Women's Mixed Martial Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brian Sandoval Governor STATE OF

Bruce Breslow Brian Sandoval STATE OF NEVADA Department Director Governor DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY ATHLETIC COMMISSION Bob Bennett Executive Director Chairman: Anthony A. Marnell III Members: Francisco V. Aguilar, Skip Avansino, Pat Lundvall, Michon Martin TO THE COMMISSION AND THE PUBLIC: AGENDA A duly authorized meeting of the Nevada State Athletic Commission will be held on Wednesday, February 17, 2016, at 9:00 a.m. at the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, 555 East Washington Avenue, Room 4500 Las Vegas, NV 89101. 1. Call to order. 2. Roll Call. 3. Public Comment. 4. Approval of the minutes of the meetings of December 17, 2015 and February 4, 2016 for possible action. 5. Adoption of the agenda for this meeting, for possible action. 6. Disclosures per NRS 281/281A. OLD BUSINESS: 1. Re‐hearing on appropriate discipline against mixed martial artist Wanderlei Silva, for possible action. CONSENT AGENDA: a. Date Requests 1. Request by Roy Englebrecht Promotions for the date of March 12, 2016 to promote a boxing event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on CBS Sports Network with a maximum of 7 fights and pending Executive Director Bob Bennett’s approval of the venue’s outdoor facilities, for possible action. 2. Request by World Series of Fighting for the date of April 2, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on NBC Sports Network, for possible action. 3. Request by Zuffa, LLC for the date of April 23, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas to be televised on PPV, for possible action. -

Political Views an Unjust Reason to Cancel

Page 8 FORUM Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Political views an unjust reason to cancel Today’s and criticism to Disney and Reporter, a source from Generation contributed to recent debates Lucasfilms said, “They have Hallie Funk on “cancel culture.” been looking for a reason to fire Several celebrities, actors, her for two months, and today and political figures have been was the final straw.” The “final Last October, actress Gina involved in these series of straw” was when Carano posted Carano stepped onto the “cancelling,” including Ellen a tweet that compared Jewish Disney+ screen as Cara Dune, DeGeneres, J.K. Rowling, and people in the Holocaust to the new female lead of the Johnny Depp. An individual is Republicans in America’s current hit show, The Mandalorian. typically “canceled” when the political climate. Although this As the season started, many public or media disagrees with is an extreme comparison that praised her acting abilities and a certain decision or belief the is not truly accurate, it is not accepted Carano as the perfect person has and chooses to stop a fireable offense. Her general cast for the role. She brought supporting them. It can be a point was not inappropriate, body positivity to the screen, result of accusations, negative but the Holocaust comparison and portrayed women as strong media coverage, or social media was. Which brings to question, and independent. But as of last posts, as in Carano’s case. are inappropriate comparisons month, she will no longer be a The controversy began back fireable offenses? part of Disney or her employing in November when Carano In June 2018, Pedro Pascal, agency. -

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Match Results

Match Results Date: 4/19/2014 Venue/Location: Amway Center -- Orlando, FL Promoter: UFC Commissioners Judge: Richard Bertrand Referee: John McCarthy Physician: Dr. Adam Brunson Commissioners Judge: Chris Lee Referee: Jorge Alonso Physician: Dr. George Panagakos Dr. Mark Williams, Chairman Judge: Jean Warring Referee: Jorge Ortiz Knockdown Timekeeper: Dr. Wayne Kearney Judge: Eliseo Rodriguez Referee: Herb Dean Alternate Referee Mr. Antonius DeSisto Judge: Hector Gomez Referee: Commissioners Present: Mr. Marco Lopez Judge: Tim Vannatta Referee: Mr. Tirso Martinez Judge: Derek Cleary Referee: Referee: Executive Director: Cynthia Hefren Asst. Executive Director: Frank Gentile Timekeeper(s): James Chittenden; Roy Silbert Event Type: MIXED MARTIAL ARTS Participants Federal ID Hometown Weight DOB Sch Rds Results Officials Suspensions and Remarks Claim form, knee, indefinite susp, neruo Referee: John McCarthy; Jack May 110-622 Costa Mesa, CA 252.5 lbs 4/14/1981 clearance 3 Judges: Jean Warring; Chris 1 Winner TKO 4:23 1st Lee; Richard Bertrand Referee stoppage from strikes Derrick Lewis 116-645 Houston, TX 256.0 lbs 2/7/1985 Rd Referee: Jorge Ortiz; Judges: Chas Skelly 101-842 Keller, TX 145.0 lbs 5/11/1985 2 3 Eliseo Rodriguez; Tim Winner by Majority Vannatta; Richard Green Suspension 180 days or Facial CT Marsid Bektic 105-060 Coconut Creek, FL 146.0 lbs 2/11/1991 Decision clearance Referee: Jorge Alonso; Ray Borg 127-020 Albuquerqu, NM 125.5 lbs 8/4/1993 3 3 Judges: Chris Lee; Hector Winner by Split Gomez; Derek Cleary Dustin Ortiz 121-691 -

