Discover Lewis and Clark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Biological Assessment

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION .................................................................................................................... 1 3 PROPOSED ACTION ................................................................................................................................. 2 3.1 Project Area ............................................................................................................................... 2 3.2 Proposed Action ........................................................................................................................ 4 3.2.1 Current Permit ....................................................................................................................... 4 3.2.2 Grazing System ..................................................................................................................... 4 3.2.3 Conservation Measures ........................................................................................................ 5 3.2.4 Changes From Existing Management ................................................................................... 5 3.2.5 Resource Objectives and Standards .................................................................................... 6 3.2.6 Annual Grazing Use indicators .............................................................................................. 7 -

Lookbook a CAT CALLED SAM & a DOG NAMED DUKE

AW21 A CAT CALLED SAM & A DOG NAMED DUKE click here to VIEW OUR Lookbook VIDEO thebonniemob.com AW21 AW21 S STAINABLE A CAT CALLED SAM & RECYCLE ORG NIC A DOG NAMED DUKE This is the story of a cat called Sam and a dog named Duke. Everyone said that they couldn’t be friends, because cats and dogs aren’t allowed to like each other!!! But Sam and Duke were different, they were the best of friends and loved each other very much, they liked to hang out together with their owner, a famous artist called Andy Warhol. They threw parties for all the coolest cats and dogs of New York, where they would dance the night away looking up at the city skyline, when they spotted a shooting star they’d make wishes for a world filled with art and colour and fun and kindness.......... click here click here click here to for to VIEW COLLECTION VIEW OUR INSPIRATION runthrough VIDEO Video Video CULTURE T shirt click click here CAMPBELL here for Hareem pants to order line sheets online CANDY dress THUMPER #welovebonniemob tights 2 3 thebonniemob.com AW21 LIZ A Hat G NI R C LIBERTY O ABOUT US Playsuit C LEGEND We are The bonnie mob, a multi-award winning sustainable baby and O N childrenswear brand, we are a family business, based in Brighton, on the sunny T T O Blanket South Coast of England. We are committed to doing things differently, there are no differences between what we want for our family and what we ask from our brand. -

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's Truman Capote, 1958 I Am Always Drawn Back To

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's surrounded by photographs of ice-hockey stars, there is always a large bowl of fresh Truman Capote, 1958 flowers that Joe Bell himself arranges with matronly care. That is what he was doing when I came in. I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their "Naturally," he said, rooting a gladiola deep into the bowl, "naturally I wouldn't have neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, got you over here if it wasn't I wanted your opinion. It's peculiar. A very peculiar thing during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room has happened." crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red "You heard from Holly?" velvet that one associates with hot days on a tram. The walls were stucco, and a color He fingered a leaf, as though uncertain of how to answer. A small man with a fine rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman head of coarse white hair, he has a bony, sloping face better suited to someone far ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, taller; his complexion seems permanently sunburned: now it grew even redder. "I can't my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its say exactly heard from her. I mean, I don't know. -

History of the Blanket Capote in North America

Volume 23, No. 2 February 2018 EARLYShinnin’ ARKANSAW REENA CTORS Times ASSOCIATION Save The Date History of the Blanket Capote in March 2-4—White Oak State Park Colonial North America Event, Ed Williams 501- The capote, or long greatcoat, has long been closely associated with 944-0736 or the fur trade in North America. It is not surprising that the wide-scale [email protected] harvesting of furs for European markets coincided with the development March 10-18 Southwest of this uniquely Canadian garment. Indeed the capotes, or more specifi- Regional Rendezvous— cally the wool blankets from which they were sewn, became one of the Nacona, TX most sought after trade items, replacing furs as the typical winter cloth- ing for both the native and European trappers and traders alike. April 6-8 Sulpher Fork Days Origins of the Capote Doddridge, AR Con- The capote came to be associated with the Hudson’s Bay Company tact Sam Bumgardner and is sometimes referred to as the “Hudson’s Bay coat.” But it is also 903-824-3105 more generally associated with the French habitants and voyageurs, as it originated in New France. The term “capot” or “capote” comes from April 14-15 - Colbert's the French word for cloak. “Capote” is a term used in North America since the early 1600s when French sailors were trading their coats with Raid at Arkansas the Micmac on the Atlantic coast. Pierre Radisson (1636-1701) men- Post. All come to cel- tions wearing a “cappot” or “capot” in his autobiographical journal long ebrate the last battle before any Hudson’s Bay Company records mention such an item. -

