Grappling with Gender and Hypermasculinity in Mixed Martial Arts Program Authorized to Offer Degree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brian Sandoval Governor STATE OF

Bruce Breslow Brian Sandoval STATE OF NEVADA Department Director Governor DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY ATHLETIC COMMISSION Bob Bennett Executive Director Chairman: Anthony A. Marnell III Members: Francisco V. Aguilar, Skip Avansino, Pat Lundvall, Michon Martin TO THE COMMISSION AND THE PUBLIC: AGENDA A duly authorized meeting of the Nevada State Athletic Commission will be held on Wednesday, February 17, 2016, at 9:00 a.m. at the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, 555 East Washington Avenue, Room 4500 Las Vegas, NV 89101. 1. Call to order. 2. Roll Call. 3. Public Comment. 4. Approval of the minutes of the meetings of December 17, 2015 and February 4, 2016 for possible action. 5. Adoption of the agenda for this meeting, for possible action. 6. Disclosures per NRS 281/281A. OLD BUSINESS: 1. Re‐hearing on appropriate discipline against mixed martial artist Wanderlei Silva, for possible action. CONSENT AGENDA: a. Date Requests 1. Request by Roy Englebrecht Promotions for the date of March 12, 2016 to promote a boxing event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on CBS Sports Network with a maximum of 7 fights and pending Executive Director Bob Bennett’s approval of the venue’s outdoor facilities, for possible action. 2. Request by World Series of Fighting for the date of April 2, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the Downtown Las Vegas Event Center in Las Vegas to be televised on NBC Sports Network, for possible action. 3. Request by Zuffa, LLC for the date of April 23, 2016 to promote a mixed martial arts event to be held at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas to be televised on PPV, for possible action. -

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Match Results

Match Results Date: 4/19/2014 Venue/Location: Amway Center -- Orlando, FL Promoter: UFC Commissioners Judge: Richard Bertrand Referee: John McCarthy Physician: Dr. Adam Brunson Commissioners Judge: Chris Lee Referee: Jorge Alonso Physician: Dr. George Panagakos Dr. Mark Williams, Chairman Judge: Jean Warring Referee: Jorge Ortiz Knockdown Timekeeper: Dr. Wayne Kearney Judge: Eliseo Rodriguez Referee: Herb Dean Alternate Referee Mr. Antonius DeSisto Judge: Hector Gomez Referee: Commissioners Present: Mr. Marco Lopez Judge: Tim Vannatta Referee: Mr. Tirso Martinez Judge: Derek Cleary Referee: Referee: Executive Director: Cynthia Hefren Asst. Executive Director: Frank Gentile Timekeeper(s): James Chittenden; Roy Silbert Event Type: MIXED MARTIAL ARTS Participants Federal ID Hometown Weight DOB Sch Rds Results Officials Suspensions and Remarks Claim form, knee, indefinite susp, neruo Referee: John McCarthy; Jack May 110-622 Costa Mesa, CA 252.5 lbs 4/14/1981 clearance 3 Judges: Jean Warring; Chris 1 Winner TKO 4:23 1st Lee; Richard Bertrand Referee stoppage from strikes Derrick Lewis 116-645 Houston, TX 256.0 lbs 2/7/1985 Rd Referee: Jorge Ortiz; Judges: Chas Skelly 101-842 Keller, TX 145.0 lbs 5/11/1985 2 3 Eliseo Rodriguez; Tim Winner by Majority Vannatta; Richard Green Suspension 180 days or Facial CT Marsid Bektic 105-060 Coconut Creek, FL 146.0 lbs 2/11/1991 Decision clearance Referee: Jorge Alonso; Ray Borg 127-020 Albuquerqu, NM 125.5 lbs 8/4/1993 3 3 Judges: Chris Lee; Hector Winner by Split Gomez; Derek Cleary Dustin Ortiz 121-691 -

