Forms of Community Service: Guy Butler's Literary Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Professor Catriona Macleod

RRR | Cover 2015 v2 11/9/16 10:17 AM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composite RRR 2015 | Features 11/12/16 1:36 PM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K RHODES UNIVERSITY RESEARCH REPORT A publication of the Rhodes University Research Office, compiled and edited by Tarryn Gillitt, Busi Goba, Patricia Jacob, Jill Macgregor and Jaine Roberts Design & Layout: Sally Dore Research Office Director: Jaine Roberts [email protected] Tel: +27 (46) 603 8756/7572 www.ru.ac.za Cover: Rhodes University researchers Pam Maseko, Nomalanga Mkhize, Heila Lotz-Sisitka, Ruth Simbao, Anthea Garman and Catriona Macleod Cover Photos: Paul Greenway/www.3pphotography.com RESEARCH REPORT 2015 Composite RRR 2015 | Features 11/12/16 1:36 PM Page 2 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K CONTENTS 01 FOREWORD Dr Sizwe Mabizela, Vice-Chancellor 03 INTRODUCTION Dr Peter Clayton, Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Research & Development 05 TOP 30 RESEARCHERS 06 PHD GRADUATES 11 VICE-CHANCELLOR’S BOOK AWARD Professor Anthea Garman 13 VICE-CHANCELLOR’S DISTINGUISHED SENIOR RESEARCH AWARD Professor Catriona Macleod 15 VICE-CHANCELLOR’S DISTINGUISHED RESEARCH AWARD Dr Adrienne Edkins 17 SARChI CHAIRS Professor Heila Lotz-Sisitka, Professor Ruth Simbao and Dr Adrienne Edkins 23 AFRICAN LANGUAGES, SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE Associate Professor Pamela Maseko 25 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dr Nomalanga Mkhize RESEARCH REPORT 2015 Composite RRR 2015 | Features 11/12/16 1:34 PM Page 3 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K RHODES RESEARCH 2015 RESEARCH REPORT DEPARTMENT PUBLICATIONS AFFILIATES, INSTITUTES AND 28 Publications from the Vice-Chancellorate -

Ernestine White-Mifetu

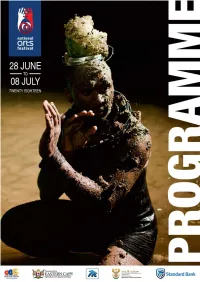

20 2018 Festival Curators Visual and Performance Art Ernestine White-Mifetu ERNESTINE WHITE-MIFETU is currently the curator of Contemporary Art at Iziko’s South African National Gallery. Her experience within the arts and culture sector spans a period of fifteen years. She holds a Bachelors degree in Fine Art (1999) cum CURATED PROGRAMME laude from the State University of Purchase College in New York, a Master Printer degree in Fine Art Lithography (2001) from the Tamarind Institute in New Mexico, a Masters degree in Fine Art (2004) from the Michaelis School of Fine Art, Cape Town, and a Honours degree in Curatorship (2013) from the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art. Ms White-Mifetu obtained her initial curatorial experience working as the Exhibitions Coordinator (2004-2006) and thereafter as Senior Projects Coordinator for Parliament’s nation building initiative, the Parliamentary Millennium Programme. Prior to this she worked as the Collections Manager for Iziko’s South African National Gallery. As an independent artist her work can be found in major collections in South Africa as well as in the United States. Ernestine White’s most recent accomplishment was the inclusion of her artwork into permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, US. Music Samson Diamond SAMSON DIAMOND is the appointed leader of the Odeion String Quartet at the University of the Free State and concertmaster of the Free State Symphony Orchestra (FSSO). He has appeared as violin soloist with all premier South African orchestras and has played principal second of Europe’s first black and ethnic minority orchestra, Chineke! Orchestra, since its inception. -