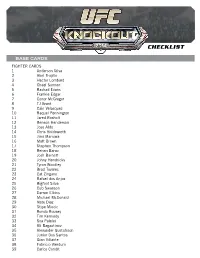

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

Universal Sales & Service Ltd

- ---' ','" ,- {C'.: ',,,_/. ,",:,.- _ .' c. " • .-~- - '-'~" . ".- I _t'r: ., ' Page Five . r-: 7""~~: --_._-----,------ --_ .. _.- "," " ','; ~ THE. JEWISH POST - ~ .. ~' Thur~day, July 5, 1951 .. Thursday, July 5, 1951 / highlighted hy the presentation of \ ports of activities. during the past c~rtificate awards and gifts and re- year.. (See page 6.) .- THE JEWISH POST Hold Annivesary Windup: Lorne Pearlman,. so'n of Mr. and - p~ge Four Consulate General at 1260 Univer Dr. C. D. Rusen Heads Mrs. J. Pearlman, has returned from the Israel Ministry Education, ~eabstone of sity Street, Montreal, so that tbe Shaarey Zedek Scene of Levy.Myers Wedding Alpha Omega Dental portland, Ore., to visit here for the thei Consulate General of Israel in Twin Chapters' Windup necessary fonns can be forwarde-d 1t summer. He is attending the Uni Canada requests all Israeli stu The Shaarey Zedek Fraternity Wnbeiling versity of Oregon Dental College. dents to contact the office of the to them. SOCIAL AND synagogue was the col .. At a recent meeting of the Alpha orful setting of the after Omega Dental fraternity, Dr. Chas. The Family 91 the Late Jsaac Y urman Passes , . "YOU'LL ENJOY SHOPPING .ATGOLDEN'S" noon wedding of Audrey Rusen was elected president for the Entirety Air Conditioned jar Your Comfort PERSONAL Roslyn, only daughter of coming year. Other officers elected Suddenly, Aged 68 MRS. ROSE Mrs. G. Myers, and ISAACOVITCH Mr. and Mrs. Sydney Robinson, are: Isaac Yunnan, 329 Burrows ave I. Sheldon, oniy son of' Immediate past president, Dr. H. 334 Wellington crescent, announce nue, passed· away Sunday night, requests all their relatives and Mrs. -

The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport

Journal of Sport Management, 2017, 31, 533-545 https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0333 © 2017 Human Kinetics, Inc. ARTICLE The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport T. Christopher Greenwell University of Louisville Jason M. Simmons University of Cincinnati Meg Hancock and Megan Shreffler University of Louisville Dustin Thorn Xavier University This study utilizes an experimental design to investigate how different presentations (sexualized, neutral, and combat) of female athletes competing in a combat sport such as mixed martial arts, a sport defying traditional gender norms, affect consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, event, and athlete brand. When the female athlete in the advertisement was in a sexualized presentation, male subjects reported higher attitudes toward the advertisement and the event than the female subjects. Female respondents preferred neutral presentations significantly more than the male respondents. On the one hand, both male and female respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was more attractive and charming than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and more personable than the fighter in the combat ads. On the other hand, respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was less talented, less successful, and less tough than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and less wholesome than the fighter in the neutral ad. Keywords: brand, consumer attitude, sports advertising, women’s sports February 23, 2013, was a historic date for women’s The UFC is not the only MMA organization featur- mixed martial arts (MMA). For the first time in history, ing female fighters. Invicta Fighting Championships (an two female fighters not only competed in an Ultimate all-female MMA organization) and Bellator MMA reg- Fighting Championship (UFC) event, Ronda Rousey and ularly include female bouts on their fight cards. -

