Native Americans: Native Changing Landscape a Unit 8 Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing of Menthol Cigarettes and Consumer Perceptions Joshua Rising1*, Lori Alexander2

Rising and Alexander Tobacco Induced Diseases 2011, 9(Suppl 1):S2 http://www.tobaccoinduceddiseases.com/content/9/S1/S2 REVIEW Open Access Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions Joshua Rising1*, Lori Alexander2 Abstract In order to more fully understand why individuals smoke menthol cigarettes, it is important to understand the perceptions held by youth and adults regarding menthol cigarettes. Perceptions are driven by many factors, and one factor that can be important is marketing. This review seeks to examine what role, if any, the marketing of menthol cigarettes plays in the formation of consumer perceptions of menthol cigarettes. The available literature suggests that menthol cigarettes may be perceived as safer choices than non-menthol cigarettes. Furthermore, there is significant overlap between menthol cigarette advertising campaigns and the perceptions of these products held by consumers. The marketing of menthol cigarettes has been higher in publications and venues whose target audiences are Blacks/African Americans. Finally, there appears to have been changes in cigarette menthol content over the past decade, which has been viewed by some researchers as an effort to attract different types of smokers. Review Summarized in this review are 35 articles found to The marketing of cigarettes is a significant expenditure have either direct relevance to these questions, or were for the tobacco industry; in 2006, the tobacco industry used to provide relevant background information. Many spent a total of $12.49 billion on advertising and promo- ofthesearticleswereidentifiedthroughareviewofthe tion of cigarettes including menthol brands, which literature conducted by the National Cancer Institute in represent 20% of the market share [1]. -

Plains Indians

Your Name Keyboarding II xx Period Mr. Behling Current Date Plains Indians The American Plains Indians are among the best known of all Native Americans. These Indians played a significant role in shaping the history of the West. Some of the more noteworthy Plains Indians were Big Foot, Black Kettle, Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Spotted Tail. Big Foot Big Foot (?1825-1890) was also known as Spotted Elk. Born in the northern Great Plains, he eventually became a Minneconjou Teton Sioux chief. He was part of a tribal delegation that traveled to Washington, D. C., and worked to establish schools throughout the Sioux Territory. He was one of those massacred at Wounded Knee in December 1890 (Bowman, 1995, 63). Black Kettle Black Kettle (?1803-1868) was born near the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota. He was recognized as a Southern Cheyenne peace chief for his efforts to bring peace to the region. However, his attempts at accommodation were not successful, and his band was massacred at Sand Creek in 1864. Even though he continued to seek peace, he was killed with the remainder of his tribe in the Washita Valley of Oklahoma in 1868 (Bowman, 1995, 67). Crazy Horse Crazy Horse (?1842-1877) was also born near the Black Hills. His father was a medicine man; his mother was the sister of Spotted Tail. He was recognized as a skilled hunter and fighter. Crazy Horse believed he was immune from battle injury and took part in all the major Sioux battles to protect the Black Hills against white intrusion. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

