Sargon of Agade and His Successors in Anatolia *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mesopotamia Timeline

Mesopotamia Timeline 5000 BC - The Sumer form the first towns and cities. They use irrigation to farm large areas of land. 4000 BC - The Sumer establish powerful city-states building large ziggurats at the center of their cities as temples to their gods. 3500 BC - Much of lower Mesopotamia is inhabited by numerous Sumer city-states such as Ur, Uruk, Eridu, Kish, Lagash, and Nippur. 3300 BC - The Sumerians invent the first writing. They use pictures for words and inscribe them on clay tablets. 3200 BC - The Sumerians begin to use the wheel on vehicles. 3000 BC - The Sumerians start to implement mathematics using a number system with the base 60. 2700 BC - The famous Sumerian King Gilgamesh rules the city-state of Ur. 2400 BC - The Sumerian language is replaced by the Akkadian language as the primary spoken language in Mesopotamia. 2330 BC - Sargon I of the Akkadians conquers most of the Sumerian city states and creates the world's first empire, the Akkadian Empire. 2250 BC - King Naram-Sin of the Akkadians expands the empire to its largest state. He will rule for 50 years. 2100 BC - After the Akkadian Empire crumbles, the Sumerians once again gain power. The city of Ur is rebuilt. 1900 BC - The Assyrians rise to power in northern Mesopotamia. 1792 BC - Hammurabi becomes king of Babylon. He establishes the Code of Hammurabi and Babylon soon takes over much of Mesopotamia. 1781 BC - King Shamshi-Adad of the Assyrians dies. The First Assyrian Empire is soon taken over by the Babylonians. 1750 BC - Hammurabi dies and the First Babylonian Empire begins to fall apart. -

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

Mesopotamian Epic."

' / Prof. Scott B. Noege1 Chair, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization University of Washington "Mesopotamian Epic." First Published in: John Miles Foley, ed. The Blackwell Companion to Ancient Epic London: Blackwell (2005), 233-245. ' / \.-/ A COMPANION TO ANCIENT EPIC Edited by John Miles Foley ~ A Blackwell '-II Publishing ~"o< - -_u - - ------ @ 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right ofJohn Miles Foley to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2005 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to ancient epic / edited by John Miles Foley. p. cm. - (Blackwell companions to the ancient world. Literature and culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-4051-0524-0 (alk. paper) 1. Epic poetry-History and criticism. 2. Epic literature-History and criticism. 3. Epic poetry, Classical-History and criticism. I. Foley, John Miles. II. Series. PN1317.C662005 809.1'32-dc22 2004018322 ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-0524-8 (hardback) A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. -

STUDIA BIBLIJNE Słowa Kluczowe: Stary Testament, Druga Księga Królewska, Asyria, Samaria, Izrael, Nergal, Nergal Z Cuta

2 STUDIA BIBLIJNE Słowa kluczowe: Stary Testament, Druga Księga Królewska, Asyria, Samaria, Izrael, Nergal, Nergal z Cuta 82 Keywords: The Old Testament, 2 Kings, Asyria, Samaria, Israel, Nergal, Nergal of Cuth Ks. Leszek Rasztawicki Warszawskie Studia Teologiczne DOI: 10.30439/WST.2019.4.5 XXXII/4/2019, 82-104 Ks. Leszek Rasztawicki PAPIESKI WYDZIAł TEOLOGICZNY W WARSZAWIE COLLEGIUM JOANNEUM ORCID: 0000-0002-5140-0819 „ THE PEOPLE OF CUTH MADE NERGAL” (2 KINGS 17:30). THE HISTORICITY AND CULT OF NERGAL IN THE ANCIENT MIDDLE EAST. The deity Nergal of Cuth appears only once in the Hebrew Bible (2 Kings 17:30). He is mentioned among a list of some Assyrian gods, which new repopulated settlers in Samaria “made” for themselves after the fall of the Northern Kingdom. In this brief paper, we would like to investigate the historicity of Nergal of Cuth in the context of Mesopotamian literature and religion. REPOPULATION OF SAMARIA The Assyrians after conquering a new territory relocated people from other regions of the empire to newly subjugated provinces (2 Kings 17:24). The people of 83 „ THE PEOPLE OF CUTH MADE NERGAL” (2 KINGS 17:30) Samaria were carried away into exile (2 Kings 17:6, 18:11). The repopulation policy of the Assyrians is well documented from their own records1. Sargon II (722-705 BC) took credit in Assyrian royal inscriptions for deporting 27,290 inhabitants of Sa- maria (Sargon II prism IV:31)2: ... he defeated and conquered Samaria, and carried away as slaves 27290 inhabitants ... he rebuilt the city better than before and settled in it people of other countries .. -

2-3-1: the First Empire Builders: Objective: Students Will Trace the Development of the First Empires in Mesopotamia, Akkad and Babylon