Studying Literacy As Situated Social Practice

Studying Literacy as Situated Social Practice: The Application and Development of a Research Orientation for Purposes of Addressing Educational and Social Issues in South African Contexts Mastin Prinsloo Town Thesis presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Cape of Department of Social Anthropology Graduate School in Humanities UnivesityUNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN Supervisor Associate Professor Andrew Spiegel September 2005 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work, except where indicated, and has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at any other university. Signed: signature removed Mastin Prinsloo September 2005 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my mother Isabelle, and to my son Ben. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Associate Professor Andrew Spiegel wholeheartedly for his support and commitment from the inception to the completion of this research. IV Abstract This is a study of the application in South Africa of a social practices approach to the study of literacy. A social practices approach conceptualizes literacy practices as variable practices which link people, linguistic resources, media objects, and strategies for meaning-making in contextualized ways. These literacy practices are seen as varying across broad social contexts, and across social domains within these contexts, and they can be studied ethnographically. -

European Technology on the Great Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 2008 Technological Introductions and Social Change: European Technology on the Great Plains Andrew LaBounty Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons LaBounty, Andrew, "Technological Introductions and Social Change: European Technology on the Great Plains" (2008). Nebraska Anthropologist. 39. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/39 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Technological Introductions and Social Change: European Technology on the Great Plains Andrew LaBounty Abstract: This paper will explore the changing structure of American Indian society with the introduction of Euro-American technology and practices on the Plains. I intend to compare and contrast social aspects of Indian culture before and after contact, including the presence and intensity of marriage exchanges, levels of exogamy, the intensity ofpolygyny, and degree ofstratification among native groups. These comparisons will shed light on the mechanisms of culture change, showing the entire process to be gradual and often due to conscious, immediately beneficial decisions. Introduction Technological introductions and innovations are a key aspect of cultural change, as technology tends to evolve according to cultural needs. In some cases however, technology has also been a primary cause of culture change. This has been especially evident in the Great Plains among the American Indians in the 17th and 18th centuries, as European explorers and traders introduced new technologies. -

Second Show Announced – Thursday October 25Th >>> New Tickets Onsale Thursday 27 September 9Am > Ticketmaster Details Below

Solid Entertainment, ZM and Groove Guide proudly present……. >>>SECOND SHOW ANNOUNCED – THURSDAY OCTOBER 25TH >>> NEW TICKETS ONSALE THURSDAY 27 SEPTEMBER 9AM > TICKETMASTER DETAILS BELOW Original press release follows: Solid Entertainment are delighted to announce that ELLIE GOULDING will be playing her first ever show in New Zealand at The Studio in Auckland on Friday October 26th. Ellie arrives with perfect timing – a highly anticipated brand new second album Halcyon, an artist capturing hearts and imaginations everywhere she plays, and embarking on a year set to take her stratospheric! Ellie Goulding’s astounding voice has always been a universally acclaimed centrepiece. Her live shows ricochet from electropop dynamite immersed in dance beats from dubstep to electronica all the way through to sparse ‘folktronica’, where her multi-textured voice marks Ellie as one of this generations’s most enthralling, singular and compelling songwriters. UK based Ellie Goulding first rose to prominence in 2010 when she topped the BBC Sound of 2010 poll and won the Brit Awards Critics Choice Award, becoming only the second artist (after Adele in 2008) to scoop both these awards in the same year. Goulding’s debut album Lights went straight to Number 1 in the UK and garnered the hit singles Starry Eyed, Under The Sheets, and Guns and Horses. Since the albums release in 2010 it has slowly but surely spread it’s magic around the world. The album’s title track Lights was released in the US in March 2011 and in recent weeks has completed a staggering record-breaking climb. Now , 18 months later, and during its thirty third week on the chart, the song reached a peak position of Number 2 in the Billboard Hot 100, whilst the album has gone double-platinum. -