Ufc Fight Night Features Exciting Middleweight Bout

® UFC FIGHT NIGHT FEATURES EXCITING MIDDLEWEIGHT BOUT ® AND THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE ON FOX SPORTS 1 APRIL 16 Two-Hour Premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER: TEAM EDGAR VS. TEAM PENN Follows Fights on FOX Sports 1 LOS ANGELES, CA – Two seasons of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER® converge on FOX Sports 1 on Wednesday, April 16, when UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: BISPING VS. KENNEDY features THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS welterweight and middleweight finals, the coaches’ fight and an exciting headliner between No. 5-ranked middleweight Michael Bisping (25-5) and No. 8- ranked Tim Kennedy (17-4). FOX Sports 1 carries the preliminary bouts beginning at 5:00 PM ET, followed by the main card at 7:00 PM ET from Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. Immediately following UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BISPING VS. KENNEDY is the two-hour season premiere of THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER®: TEAM EDGAR vs. TEAM PENN (10:00 PM ET), highlighting 16 middleweights and 16 light heavyweights battling for a spot on the team of either former lightweight champion Frankie Edgar or two-division champion BJ Penn. UFC on FOX analyst Brian Stann believes the headliner between Bisping and Kennedy is a toss-up. “Kennedy has one of the best top games in mixed martial arts and he’s showcased his knockout power in his last fight against Rafael Natal. Bisping is one of the best all-around mixed martial artists in the middleweight division. Every time people start to count him out, he comes in and wins fights.” In addition to the main event between Bisping and Kennedy, UFC FIGHT NIGHT consists of 12 more thrilling matchups including THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER NATIONS Team Canada coach Patrick Cote (20-8) and Team Australia coach Kyle Noke (20-6-1) in an exciting welterweight bout. -

Grappling with Gender and Hypermasculinity in Mixed Martial Arts Program Authorized to Offer Degree

Position Before Submission: Grappling with Gender and Hypermasculinity in Mixed Martial Arts Courtney C. Choi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Natalie Jolly, Chair Lawrence M. Knopp Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences © Copyright 2017 Courtney C. Choi University of Washington Abstract Position Before Submission: Grappling with Gender and Hypermasculinity in Mixed Martial Arts Courtney C. Choi Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Natalie Jolly, Ph.D. School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences The intent of this thesis is to explore existing gender norms in mixed martial arts cultures. Masculinity is particularly valorized in sport, creating tension for female athletes who are forced to balance masculine norms with feminine beauty ideals. While there is a robust literature on the intersections of mixed martial arts (MMA) and masculinity, female voices are rarely heard in that literature. My research goes beyond the work of others by incorporating female voices and perspectives. Grounded in gender constructionism, my thesis addresses how both male and female MMA fighters conceive of their and others’ participation in gendered terms, and how this informs their gender identities. My thesis further examines the intersections of masculinity and gender that are readily observable within MMA, and those that are less conspicuous or go largely unnoticed. Finally, my thesis explores how norms perpetuate gender stereotypes and highlight differences, as masculine norms persist in the fighting culture. The examination of gender norms in MMA contributes to a larger body of research concerning gender roles and norms in other social contexts. -