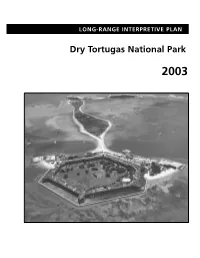

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Dry Tortugas National Park

LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Cover Photograph: Aerial view of Fort Jefferson on Garden Key (fore- ground) and Bush Key (background). COMPREHENSIVE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Prepared by: Department of Interpretive Planning Harpers Ferry Design Center and the Interpretive Staff of Dry Tortugas National Park and Everglades National Park INTRODUCTION About 70 miles west of Key West, Florida, lies a string of seven islands called the Dry Tortugas. These sand and coral reef islands, or keys, along with 100 square miles of shallow waters and shoals that surround them, make up Dry Tortugas National Park. Here, clear views of water and sky extend to the horizon, broken only by an occasional island. Below and above the horizon line are natural and historical treasures that continue to beckon and amaze those visitors who venture here. Warm, clear, shallow, and well-lit waters around these tropical islands provide ideal conditions for coral reefs. Tiny, primitive animals called polyps live in colonies under these waters and form skeletons from cal- cium carbonate which, over centuries, create coral reefs. These reef ecosystems support a wealth of marine life such as sea anemones, sea fans, lobsters, and many other animal and plant species. Throughout these fragile habitats, colorful fishes swim, feed, court, and thrive. Sea turtles−−once so numerous they inspired Spanish explorer Ponce de León to name these islands “Las Tortugas” in 1513−−still live in these waters. Loggerhead and Green sea turtles crawl onto sand beaches here to lay hundreds of eggs. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

Native American Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Ethnozoology Herman A

IK: Other Ways of Knowing A publication of The Interinstitutional Center for Indigenous Knowledge at The Pennsylvania State University Libraries Editors: Audrey Maretzki Amy Paster Helen Sheehy Managing Editor: Mark Mattson Associate Editor: Abigail Houston Assistant Editors: Teodora Hasegan Rachel Nill Section Editor: Nonny Schlotzhauer A publication of Penn State Library’s Open Publishing Cover photo taken by Nick Vanoster ISSN: 2377-3413 doi:10.18113/P8ik360314 IK: Other Ways of Knowing Table of Contents CONTENTS FRONT MATTER From the Editors………………………………………………………………………………………...i-ii PEER REVIEWED Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western Science for Optimal Natural Resource Management Serra Jeanette Hoagland……………………………………………………………………………….1-15 Strokes Unfolding Unexplored World: Drawing as an Instrument to Know the World of Aadivasi Children in India Rajashri Ashok Tikhe………………………………………………………………………………...16-29 Dancing Together: The Lakota Sun Dance and Ethical Intercultural Exchange Ronan Hallowell……………………………………………………………………………………...30-52 BOARD REVIEWED Field Report: Collecting Data on the Influence of Culture and Indigenous Knowledge on Breast Cancer Among Women in Nigeria Bilikisu Elewonibi and Rhonda BeLue………………………………………………………………53-59 Prioritizing Women’s Knowledge in Climate Change: Preparing for My Dissertation Research in Indonesia Sarah Eissler………………………………………………………………………………………….60-66 The Library for Food Sovereignty: A Field Report Freya Yost…………………………………………………………………………………………….67-73 REVIEWS AND RESOURCES A Review of -

Traditional Knowledge of Fire Use by the Confederated Tribes of Warm T Springs in the Eastside Cascades of Oregon ⁎ Michelle M

Forest Ecology and Management 450 (2019) 117405 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Traditional knowledge of fire use by the Confederated Tribes of Warm T Springs in the eastside Cascades of Oregon ⁎ Michelle M. Steen-Adamsa, , Susan Charnleya, Rebecca J. McLainb, Mark D.O. Adamsa, Kendra L. Wendela a USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 620 SW Main St., Suite 502, Portland, OR 97205, UnitedStates b Portland State University, Institute for Sustainable Solutions, 1600 SW 4th Avenue, Suite 110, Portland, OR 97201, United States ABSTRACT We examined traditional knowledge of fire use by the Ichishikin (Sahaptin), Kitsht Wasco (Wasco), and Numu (Northern Paiute) peoples (now Confederated Tribesof Warm Springs, CTWS) in the eastside Cascades of Oregon to generate insights for restoring conifer forest landscapes and enhancing culturally-valued resources. We examined qualitative and geospatial data derived from oral history interviews, participatory GIS focus groups, archival records, and historical forest surveys to characterize cultural fire regimes (CFRs) –an element of historical fire regimes– of moist mixed conifer (MMC), dry mixed conifer (DMC), and shrub-grassland (SG) zones. Our ethnohistorical evidence indicated a pronounced cultural fire regime in the MMC zone, but not in the two drier zones. The CFR of the MMCzonewas characterized by frequent (few-year recurrence), low-severity burns distributed in a shifting pattern. This regime helped to maintain forest openings created by previous ignitions, resulting from lightning or possibly human-set, that had burned large areas. The CFR was influenced by the CTWS traditional knowledge system, which consisted of four elements: fire use and associated resource tending practices, tribal ecological principles, the seasonal round (the migratory pattern tofulfill resource needs), and culture. -