Buffalo Bill's Wild West 5Bow

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection isrorical Sketches Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection #7-S / <W/'"/ft / • y/1 Far-simile of Col. 'Wr. F. CODY'S Commiasion an Brigadier-General in the NATIONAL, GUARD (OF THE STATE OF NEBRASKA). Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection SMOKE g 11111111111111111f• 1111 1111 111111• 11111• • r11111iii • iii111• • 11 ii• 111• 111 11 > unit AAYO'S TOBACCO. FACTORY: RICHMOND, VIRGINIA. IT Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection If Something is wanted, Buy ... THE "TRUMP" WATCH. Price, LET US HAVE THE NAME OF ANY JEWELER WHO DOES NOT KEEP OUR WATCHES. Don't get fooled with a Clock Watch— After we stopped making the long-wind watch, the market became flooded with the cheap Swiss and poor clock watches.; so we made this new American Duplex quick-wind movement, which we warrant to be a perfect time-keeper. If Something RICH is wanted== yet at low purchase price—send tor one of our higher grade, in gold-filled or sterling silver case. The Elfin for Ladies. The smallest watch made in this country. The v^y for Boys. Just the right size for a Boy'« pocket. The 1 UAWUU for Gentlemen. Very thin and graceful in shape. ALL HAVE OUK UNQUESTIONED GUARANTEE WITH FIFTEEN-YEAR WARRANT ON CASES. Our Watches should be for sale by all Jewelers. If you are not within a convenient distance of a dealer, or for any reason have difficulty in getting what you want, write to us and we will help you. -

An Analysis of Superhero Genre in Captain America the Winter Soldier Film

AN ANALYSIS OF SUPERHERO GENRE IN CAPTAIN AMERICA THE WINTER SOLDIER FILM A Thesis Submitted to Adab and Humanities Faculty In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Strata One NURAINI RISMAWATI 1110026000065 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2015 ABSTRACT Nuraini Rismawati, An Analysis of Superhero Genre in Captain America The Winter Soldier Film. A Thesis: English Letters Department, Adab and Humanities Faculty, State Islamic University of Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, 2015. Captain America The Winter Soldier (2014) film directed by Anthony Russo and Joe Russo is the unit analysis of this research. The writer uses this film to reveal it as the superhero genre. The purpose of this research is to know how superhero genre stands as the specific genre through six elements, which are setting, iconography, location, narratives events, characters, and plot structure by Jane Stokes and concepts of superhero genre by Peter Coogan. The writer uses qualitative descriptive analysis method to analyze it. The data are collected from the film that analyzed by structuralism approach. The Result of this research shows that Superhero genre can be a specific genre and stand as its own genre. The writer finds that many of reviews are not mention this film as superhero genre. The writer makes it clear and invite for every critics or researchers to tell superhero genre as the main genre without mention others genre in the reviews of any superhero film. Keywords: Captain America The Winter Soldier, Genre, Superhero film. i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due knowledge has been made in the text. -

The West Point Class of 1861 and the First Manassas Campaign

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 5-8-2020 Faithful Unto Death: The West Point Class of 1861 and the First Manassas Campaign Jessie Fitzgerald Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Jessie, "Faithful Unto Death: The West Point Class of 1861 and the First Manassas Campaign" (2020). Student Research Submissions. 322. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/322 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faithful Unto Death: The West Point Class of 1861 and the First Manassas Campaign Jessie Fitzgerald History 485: Historical Research Dr. Porter Blakemore April 24, 2020 The West Point Class of 1861 graduated on the eve of the American Civil War as a class defined by regional and political lines. As the secession crisis heated up, cadets appointed from southern states resigned and went south, some just two weeks shy of graduating, while northern cadets remained at West Point. Two months after graduation, the class exhibited their military ability and the value of their training during the Manassas Campaign in July of 1861. They also demonstrated a commitment of duty to the causes and countries they fought for. Furthermore, they showed devotion to each other, even as they fought on opposite sides of the war. The Civil War careers of six exemplary members of the class demonstrated the influence and significance of West Point to the war. -