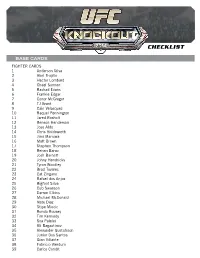

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

LGBT Identity and Crime

LGBT Identity and Crime LGBT Identity and Crime* JORDAN BLAIR WOODS** Abstract Recent studies report that LGBT adults and youth dispropor- tionately face hardships that are risk factors for criminal offending and victimization. Some of these factors include higher rates of poverty, over- representation in the youth homeless population, and overrepresentation in the foster care system. Despite these risk factors, there is a lack of study and available data on LGBT people who come into contact with the crim- inal justice system as offenders or as victims. Through an original intellectual history of the treatment of LGBT identity and crime, this Article provides insight into how this problem in LGBT criminal justice developed and examines directions to move beyond it. The history shows that until the mid-1970s, the criminalization of homosexuality left little room to think of LGBT people in the criminal justice system as anything other than deviant sexual offenders. The trend to decriminalize sodomy in the mid-1970s opened a narrow space for schol- ars, advocates, and policymakers to use antidiscrimination principles to redefine LGBT people in the criminal justice system as innocent and non- deviant hate crime victims, as opposed to deviant sexual offenders. Although this paradigm shift has contributed to some important gains for LGBT people, this Article argues that it cannot be celebrated as * Originally published in the California Law Review. ** Assistant Professor of Law, University of Arkansas School of Law, Fayetteville. I am thankful for the helpful suggestions from Samuel Bray, Devon Carbado, Maureen Carroll, Steve Clowney, Beth Colgan, Sharon Dolovich, Will Foster, Brian R. -

Undefeated Olympians Collide As Champion Ronda Rousey Meets Sara Mcmann at Ufc® 170 Saturday, February 22

UNDEFEATED OLYMPIANS COLLIDE AS CHAMPION RONDA ROUSEY MEETS SARA MCMANN AT UFC® 170 SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 22 Las Vegas, Nevada – In what could prove to be her toughest challenge yet, UFC® women’s bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey (8-0, fighting out of Venice, Calif.) squares off against undefeated wrestling sensation Sara McMann (7-0, fighting out of Gaffney, SC) in a battle of Olympic medalists at UFC® 170 at the Mandalay Bay Events Center Saturday, Feb. 22. A bronze medal winner in Judo at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, Rousey recently defeated her bitter rival Miesha Tate at UFC 168 to retain the women’s bantamweight belt and remain the divison’s only champion. Now she takes on McMann, who comes in as the most decorated wrestler in the weight class, having also earned Olympic silver at the 2004 games in Athens in free- style wrestling. In addition to the Rousey-McMann tilt, (No. 3) Rashad Evans (19-3, fighting out of Boca Raton, Fla.), a former light heavyweight champion, battles the Strikeforce Heavyweight Grand Prix winner Daniel Cormier (13-0, fighting out of San Jose, Calif.) in his debut at the 205-pound weight class. Evans comes into the bout sporting consecutive wins over Dan Henderson and Chael Sonnen while Cormier is looking to keep his unblemished professional record and make a statement in his new division. The card also features Brazilian jiu-jitsu ace (No. 6) Demian Maia (18-5, fighting out of Sao Paulo, Brazil) matching up against Canadian prodigy and Georges-St. Pierre training partner (no. 4) Rory MacDonald (15-2, fighting out of Montreal, Canada) in a battle of Top 10-ranked welterweights. -

Toxic Masculinity Involves the Need to Aggressively Compete and Dominate Others and Encompasses the Most Problematic Proclivities in Men

Toxic Masculinity as a Barrier to Mental Health Treatment in Prison � Terry A. Kupers The Wright Institute The current article addresses gender issues that become magnified in prison settings and contribute to heightened resistance in psychotherapy and other forms of mental health treatment. Toxic masculinity involves the need to aggressively compete and dominate others and encompasses the most problematic proclivities in men. These same male proclivities foster resistance to psychotherapy. Some of the stresses and complexities of life in men’s prisons are explored. The relation between hegemonic masculin- ity and toxic masculinity is examined. The discussion proceeds to the interplay between individual male characteristics and institutional dynam- ics that intensify toxic masculinity. A discussion of some structural obsta- cles to mental health treatment in prison and resistances on the part of prisoners is followed by some general recommendations for the therapist in this context. © 2005 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. J Clin Psychol 61: 713– 724, 2005. Keywords: masculinities; prison; toxic masculinity; gender; prison mental health Over 2 million persons are in jail and prison in the United States, and over 90% of prisoners are male (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2004). Most prisoners come from low income backgrounds, and a dispropor tionate number are persons of color (Mauer, 1999). Contrary to popular stereotypes, 75% of men entering prison have not been convicted of a violent crime, and a disproportionate number have been convicted of drug-related crimes. Many of them urgently need mental health services because they suffer from serious mental illness, or they require treatment for substance abuse, dysfunctional anger, or proclivity toward sex offenses or domestic violence (Human Rights Watch, 2003; Lamb & Weinberger, 1998; Breiman & Bonner, 2001). -