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Mountain-Prairie Region 6 Overview of the Service’S Mountain-Prairie Region

U.S. U.S.Fish Fish & Wildlife & Wildlife Service Service Mountain-Prairie Region 6 Overview of the Service’s Mountain-Prairie Region Widgeon Pond at Red Rocks Lake National Wildlife Refuge / USFWS The Mountain-Prairie Region consists of federal agencies such as the Department Regional Demographics 8 states in the heart of the American of Defense. Energy development, ■ Land area: 737,884 square miles west including Colorado, Kansas, agricultural trends and urbanization all (468,573,000 acres) Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, exert influences on the Region’s ■ Population: 15,403,172 (Roughly 2.5 to South Dakota, Utah and Wyoming. The landscapes. 1 urban to rural ratio) region is defined by three distinct ■ Members of Congress: 37 landscapes. In the east lie the central Resource Facts and Figures ■ Federally Recognized Indian Tribes: 40 and northern Great Plains, primarily the ■ Approximately 5,751,358 acres ■ Public land: 137,024,000 acres (federal vast mixed- and short-grass prairies. To protected by the National Wildlife and state) the west rise the Rocky Mountains and Refuge System (NWRS), including ■ Wildlife-dependent recreation: the intermountain areas beyond the both fee title and easement lands. This 7,275,000 people* (hunting, fishing, and Continental Divide, including parts of includes 124 national wildlife refuges, wildlife watching) the sprawling Colorado Plateau and the 18 coordination areas, and numerous * USDA Economic Research Service Great Basin. The northeastern part of waterfowl production areas in 120 **FY 2011 National Survey of Fishing, the Region contains millions of shallow counties through Fiscal Year 2012. Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated wetlands known as the “prairie ■ 2,576,476 visitors to NWRS lands in Recreation potholes,” which produce a large portion Fiscal Year 2012. -

Great Plains. in Respiration and Increase in Net Primary Productivity Due Source: Adapted from Anderson (1995) and Schaefer and Ball (1995)

Great Plains Gary Bentrup and Michele Schoeneberger Gary Bentrup is a research landscape planner, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service, USDA National Agroforestry Center; Michele Schoeneberger is research program lead and soil scientist (retired), USDA Forest Service, USDA National Agroforestry Center. Description of the Region generates a total market value of about $92 billion, approx- imately equally split between crop and livestock production Extending from Mexico to Canada, the Great Plains Region (USDA ERS 2012). Agricultural activities range in the northern covers the central midsection of the United States and is Plains from crop production, dominated by alfalfa, barley, corn, divided into the northern Plains (Montana, Nebraska, North hay, soybeans, and wheat to livestock production centered on Dakota, South Dakota and Wyoming) and the southern Plains beef cattle along with some dairy cows, hogs, and sheep. In (Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas). This large latitudinal range the southern Plains, crop production is centered predominantly leads to some of the coldest and hottest average temperatures in on wheat along with corn and cotton, and extensive livestock the conterminous United States and also to a sharp precipitation production is centered on pastureland or rangelands and inten- gradient from east to west (fig. A.6). The region also experi- sive production in feedlots. Crop production is a mixture of 82 ences multiple climate and weather hazards, including floods, percent dryland and 18 percent irrigated cropland, with 34 and droughts, severe thunderstorms, rapid temperature fluctuations, 31 percent of total irrigated cropland in the region occurring in tornadoes, winter storms, and even hurricanes in the far Nebraska and Texas, respectively (USDA NRCS 2013).