Lemhi County, Idaho

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BUIJLETIN 528 GEOLOGY AND ORE DEPOSITS 1 OF LEMHI COUNTY, IDAHO BY JOSEPH B. UMPLEBY WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1913 CONTENTS. Page. Outline of report.......................................................... 11 Introduction.............................................................. 15 Scope of report......................................................... 15 Field work and acknowledgments...................................... 15 Early work............................................................ 16 Geography. .........> ....................................................... 17 Situation and access.........................--.-----------.-..--...-.. 17 Climate, vegetation, and animal life....................----.-----.....- 19 Mining................................................................ 20 General conditions.......... 1..................................... 20 History..............................-..............-..........:... 20 Production.................................,.........'.............. 21 Physiography.............................................................. 22 Existing topography.................................................... 22 Physiographic development............................................. 23 General features...............................................'.... 23 Erosion surface.................................................... 25 Correlation............. 1.......................................... -

Driving Truman Capote: a Memoir

Theron Montgomery Driving Truman Capote: A Memoir On a calm, cool April afternoon in 1975, I received an unexpected call from my father on the residence First Floor pay phone in New Men’s Dorm at Birmingham-Southern College. My father’s voice came over the line, loud and enthused. “Hi,” he said, enjoying his surprise. He asked me how I was doing, how school was. “Now, are you listen- ing?” he said. “I’ve got some news.” Truman Capote, the famous writer of In Cold Blood, would be in our hometown of Jacksonville, Alabama, the next day to speak and read and visit on the Jacksonville State University campus, where my father was Vice-President for Academic Affairs. It was a sudden arrangement Capote’s agent had negotiated a few days before with the school, pri- marily at my father’s insistence, to follow the author’s read- ing performance at the Von Braun Center, the newly dedicat- ed arts center, in Huntsville. Jacksonville State University had agreed to Capote’s price and terms. He and a traveling companion would be driven from Huntsville to the campus by the SGA President early the next morning and they would be given rooms and breakfast at the university’s International House. Afterwards, Capote would hold a luncheon reception with faculty at the library, and in the afternoon, he would give a reading performance at the coliseum. My father and I loved literature, especially southern liter- ature, and my father knew I had aspirations of becoming a writer, too. “You must come and hear him,” he said over the phone, matter-of-fact and encouraging. -

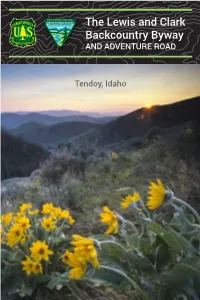

Idaho: Lewis Clark Byway Guide.Pdf

The Lewis and Clark Backcountry Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho Meriwether Lewis’s journal entry on August 18, 1805 —American Philosophical Society The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road is a 36 mile loop drive through a beautiful and historic landscape on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. The mountains, evergreen forests, high desert canyons, and grassy foothills look much the same today as when the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through in 1805. THE PUBLIC LANDS CENTER Salmon-Challis National Forest and BLM Salmon Field Office 1206 S. Challis Street / Salmon, ID 83467 / (208)756-5400 BLM/ID/GI-15/006+1220 Getting There The portal to the Byway is Tendoy, Idaho, which is nineteen miles south of Salmon on Idaho Highway 28. From Montana, exit from I-15 at Clark Canyon Reservoir south of Dillon onto Montana Highway 324. Drive west past Grant to an intersection at the Shoshone Ridge Overlook. If you’re pulling a trailer or driving an RV with a passenger vehicle in tow, it would be a good idea to leave your trailer or RV at the overlook, which has plenty of parking, a vault toilet, and interpretive signs. Travel road 3909 west 12 miles to Lemhi Pass. Please respect private property along the road and obey posted speed signs. Salmon, Idaho, and Dillon, Montana, are full- service communities. Limited services are available in Tendoy, Lemhi, and Leadore, Idaho and Grant, Montana. -