Female Fighters Join EA SPORTS UFC Roster; Mark First Ever Appearance in a UFC Video Game

September 4, 2013 Female Fighters Join EA SPORTS UFC Roster; Mark First Ever Appearance in a UFC Video Game The Ultimate Fighter Coaches Ronda Rousey and Miesha Tate First Female Fighters Revealed REDWOOD CITY, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: EA) today announced that EA SPORTS™ UFC will feature playable female fighters for the first time ever in a UFC videogame. This groundbreaking moment is headlined by UFC Women's Bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey and top bantamweight contender Miesha Tate, the historic inaugural female coaches on the upcoming season of The Ultimate Fighter. Starting next Spring, players will "Feel the Fight" in the Octagon™ and experience the crippling power of Rousey's signature armbar, the ferocious intensity of Tate's grappling, and many other fighting styles from an esteemed roster of female fighters in EA SPORTS UFC. "This is a great moment for videogames and for Mixed Martial Arts," said Dean Richards, General Manager, EA SPORTS UFC. "In our commitment to delivering the most realistic fighting experience ever achieved, we wanted to represent the full spectrum of talent and diversity of all the fighters in the sport, including women who have become an undeniable force to be reckoned with." "Since we added the Women's Bantamweight division earlier this year, the women have impressed everyone," said Dana White, UFC President. "The fights are always exciting, Ronda Rousey is as talented as any champion in the UFC and her rivalry with Miesha Tate is one of the most intense in UFC history. The female division has become a huge part of the UFC and fans will now be able to experience fighting with them in the game." Watch Ronda Rousey talk to EA SPORTS about her upcoming bout with Miesha Tate Powered by EA SPORTS IGNITE technology, EA SPORTS UFC brings the action, emotion and intensity inside the Octagon to life in ways that were never before possible. -

What Motivates Heterosexuals to Be Prejudiced Towards Gay Men And

Understanding Prejudice and Discrimination: Heterosexuals’ Motivations for Engaging in Homonegativity Directed Toward Gay Men A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Department of Psychology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Lisa M. Jewell © Lisa M. Jewell, September 2007. All rights reserved. Understanding Prejudice PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work or, in her absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Psychology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Understanding Prejudice ABSTRACT To date, little research has documented the prevalence of anti-gay behaviours on Canadian university campuses or directly explored heterosexual men’s and women’s self-reported reasons for holding negative attitudes toward gay men and engaging in anti-gay behaviours. -

Incidents of Misogyny and Sexism in the UFC Rampage Jackson • in The

Incidents of Misogyny and Sexism in the UFC Rampage Jackson In the YouTube video, called “How To Pick Up a Gurl – Fast,” Rampage Jackson attempts to rape a woman in a parking garage. Before attacking his target, Rampage instructs viewers to use chloroform as “something to help her relax” and zip ties. The UFC fighter explains, “I like this parking lot because my cousin work for the security company so I know the cameras are gonna be out of service right now.”1 As Rampage stalks his victim, he comments, “And I hope she got low self-esteem.” The video has received over 200,000 views and remains accessible for public viewing.2 To our knowledge, the UFC has not issued an official statement, fined, or suspended Jackson for the video. In July 2008, video footage was uploaded of Rampage positioning himself behind a female Japanese reporter, placing his hand on her thigh, and dry humping her. When she moves away from him, he follows her and grabs her leg.3 The video currently has 1.4 million views. In June 2009, Rampage, in the middle of an interview, holds Cage Potato reporter Heather Nichols against him, and dry humps her for a full 37 seconds. He continues to hold her after she attempts to end the interview, and does not let her go until a man walks up to Rampage and taps him on the shoulder a few seconds after the interview ends. The video has over 9.8 million views.4 In late May 2011, when being interviewed by MMA Heat host Karyn Bryant, Rampage replied that she’s “Jamaican me horny” in response to her statement that she was Jamaican, black and white. -