CHAPTER 2 Section 3: Empire of the Fertile Crescent 2-3-1: The First Empire Builders: Objective: Students will trace the development of the first empires in Mesopotamia, Akkad and Babylon. Introduction 1. Who fought for control of Mesopotamia from 3000 B.C. to 2000 B.C.? *Kings from different city-states. a. What factor allowed for such invasions? *The land was flat and easy to invade. b. What would one gain from controlling the region? *More land (more land means more wealth and power). 2. Despite the many efforts, how many rulers were able to control ALL of Mesopotamia? *None there were always some parts of Mesopotamia that were independent of the empire and could not be overtaken (its hard in ancient times to control large areaswe will see these struggles throughout the year). The Akkadian Empire: 3. Which ruler took control of Mesopotamia in 2371 B.C.? *Sargon (I) of Akkad a. What was this ruler known as? *Creator of the world’s first empire. How was he able to do this (Hint: think about the definition to # 4/5, the answer is not in your book)? *He conquered the many (12+) city-states of Sumer. 4. Define empire : *group of territories and peoples brought together under one supreme ruler (in this case the Sumerians under the rule of the Akkadians). 5. Define emperor : Person who rules an empire (Sargon I of Akkad) 6. Sargon’s empire was known as the ___ Empire. *Akkadian Empire 7. Define Fertile Crescent : *region stretching from the Persian Gulf through Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean Sea a. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transit Corridors And

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transit Corridors and Assyrian Strategy: Case Studies from the 8th-7th Century BCE Southern Levant A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philisophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Heidi Michelle Fessler 2016 © Copyright by Heidi Michelle Fessler 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transit Corridors and Assyrian Strategy: Case Studies from the 8th-7th Century BCE Southern Levant by Heidi Michelle Fessler Doctor of Philisophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Aaron Alexander Burke, Chair Several modern studies and the Assyrians themselves have claimed not only the extreme military measures but also substantial geo-political impact of Assyrian conquest in the southern Levant; however, examples of Assyrian violence and control are actually underrepresented in the archaeological record. The few scholars that have pointed out this dearth of corroborative data have attributed it to an apathetic attitude adopted by Assyria toward the region during both conquest and political control. I argue in this dissertation that the archaeological record reflects Assyrian military strategy rather than indifference. Data from three case studies, Megiddo, Ashdod, and the Western Negev, suggest that the small number of sites with evidence of destruction and even fewer sites with evidence of Assyrian imperial control are a product of a strategy that allowed Assyria to annex the region with less investment than their annals claim. ii Furthermore, Assyria’s network of imperial outposts monitored international highways in a manner that allowed a small local and foreign population to participate in trade and defense opportunities that ultimately benefited the Assyrian core. -

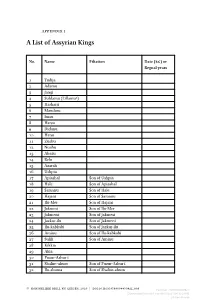

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

A History of Ancient Egypt, 2Nd Edition Marc Van De Mieroop

To purchase this product, please visit https://www.wiley.com/en-us/9781119620877 A History of Ancient Egypt, 2nd Edition Marc Van De Mieroop E-Book 978-1-119-62089-1 January 2021 $40.00 Paperback 978-1-119-62087-7 January 2021 $50.00 DESCRIPTION Explore the entire history of the ancient Egyptian state from 3000 B.C. to 400 A.D. with this authoritative volume The newly revised Second Edition of A History of Ancient Egypt delivers an up-to-date survey of ancient Egypt's history from its origins to the Roman Empire's banning of hieroglyphics in the fourth century A.D. The book covers developments in all aspects of Egypt's history and their historical sources, considering the social and economic life and the rich culture of ancient Egypt. Freshly updated to take into account recent discoveries, the book makes the latest scholarship accessible to a wide audience, including introductory undergraduate students. A History of Ancient Egypt outlines major political and cultural events and places Egypt's history within its regional context and detailing interactions with western Asia and Africa. Each period of history receives equal attention and a discussion of the problems scholars face in its study. The book offers a foundation for all students interested in Egyptian culture by providing coverage of topics like: • A thorough introduction to the formation of the Egyptian state between the years of 3400 B.C. and 2686 B.C. • An exploration of the end of the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate period, from 2345 B.C. to 2055 B.C. -

Sargon of Akkade and His God

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 69 (1), 63–82 (2016) DOI: 10.1556/062.2016.69.1.4 SARGON OF AKKADE AND HIS GOD COMMENTS ON THE WORSHIP OF THE GOD OF THE FATHER AMONG THE ANCIENT SEMITES STEFAN NOWICKI Institute of Classical, Mediterranean and Oriental Studies, University of Wrocław ul. Szewska 49, 50-139 Wrocław, Poland e-mail: [email protected] The expression “god of the father(s)” is mentioned in textual sources from the whole area of the Fertile Crescent, between the third and first millennium B.C. The god of the fathers – aside from assumptions of the tutelary deity as a god of ancestors or a god who is a deified ancestor – was situated in the centre and the very core of religious life among all peoples that lived in the ancient Near East. This paper is focused on the importance of the cult of Ilaba in the royal families of the ancient Near East. It also investigates the possible source and route of spreading of the cult of Ilaba, which could have been created in southern Mesopotamia, then brought to other areas. Hypotheti- cally, it might have come to the Near East from the upper Euphrates. Key words: religion, Ilaba, royal inscriptions, Sargon of Akkade, god of the father, tutelary deity, personal god. The main aim of this study is to trace and describe the worship of a “god of the fa- ther”, known in Akkadian sources under the name of Ilaba, and his place in the reli- gious life of the ancient peoples belonging to the Semitic cultural circle. -