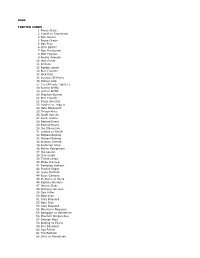

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

Jasmina and Frida

Lund University International Marketing and Brand Management Master Thesis June 2021 Distancing From Dirt A Qualitative Study on How Cancel Culture Has Become a Resource for Identity Construction in an Online Setting By: Jasmina Smajlovic & Frida Åhl Supervisor: Jon Bertilsson Examiner: Fleura Bardhi Abstract Title: Distancing From Dirt: A Qualitative Study on How Cancel Culture Has Become a Resource for Identity Construction in an Online Setting Course: BUSN39: Degree Project in Global Marketing Authors: Jasmina Smajlovic & Frida Åhl Supervisor: Jon Bertilsson Examiner: Fleura Bardhi Keywords: Identity Construction, Consumer Identity, Framing, Cancel Culture, Oatly, DisneyPlus Thesis Purpose: With this research we aim to understand the dynamics of consumers' use of cancel culture as a resource for their identity construction online. Theoretical Framework: Theories included were surrounding framing, morality, consumers as moral protagonists, purity and dirt as well as distaste and symbolic violence. These theories were selected to aid with the analysis of the empirical material and to add new insight to the concept of identity construction by negatively distancing from brands. Methodology: This study was conducted with a foundation of a relativist and social constructivist worldview. The research design used is qualitative and the netnography was conducted with an inductive approach. For the analysis, the method of content analysis was used to unfold underlying codes and patterns in the empirical material. Main Findings: This research found that consumers use cancel culture as a resource for identity construction in an online setting. By analysing the empirical material it was found that the constant use of viscous, satirical, emotional and political framing is a way for consumers to negatively distance themselves from brands and other consumers in order to build on their identities. -

Partisan Platforms: Responses to Perceived Liberal Bias in Social Media

Partisan Platforms: Responses to Perceived Liberal Bias in Social Media A Research Paper submitted to the Department of Engineering and Society Presented to the Faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia • Charlottesville, Virginia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Science, School of Engineering Luke Giraudeau Spring, 2021 On my honor as a University Student, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment as defined by the Honor Guidelines for Thesis-Related Assignments Signature __________________________________________ Date __________ Luke Giraudeau Approved __________________________________________ Date __________ Richard Jacques, Department of Engineering and Society Introduction In the United States, public opinion about tech companies’ political biases is divided along partisan lines (Vogels, Perrin, & Anderson, 2020). In the U.S. since 2018, 69 percent of Republicans claim that technology companies favor liberal views, whereas only 19 percent of Democrats say that technology companies favor the alternative view. Over 50 percent of liberals believe that perspectives are treated equally, whereas only 22 percent of conservatives feel this way. Critics who allege bias have organized to promote legislation such as the Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act (2020) as well as an executive order (Executive Order 13,925, 2020). Furthermore, conservative entrepreneurs have produced new social media platforms such as Gab and Parler that claim -

Un Iversida De Federa L Do P Ar an Á Set Or De Ciências

0 LEILA SALVINI A LUTA COMO “OFÍCIO DO CORPO”: ENTRE A DELIMITAÇÃO DO SUBCAMPO E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE UM HABITUS DO MIXED MARTIAL ARTS EM MULHERES LUTADORAS GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO FÍSICA GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO - SETOR DE CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS SETOR DE PÓS PROGRAMA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ FEDERAL UNIVERSIDADE CURITIBA 2017 1 LEILA SALVINI A LUTA COMO “OFÍCIO DO CORPO”: ENTRE A DELIMITAÇÃO DO SUBCAMPO E A CONSTITUIÇÃO DO HABITUS DO MIXED MARTIAL ARTS EM MULHERES LUTADORAS Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação (Doutorado) no Departamento de Educação Física, Setor de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Wanderley Marchi Júnior 2 3 4 À minha mãe e meu pai, por compartilharem comigo de um amor que educa e faz crescer. 5 AGRADECIMENTOS Se eu pude aprender algo ao longo desse percurso acadêmico é que nada é construído na solidão das leituras. O saber só toma forma, cor e sabor na prática do dia-a-dia, no ato de compartilhar as informações, as dúvidas, as descobertas, as alegrias, os sonhos, a cuia de chimarrão e o pôr do sol, o qual sinaliza que teremos uma noite de trabalho com a escrita da tese. Um trabalho acadêmico com esse perfil só foi possível porque tive ao meu lado pessoas que possibilitaram a sua materialização. É por isso que registro aqui a alegria e a gratidão de poder contar com vocês! Agradeço a Deus em seu inifito amor e bondade pela oportunidade de estar nesse tempo e espaço buscando a cada dia viver o amor em ação. Por proporcionar com sua luz infinita, perfeita e completa, tudo que é necessário para viver com plenitude.