Hegemonic Masculine Conceptualisation in Gang Culture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Greenwich Academic Literature Archive Hegemonic masculine conceptualisation in gang culture Russell Luyt and Don Foster* Department of Psychology, University of Cape Town, Private Bag, Rondebosch, 7701 This research sought to investigate the relationship between gang processes and differing forms of masculine expression. Three hundred and sixteen male participants, drawn from secondary schools within Cape Town, were included in the study. These schools were in areas differentially characterised by gang activity. The questionnaire included the newly devised Male Attitude Norm Inventory designed to explore hegemonic conceptualisations of masculinity. Factor analytic procedures rendered a three-factor model stressing the importance of male toughness, success and control. Through a series of t-tests for independent samples, as well as supporting qualitative data, participants from areas characterised by high gang activity were found to support these hegemonic elements to a significantly greater extent. *To whom correspondence should be addressed “Die gangsters van vandag is almal jonk en hulle sterf Decker and van Winkle (1996) stress that the study of gangs is ook jonk. Een van my beste vriende was ‘n not a new phenomenon, having taken place for over a century, ‘Ghetto Kid’ toe het ek nie meer met hom gepraat and note their prevalence in contexts defined by rapid nie. Saterdag skiet ander gangsters hom dood. En hy population growth and economic deprivation. In South Africa was net 18 jaar oud” their activity is said to have intensified largely in response to the (Participant 188: Area B). -

The Reproduction of Hypermasculinity, Misogyny and Rape Culture in Online Video Game Interactions

THE REPRODUCTION OF HYPERMASCULINITY, MISOGYNY AND RAPE CULTURE IN ONLINE VIDEO GAME INTERACTIONS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Katherine Mary Bullock In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Program: Sociology July 2017 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title THE REPRODUCTION OF HYPERMASCULINITY, MISOGYNY AND RAPE CULTURE IN ONLINE VIDEO GAME INTERACTIONS By Katherine Mary Bullock The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Christina Weber Chair Christopher Whitsel Robert Mejia Approved: July 31, 2017 Jeffery Bumgarner Date Department Chair ABSTRACT Playing video games is a popular past time for many, and the introduction of online gaming allows people of various backgrounds to interact with one another. Yet, it is clear in the wake of incidences such as Gamergate which saw threats directed towards women, that gaming is still considered a male space that is hostile towards women. Through content analysis of online spaces, this research sought to understand how violence towards femininity manifests in gaming. Through Louis Althusser’s (1972) concept of Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs) I explore how hypermasculine and misogynistic ideologies are reproduced in online gaming culture. It was found that violence towards women, hypermasculinity, and misogyny were perpetuated through the expression of dominant ideologies that place men above women. That being said, there were a significant number of people who spoke out against these ideologies thus working to dismantle the dominant attitudes that contribute to violence towards women. -

The Impact of Hypermasculinity on Students' Development in Fraternity

University of San Diego Digital USD M.A. in Higher Education Leadership: Action School of Leadership and Education Sciences Research Projects Spring 5-13-2019 The mpI act of Hypermasculinity on Students' Development in Fraternity Organizations Cristian McGough University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/soles-mahel-action Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Leadership Studies Commons Digital USD Citation McGough, Cristian, "The mpI act of Hypermasculinity on Students' Development in Fraternity Organizations" (2019). M.A. in Higher Education Leadership: Action Research Projects. 26. https://digital.sandiego.edu/soles-mahel-action/26 This Action research project: Open access is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Leadership and Education Sciences at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in M.A. in Higher Education Leadership: Action Research Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: THE IMPACT OF HYPERMASCULINITY 1 The Impact of Hypermasculinity on Students’ Development in Fraternity Organizations Cristian McGough University of San Diego THE IMPACT OF HYPERMASCULINITY 2 Abstract The purpose of my study was to explore the concept of hypermasculinity in fraternal organizations and how that may affect students’ personal development during their collegiate years. My research question was, how can I work with fraternity students to understand what contributes to hypermasculinity and provide support that will better promote an inclusive masculine culture? My findings indicate that certain environments in fraternity organizations promote hypermasculinity traits and that students on the executive board of the Interfraternity Council are seeking spaces to have dialogue about their experiences to challenge the norms of fraternity organizations.