Guns and Horses, C 1750 to C 1850: Korana – People Or Raiding Hordes? 11

Guns and Horses, c 1750 to c 1850: Korana – People or Raiding Hordes? 11 Guns and Horses, c 1750 to c 1850: Korana – People or Raiding Hordes? MICHAŁ LEŚNIEWSKI University of Warsaw, Poland Uniwersytet Warszawski, Wydział Historii Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28 00-927 Warszawa, Poland [email protected] Abstract. The aim of the present article is to discuss the question of identity of the Ko- rana, one of many groups of mixed African/European culture which roamed South African Highveld during the first half of the 19th century. Among the scholars there is growing interest in frontier communities, such as Bastaards, Griquas and other Oorlam groups and the role they played in South African history and politics during the first decades of the 19th century. One of those communities were the Korana. But one of the problems the con- temporary scholars have is the diversity of those communities. There were several preda- tory groups which roamed the Highveld: Oorlams, Bastaards, Griqua, Hartenaars, Korana and Bergenaars. They were very similar in their pedigree and shared many elements of material culture. Therefore specialists tend to define Korana by their lifestyle. But obviously such a definition is very wide, and in fact too inclusive. In this article author tries to point to other options, of creating more exact definition, of this community. Keywords: African studies; colonial studies; South Africa; 18th and 19th century; migrations; Oorlam communities; Korana; ethnic composition and identity; cultural influences The first half of the 19th century was a time of upheaval in South Africa, even if we accept the point of view of some contemporary historians that the difaqane/ mfecane and the Great Trek were just historiographical inventions (Cobbing 1988; Wright 1989; Etherington 2001: 329-346). -

Redskin and Cowboy a Tale of the Western Plains

REDSKIN AND COWBOY A TALE OF THE WESTERN PLAINS BY G. A. HENTY 2 PREFACE My dear Lads, There are but few words of preface needed to a story that is not historical. The principal part of the tale is laid among the cowboys of the Western States of America, a body of men unrivalled in point of hardihood and devotion to work, as well as in reckless courage and wild daring. Texas, which twenty-five years ago was the great ranching state, is no longer the home of the typical cowboy, but he still exists and flourishes in New Mexico and the northern States and Territories. The picture I have given of their life can be relied upon, and its adventures and dangers are in no degree coloured, as I have taken them from the lips of a near relative of my own who was for some years working as a cowboy in New Mexico. He was an actor in many of the scenes described, and so far from my having heightened or embellished them, I may say that I have given but a small proportion of the perilous adventures through which he went, for had I given them in full it would, I am sure, have seemed to you that the story was too improbable to be true. In treating of cowboy life, indeed, it may well be said that truth is stranger than fiction. Yours sincerely, G. A. HENTY ©Ichthus Academy Redskin and Cowboy 3 CONTENTS I. An Advertisement …………………………………………………………….... 4 II. Terrible News …………………………………………………………………. 16 III. The Wanderer's Return ……………………………………………………... -

Lay of the Land

Lay of the Land The 1862 Dakota War, A Play with Choruses J.R. Weber 2017 Cover photo: Wowinape, Taoyateduta’s son, in 1864. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.” Copyright © Jim Weber, 2017 ISBN: 978-0-9894303-8-8 Book and cover design by Adrianna Sutton www.adriannasutton.com And what the dead had no speech for when living, They can tell you, being dead: The communication Of the dead is tongued with fre beyond the language of the living. — T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets, “Little Gidding” Introduction On August 18, 1862, at seven o’clock in the morning, Mdewakanton Sioux warriors fled quietly onto the Lower Sioux Agency in Minnesota and launched an unexpected attack, frst on the government-licensed merchants who sold them supplies, including food, and then on the support facilities of the Agency — the doctor’s quarters, the ferry over the Minnesota River, the barns housing horses and livestock. In a fash of powder, dozens of white and mixed-blood men, women, and children were killed. Later that day and in ensuing days, warriors swept through the surrounding communities and deep into central Minnesota, killing farmers and their families and besieging towns. The toll on white Minnesotans reached hundreds and among the Mdewakantons dozens dead. Tensions had been high before the attacks, fueled by aggressive settlement-and-removal initiatives, realized via treaties and extra-legal settlements around the Minnesota River valley, from St. Paul in the east to the Red River valley at the border of the Dakota Territory and north into central Minnesota. Although the Mdewakanton Sioux had agreed to sales of their land in exchange for annuities from the U.S.