Decoding the Medinet Habu Inscriptions: the Ideological Subtext of Ramesses III’S War Accounts

Peters 1 Decoding the Medinet Habu Inscriptions: The Ideological Subtext of Ramesses III’s War Accounts Abstract: The temple of Medinet Habu in Thebes stands as Ramesses III‘s lasting legacy to Ancient Egyptian history. This monumental structure not only contained luxury goods within, but also a goldmine of information inscribed on its outside walls. Here, Ramesses adorned the temple with stories of military campaigns he led against enemies in the north who hoped to gain control of Egypt. These war accounts have posed a series of problems to modern scholars. Today, the debate still rages over how the inscriptions should be interpreted. This work analyzes Ramesses‘s records through the lens of socioeconomic decline that occurred during his rule in order to demonstrate the role ideology—namely ma‘at—played in his self-representation and his methodology to ensure and legitimize his rule during these precarious times. Scott M. Peters Senior Thesis, Department of History Columbia College, Columbia University April 2011 Advisors: Professor Marc Van De Mieroop and Professor Martha Howell Word Count: 17,070 (with footnotes + bibliography included) Peters 2 Figure 1: Map of Ancient Egypt with key sites. Image reproduced from Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of Ancient Egypt (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 28. Peters 3 Introduction When describing his victory over invading forces in the north of Egypt, Ramesses III, ruler at the time, wrote: …Those who came on land were overthrown and slaughtered…Amon-Re was after them destroying them. Those who entered the river mouths were like birds ensnared in the net…their leaders were carried off and slain. -

KARUS on the FRONTIERS of the NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo

KARUS ON THE FRONTIERS OF THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE I Shigeo YAMADA * The paper discusses the evidence for the harbors, trading posts, and/or administrative centers called karu in Neo-Assyrian documentary sources, especially those constructed on the frontiers of the Assyrian empire during the ninth to seventh centuries Be. New Assyrian cities on the frontiers were often given names that stress the glory and strength of Assyrian kings and gods. Kar-X, i.e., "Quay of X" (X = a royal/divine name), is one of the main types. Names of this sort, given to cities of administrative significance, were probably chosen to show that the Assyrians were ready to enhance the local economy. An exhaustive examination of the evidence relating to cities named Kar-X and those called karu or bit-kar; on the western frontiers illustrates the advance of Assyrian colonization and trade control, which eventually spread over the entire region of the eastern Mediterranean. The Assyrian kiirus on the frontiers served to secure local trading activities according to agreements between the Assyrian king and local rulers and traders, while representing first and foremost the interest of the former party. The official in charge of the kiiru(s), the rab-kari, appears to have worked as a royal deputy, directly responsible for the revenue of the royal house from two main sources: (1) taxes imposed on merchandise and merchants passing through the trade center(s) under his control, and (2) tribute exacted from countries of vassal status. He thus played a significant role in Assyrian exploitation of economic resources from areas beyond the jurisdiction of the Assyrian provincial government. -

Cambridge Histories Online

Cambridge Histories Online http://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/histories/ The Cambridge World Prehistory Edited by Colin Renfrew, Paul Bahn Book DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139017831 Online ISBN: 9781139017831 Hardback ISBN: 9780521119931 Chapter 3.10 - Anatolia from 2000 to 550 bce pp. 1545-1570 Chapter DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139017831.095 Cambridge University Press 3.10 ANATOLIA FROM 2000 TO 550 BCE ASLI ÖZYAR millennium, develops steadily from an initial social hierarchy, The Middle Bronze as is manifest in the cemeteries and settlement patterns of Age (2000–1650 BCE) the 3rd millennium BCE, towards increased political complex- ity. Almost all sites of the 2nd millennium BCE developed on Introduction already existing 3rd-millennium precursors. Settlement con- tinuity with marked vertical stratification is characteristic for the inland Anatolian landscape, leading to high-mound for- Traditionally, the term Middle Bronze Age (MBA) is applied to mations especially due to the use of mud brick as the preferred the rise and fall of Anatolian city-states during the first three building material. Settlement continuity may be explained in centuries of the 2nd millennium BCE, designating a period last- terms of access to water sources, agricultural potential and/or ing one-fifth of the timespan allotted to the early part of the hereditary rights to land as property mostly hindering horizon- Bronze Age. This is an indication of the speed of developments tal stratigraphy. An additional or alternative explanation can be that led to changes in social organisation when compared to the continuity of cult buildings, envisaged as the home of dei- earlier millennia.