agent for the series in American Archaeology and Ethnology, Botany, Geology, Physiology, and Zoology. ZOOLOGY.—W. E. Bitter and C. A. Kofoid, Editors. Price per volume, $3.50; beginning with vol. 11, $5.00. This series contains the contributions from the Department of Zoology, from the Marine Laboratory of the Scripps Institution for Biological Research, at La Jolla, California, and from the California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology in Berkeley. Cited as Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. Volume 1, 1902-1905, 317 pages, with 28 plates „ _ $8.50 Volume 2 (Contributions from the Laboratory of the Marine Biological Association of San Diego), 19041906, xvii + 882 pages, with 19 plates $3.50 Volume 3, 1906-1907, 383 pages, with 23 plates _ $3.50 Volume 4,. 1907-1908, 400 pages, with 24 plates : _ $3.60 Volume 5, 1908-1910, 440 pages, with 34 plates . -

Distribution-And-Diversity-Of-Shellfishes-Along-The-Intertidal-Rocky-Coast-Of-Veraval-Gujarat

IJSAR, 2(9), 2015; 33-39 International Journal of Sciences & Applied Research www.ijsar.in Distribution and diversity of Shellfishes along the intertidal rocky coast of Veraval, Gujarat (India) T.H. Dave3*, B.G. Chudasama1, A.S. Kotiya2, A.J. Bhatt3, D.T. Vaghela4 1Department of Harvest and Post-Harvest, College of Fisheries, JAU, Veraval, Gujarat, India, 2Agricultural Research Station, JAU, Mahuva, Gujarat, India, 3Department of Fisheries Resource management, College of Fisheries, Junagadh Agricultural University (JAU), Veraval, Gujarat, India. 4Department of Aquatic Environment, College of Fisheries, JAU, Veraval, Gujarat, India. Correspondence Address: *T.H. Dave, Department of Fisheries Resource Management, College of Fisheries, Junagadh Agricultural University (JAU), Veraval, Gujarat, India. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The rocky intertidal coast of veraval harbours a good number of seaweeds and shellfish diversity. The vertical exposed coastal length of 60-70 meter were divided into three different zones from the highest high tide line. The zones were Zone-1 (0-20mt), Zone-2 (20-40mt), and Zone-3 (40- 60mt). The highest density of organisms found at Zone-2, followed by Zone-3 and Zone-1. The coast inhabits 33 species of shellfishes of which 28 were molluscs and 05 crustaceans. It is also observed that the most abundant and year round species observed was Patella radiate followed by Turbo intercostalis, Chiton granoradiatus, Rinoclavis sinensis and Cerithium spp. of molluscs and Balanus amphtrite among the crutaceans. The shellfishes like Hexaplex endivia, Pyrene versicolor, Anadara Spp., Murex tribulus and Chicoreus ramosus shown rare availability at almost all the level. The seawater parameters recorded were: pH – 8.2 to 8.32, Temperature – 28 to 310C, Salinity – 34.1 to 35.5 ppt, and Dissolved Oxygen – 4.8 to 5.9 mg/l.