BPA Partners with Idaho to Secure More Than 4600 Acres to Benefit Fish

BONNEVILLE POWER ADMINISTRATION Fact Sheet July 2015 BPA partners with Idaho to secure more than 4,600 acres to benefit fish Habitat conservation – PURPOSE: The Bonneville Power Administration is partially funding the purchase of a conservation public notice easement that would permanently protect nearly DATE: July 2015 10 miles of in-stream and riparian habitat near the town of Leadore in Lemhi County, Idaho. LOCATION: Leadore, Lemhi County, Idaho (see map on page 4) This acquisition will partially mitigate the impacts to salmon and steelhead from the construction, ACRES: 4,682 (nearly 10 miles of in-stream and inundation and continued operation of federal riparian habitat along the mainstem of the Lemhi River) hydroelectric dams in the Columbia River and Snake © ILONA MCCARTY OPEN VIEW PHOTOGRAPHY the elimination of a ditch on the Lemhi River and participation in a 72-hour high flow event during which water withdrawals will be curtailed to mimic or enhance channel forming and maintaining events. When combined with similar efforts on neighboring conservation easements on the Lemhi River, these actions will result in 100 cubic feet per second flowing through more than 25 miles of main river and tributary habitat. These flushing flows will help increase egg and smolt survival over time as gravels are consistently washed clean for successive brood years. SPECIES BENEFITED: Snake River spring/summer Headwaters of the Lemhi River at the confluence of Texas and chinook, steelhead Eighteen Mile creeks. Leadore Land Partners Ranch, 2012 TYPES OF LAND: In-stream and riparian River basins. The conservation of habitat is one TYPE OF ACTION: BPA is working with the Idaho component of a broader, comprehensive strategy to Office of Species Conservation and the Lemhi Regional improve conditions for fish at all stages of their life in Land Trust to negotiate a conservation easement on the river. -

Rich, Attractive People in Attractive Places Doing Attractive Things Tonya Walker Virginia Commonwealth University

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Rich, Attractive People In Attractive Places Doing Attractive Things Tonya Walker Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/992 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rich, Attractive People Doing Attractive Things in Attractive Places - A Monologue from Hell - - by Tonya Walker, Master of Fine Arts Candidate Major Director: Tom De Haven, Professor, Department of English Acknowledgement This thesis could not have been completed - completed in the loosest sense of the word - had in not been for the time and involvement of three men. I'd like to thank my mentor David Robbins for his unfailing and passionate disregard of my failings as a writer, my thesis director Tom De Haven for his patient support and stellar suggestions that are easily the best in the book and my husband Philip whose passionate disregard of my failings and patient support are simply the best. Abstract RICH, ATTRACTIVE PEOPLE IN ATTRACTIVE PLACES DOING ATTRACTIVE THINGS By Tonya Walker, M.F.A. A these submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 Major Director: Tom De Haven, Professor, Department of English Rich, Attractive People in Attractive Places Doing Attractive Things is a fictional memoir of a dead Manhattan socialite from the 1950's named Sunny Marcus. -

The Voyageur

RADIOGRAMS OF MINNESOTA HISTORY THE VOYAGEUR1 Every section of the United States is rapidly becoming inter ested in the folklore peculiar to itself. This condition is an evidence that the nation has passed the hurry of its youth and, settling into maturity, is now looking back with tender affection on the scenes of its childhood. The Indian is no longer a pest to be exterminated as speedily as possible, though our pioneer ing ancestors regarded him as such. He had habits, traditions, and customs that make him worthy of study by every section of the country. In similar fashion, the South is finding more than a beast of burden in the Negro, whose "spirituals" and tales are taking a high place in the folklore of the world. Thus far we in the Upper Mississippi Valley have overlooked, in large measure, the outstanding figure among our makers of folklore, if we except the Indian. Like much of the northern part of the United States and practically all of Canada, we have the voyageur, one of the most colorful figures in the his tory of the continent. We might translate the name and call him a canoeman, but he would never recognize himself in the new word, for he spoke no English; and those peculiar impressions which the very utterance of the French term call to mind would be lost if we were to call him by any other name than that by which he designated himself. Yankees and Scotchmen could be canoemen, and sometimes were; only French-Canadians could be voyageurs. -

Salmon River Drainage

Volume 059 Article 08 STATE OF IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME 518 Front Street Boise, Idaho April 2, 1959 Recipients of this report: The attached report, prepared by Stacy Gebhards, contains a summary of information collected by him and other Department workers and constitutes the initial phase of the preparation of a planning report on the entire Salmon River drainage. Before the report is completed for the entire drainage, many persons will contribute additional information which will be inserted as it becomes available. The attached should be used as a guide in preparing reports on future survey work. LWM:cjc encl. COLUMBIA RIVER FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Preliminary Planning Report SALMON RIVER by Stacy V. Gebhards STATE OF IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Salmon, Idaho January 6, 1959 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction .................................................... 1 Little Salmon River.......... 1 ................................. 2 South Fork of the Salmon River .................................. 5 Secesh River and Lake Creek ................................ 7 East Fork of the South Fork ................................ 7 Johnson Creek .............................................. 8 Cabin Creek ................................................ 9 Warm Lake Creek ............................................ 9 Middle Fork of the Salmon River ................................ 13 Big Creek ................................................. 14 Wilson Creek .............................................. 15 Camas Creek ..............................................